Coral reefs in crisis

advertisement

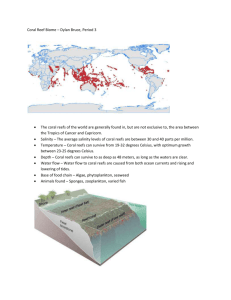

Coral reefs in crisis Coral reefs are among the most diverse and productive communities on earth. They are found in the warm and shallow waters of tropical oceans worldwide. Reefs have functions ranging from providing food and shelter to fish to protecting the shore from erosion. Because many coral reef organisms can tolerate only a narrow range of environmental conditions, reefs are sensitive to damage caused by environmental changes. Coral reefs around the world are currently under severe stress for a number of reasons. Human activity causes physical damage, pollution and sedimentation. The ocean’s rise in temperature often leads to coral bleaching, resulting in coral death. The effects of predatory organisms can also be devastating in the short term. Reef damage resulting from storm surges, particularly those associated with hurricanes, tsunamis and earthquakes, can be catastrophic. An understanding of the stresses and dangers to coral reefs is therefore necessary because of the important ecological and economic role they fulfil. Types of coral reefs Coral reefs are calcium carbonate structures, made up of reef-building stony corals. Coral grows only as deep as light penetrates, so reefs occur in shallow water up to 60 metres. This dependence on light also means reefs are only found where the surrounding waters contain relatively small amounts of suspended material and are paradoxically of low productivity. Reef-building corals live only in tropical seas, where temperature, salinity and lack of turbid water are conducive to their existence. Different types include: Fringing reefs are those that fringe the coast of a landmass. They grow in shallow waters and are usually characterised by an outer reef edge capped by an algal ridge, a broad reef flat, and a sand-floored “boat channel” close to the shore. Many fringing reefs grow along shores that are protected by barrier reefs and are thus characterised by organisms that are best adapted to low wave-energy conditions. Fringing reefs are located in Antigua in the Caribbean (see Figure 1), and in the Gulf of Aqaba in Egypt. Figure 1. Coral fringing in Antigua. Barrier reefs occur at greater distances from the shore than fringing reefs and are often separated from it by a wide deep lagoon. Barrier reefs tend to be broader, older and more continuous than fringing reefs; the Beqa barrier reef of Fiji stretches unbroken for more than 37 kilometres; that off Mayotte Island in the Indian Ocean for around 18 kilometres. The largest barrier-reef system in the world is the Great Barrier Reef, which extends 1600 kilometres along the east coast of Australia, usually tens of kilometres offshore. Another long barrier reef is located in the Caribbean off the coast of Belize between Mexico and Guatemala. Atolls reefs are ring-shaped reefs that develop at or near the surface of the sea when islands surrounded by reefs subside. They rise from submerged volcanic foundations and often support small islands of waveborne detritus. There are two types of atolls: those rising from deep seas those found on the continental shelf. Atoll reefs are essentially indistinguishable from barrier reefs except that they are confined to the flanks of submerged oceanic islands, whereas barrier reefs may also flank continents. There are over 300 atolls in the Indo-Pacific ocean. Only ten are found in the western Atlantic. The term patch reef refers to small circular or irregular reefs that rise from the seafloor of lagoons behind barrier reefs or within atolls. In his classic book Structure and distribution of coral reefs (1842), Charles Darwin outlined the way in which coral reefs could grow upwards from submerging foundations. From this study, it became clear that fringing reefs might be succeeded by barrier reefs and thence by atoll reefs in a slow process of change and development. Figure 2. A patch reef in Antigua. Threats to coral reefs Over-fishing, destruction of coastal habitat and pollution from industry, farms and households are endangering not only fish – the leading individual source of animal protein in the human diet – but also marine biodiversity and even the global climate. According to the World Resources Institute, 58 per cent of the world’s coral reefs are at high or medium risk of degradation, with more than 80 per cent of southeast Asia’s extensive reef systems under threat. Corals and coral reefs are extremely sensitive. Slight changes in the reef environment may have detrimental effects on the health of entire coral colonies. These changes may be due to natural disturbances as well as human activities. Although natural disturbances may cause severe changes in coral communities, the vast majority of decreases in coral cover and general health of a colony occur when coral reefs have been linked to human impacts on the environment. The basis for the continued degradation of coral reefs is the increasing size of the human population and its needs. Figure 3. Coral reefs offer great possibilities for tourism development. Human development of coastal regions This is one of the greatest threats to coral reefs. As development alters the landscape, the amount of freshwater runoff increases. This may carry large amounts of sediment from land-clearing areas, high levels of nutrients from agricultural areas, as well as pollutants such as petroleum-based products or insecticides. Whether it is due to direct sedimentation onto the reef or an increase in the turbidity of the water, a decrease in the amounts of light reaching corals may cause bleaching. In addition, increases in the amounts of nutrients encourage the growth of other reef organisms such as sponges that may compete with the corals for space making reefs increasingly crowded. Pollutants and toxins Flows from water treatment plants and large power plants damage coral reefs by affecting coral reproduction and development. Sewage flowing into the sea increases the nutrient levels of the water, while large power plants alter water temperatures by discharging hot water into coastal waters. The leakage of fuels