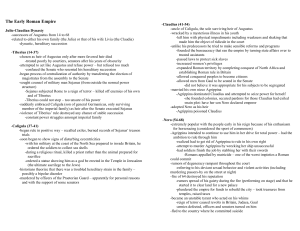

Section 1. THE ROMAN INSTITUTIONAL

advertisement