The purpose of this study was to explore attitudes toward menst

advertisement

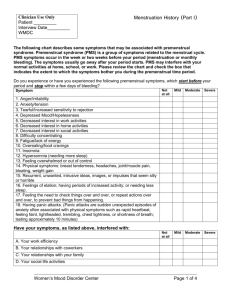

Hancock 1 Negotiating Dominant Discourse: The Social Construction of Menstruation among Students at Warren Wilson College Victoria Hancock Warren Wilson College May 9, 2010 SOC 410 Directed Research Laura Vance Hancock 2 Index Table 1: Age Table 2: Class Standing Table 3: Semesters at Warren Wilson College Table 4.1: Categorized Responses to Item 5: Mode of Introduction to Menstruation Table 4.2: Specific Responses to Item 5: Mode of Introduction to Menstruation Table 4.3: Mode of Introduction Analyzed by Gender Table 5.1: Responses to Item 6: “Who do you speak with about menstruation?” Table 5.2: Responses to Item 6 Analyzed by Gender Table 6: Menstruation as Debilitating Table 7: Menstruation as Holistic Table 8: Menstruation as Bothersome Table 9: Menstruation as Powerful Table 10: Perceptions of Debilitation Analyzed by Semester Table 11: Gendered Perceptions of Menstruation as Debilitating Table 12: Gendered Perceptions of Menstruation as Holistic Table 13: Gendered Perceptions of Menstruation as Bothersome Table 14: Gendered Perceptions of Menstruation as Powerful Table 15: Responses to Item 12: “In some ways women enjoy menstrual periods” Table 16: Gender and Item 12 Crosstabulation Table 17: Responses to Item 28: “Avoiding certain activities during menstruation is often very wise” Table 18: Gender and Item 28 Crosstabulation Figure 1: Perceptions of Menstruation as Debilitating Figure 2: Perceptions of Menstruation as Holistic Figure 3: Perceptions of Menstruation as Bothersome Figure 4: Perceptions of Menstruation as Powerful Figure 5: Perceptions of Menstruation as Debilitating According to Gender Figure 6: Perceptions of Menstruation as Holistic According to Gender Figure 7: Perceptions of Menstruation as Bothersome According to Gender Figure 8: Perceptions of Menstruation as Powerful According to Gender Figure 9: Responses to Item 12: “In some ways women enjoy menstrual periods” Figure 10: Item 12 Analyzed by Gender Figure 11: Responses to Item 28: “Avoiding certain activities during menstruation is often very wise” Figure 12: Item 28 Analyzed by Gender Hancock 3 Menstruation is a biological act fraught with cultural implications. The culturally constructed menstrual taboo is apparent in many cultures, including our own. Western taboo against menstruation is evident in popular presentations of menstruation that consistently reinforce negative perceptions. As a result of the cultural socialization of American youth, it is not surprising that dominant discourse is reflected in their attitudes toward menstruation. However, there is an increased exposure to positive representations of menstruation at Warren Wilson College. The purpose of this study is to explore whether an environment that encourages discussion about menstruation would change perceptions. Additionally, due to the lack of extant research about college students’ perceptions of menstruation, this research is also designed to explore general attitudes in order to contribute to the larger body of data. Research measured various dimensions of perception: menstruation as debilitating, holistic, bothersome, and powerful. Data indicate that the most significant differences in attitudes are between males and females. If these results are typical, it is apparent that people are socialized to internalize negative views of menstruation. Data collected during the Spring of 2010 suggest that perceptions of menstruation are well entrenched in students at the College. Although many people confront menstruation every month, discussion about menstruation is limited. By examining attitudes toward this biological function, a more comprehensive picture of the cultural construction of menstruation will become available. The purpose of this study is to understand the effects of menstrual taboo on the perceptions of menstruation among students at Warren Wilson College. Taboos about menstruation are nearly universal (Douglas 1966, Weideger 1975, Buckley and Gottlieb 1988, Delaney, Lupton & Toth 1988). Perceptions about menstruation, both negative and positive, are constructed primarily by young women's introduction to menstruation and are perpetuated by the influences of their peers, family members, and the media, among others (Delaney et al. 1988, Houppert 2000, Charlesworth 2001, Costos, Ackerman & Paradis 2002, MacDonald 2007). Studies about Hancock 4 perceptions of menstruation among American women posit that negative perceptions of menstruation may arise when the biological function of menstruation is overshadowed by conflicting messages about menstruation (Charlesworth 2001, Houppert 2000). Messages which overshadow the biological aspects of menstruation include the encouraged secrecy of menstrual management, such as negatively perceiving the purchase of menstrual products and avoidance of acknowledgment of one's menstruation. As a reflection of these negative messages, women are taught to conceal the fact that they menstruate, which Unger and Crawford call a cultural “conspiracy of silence” (1996:223). Conflicting messages are reflections of dominant discourse presented through menstrual product advertisements, primary introductions to menstruation, and communications (or lack thereof) about menstruation with peers. Charlesworth (2001), Houppert (2000), and Kissling (1996b), in exploring sexual education literature, find that the language used therein is consistently negative and that this attitude is reflected in menarchal girls' perceptions of menstruation. Literature produced by the femcare industry (as the menstrual products manufacturers call themselves) reinforces a negative cultural discourse in an effort to ensure consumers for their products. By perpetuating views of menstruation as malodorous, for example, they influence newly menstruating girls to purchase scented products that will solve this “problem”. Additionally, these advertisements also perpetuate stereotypes of femininity, encoding the cultural construction of gender with a stigma against menstruation (Kissling 2006). The notion of binary dualism is paramount in the construction of gender. As individuals are socialized, they learn to perform the roles of their gender. Subsequently, Hancock 5 the experience of menarche is inextricably connected to “becoming a woman.” The politics of gender are enforced through the construction of the Subject and the Other. “Alterity (the state of Otherness) is not inherently attached to women, but is an artifact of a male-dominated society in which the structures of law, economics, and social life work against women's ability to claim authentic subjectivity” (Kissling 2006:3). This hegemonic discourse aids in constructing perceptions of gender and gender embodied through the experience of menstruation. Symbolic Construction: The Social Meaning of Menstruation Almost every woman experiences menstruation at some time in her life, yet in the United States an underlying anxiety about this biological act prevails. This anxiety is culturally constructed, evidenced through the diversity of attitudes toward menstruation worldwide. Throughout the history of anthropology, research undertaken in the exploration of taboos regarding menstruation clearly shows that anxiety results from established taboo against menstruation (Douglas 1966, Weideger 1975, Houppert 2000, Kowalski & Chapple 2000, MacDonald 2007). Perception of taboo is a powerful force for constructing experiences, including women's experiences of menstruation. Many things—including empirical knowledge, experience, and dominant discourse and ideology—influence perceptions. A person's introduction to menstruation contributes to the formation of his or her perception, and family members, peers, school, and/or the media undertake the process of educating pre-adolescent girls and boys about this subject. Costos, Ackerman and Paradis (2002) seek to illuminate potential sources for the prevalent anxiety and negative perceptions surrounding menstruation, finding that mothers are the primary educators about menstruation (see also McKeever 1984). Costos Hancock 6 et al. also identify 73 percent of the messages received from mothers about menstruation as “negative”. In this study, mothers were the primary educators about menstruation for about half of 123 female participants (ranging in age from 26-60) (Costos, Ackerman & Paradis 2002). Of the remaining participants, 26 percent were informed by books, pamphlets, or school and 24 percent by a sister or friend. Transmission of negative messages about menstruation from mother to daughter iss “consistent with the results of previous researchers who find that, in general, menstruation is perceived in a negative way” (Costos et al. 2002:55). Analyses of media representations of menstruation and menstrual products show that