CHAPTER 10 - GeoClassroom

advertisement

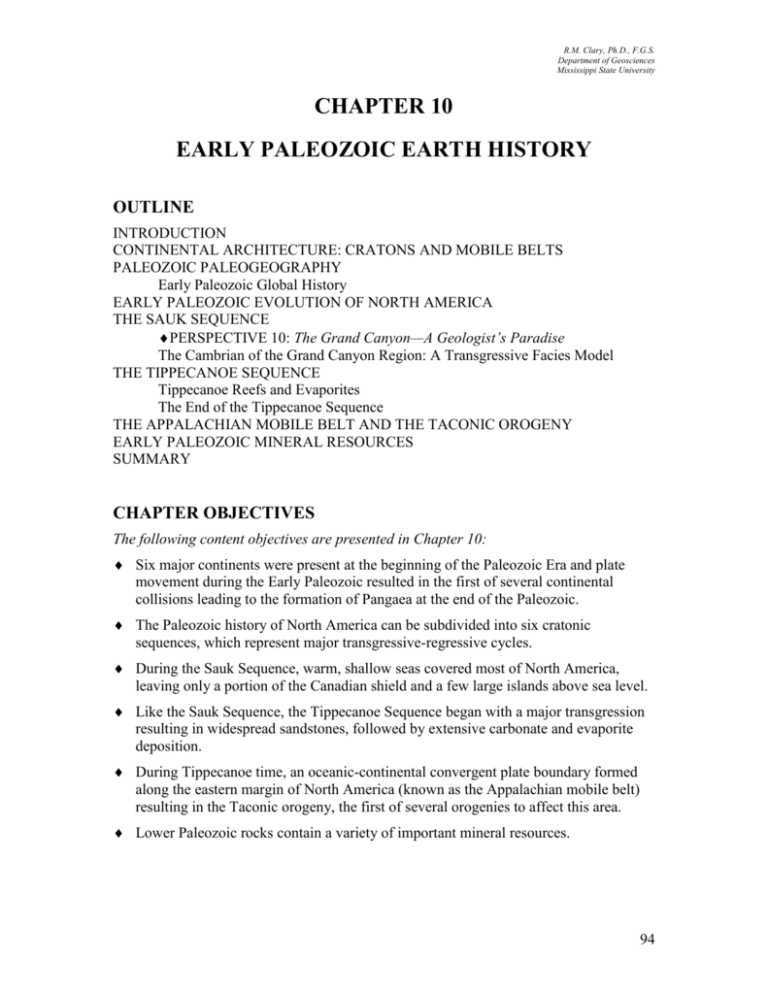

R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University CHAPTER 10 EARLY PALEOZOIC EARTH HISTORY OUTLINE INTRODUCTION CONTINENTAL ARCHITECTURE: CRATONS AND MOBILE BELTS PALEOZOIC PALEOGEOGRAPHY Early Paleozoic Global History EARLY PALEOZOIC EVOLUTION OF NORTH AMERICA THE SAUK SEQUENCE PERSPECTIVE 10: The Grand Canyon—A Geologist’s Paradise The Cambrian of the Grand Canyon Region: A Transgressive Facies Model THE TIPPECANOE SEQUENCE Tippecanoe Reefs and Evaporites The End of the Tippecanoe Sequence THE APPALACHIAN MOBILE BELT AND THE TACONIC OROGENY EARLY PALEOZOIC MINERAL RESOURCES SUMMARY CHAPTER OBJECTIVES The following content objectives are presented in Chapter 10: Six major continents were present at the beginning of the Paleozoic Era and plate movement during the Early Paleozoic resulted in the first of several continental collisions leading to the formation of Pangaea at the end of the Paleozoic. The Paleozoic history of North America can be subdivided into six cratonic sequences, which represent major transgressive-regressive cycles. During the Sauk Sequence, warm, shallow seas covered most of North America, leaving only a portion of the Canadian shield and a few large islands above sea level. Like the Sauk Sequence, the Tippecanoe Sequence began with a major transgression resulting in widespread sandstones, followed by extensive carbonate and evaporite deposition. During Tippecanoe time, an oceanic-continental convergent plate boundary formed along the eastern margin of North America (known as the Appalachian mobile belt) resulting in the Taconic orogeny, the first of several orogenies to affect this area. Lower Paleozoic rocks contain a variety of important mineral resources. 94 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University LEARNING OBJECTIVES To exhibit mastery of this chapter, students should be able to demonstrate comprehension of the following: Reconstruction methods for paleogeography the formation of and evidence for cratons, domes, and mobile belts the six major Paleozoic continents and oceans the pattern and sequence of continental movement during the Early Paleozoic the major cratonic sequences of the Early Paleozoic the importance of transgressions and regressions in the cratonic history of North America, especially as seen at the Grand Canyon the major events of the Sauk sequence the major events of the Tippecanoe sequence, with an emphasis on modern and ancient reefs and evaporites the general evolution of the Appalachian mobile belt during the Early Paleozoic with emphasis on the evidence for the Taconic orogeny the types and occurrences of Early Paleozoic mineral deposits. CHAPTER SUMMARY 1. Most continents consist of two major components: a relatively stable craton over which epeiric seas transgressed and regressed, surrounded by mobile belts in which mountain building took place. Four mobile belts formed around the margin of the North American craton during the Paleozoic: the Franklin, Cordilleran, Ouachita, and Appalachian. Figure 10.1 Major Cratonic Structures and Mobile Belts 2. Six major continents and numerous microcontinents and island arcs existed at the beginning of the Paleozoic Era. During the Early Paleozoic (Ordovician-Silurian), Gondwana moved to a southward, as indicated by tillite deposits. The microcontinent Avalonia collided with Baltica. An active convergent plate margin formed along the eastern margin of Laurentia during the Ordovician. AvaloniaBaltica collided with Laurentia to form the larger continent of Laurasia, which closed the northern Iapetus Ocean. Figure 10.2 Paleozoic Paleography 3. The geologic history of North America can be divided into cratonic sequences that reflect cratonwide transgressions and regressions. Figure 10.3 Cratonic Sequences of North America 95 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University 4. The first major marine transgression onto the craton took place during the Sauk Sequence. At its maximum, the Sauk Sea covered the craton except for parts of the Canadian shield and the Transcontinental Arch, a few large islands above sea level. Figure 10.4 Cambrian Paleogeography of North America Figure 10.5 Cambrian Rocks of the Grand Canyon Figure 10.6 Time Transgressive Cambrian Facies Enrichment Topic 