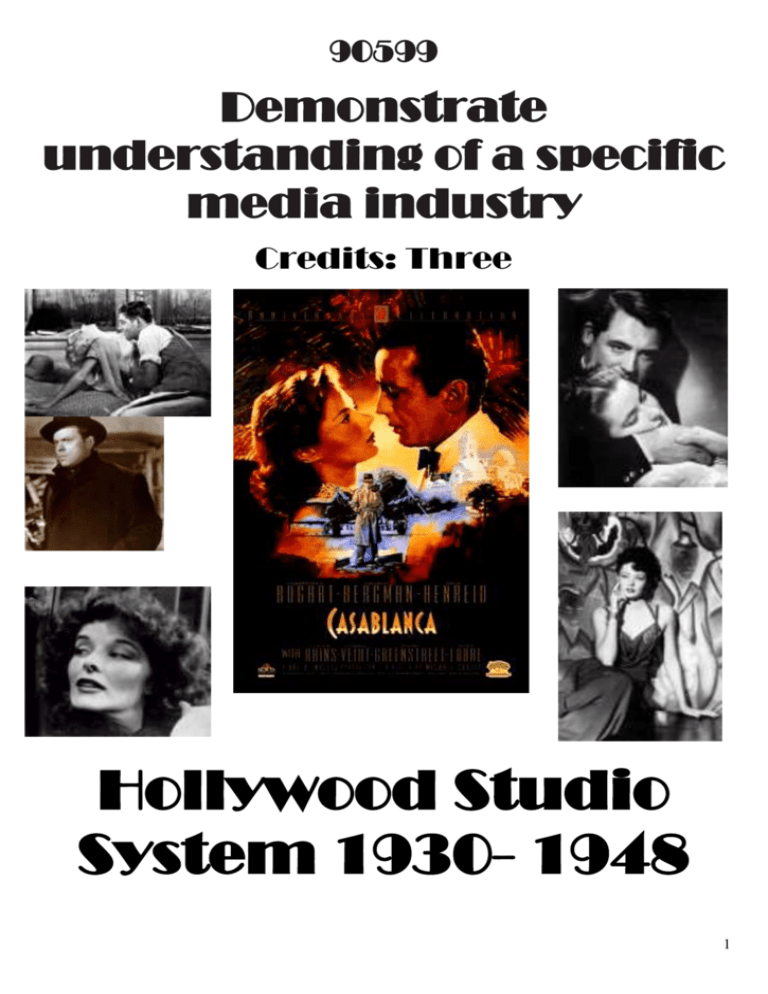

Industry: Hollywood Studio System 1920- 1946

advertisement