negative messages also permeate educational materials (Kissling 1996b, Houppert 2000, Charlesworth 2001, Stubbs 2008, Freidenfelds 2009). Karen Houppert (2000) finds that communication about menstruation through educational materials offered by schools is predominately negative. Houppert notes that product manufacturers often provide “educational” films, speakers, and pamphlets which are primarily marketing vehicles for their products. The Proctor & Gamble (owners of Tampax and Always) website reports that their educational program reaches “approximately 83% of fifth-grade girls in the U.S.” (sic., Proctor & Gamble 2010a). This apparent diversification of the femcare industry has been routine since the early twentieth century when Kimberly-Clark (makers of Kotex) developed an education department to produce literature and media about menstruation designed for American schools. In 1984 when it was replaced, Kimberly-Clark estimated that 100 million viewers had seen The Story of Menstruation, a short educational film developed in 1957 (Freidenfelds 2009). The menstrual product industry saw opportunity to create brand loyalty through Hancock 7 disseminating educational materials in schools (Kissling 2006), thereby inserting their financial interest into one of the primary determinants of menstrual perceptions for adolescents. It is well known that advertising exists to convince a consumer of his or her “need” for a particular product. The financial interest of the femcare industry is likewise reliant on consumers' desire for their products. A fundamental aspect of their marketing strategy is to capitalize on perceptions of the menstrual taboo by making concealment and secrecy a primary selling point for their products. By perpetuating the belief that menstruation is dirty, malodorous, and a thing which needs to be concealed, product manufacturers ensure that their customers will purchase (their) products which will ease these menstrual ailments. The femcare industry wields great power in creating discourse about menstruation, as “cultural texts . . . reinforce and even help create negative attitudes toward menstruation, toward women, and toward women's bodies . . . these attitudes are exploited to enhance corporate profits” (Kissling 2006:6). The industry creates a particular perception of menstruation in order to increase the desirability and subsequent profitability of their products. A negative perception of menstruation is supported by the industry through language, as attitudes both inform and are informed by the language used to communicate about menstruation. Kane (1990) explains that the very notion of “feminine hygiene” stimulates the belief that women need a special kind of cleansing for an exclusively female filth. This “filth” can be mitigated by products promoting “freshness”, described by Kissling as “an undefined yet seemingly essential characteristic of femininity” (2006:11). Scented menstrual products are offered by almost all menstrual product manufacturers and are marketed to resolve the apparent necessity of deodorizing Hancock 8 menstrual blood. Luckily, through the purchase of scented menstrual products, one can “beguile” the senses (as advertised by one Tampax advertisement in 2005, cited in Kissling 2006:21) into believing that menstrual blood might smell like flowers – a scent associated with a common cultural symbol of femininity. It is difficult to surmise if this product is consumer-driven or if the industry creates this desire, but there is apparently a market for this type of product, as it remains on the shelves of grocery stores and pharmacies. Shauna MacDonald refers to these messages as “marketing myths”, where menstruation is cloaked in surreptitious meaning, often (mis)represented as translucent blue liquid (2007:340). MacDonald reports that in commercialized representations of menstruation, if the actual menstrual product is shown, a “disembodied hand” pours a blue liquid onto a pristine sanitary pad, creating an unrealistic representation of menstruation (2007:340). The word “menstruation” is often replaced with an ambiguous euphemism or is completely omitted. One Kotex advertising campaign featured the image of a large red dot that might be placed at the end of a sentence or as an animated embodiment squirming its way into the middle of words like “vacation” or “prom”, symbolizing a pesky or unwanted intrusion. Control of menstruation operates on both physical and linguistic levels. Advertisements encourage concealing the fact of menstruation by not using the words or practical imagery of “menstruation” or “blood”, but they also promote the use of products that will reduce the likelihood of exposing oneself as menstruating. Tampax offers “Compak” tampons, small to facilitate concealment in one's palm or pocket. The Tampax website describes their product as “protection you can keep secret . . . gotta love that” Hancock 9 (Procter & Gamble 2010b), suggesting that keeping menstruation secret is a priority while explicitly appealing to teens' linguistic cues. This is consistent with literature suggesting that women are highly motivated to conceal any sign of menstruation (Delaney, Lupton and Toth 1988, Park 1996, Houppert 2000, Kowalski & Chapple 2000, Costos et al. 2002, MacDonald 2007), indicating that women would, in fact, “love that” ability to keep their “protection” secret, as suggested on the Tampax website. The desire to conceal menstruation is evident through people's anxiety in purchasing menstrual products, the persistent fear of leakage, and the euphemisms (or dysphemisms) created to disguise conversation about the taboo topic. Female desire to conceal menstrual products is rooted in what Kowalski and Chapple call “impression management” (see also Goffman 1959). They hypothesized that the impression management surrounding menstruation results from social stigma. They find that women believe that menstruation is stigmatized and therefore alter their behavior depending on the person with whom they are interacting. This alteration in behavior indicates that women “attempt to maintain the concealed nature of the stigma” in an attempt to remove themselves from the potentiality of being discredited or becoming a “marked” figure (2000:79). Similarly, a study by Roberts, Goldenberg, Power, and Pyszczynski (2002) indicates differing impressions in college students’ interactions with a female who inadvertently drops a hair clip out of her purse and one who drops a tampon. Roberts et al. find that these students express negative reactions to the woman who dropped a tampon. They subsequently viewed her as “less competent” and “less likeable”, and tended to physically distance themselves from her by sitting farther away. This reaction Hancock 10 suggests, “women's widespread concern about concealing their menstrual status is at least somewhat justified” (2002:136). Strict menstrual management therefore attempts to prevent stigmatization. There is evidence of pervasive and persuasive cultural discourse about menstruation that is presented through advertising, by primary introductions to menstruation, and by educational materials provided at school and peers' perceptions. Menstrual products construct symbolic messages about menstruation and about femininity reinforcing negative attitudes and behaviors. The menstrual product industry has a financial interest in supporting menstrual taboos by promoting negative ideologies about menstrual odor and hygiene and supporting the concealment of menstruation. Lack of direct communication in advertising about menstruation is also a rejection of the fact of menstruation and support of the taboo. Discourse of Alterity: Menstruator as Other “This was the worst thing I had been told about, this is the day you begin womanhood, and nothing will ever be the same again.” Danielle (Interview by Costos et al. 2002) Simone de Beauvoir’s critical Feminist manifesto, The Second Sex, has left us with one of the most succinct expressions of the social construction of gender. She posits, “one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman” (1989:267). This idea is central to any discussion of constructed gender ideology, and particularly useful in exploring the social construction of symbolic messages surrounding menstruation. Perceptions of gender are culturally constructed. Subsequently, perceptions of menstruation are similarly constructed to reinforce gender norms and notions of Hancock 11 femininity. The social stigma of menstruation, appropriate menstrual management promoted by advertisements, and the construction of language surrounding menstruation collaborate to support gender distinctions that place women in the position of Other. That is, menstruation, when utilized as a symbol of femininity and womanhood, serves to distinguish females from males. In a culture where males are the creators of dominant discourse, “man