into the water and the occurrences of spills by large tankers are also extremely damaging to corals. Boat anchors also damage reefs, crashing into and destroying entire colonies. The grounding of large sea-going vessels will necessarily result in large sections of coral reefs being destroyed. Overfishing Reef fish populations have greatly declined in some areas of the world. This has often lead coral reef ecosystems to become unbalanced by allowing more competitive organisms, such as algae, once controlled by large fish populations, to become dominant on the reefs. Damage has often been due to changing fishing methods. In some areas, farmers have been forced to catch fish by using fish traps with small mesh diameters in order to catch even the smallest fish. Sometimes the use of explosives or poisons is used. These methods don’t only kill all fish, but they also severely damage the corals in these areas. Natural disturbances Although much of the coral reef’s degradation is directly blamed on human impact, there are several natural disturbances that cause significant damage to coral reefs. Hurricanes and typhoons bring large and powerful waves to the tropics. These storm waves cause large corals to break apart and scatter fragments about the reefs. After the storm, slow-growing corals might easily be overgrown by quicker-growing algae. In addition, these storms generally bring heavy rain, which increases runoff and sedimentation. Generally, however, reef damage from hurricanes is comparatively short term and reparable. Another common threat to coral populations in the Pacific Ocean is the ‘crown-of-thorns’, Acanthaster planci. A. planci is a large starfish which feeds on corals. These predators have had serious effects on coral populations. Other predators such as fish and gastropods are also known to cause damage to coral colonies, but these generally do not compare to the drastic effects which A. planci has on coral populations. ‘Rainforests of the sea’ – the value of coral reefs Coral reefs are among the most biologically rich ecosystems on earth. About 4,000 species of fish and 800 species of reef-building corals have been identified. Coral reefs resemble tropical rainforests in three ways: both thrive under nutrient-poor conditions (where nutrients are largely tied up in living matter) both support rich communities through incredibly efficient recycling processes both exhibit very high levels of species diversity. Coral reefs and other marine ecosystems, however, contain more varied life forms than land habitats. The NPP (net primary productivity) of coral reefs is 2500 g/m-2/year and its biomass is 2KL g/m-2. Mangroves and coral reefs are fundamentally connected ecosystems. Mangroves protect coral reefs from sedimentation as well as helping to keep the water clear of particles and nutrients – both of these functions are necessary to maintain the health of a reef. Mangroves also provide spawning and nursery areas for many of the species of animals that spend their adult lives on the reefs. In return, the coral reefs provide shelter for mangroves and their inhabitants, while the calcium carbonate eroded from the reef provides sediment from which the mangroves take nutrients. Coral reefs are important not only for biodiversity, but also to the human population as well. Figure 4 – A flooded mangrove. Seafood In LEDCs, coral reefs contribute about a quarter of the total fish catch, providing food for up to a billion people in Asia alone. If properly managed, reefs can yield, on average, fifteen tonnes of fish and other seafood per square kilometre per year. New medicines Coral reef species offer particular hope for the development of new medicines because of the array of chemicals produced by many organisms for self-preservation. Corals are already being used as bone marrow grafts. Chemicals found within several species are already useful for treating various viruses, leukemia, skin cancer and other tumours. Other products Reef ecosystems yield a host of other economic goods, ranging from corals and shells made into jewellery and souvenirs to live fish and corals used in aquariums, to sand and limestone used by the construction industry. Recreational value The tourism industry is one of the fastest growing sectors of the global economy. Coral reefs are a major attraction for snorkellers, scuba divers and recreational fishers. Coastal protection Coral reefs buffer adjacent shorelines from wave action and the impact of storms. The benefits from this protection are widespread. They range from maintenance of highly productive mangrove fisheries and wetlands to supporting local economies built around ports and harbours, where, as is often the case in the tropics, these are sheltered by nearby reefs. Threats and responses: Montserrat Montserrat forms part of the Leeward Islands chain, a geologically young archipelago that began to form less than 50 million years ago. The reefs are a series of patch reefs interspersed with sand and sediment and are biologically diverse. There are at least 37 true coral species, 87 invertebrate, 3 seagrass, 37 algal species, and 67 fish species. Corals occupy 20–45 per cent of available space, while algae (marine plants) cover 23–41 per cent of space. In 1995, there was a decrease in the abundance of finger corals mainly due to hurricane damage. The volcanic nature of the island plays a large role in the abundance and distribution of coral reefs around Montserrat by providing high nutrient input. The Soufrière Hills volcanic eruption is depositing ash and sediment on the reefs. High nutrients favour algal (plant) growth, and algae dominate many of the reefs. However, high runoff rates from steep slopes limit the establishment of coral reefs as they are limited by the availability of a hard substrate. There are three main sediment sources on Montserrat’s reefs: volcanic ash deposition directly from the air ash and debris runoff from the land re-suspension and re-deposition of ocean sediments. Figure 5. A new delta off the southern coast of Montserrat. Continued sediment input may change the distribution and diversity of the reefs and needs to be