1. Transgressing Seas Although climate change and rising sea levels are a current topic in the news, the transgression of the Sauk Sea reveals in the geologic record that rising sea levels have occurred at different times in our geologic past. Have students investigate projected coastlines if the East Antarctic Ice Sheet would melt. How do these projected coastline changes compare with the amount of continental crust above sea level when the Sauk Sea trangressed? Nova Online provides graphics depicting the scientific interpretation of coastlines (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/warnings/waterworld/) 5. The Tippecanoe sequence began with a transgression that deposited clean, wellsorted sandstone over most of the craton. This was followed by extensive carbonate deposition. In an addition, large barrier reefs enclosed basins, resulting in evaporite deposition within these basins. Figure 10.7 Ordovician Paleogeography of North America Figure 10.8 Transgressing Tippecanoe Sea Figure 10.9 Organic Reefs Figure 10.10 Silurian Paleogeography of North America Figure 10.11 The Michigan Basin Figure 10.12 Evaporite Sedimentation Enrichment Topic 2. The St. Peter Sandstone The St. Peter sandstone is one of the chief deposits of glass sand of the north-central US. This Ordovician sandstone is derived from the weathering of Precambrian quartzites of the Canadian Shield, which may have been a second-generation sandstone in itself. The St. Peter Sandstone is a clean sandstone, meaning that it was reworked for many years, resulting in the removal of clay-sized material. The Ford Motor Company in St. Paul actually used the St. Peter Sandstone as a source for its windshield glass for several years. E.W. Heinrich, “Geologic types of glass-sand deposits and some North American representations,” Geological Society of America Bulletin, v.92. n.9, p.611-613. A brief history of the glass industry may be found online at http://www.glassonline.com/infoserv/history.html. 6. The eastern edge of North America was a stable carbonate platform until the Middle Ordovician. During Tippecanoe time an oceanic-continental convergent plate boundary formed, resulting in the Taconic orogeny, the first of several orogenies to affect the Appalachian mobile belt. Figure 10.13 Neoproterozoic to Late Ordovician Evolution of the Appalachian Mobile Belt 96 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University 7. The newly formed Taconic Highlands shed sediments into the western epeiric sea, producing a clastic wedge geologists call the Queenston Delta. Figure 10.14 Reconstruction of the Taconic Highlands and Queenston Delta Clastic Wedge 8. Early Paleozoic-aged rocks contain a variety of mineral resources including building stone, limestone for cement, silica sand, hydrocarbons, evaporites, and iron ore. LECTURE SUGGESTIONS 1. Point out the importance of river deltas in the growth of trading and cultural centers. Modern deltas such as on the Nile, Yangtze, and Mississippi Rivers have prominent cultural development. The Queenston Delta formed in much the same way as a fluvial system; it flowed from growing highlands into the proto-Atlantic Ocean. 2. Reinforce the importance of time-stratigraphic markers by talking about the significance of Ordovician age bentonite deposits in the Appalachians. These regionally extensive bentonite deposits are interpreted to be volcanic ash layers related to island arc volcanism during the early mountain building stages of the Appalachians. They provide a widespread, datable, stratigraphic unit of uniform age within the sedimentary rocks. 3. Review how geologists reconstructed the paleogeography of the Early Paleozoic. What evidence exists for identifying continents around a paleoequator? CONSIDER THIS 1. How high were the Appalachian Mountains in the early stages of growth? Can you think of a modern analogy on Earth today? In your modern analogy, can you identify the location of where the clastic wedge is forming, or will form? 2. How does the size of one of Schloss’ cratonic sequences compare with the lithostratigraphic units (formation, group, supergroup) that were introduced in Chapter 5? 3. If the organisms throughout the Early Paleozoic resembled the Ediacaran fauna, would the carbonate deposits of the Early Paleozoic have been formed organically, or inorganically? Keep this in mind as Early Paleozoic life is discussed, in the next chapter. 