defines woman not in herself but as relative to him . . . he is the Subject, he is the Absolute – she is the Other” (de Beauvoir 1989:xxii). The male Subject is the normative gender while the female is the Other. Binary constructs are commonplace in Western thought. Light/dark, mind/body, and male/female are primary examples of dichotomous opposites, yet these terms suggest a hierarchy in which the latter, marked concepts are on the female side of the binary and are supposed as inferior. Roberts et al., referring to menstruation, state that, Similar to an ethnocentric perspective on cultural differences, a patriarchal perspective on gender differences argues that since men hold the power to name, they define their own bodies and behavior as “normal” and “good”, whereas features that differentiate women from men are viewed as inferior. (2002:136) This is the world into which a girl enters menarche. Menarche is often paradoxically constructed; newly menstruating girls are congratulated on becoming women, but this congratulation is subsequently tempered with rules detailing the necessity of concealing this monumental event. Ritual is an important tool of socialization, and Dacia Charlesworth posits that “menstrual and puberty education lessons are the only rituals in which American adolescents mark their transformation from child to young adult” (2001:13). The ritual of menstrual education assists in the construction of gender performance (and subsequent performance of Hancock 12 menstruator) by reifying differences between girls and boys and by separating them for this discussion, portraying figurative and literal restrictions of communication among genders about puberty. Charlesworth notes that this separation is likely due to an increased level of comfort when asking questions about one's changing body, but it also “points to the pre-conditioning” of gender socialization and bodily shame that is already entrenched by the time of adolescence (2001:13). In her analysis of educational materials distributed in schools, Charlesworth notes that this literature stresses that the menstrual cycle is natural and normal, but continually “devalues the female body” by stressing the need to control the menstrual flow, necessitating proper management of this hygienic “crisis” (2001:19). The promotion of menstrual management is significant in educational materials and in advertising, exacting a level of fear and anxiety about failure to control one's blood. The stigma perceived by menarchal girls about managing menstrual leakage, or “accidents”, is so keenly internalized that a great deal of effort must go into menstrual management. MacDonald posits that “we do not fear the blood but rather the disorder and social excess it represents. To leak is to lose control, which is shameful” (2007:348). All children are socialized to control bodily processes, such as urinating and drooling, but women are encouraged to elevate their control of bodily process during menstruation: “By keeping menstruation hidden, we believe we control it, just as the mind controls the body” (MacDonald 2007:347). Menstrual leaks align females with the uncontrollability of the body, and desire to control menstruation is a struggle against being marked as an inferior “Other”. Dominant discourse suggests this binary dualism places females in subordinate opposition to males, Hancock 13 therefore subordinating symbols of femaleness. Just as the penis derives its privileged evaluation from the social context, so it is the social context that makes menstruation a curse. The one symbolizes manhood, the other femininity; and it is because femininity signifies alterity and inferiority that its manifestation is met with shame. (de Beauvoir 1989:315) Thus, biology and cultural construction mark women definitively as Other. As menstruation places a girl squarely in “womanhood”, de Beauvoir notes that “the menses inspire horror in the adolescent girl because they throw her into an inferior and defective category” (1989:315-316). The cultural construction of womanhood is a functional construction. Alterity seeks to reify the Subject while subordinating the Other and is a fundamental distinction in Western thought. Mary Douglas wrote that “our pollution behavior is the reaction which condemns any object or idea likely to confuse or contradict our cherished classifications” (1966:36). With regard to the social construction of menstruation, our “cherished classifications” of binary dualism are threatened by that which pollutes our notion of the feminine. Our “pollution behavior” seeks to solidify the distinctions of gender construction. Femininity as a cherished ideal in American society is reinforced by the discourse presented in menstrual product advertisements which urge females to sustain this role by remaining “fresh” and “discreet” throughout her parallel role as menstruator. The constructed ideal of femininity is contradicted by dirty, malodorous menstruation, and the contradiction of uncleanliness must therefore be hidden. Messages about embarrassment, secrecy, and feminine ideals are commonplace in menstrual product advertisements. “Because they speak directly to biological difference, feminine hygiene commercials are in a unique position to articulate this culture's Hancock 14 conception of femininity” (Kane 2000:86). This hegemonic discourse characterizes cultural views, subsequently shaping a woman’s perceptions of and experiences with menstruation, compelling women to adapt to the role that society presents for them. The discourse within which a girl experiences menarche contributes to her socialization as a woman and as Other. The opening quote of this section is significant in its description of the anxiety felt by a menarchal girl in realizing the cultural implications of her biology. Danielle's succinct quote is a direct reflection of how “discourses surrounding menarche are intimately wound up with the politics of the female body,” where “cultural discourses of the body and its menstrual secretions and cycles represent the point where power relations are manifest in their most concrete form” (Lee and Sasser-Coen 1996:7). This quote corroborates de Beauvoir's critique of what it means to “become a woman.” Methods Research was conducted during the Spring of 2010 at Warren Wilson College. Data were collected using a survey modified from an instrument designed by Jeanne Brooks-Gunn and Diane Ruble (1980) (see Appendix A for the annotated instrument). Brooks-Gunn and Ruble constructed The Menstrual Attitude Questionnaire to explore the impact of cultural beliefs on perceptions of menstruation. The survey was designed in response to the Menstrual Distress Questionnaire (Moos 1968) which is criticized for its alleged “priming” of respondents. I constructed my instrument from The Menstrual Attitude Questionnaire, modifying it to measure a selection of ideas from the more recent Menstrual Joy Questionnaire (Delaney et al. 1988). The modifications included Hancock 15 removing a number of outdated or irrelevant items and including four new items taken from the Menstrual Joy Questionnaire because they more accurately reflect modern perceptions. The instrument includes 30 items. The first six are demographical questions followed by 24 items focusing on different dimensions of perceptions of menstruation. The first four questions measure nominal demographical background of respondents: age, gender, class standing, and the number semesters enrolled at Warren Wilson College. Two questions explore the respondents’ first introduction to menstruation and their subsequent communication behaviors with regard to this topic, with respondents instructed to select “all that apply.” Items 7-30 are designed to measure four different dimensions of perception of menstruation. These perceptions are of menstruation as (1) debilitating, (2) bothersome, (3) holistic, and as (4) a powerful, positive experience. Dimensions were measured using likert-scale responses to six randomly distributed items per dimension. Perceptions of menstruation have been characterized as multidimensional, resulting from the multifarious factors that influence attitudes toward menstruation (Brooks-Gunn and Ruble 1980). Perception is influenced primarily by environmental and interpersonal experiences. Additionally, attitudes about menstruation are particularly affected by personal experiences and the contextual attitudes surrounding one's introduction to menstruation. These influences create more diverse attitudes than the dichotomous “positive” or “negative”. For example, menstruation can be perceived as a bothersome event, but one may also acknowledge menstruation as holistic. Perceptions of menstruation are therefore not constructed as binary. Hancock 16 Perceptions of menstruation as bothersome, debilitating, and holistic were originally conceptualized by Brooks-Gunn and