monitored. Increased input from volcanic activities occurs from the east to the southwest of the island and sedimentation has covered some reefs in the south of the island. Sediment load changes the limit of the euphotic zone (the depth at which photosynthesis ceases to occur), and there are areas where the reef now lies below the euphotic zone. Rendezvous Bay in the north of the island has the least amount of sediment. This area is in the drier region of Montserrat. It is unaffected by sediment or ash from the volcano and water clarity is consistently high. On the other hand, Garibaldi Bluff (a steep slope offshore the island) has higher sediment loads, and the inner region of the reef (‘Garibaldi Reef’) has the highest sediment input. Shortly after a series of large ash plumes fell on Garibaldi Reef, large areas became covered in sediment, and a thin algal film started growing on the sediment and trapping it in place. The marine life under the sediment has already started to bleach and disintegrate. At Garibaldi Bluff 64 per cent of all coral colonies are bleached. All of the giant sponges have been covered in sediment, some up to 1 cm deep. In contrast, at sites unaffected by the volcano like Rendezvous Bay, none of the sponges show signs of bleaching or disintegration. Environmental threats and response: Montserrat As a result of the destruction of coral around Montserat, some scientists have called for the development of a Marine Protected Area. The development of a marine park involves: the support and education of the local community the development of clear goals for the park use of well-defined criteria to identify park areas a plan for operating, monitoring, and managing the park. There would be a zoning system, similar to that which has been successfully used in the Cayman Islands, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and Barbados (see below). There should be three main zones: fishery zones dedicated to fishing and stock enhancement marine reserve zones dedicated to education, research, conservation and recreation, with no fishing or collecting allowed a marine preserve designated as an environmental safety zone to protect reefs and fisheries and to act as a source of new recruits for the reef and fishery, with no fishing, diving or other activities except monitoring by park personnel. Environmental threats and responses: Barbados The west coast is Barbados’ premier tourism zone, noted for its up-market hotel facilities and commercial activities. There is also substantial residential development. Within the region there are four welldeveloped fringing reefs, several patch reefs and an offshore bank reef. Fish numbers are low due to historical over-fishing, poor habitat quality and a severe disease that targeted reef fish in 1994. Experiences from across the Caribbean and elsewhere clearly indicate that marine park management is fundamentally about the control of human use and the creative resolution of conflicts among user groups. The primary stakeholders in the development of marine parks geneally are: residents and businesses, including hotels located on the foreshore the watersports operators the fishermen the government agencies with responsibility for the area the beach users – locals and tourists. Numerous lessons are learned and existing knowledge confirmed by this process: The participatory approach to stakeholder analysis takes considerable time and financial resources but can provide valuable insights. Stakeholders have justifiable concerns that must be aired and addressed even if they appear to bear little relation to the project’s focus. Participatory processes are very human-intensive. Non-organised groups are difficult to engage in these processes, for example jet-skiers. Time lags are inevitable but problematic. It is not always possible or feasible to have all stakeholders represented. Folkestone Marine Park, Barbados As a result of the discussions between the stakeholders, the Folkestone Marine Park and reserve was established, with zoning adopted as the main method of monitoring. The park and reserve are located on the west coast of Barbados. The reserve stretches a total distance of 2.2 kilometres and extends a distance offshore of 950 metres at its widest point and 660 metres at its narrowest. The reserve consists of four zones: scientific zone – designated for marine research northern and southern zones – designated for fast speed watercraft use recreational zone – designated for recreation, including swimming and snorkelling. However, issues still to be addressed are: The size of the reserve – it is too small. The marine reserve covers approximately 11 per cent of the length of the west coast of the island and has a total area of 2.1 square kilometres. As it stands, the scientific zone is one-eighth of the entire area. The external impacts on the reserve – domestic waste from local wells, chemicals from fertilisers and pesticides used in local farms and golf courses. In the past, divers were accused of spear fishing and of destroying reefs to collect coral for souvenirs. Conclusion The marine environment is critical to the natural and cultural heritage of the world. Many communities depend on marine resources for their economic well-being. Coral reefs are in decline worldwide and important commercial industries such as fishing are declining as a result. There are a great number of threats to coral reefs, and most of the threats can be attributed either directly or indirectly to humans. Solutions to the many problems to the preservation of coral reefs range from better methods of development to decrease runoff to designating Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). The Caribbean region now has 104 MPAs. When well-managed, a MPA can conserve diversity, sustain fisheries and promote ecologically sensitive tourism. Whatever the solutions, there always needs to be adequate enforcement to ensure proper techniques are being followed. Unfortunately, enforcement has not been great enough in the past. Therefore, the education and co-operation of people throughout the world is necessary if coral reefs are to survive.