doc - The Industrial Heritage Association of Ireland

advertisement

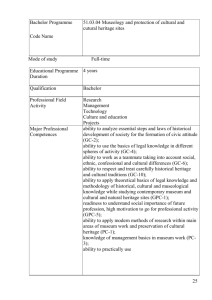

INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE NETWORKING SOME OBSERVATIONS At the gathering organised by the Industrial Heritage Association and the Heritage Council in Dublin Castle on 15th November 2006 several important subjects were discussed. Transport Museum Society of Ireland (TMSI) personnel have encountered many of the obstacles described by participants and we would hope that knowledge of how we tried to deal with innumerable obstacles might contribute to solving some of the problems encountered by others. Culture, mentioned by a number of speakers, is one that we have persistently tried to cope with since 1949 when we were told by the National Museum that the preservation of a tramcar would not be in accordance with the national ethos (and still isn’t). This theme can be explained by an expansion of the theme alluded to by one contributor. Despite the presence of mills and engineering related directly to agriculture, the Industrial Revolution bypassed most of Ireland, our economy and culture remaining predominantly rural for aeons. The technology, skills and conventions associated with heavy industry and mechanical transport were outside the pale of rural awareness. They were also beyond urban cultural acceptability, which saw all such activity as the domain of artisans and the lower orders – the general service classes. Modern Irish culture, a merger of rural and urban values, perpetuates these old prejudices. It is a deficient fusion, in which education favours the arts and humanities. Politics, and the civil and public services are, with rare exceptions, dominated by people from this narrow background, as are the media. Their attitudes to engineering and transport are typically tangential, their knowledge of technical history, traditions and heritage minimal; and what they do not understand, they reject and frequently denigrate. Until now, we feared that this official cultural mindset that barely understands the pivotal importance of engineering and technology might take at least another generation to realise that it also rich in history and heritage. However, the appointment of local authority Heritage Officers gives some hope that Irish culture may at last embrace those involved in preserving our technological heritage. Inculcating pride in the past and inspiration for the future, archaic machinery and vehicles honour the lives and achievements of every individual whose ingenuity, labour and sacrifices have contributed to social and economic progress. They also exhibit mastery in design and craftsmanship that fascinates people from every background. Fostering goodwill, promoting education and generating tourism, heritage collections are a source of pride in progressive civilisations whose culture seamlessly embraces every aspect of human accomplishment. Visitors from those inclusive civilisations who expect to find technical museums in Ireland face disappointment. While students, researchers and professionals visit museums regularly, curiosity and nostalgia drive the majority of callers. To cater for the average visitor, the Transport Museum has reduced the technical content in its information panels in favour of more social history. An example is attached. Outside the scope and scholarship of conventional museums, large engineering artefacts are especially difficult to preserve and display. Information about their deployment and skills based on practical experience in both engineering and museum disciplines are essential for the assembly, restoration and management of representative collections, and specialised knowledge is required to site them in correct contexts. The Heritage Council recognised all of this when it invited the TMSI to participate in its Museum Accreditation Pilot Programme. The Society gratefully acknowledges the recognition and support of the Council and will be happy to share any expertise it has acquired with others. Several years ago, TMSI members recognised the need to plan for what should be preserved and the result was the compilation, in 1974, of a list of vehicles to be targeted over the following ten years. This list has been regularly updated ever since and has ensured the retention of more than 150 historic vehicles. While not consciously formalised at the time, the criteria for selection were instinctively based on the principles used by architects and planners when listing historic buildings. Architects and planners investigate how structures being considered for preservation meet eight criteria: (1) Architectural; (2) Historical; (3) Archaeological: (4) Artistic; (5) Cultural; (6) Scientific; (7) Social, and (8) Technical. In 2002, these criteria were reinforced when “Recording and Conserving Ireland’s Industrial Heritage” listed the following intrinsic qualities of industrial conservation sites: (1) Aesthetic; (2) Physical; (3) Historic; (4) Technical and Scientific; (5) Social; (6) Age and Rarity, and (7) Setting. During the 1980s, TMSI members discovered that there was no national plan to cater for items outside the limited remit of the National Museum and the Office of Public Works. Realising that much broader considerations were needed to govern heritage and preservation generally, TMSI members in 1987 drafted a Code of Preservation Principles. These have since been updated and modified in the light of practical experience and detailed examination during the Society’s participation in the museum accreditation programme. Although they were drawn up with transport preservation primarily in mind, the code can be adapted, with appropriate modifications, to most other spheres of conservation. They are as follows: 1. Our heritage is not confined to any particular activity, period or culture in our land. It is all our past, to be preserved, again, in our land. 2. A thoroughly researched, comprehensive and widely publicised national policy is essential, regularly and empirically updated. 3. Knowledge and ability to promote preservation impose a social obligation to do so. Every attendant action and procedure must be legal, ethical, positive and realistic. Every procedure and programme must also be inclusive and transparent. 4. No individual or organisation has a monopoly of knowledge on any subject, consensus being the ideal lodestar of every project. Organisations and individuals must be accountable for their decisions and actions. 5. The preservation process must be continuous, today’s utilitarian objects being to-morrow’s museum pieces. Overpreservation is preferable to subduction. 6. Selection of artefacts should be timely and comprehensive, recognising progression from obsolescence to antique status. 7. Special attention must be given to recently obsolete and redundant artefacts, which exist at highest risk in a twilight zone. 8. Projects must always be related to social, economic and technological restraints, respecting the viewpoints, qualifications and rights of others. 