Ruble as used in their construction of the Menstrual Attitude Questionnaire (1980). Brooks-Gunn and Ruble have conceptualized the attitude of menstruation as a bothersome event as being troubling, onerous, or otherwise annoying. They measure degrees of attitudes of debilitation by measuring menstruation's potential for limiting or mitigating a woman's performance or enfeebling or disabling certain activities. Brooks-Gunn and Ruble conceptualized menstruation also as “A Natural Event,” which I have altered to measure attitudes of menstruation as holistic. Degree of this perception is measured by respondents' identification of menstruation as an integrative, healthy, and cyclical process. I include the dimension “powerful” to measure respondents' perceptions of menstruation as an affective event, that is, one that has a beneficial impact or effect. Questions 7-30 use a Likert Scale with answers ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. When scoring the surveys, I assigned each response to each item a number between 1 and 6 according to the answer selected. For example, Item 7 reads: “Women are more tired when they are menstruating.” This item measures perceptions of menstruation as bothersome, so responses in agreement with this item are assigned a 6 (strongly agree) or 5 (agree) while responses in disagreement are assigned a 2 (disagree) or 1 (strongly disagree). “No opinion” responses are scored as 3, but in my results I assume moderate views. I pre-tested instruments among anthropology/sociology seniors. The instrument requires 5-10 minutes to complete. I designed two surveys, one for females and one as a gender-neutral survey. The sole difference between the two surveys is that the female Hancock 17 specific survey contains a mixture of questions phrased in the first person (e.g. “When I am menstruating . . . ”) and the third person, whereas the gender-neutral survey uses third person statements. I initially developed two surveys because I would have liked to explore potential differences between how women answer questions about a greater group of women (phrased in the third person) as compared to how respondents answer questions phrased in the first person. However, although female participants had the option of taking either the gender-neutral survey or the female-specific survey, the vast majority chose the female-specific survey, in too few self-identified females who responded to the gender-neutral survey. The population for this research is comprised of Warren Wilson College students above the age of 18 enrolled during Spring Semester of 2010. Using the list of classes offered this semester as a sampling frame (Spring of 2010), I employed systematic random sampling to select 14 classes of potential survey respondents. I excluded Term Four classes and classes that do not meet regularly in a classroom from the sampling frame, for example, Student Teaching, Great Books, and physical fitness classes. I contacted professors of my 14 sampled classes via email on January 27, 2010 and scheduled survey distribution in classes for the week of February 7-13. Receiving permission from all but one of the instructors, I distributed surveys during the final 15 minutes of classes. My survey distribution was preceded by an informed consent disclaimer (see Appendix B). For each class, I set up two separate piles of surveys and an empty folder at the front of the classroom to allow participants to select their own survey and return it at their leisure when they were finished. I chose to survey during class time because of the taboo nature of my research. Hancock 18 Many students may not feel comfortable speaking about menstruation with frankness. As one of my initial goals was to explore degrees of comfort when speaking about menstruation, this limitation is inherent as a part of the nature of taboo; people do not want to speak about it or confront the taboo subject in an open, direct way. I believe that I would have struggled to achieve a substantial response rate or using other sampling methods because people who are likely to volunteer to participate in my survey research are likely to be people who are already comfortable speaking about menstruation, undermining the validity and generalizability of results. This is compounded by the historically low response rate for thesis surveys. By distributing surveys in the classroom, students' time was already budgeted for academic participation. Introductions and consent by the professor likely assisted my high survey response rate. I finished survey distribution with nearly a one hundred percent response rate. Data analysis was completed using SPSS. Frequencies and correlations were examined using this software. I employed the usage of Phi and Cramer's V statistical tests to measure the statistical significance of correlations among a variety of variables. Results: Demographical Characteristics of Respondents During the week of February 7, 170 surveys were distributed to students in thirteen classes. The survey response rate was over 98 percent. One hundred and sixtyone of the surveys were viable and nine were discarded due to missing or undecipherable data. Of the viable surveys, 35.4 percent of respondents were male (n=57), 64 percent were female (n=103), and .6 percent reported their gender as “other” (n=1). As a result of Hancock 19 the small number of people who identify their gender as “other”, I have not included this respondent in my analysis of gender and attitudes toward menstruation. Just over seventy percent (70.2%) of respondents were between the ages of 19 and 21 (n=103) with 11.8 percent aged 18 (n=19) and 18.1 percent aged 22 or older (n=29) (see Table 1 for specific distributions). Respondents were nearly equally distributed according to class standing (see Table 2). This demographical profile is typical of the demographical profile of the College. Table 1 Age Valid 18 19 20 21 22 23 and above Total Frequency 19 43 33 37 17 12 161 Percent 11.8 26.7 20.5 23.0 10.6 7.5 100.0 Valid Percent 11.8 26.7 20.5 23.0 10.6 7.5 100.0 Cumulative Percent 11.8 38.5 59.0 82.0 92.5 100.0 Table 2 Class Standing Valid freshman sophomore junior senior Total Frequency 36 40 46 39 161 Percent 22.4 24.8 28.6 24.2 100.0 Valid Percent 22.4 24.8 28.6 24.2 100.0 Cumulative Percent 22.4 47.2 75.8 100.0 Just over thirty-five percent (35.4%) of respondents report attending Warren Wilson College for one year or less (n=57), 32.3 percent for 2 years (n=52), 19.3 percent for 3 years (n=31), and 13 percent for 4 years or more (n=21) (see Table 3). Hancock 20 Table 3 Semesters at WWC Valid less than one 1 or 2 3 or 4 5 or 6 7 or 8 more than 8 Total Frequency 10 47 52 31 20 1 161 Percent 6.2 29.2 32.3 19.3 12.4 .6 100.0 Valid Percent 6.2 29.2 32.3 19.3 12.4 .6 100.0 Cumulative Percent 6.2 35.4 67.7 87.0 99.4 100.0 In order to complete statistical analysis using SPSS, respondents' modes of introduction responses were nominally categorized. Responses were categorized according to prevalent ideas in the literature about how perceptions could differ according to respondents' mode of introduction. Mother, school and/or media, mixed, and 'cannot remember' were selected as primary indicators of varying perception. Most respondents—42.2 percent—responded that they experienced multiple methods of introduction (n=68). Almost nineteen percent (18.6%, n=30) were introduced exclusively by mothers. Just over seventeen percent (17.4%, n=28) were introduced by either school and/or media. The remaining 21.7 percent could not remember how they were first introduced (n=35) (see Table 4.1). Table 4.1 Categorized Responses to Item 5: Introduction to Menstruation Frequency Valid Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent mother 30 18.6 18.6 18.6 school and/or media 28 17.4 17.4 36.0 mixed 68 42.2 42.2 78.3 100.0 cannot remember Total 35 21.7 21.7 161 100.0 100.0 Hancock 21 Specifically, the three modes of introduction that were reported most frequently by respondents were 'mother', 'school', and 'cannot remember'. Table 4.2 describes the frequencies of reported introductions to menstruation, where 42.9 percent of respondents first learned about menstruation from their mother (n=69), 36 percent first learned from school (n=58), and 21.7 percent (n=35) could not remember. These responses are not mutually exclusive. When divided according to gender, differences in mode of introduction to menstruation emerge. For females, mothers, schools, and peer groups were the predominant modes of introduction (listed in order of frequency). These responses are consistent with findings in the literature. For males, “cannot remember”, “school”, and “mothers” were the responses reported most frequently. No male respondents were introduced to menstruation by a medical professional (see Table 4.3 for responses separated by gender). Table 4.2 Specific Responses to Item 5: Mode of Introduction to Menstruation Modes of Introduction Frequency Percent Mother 69 42.9 Father 8 5 Sibling/Family Member 18 11.2 Peer Group 26 16.1 Media 13 8.1 School 58 36 5 3.1 35 21.7 Medical Professional Cannot Remember Hancock 22 Table 4.3 Mode of Introduction Analyzed by Gender Females Males Modes of Introduction Frequency Percent Frequency Percent Mother 54 52.0 14 24.6 Father 3 2.9 5 8.8 Sibling/Family Member 11 10.7 7 12.3 Peer Group 19 18.4 7 12.3 Media 9 8.7 4 7.0 School 41 39.8 17 29.8 5 4.9 0 0 12 11.7 24 42.1 Medical Professional Cannot Remember Respondents were asked about the people with whom they speak about menstruation (Item 6). Responses provided include males, females, sexual partners, no one, father, mother, and medical professionals (see Appendix A). Respondents reported that they were more likely to speak with females about menstruation (82%, n=132), followed by sexual partners (64.6%, n=104) and mothers (59%, n=95) (see Table 5.1). Again, when analyzed by gender, differences become apparent. About ninety-four percent (94.2%) of females report speaking with other females about menstruation (n=97). Almost 82 percent (81.6%) report speaking with mothers (n=71) and 68.9 percent speak with a medical professional (n=71). Interestingly, female respondents report being just slightly more likely to speak with a medical professional about menstruation (68.9%, n=71) than with a sexual partner (64.1%, n=66). Males report speaking most frequently to sexual partners (69.9%, n=37), females (59.6%, n=34), and other males (40.4%, n=23) (see Table 5.2 for a gendered division of Item 6). Hancock 23 Table 5.1 Responses to Item 6: “Who do you speak with about menstruation?” Converses with Frequency Percent Females 132 82 Sexual Partner 104 64.6 Mother 95 59 Medical Professional 75 46.6 Males 72 44.7 Father 27 16.8 No One 14 8.7 Table 5.2 Item 6 (“Who do you speak with about menstruation”) Analyzed by Gender Females Males Converses with Frequency Percent Frequency Percent Females 97 94.2 34 59.6 Sexual Partner 66 64.1 37 64.9 Mother 84 81.6 11 19.3 Medical Professional 71 68.9 3 5.3 Males 49 47.6 23 40.4 Father 24 23.3 3 5.3 No One 2 1.9 12 21 Perceptions of Menstruation Data collected from students at Warren Wilson College indicate that students' attitudes toward menstruation are multidimensional, including both negative and positive perceptions. With the exception of perceiving menstruation as holistic, most respondents report moderate views. No students strongly disagree with perceiving menstruation as Hancock 24 either holistic or powerful. Just over forty percent of respondents report having moderate perceptions of menstruation as debilitating (42.2%, n=68). Responses reflect low perceptions of this dimension, meaning that more respondents do not perceive menstruation to be debilitating, with a total of 34.8 percent (n=56) disagreeing and 23 percent (n=37) in agreement with this attitude. Only one participant reports strongly agreeing that menstruation is debilitating (see Table 6 and Figure 1). Table 6 Menstruation as Debilitating very low Frequency 12 Percent 7.5 Valid Percent 7.5 Cumulative Percent 7.5 low 44 27.3 27.3 34.8 moderate 68 42.2 42.2 77.0 high 36 22.4 22.4 99.4 very high 1 161 .6 100.0 .6 100.0 100.0 Total Figure 1 Perceptions of Menstruation as Debilitating h igh yH Ver Hig rate Low Mo de Ver yL ow 50 40 30 20 10 0 It is significant that a majority of participants perceive menstruation as holistic. Only one participant reports some disagreement with this dimension, and no participants Hancock 25 highly disagreed with this perception. An overwhelming 70.2 percent of respondents (n=113) report some or strong agreement with the idea that menstruation is holistic. This seems highly significant, but due to the lack of extant research measuring this dimension in other populations, I cannot discern whether this is a typical response. The majority of respondents report some degree of perceiving menstruation as a good example of a healthy, holistic and natural process, totaling nearly 50 percent of the sample population (49.1%, n=79). Almost 30 percent report moderate views (29.2%, n=47), and 21.1 percent report having strong agreement with this dimension (n=34) (see Table 7 and Figure 2). Table 7 Menstruation as Holistic Valid Cumulative Percent Frequency 1 Percent .6 Valid Percent .6 moderate 47 29.2 29.2 29.8 high 79 49.1 49.1 78.9 34 161 21.1 100.0 21.1 100.0 100.0 low very high Total .6 Figure 2 Perceptions of Menstruation as Holistic igh yH Ver h Hig rate Low Mo de Ver y Low 50 40 30 20 10 0 Participants report mostly mixed perceptions of menstruation as bothersome. Hancock 26 Most respondents report moderate agreement with items measuring this dimension (46.6%, n=75), and almost equal numbers report some or strong agreement (29.8%, n=48), and some or strong disagreement (23.6%, n=38) (see Table 8 and Figure 3). Table 8 Menstruation as Bothersome Valid Cumulative Percent Frequency 8 Percent 5.0 Valid Percent 5.0 low 30 18.6 18.6 23.6 moderate 75 46.6 46.6 70.2 high 40 24.8 24.8 95.0 8 161 5.0 100.0 5.0 100.0 100.0 very low very high Total 5.0 Figure 3 Perceptions of Menstruation as Bothersome igh yH Ve r Hig h rate Low Mo de Ver yL ow 50 40 30 20 10 0 Perceptions of menstruation as a powerful, positive experience were overwhelmingly moderate (64%, n=103). No participant strongly disagreed with this perception, but 9.9 percent report some disagreement with this dimension (n=16). About twenty-six percent (26.1%) report that they agree or highly agree that menstruation is a powerful process (see Table 9 and Figure 4). Interestingly, more respondents perceive menstruation as powerful. Hancock 27 Table 9 Menstruation as Powerful Valid low Cumulative Percent Frequency 16 Percent 9.9 Valid Percent 9.9 103 64.0 64.0 37 23.0 23.0 96.9 5 161 3.1 100.0 3.1 100.0 100.0 moderate high very high Total 9.9 73.9 Figure 4 Perceptions of Menstruation as Powerful igh yH Ve r Hig h rate Low Mo de Ver yL ow 80 60 40 20 0 Homogenous Attitudes Toward Menstruation As a result of the predominance of positive information and discussion of menstruation at Warren Wilson College as compared to mainstream media in society, I hypothesized that attitudes toward menstruation would change over the course of students' time enrolled at the College. Data collected during this research do not support this hypothesis. Instead, time spent at the College is not correlated with attitudes toward menstruation. For example, 33 percent of First Year students do not perceive menstruation as debilitating, where 28.6 percent of Senior class students express the same attitude. Therefore, although First Year students perceive menstruation to be more highly Hancock 28 debilitating than Senior class students, Sophomore students' perceptions of this dimension were the lowest, indicating that perceptions of menstruation do not change in a statistically significant manner over time at the College (see Table 10). Data distributions do not vary in a statistically significant way according to age and class standing when correlated with different dimensions. None of these variables—age, class standing, or time spent at the College—is a significant predictor of students' attitudes towards menstruation. These data do not corroborate my original hypothesis, but there are a number of factors which support this data, so this is not especially surprising. Literature indicates that cultural perceptions of gender and menstruation are instilled through a lifelong process of socialization. Although changing attitudes could have been measured more accurately via longitudinal data, these data suggest that socialization has strongly influenced—and continues to influence—perceptions of menstruation and perceptions are well established by the time students arrive at the College. Table 10 Perceptions of Debilitation Analyzed by Semester Debilitating very low Years at One Two WWC Three Four or more Total low moderate high very high 7.0% (n=4) 0% (n=0) 12.9% (n=4) 26.3% (n=15) 34.6% (n=18) 19.4% (n=6) 33.3% (n=19) 51.9% (n=27) 45.2% (n=14) 31.6% (n=18) 13.5% (n=7) 22.6 (n=7) 1.8% (n=1) 0% (n=0) 0% (n=0) 4.8% (n=1) 23.8% (n=5) 38.1% (n=8) 19.0% (n=4) 0% (n=0) 21 7.5% (n=12) 27.3% (n=44) 42.2% (n=68) 22.4% (n=36) 0.6% (n=1) 161 57 52 31 Hancock 29 Gendered Differences in Perception Although I did not originally begin research to specifically explore correlations between gender and perceptions of menstruation, data indicate that there are significant differences between men and women and certain dimensions of perception. However, as a result of the lacuna of research exploring male and female responses to menstruation, I am unable to determine whether these results are typical. According to findings, females are significantly less likely to perceive menstruation as debilitating than males (p<.009). Nearly forty-two percent of females (41.7%, n=43) responded