9. Organisations and structures should be geared to the needs of particular projects and be readily adaptable to changing circumstances. Management and key personnel must be technically qualified, competent, committed, experienced and disciplined. 10. Conservation, restoration and overhaul should conform to correct operational practices, taking cognisance of all contemporary circumstances. 11. There should be maximum co-ordination and exchange of information between preservation organisations, with rapid and effective emergency procedures. 12. Adequate and equitably distributed finance from public funds and commercial sources is vital to preservation. 13. All funding must be directed exclusively to the purposes for which it is untended, with strict financial supervision to preclude waste and uncontrolled over-runs. 14. Stakeholders, suppliers and financiers of new equipment should be encouraged to support the preservation of historic artefacts made redundant by what they supply or from the preservation of which they benefit. 15. Heritage collections should include constantly expanding archives and comprehensive records, regularly updated, of conservation projects. 16. As the rate of change accelerates, preservation urgencies multiply. Increasing leisure time should be channelled into enhancing and expanding what we hold in trust for future generations. 17. Our every action should recognise that we are merely ephemeral custodians of a heritage, the extent and condition of which will be judged by posterity, to whom we are ultimately responsible. Several of the subjects debated on 15th November are covered in the code, e.g. funding, exchange of information and archives. This writer got a strong impression that archives is a matter requiring considerable attention. Members of the TMSI are involved, both in their employment and while working for the museum, in the collection, cataloguing and safeguarding of archival material. These items include drawings, photographs, sales literature, catalogues, workshop manuals, timetables, tickets etc. and any experience gained will be gladly passed on. We have been particularly lucky in having the advice of the City Archivist and Library staff. Several individuals hold personal archival collections which ideally, on the demise of their owners, should pass into the care of people qualified to look after them. Another subject broached was the high profile enjoyed by the arts as opposed to technology. There is a widespread impression that the arts merit support but the technology that finances them does not. This is particularly so in Ireland, where science is subservient to the humanities and the artisan is inferior to the artist. Many engineering companies and public utility providers making huge profits support the arts but ignore the history and heritage of their own industry. Progress in changing this imbalance here might lie in enlisting the help of technical and science journalists. Meanwhile, we know from long experience that visitors react positively to what we display, express their appreciation, ask many questions and frequently return with family members and friends. People working on projects regularly consult TMSI personnel. We always try to help but, time and again, are staggered by the total ignorance of transport, modern or historic, displayed by the enquirers. They range through archaeologists, historians, journalists, film makers, sociologists, architects and community or public officials. Their lack of knowledge is no reflection on these people, most of them highly educated but victims of the massive cultural deficit in a society placing total emphasis on the humanities to the absolute exclusion of technology, its disciplines, culture, history or heritage. So complete is the innocence encountered that we frequently have to bring enquirers back several steps from the more advanced aspects they ask about to give them the most fundamental facts about transport. Similar remarks probably apply to industrial equipment. Now that various authorities are beginning to discover the diversity of our heritage, each newfound area’s educational and tourism potential will be exploited. There is, unfortunately, every likelihood of serious mistakes being made when the authorities – State, semi-State or local – become involved. These will probably in selection, conservation and management: critical areas requiring fast, positive, sensitive action by knowledgeable, highly motivated specialists. Eventually, full-time staff will have to replace the part-time voluntary custodians of our technological heritage. But there is absolutely no hope that a few half-day seminars will prepare existing museum personnel who survive the initial culture shock for work in this physically tough, highly specialised field. So, what is the ideal background – technical people with archaeological training – or museum personnel who have completed an engineering course? In the UK, some arbitrary and insensitive appointments to key posts of people with the wrong qualifications and attitude have caused serious concern: and we must surely learn from this. Members of specialist societies have built up unique expertise and it is important that what they have learned becomes part of the basis for education in technological heritage studies. As a growing number of collections in the State will probably, in time, require professional management, there is a need to establish what training should be provided for entrants to this discipline, culminating in a distinctive specialist qualification. For example, any course for transport museum people would, first of all, have to include studies in both modern and historic transport in its four manifestations: water, air, rail and road. Anybody put in charge of an industrial museum would need to be versed in the appropriate subjects. Basics include a thorough knowledge of how the engineering industry, operating and manufacturing, evolved. Social history must be researched to ensure that collections are placed in its correct context. Knowledge of current engineering theory and practice is also essential because out of this springs the ability to pre-select future museum pieces. Another essential is to know the logistics and equipment necessary for the timely securing, uplifting, transport, housing, overhaul and restoration of exhibits. While we are in a position to help in educating future museum personnel we are also conscious both of our own limitations and the need for specialists in other disciplines. The TMSI was the only museum with an engineering background to participate in the Heritage Council’s Accreditation Programme. We learned much from this and will be happy to pass on anything our colleagues in other organisations might like to have. Finally, co-operation and networking, the theme of last week’s gathering, would be most beneficial. Hoping that these notes may be of some interest. ____________________ Michael Corcoran 20th November 2006