that they perceive levels of debilitation as low or very low, compared to 21.0 percent of male respondents (n=12). These data are significant because they show that female respondents are less likely to perceive menstruation as debilitating. As indicated by the literature, it is likely that the rejection of this perception is consistent with the struggle against being marked as Other. Male views of menstruation as more debilitating suggest that they view menstruation as being a marker of great distinction between men and women, and that they view women as enfeebled by this difference. As Table 11 and Figure 5 below demonstrate, it is clear that male respondents are also significantly more likely to have “moderate” beliefs about this dimension. This is congruous with all other dimensions, as I will elucidate further in my discussion. Hancock 30 Table 11 Gendered Perceptions of Debilitation Debilitating Gender male female Total very low 3.5% (n=2) 8.7% (n=9) 6.9% (n=11) low 17.5% (n=10) 33% (n=34) 27.5% (n=44) moderate 52.6% (n=30) 36.9% (n=38) 42.5% (n=68) Total high 26.3% (n=15) 20.4% (n=21) 22.5% (n=36) very high 0% (n=0) 57 1% (n=1) 103 .6% (n=1) 160 Figure 5 Perceptions of Menstruation as Debilitating According to Gender 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Female igh yH Hig h Ve r Low Mo d er ate Ver yL ow Male Although not statistically significant, female respondents are more likely to express the view that menstruation is “holistic” (p < .085). Although this correlation between gender and perceptions of menstruation as holistic is not statistically significant, it suggests gendered differences in perceptions of menstruation which may warrant additional future research. It is interesting to note that females are more likely to perceive menstruation as holistic than males (10.5%, n= 6 and 27.2%, n=28, respectively), with females nearly three times as likely to have very high perceptions of this dimension (see Table 12 and Figure 6). Again, males reported moderate views more frequently than females. Hancock 31 Table 12 Gendered Perceptions of Holism Holistic Gender male female Total very low low 0% (n=0) 1.2% (n=1) 0% (n=0) 0% (n=0) 0% (n=0) .6% (n=1) moderate 36.8% (n=21) 24.3% (n=25) 29.2% (n=47) Total high 50.9% (n=29) 48.5% (n=50) 49.1% (n=79) very high 10.5% (n=6) 27.2% (n=28) 21.1% (n=34) 57 103 160 Figure 6 Perceptions of Menstruation as Holistic According to Gender 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Female igh yH Hig h Ve r Low Mo d er ate Ver yL ow Male The majority of both males and females report moderate perceptions of menstruation as bothersome, although males report this degree at the rate of nearly 60 percent (59.6%). This correlation is statistically significant, with a P value of .000. Female responses are more equally distributed across the range of degrees of perception, but more female respondents believe that menstruation is some or strongly bothersome (34%, n=35) than disagree with the notion of menstruation as bothersome (26.2%, n=27). No male respondents report strong disagreement or strong agreement, but like female respondents, they do perceive menstruation to be more bothersome (22.8%, n= 13) than not (17.5%, n=10). Hancock 32 Table 13 Gender and Menstruation as Bothersome Bothersome very low Gender male female Total low 17.5% (n=10) 19.4% (n=20) 18.6% (n=30) 0% (n=0) 6.8% (n=7) 5.0% (n=8) moderate 59.6% (n=34) 39.8% (n=41) 46.6% (n=75) Total high 22.8% (n=13) 26.2% (n=27) 24.8% (n=40) very high 0% (n=0) 57 7.8% (n=8) 5.0% (n=8) 103 160 Figure 7 Perceptions of Menstruation as Bothersome According to Gender 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Female igh yH Hig h Ve r Low Mo d er ate Ver yL ow Male Both male and female respondents report overwhelmingly moderate views of menstruation as powerful. Females were more likely to report that menstruation is powerful (30.1%, n=31) as compared to male respondents (19.1%, n=11). No respondents strongly disagreed with this dimension. Table 14 Gender and Menstruation as Powerful Powerful very low Gender male female Total 0% (n=0) 0% (n=0) 0% (n=0) low 10.5% (n=6) 9.7% (n=10) 19.9% (n=16) moderate 70.2% (n=40) 60.2% (n=62) 64.0% (n=103) Total high 17.5% (n=10) 26.2% (n=27) 23.0% (n=37) very high 1.6% (n=1) 3.9% (n=4) 3.1% (n=5) 57 103 160 Hancock 33 Figure 8 Perceptions of Menstruation as Powerful According to Gender 80 60 40 20 0 h Hig Hig h Ver y Low Mo d er ate Ver y Lo w Female Male Analysis of Selected Items As a result of the gendered differences in responses toward perceptions of menstruation, I also examined responses to two items from my questionnaire that I felt might reflect a difference between male and female views. Item 12 was designed to measure perceptions of menstruation as bothersome and reads “in some ways women enjoy menstrual periods.” People who report strong disagreement with this statement were scored as perceiving menstruation as very bothersome, while responses of strong agreement indicate that menstruation is not at all bothersome. Very few respondents report strong agreement with this statement (4.3%, n=7). Just over thirty percent of respondents (30.4%, n=49) strongly or somewhat agree with this statement. Nearly 30 percent indicated “no opinion” for this item (27.3, n=44), and 42.2 percent report that they somewhat or strongly disagree with this statement (see Table 15 and Figure 9). Hancock 34 Table 15 Responses to Item 12: “In some ways women enjoy menstrual periods” Valid Cumulative Percent Frequency 7 Percent 4.3 Valid Percent 4.3 Somewhat Agree 42 26.1 26.1 30.4 No Opinion 44 27.3 27.3 57.8 Disagree Somewhat 29 18.0 18.0 75.8 39 161 24.2 100.0 24.2 100.0 100.0 Strongly Agree Strongly Disagree Total 4.3 Figure 9 Responses to Item 12: “In some ways women enjoy menstrual periods” gly D i... .. ion hat . Str on ew Som Op in .. No hat . ew Som Str on gly A gre e 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 When analyzed according to gender, responses to this item are statistically significant (p = .000). Data indicate that females are far more likely to agree that “in some ways women enjoy menstrual periods” than males. However, they are also more likely to disagree with this statement due to the fact that male respondents report “no opinion” far more frequently than females, indicating that this 59.6 percent are, in effect, taking themselves out of the sample, where only 9.7 percent of females reported “no opinion”. Only about 40 percent of male respondents selected an answer other than “no opinion” (40.4%, n=23) (see Table 16 and Figure 10). Hancock 35 Table 16 Gender and Item 12 Crosstabulation Item 12 Gender Total Strongly Agree Somewhat Agree No Opinion Somewhat Disagree Strongly Disagree 1.8% (n=1) 12.3% (n=7) 59.6% (n=34) 15.8% (n=9) 10.5% (n=6) 57 5.8% (n=6) 33.0% (n=34) 9.7% (n=10) 19.4% (n=20) 32.0% (n=33) 103 4.3% (n=7) 26.1% (n=41) 27.3% (n=44) 18.0% (n=29) 24.2% (n=39) 160 male female Total Figure 10 Item 12 Analyzed by Gender Dis ... Dis ag ree ha t ew Str o So m Female Male ng ly ion ree Op in Ag No ha t ew So m Str o ng ly Ag ree 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Item 28 reads, “avoiding certain activities during menstruation is often very wise.” This item measures perceptions of menstruation as debilitating, so respondents who strongly agree with this statement are indicating strong perceptions of menstruation as debilitating. Just over forty-five percent of respondents somewhat agree with this statement (45.3%, n=73). This is significant because this view is maligned with advertising sentiment which expresses that women are able to (and should) participate in all normal activities (providing that they are using the correct product). This view reflects traditional perceptions of menstruation, which may have been developed in youth Hancock 36 by educators. There is no medical reason that “avoiding certain activities during menstruation is often very wise,” not even scuba diving, which one participant elected to add to his response. Only 18.6 percent strongly or somewhat disagree with this statement (n=30). Twenty-three percent report “no opinion” (n=37) and 58.4 percent report some or strong agreement with this statement (n=94) (see Table 17 and Figure 11). Table 17 Responses to Item 28: “Avoiding certain activities during menstruation is often very wise” Valid Cumulative Percent Frequency 9 Percent 5.6 Valid Percent 5.6 Disagree Somewhat 21 13.0 13.0 18.6 No Opinion 37 23.0 23.0 41.6 Somewhat Agree 73 45.3 45.3 87.0 21 161 13.0 100.0 13.0 100.0 100.0 Strongly Disagree Strongly Agree Total 5.6 Figure 11 Responses to Item 28: "Avoiding certain activities during menstruation is often very wise" Som Str ong l yA gre e ewh at A gre e No Op inio Som n ewh at D is.. Str . ong ly D isa gre e 50 40 30 20 10 0 Responses correlated by gender are statistically significant (p = .003). Congruent with responses to Item 12, males reported “no opinion” more frequently than females. Hancock 37 Just over sixty-one percent of male respondents somewhat or strongly agree that certain activities should be avoided during menstruation (61.4%, n=35). Males are slightly more likely to strongly agree with this statement than female respondents. Correspondingly, female respondents are more likely to strongly or somewhat disagree with this statement (26.2%, n=27) than male respondents (3.5%, n=2). Surprisingly, equal percentages of male and female respondents reported that they somewhat agree that “avoiding certain activities during menstruation is often very wise” (45.6% for each) (see Table 18 and Figure 12). Table 18 Gender and Item 28 Crosstabulation Item 28 Strongly Disagree Gender male female Total 0% (n=0) 8.7% (n=9) 5.6% (n=9) Disagree Somewhat 3.5% (n=2) 17.5% (n=18) 13.0% (n=21) No Opinion 35.1% (n=20) 16.5% (n=17) 23.0% (n=37) Figure 12 Somewhat Agree 45.6% (n=26) 45.6% (n=47) 45.3% (n=73) Strongly Agree 15.8% (n=9) 11.7% (n=12) 13.0% (n=21) Total 57 103 161 Hancock 38 Item 28 Analyzed by Gender Female Male Som Str o ngl yA gre e ew hat Ag ree No Op Som inio ew n hat Dis agr Str ee ong ly D isa gre e 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 As a result of the frequency of respondents reporting “moderate” views, I selected two specific items to determine if categorized responses indicate moderate views or if respondents were reporting “no opinion”. Males report “no opinion” at a significantly higher frequency for two of the items that I looked at individually (nearly three times as likely for Item 12 and twice as likely for Item 28). This finding suggests that male respondents were more likely overall to answer that they had “no opinion” than female respondents. As a result, I feel that I cannot draw strong conclusions about the gender correlations in responses to different dimensions of perception. Limitations/Delimitations Research focused on the opinions of students currently enrolled in classes at Warren Wilson College during the Spring of 2010. Participants ranged in age from 1846. This population of private liberal arts college students is relatively racially, Hancock 39 ethnically, and socio-economically homogenous, with a majority of students at the college identifying as Caucasian. Due to this distinct population, generalizability of results is limited. However, the demographical profile of respondents is typical of the population of the College, so results are generalizable to the student population here. There were also a few errors with my modifications to the instrument. After printing over one hundred copies, I noticed three grammatical errors on the female specific survey which may have led to confusion among respondents. The error was one of subject agreement, where the item read, “I feel more connected to the women around them when I am menstruating,” when it should have read “I feel more connected to the women around me when I am menstruating.” Only one survey participant (someone who I know relatively well) asked me to clarify these items. Additionally, I am aware of one participant who completed the survey twice. I explicitly stated in my verbal instructions during survey distribution that participants should not take the survey if one had already done so and this statement is expressed explicitly on the instrument. Endearingly, this participant claimed that he took the survey twice because he “loved menstruation so much.” As a result of time constraints and commitments, I was unable to complete qualitative research to assist the analysis of these data. Qualitative research may have expounded upon reasons that people elected to respond in a certain way and would have assisted in further refining the instrument. Theoretical perspective would be greatly enhanced if qualitative research was undertaken because we could then explore exactly what the extremely high frequencies of “no opinion” responses from males reflect. Hancock 40 Future Research Future research would expand upon results. There is a lacuna of research regarding perceptions of menstruation in the United States, although much research explores the attitudes internationally. Research relevant to perceptions of menstruation would be significant to the femcare industry (indeed, Tambrands authored a study in 1981 to explore attitudes toward menstruation), but also relevant to the discourse of gender construction. By understanding if perceptions of menstruation are culturally constructed, we would be able to explore the construction of femininity through menstruation as an identifier of femaleness. As a result of the lacuna of research, there are many other variables which still need to be explored. Research focusing on age, class, racial/ethnic, political, and educational differences would be relevant. Due to the limited generalizability of the data, a comparative study of menstrual attitudes of a different population, perhaps one at a state school, would be particularly revealing to further understand the attitudes of college age students. Warren Wilson College seems to encourage positive representations of menstruation, which may be due to the liberal persuasion of students. Research measuring liberalness and correlating this dimension with perceptions of menstruation may give a more concrete picture of why there are more positive representations here. Data indicate that there is a significant difference in attitudes toward menstruation according to gender and could therefore be explored further. Because this was not a facet that I had originally chosen to focus on, the instrument could be modified to more accurately measure this difference, especially regarding exposure to positive or negative representations of menstruation. Additional qualitative research would also allow Hancock 41 exploration of the validity of my theoretical perspective. Research enabling the quantification of exposure to media representations would also assist my theoretical perspective by indicating whether media has a very strong effect on formation of perception. Qualitative research would be beneficial in the exploration of degrees of comfort when speaking about menstruation because it is possible that many participants would feel more comfortable completing an anonymous survey than to participate in an interview about a taboo subject. Of course, it is a very different experience to complete an anonymous survey than to speak frankly about this subject. References Brooks-Gunn, Jeanne and Diane Ruble. 1980. “The Menstrual Attitude Questionnaire.” Psychosomatic Medicine 42(5). Buckley, Thomas, and Alma Gottlieb, eds. 1988. Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation. Berkley: University of California Press. Charlesworth, Dacia. 2001. “Paradoxical Constructions of Self: Educating Young Women About Menstruation.” Women & Language 24(2). Costos, Daryl, Ruthie Ackerman, Lisa Paradis. 2002. “Recollections of menarche: Communication between mothers and daughters regarding menstruation.” Sex Roles 46(1/2). Hancock 42 Crawford, Mary, Rhoda Unger. 2004. Women and Gender: A Feminist Psychology. New York: Mcgraw-Hill. de Beauvoire, Simone. 1989. The Second Sex. New York: Vintage Books. Delaney, Janice, Mary Jane Lupton, Emily Toth. 1988. The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation. USA: Illini Books. Douglas, Mary. 1966. Purity and Danger: An analysis of the concepts of pollution and taboo. New York: Praeger. Freidenfelds, Lara. 2009. The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth-Century America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Goffman, Erving. 1959. “Chapter II: Teams,” from The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Pp. 368-380 in Social Theory: Continuity and Confrontation. Second Ed., Edited by Roberta Garner. Ontario: Broadview Press. Houppert, Karen 2000. The Curse: Confronting the Last Unmentionable Taboo: Menstruation. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Kane, Kate 1990. “The Ideology of Freshness in Feminine Hygiene Commercials.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 14. Hancock 43 Kissling, Elizabeth Arveda a. 1996. “Bleeding out Loud: Communication about Menstruation.” Feminism & Psychology 6(4). b. 1996. “'That's Just a Basic Teenage Rule”: Girls' Linguistic Strategies for Managing the Menstrual Communication Taboo.” Journal of Applied Communication Research 24(4). c. 2006. Capitalizing on the Curse: The Business of Menstruation. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers. Kowalski, Robin M., Tracy Chapple 2000. “The Social Stigma of Menstruation.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 24(1). Lee, Janet and Jennifer Sasser-Coen 1996. Blood Stories: Menarche and the Politics of the Female Body in Contemporary U.S. Society. New York: Routledge. McKeever, Patricia. 1984.” The Perpetuation of Menstrual Shame.” Women & Health 9(4). MacDonald, Shauna M. 2007. “Leaky Performances: The Transformative Potential of Menstrual Leaks.” Women's Studies in Communication 30(3). Moos, Rudolph M. 1968. “The Development of a Menstrual Distress Questionnaire.” Psychosomatic Medicine. 30:6. Park, Shelley. 1996. “From Sanitation to Liberation?: The Modern and Postmodern Marketing of Menstrual Products.” Journal of Popular Culture 30:2. Hancock 44 Proctor & Gamble. a. 2010. Always: Overview. http://www.pg.com/en_US/brands/health_wellbeing/always.shtml, accessed April 8, 2010 b. 2010. Product Detail: Tampax Compak Pearl. http://www.tampax.com/en-US/products/products.aspx, accessed April 7, 2010. Stubbs, Margaret L. 2008. “Cultural Perceptions and Practices Around Menarche and Adolescent Menstruation in the United States.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1135. Weideger, Paula. 1975. Menstruation and Menopause: The Physiology and Psychology, the Myth and the Reality. New York: Knopf. Hancock 45 Appendix A: Annotated Instrument (gender neutral instrument) Survey: Attitudes of Warren Wilson College Students Towards Menstruation This survey is designed to explore various attitudes towards menstruation among students at Warren Wilson College. This is one aspect of my research that I am conducting as part of my senior thesis in Anthropology. To ensure confidentiality, please do NOT provide your name. Because your identity will remain anonymous, there are no known risks to participants by taking this survey. Please answer as many questions as you feel comfortable. The first section consists of questions about demographic information. The second section consists of more detailed questions about menstruation. This survey should take approximately 15 minutes. There will be no compensation for participating in this survey. If you wish to contact me or have questions about my research, you may do so through the information provided below or through my thesis advisor, whose information is also provided below. Summary of this survey will be presented in a public presentation held on campus in May 2010. _____ By checking this I agree that I am 18 or older, I have read this consent, and I have never taken this survey before. Tory Hancock 774.573.2346 CPO # 7939 vhancock@warren-wilson.edu Laura Vance 828.771.5851 CPO # 6206 lvance@warren-wilson.edu SECTION 1: Please indicate your answer by marking an “X” in the box. 1. Age: _____ 2. Gender: (35.4%) Male (64%) Female (.6%) Other 3. What is your academic class standing? (22.4%) Freshman (24.8%) Sophomore (28.6%) Junior (24.2%) Senior 4. How many semesters have you been a Warren Wilson student? (6.2%) less than 1 (29.2%) 1 or 2 (32.3%) 3 or 4 (12.4%) 7 or 8 (19.3%) 5 or 6 (.6%) more than 8 5. How did you first learn about menstruation? (if multiple, mark all that apply) (42.9%) mother (36%) school (5%) father (3.1%) medical professional (doctor, nurse, Hancock 46 psychologist, etc.) (11.2%) sibling/family member (16.1%) peer group (8.1%) media (21.7%) cannot remember other, specify:____________ 6. Who do you speak with about menstruation? (mark all that apply) (44.7%) males (16.8%) father (82%) females (64.6%) sexual partner(s) psychologist, etc.) (8.7%) no one (59%) mother (46.6%) medical professional (doctor, nurse, other, specify:____________ SECTION 2: Please indicate your opinion by marking an “X”. Women are more tired when they are menstruating. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly >measures the dimension: Bothersome Women feel less connected to their physical and social environment when they are menstruating. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Holistic 9. Women are less affectionate when they are menstruating. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Powerful 10. Menstruation is something women just have to put up with. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Bothersome 11. Women expect extra consideration from friends when they are menstruating. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree > Debilitating no opinion disagree somewhat strongly Hancock 47 12. In some ways women enjoy menstrual periods. (4.3%) strongly agree (26.1%) somewhat agree disagree somewhat (24.2%) strongly disagree (27.3%) no opinion (18%) > Bothersome 13. Menstruation is an obvious example of the rhythmicity which pervades all of life. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Holistic 14. Men have a real advantage in not having the monthly interruption of a menstrual period. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Bothersome 15. Menstruation provides a way for women to keep in touch with their bodies. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Holistic 16. Women are more easily upset during their premenstrual or menstrual periods than at other times of the month. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Debilitating 17. I don't believe women's menstrual periods affect how well they do on intellectual tasks. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat > Debilitating 18. Women have higher self confidence when they are menstruating. strongly Hancock 48 strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Powerful 19. Women's sexual desire is affected when they are menstruating. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly >Powerful 20. The recurrent menstrual flow of menstruation is an external indication of a woman's general good health. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Holistic 21. Women cannot expect as much of themselves during menstruation compared to the rest of the month. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Debilitating 22. Women feel more connected to the women around them when they are menstruating. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Holistic 23. A woman's creativity is elevated during her menstrual period. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Powerful 24. Women just have to accept the fact that they may not perform as well when they are menstruating. strongly agree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly Hancock 49 disagree > Debilitating 25. Women are more vivacious when they are menstruating than when they are not menstruating. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Powerful 26. The only thing menstruation is good for is to let women know that they are not pregnant. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Bothersome 27. Menstruation is a reoccurring affirmation of womanhood. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Powerful 28. Avoiding certain activities during menstruation is often very wise. (13%) strongly agree (45.3%) somewhat agree disagree somewhat (24.2%) strongly disagree (27.3%) no opinion (18%) > Debilitating 29. I hope it will be possible someday to get a menstrual period over within a few minutes. strongly agree disagree somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly > Bothersome 30. Menstruation allows women to be more aware of their bodies. strongly agree disagree > Holistic somewhat agree no opinion disagree somewhat strongly Hancock 50 Appendix B: Verbal Instructions “Hello, my name is Tory Hancock. I am a senior in the Sociology/Anthropology Department undertaking research that will be used in my senior thesis. My research focuses on attitudes toward menstruation among students at Warren Wilson. I have constructed a survey which takes about 10 to 15 minutes to complete. Your participation is entirely voluntary: you may choose not to participate and you may terminate participation at any time without consequence. If you decide to participate, your responses will be anonymous. Do not include your name on your survey. There is no compensation for completing this survey. Information collected through this survey will be presented in aggregate form at the end of the semester during a public presentation. If you have any additional questions or concerns about this research or your participation in it, please feel free to contact me or my thesis advisor, Laura Vance [will provide with contact information]. This survey asks for demographical information and then about your knowledge and perceptions of menstruation. I will provide two versions of the same survey; one that is gender neutral and one for people who identify as women. If you identify as female, you may take either survey, but I encourage you to take the female-specific survey because I will then be able to compare survey responses. For those who do not identify as female, I encourage you to take the gender neutral survey. I will leave these two survey piles here, gender neutral on the left and female-specific on the right for you to take when you are ready. When you have finished the survey, please place it face-down in this envelope. You are free to leave at any time. Do you have any questions about this research?”