97 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University IMPORTANT TERMS Appalachian Mobile Belt Baltica China clastic wedge Cordilleran mobile belt craton cratonic sequence epeiric sea Gondwana Iapetus Ocean Kazakhstania Laurentia mobile belt organic reef Ouachita mobile belt Queenston Delta Sauk Sequence sequence stratigraphy Siberia Taconic orogeny Tippecanoe Sequence Transcontinental Arch SUGGESTED MEDIA Videos 1. The Earth HAS a History, Geological Society of America 2. Sequence Stratigraphy: The Book Cliffs of Eastern Utah, Open University 3. The Record of the Rocks, Films for the Humanities and Sciences 4. Rainbow of Stone: A Journey through Deep Time in the Grand Canyon, Terra Slides and Demonstration Aids 1. Earth from Space, slide set, Educational Images, Ltd. 2. Interpretation of Roadside Geology, slide set, Educational Images, Ltd. 3. Ores of Common Metals, rock collection, Science Stuff CHAPTER 10 – ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS IN TEXT Multiple Choice Review Questions 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. b d b b b 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. e a c d b 11. c 12. e 13. d Short Answer Essay Review Questions 14. Paleozoic paleogeographic reconstructions are based primarily on structural relationships, climate-sensitive sediments such as red beds, evaporites, and coals, as well as the distribution of plants and animals. 15 . Cratonic sequences are large-scale lithostratigraphic units representing major transgressive-regressive cycles bounded by craton-wide unconformities. They are convenient for studying the geologic history of the Paleozoic because the transgressions are commonly well preserved. They are widespread and easy to map and correlate. 98 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University 16. The Cambrian Grand Canyon sequence includes the Tapeats sandstone, overlain by the Bright Angel Shale, and the Muav Limestone. This typical transgressive sequence shows the progradation of a shallow sea, from a nearshore environment, to an offshore environment, to deeper offshore. 17. Sequence stratigraphy can be used to make global correlations because the stratigraphic units were deposited over a wide area and can be found relatively easily in various locations. It is useful in reconstructing past events because it allows geologists to subdivide sedimentary rocks into related units that are bordered by time-stratigraphically significant boundaries. They can also be used for interpreting and predicting depositional environments. 18. The Appalachian margin of the Laurentian craton changed from a passive to an active margin in the Ordovician. The Taconic orogeny has the earmarks of a continent-ocean collision including volcanic activity, intrusions, and facies patterns. 19. The Michigan Basin was a nearly circular, persistently negative equatorial cratonic basin during the Paleozoic. This area became ringed with barrier reefs, which controlled the influx of sea water. As a result of high evaporative rates, concentrated brines built up within the circling reefs. 20. Carbonate deposition ceased in the Middle Ordovician, and was replaced by clastic rocks including turbidites, and volcanic sequences. Paleocurrent indicators show the location of rising Taconic highlands. Numerous unconformities, plutonic bodies, and the Queenston clastic wedge all attest to mountain-building (orogenic) processes. Apply Your Knowledge 1. Just as the Queenston Delta resulted from the erosion of the adjacent Taconic Highlands, the Catskill Delta is also the result of erosion of the adjacent Acadian Highlands. If we assume that all of the rocks from the highlands were deposited as sediments in the adjacent delta, then the volume of the sediments in the Catskill Delta was about three times the volume of the sediments in the Queenstown Delta. That means that the volume of the Acadian Highlands must also have been about three times as great as the volume of the Taconic Highlands. Because the volume of a block is length * width * height (we assume that the range is shaped like a block, which is a reasonable approximation for this exercise), we must know what the length and width of the Taconic Highlands were. We know what the volume of the Taconic Highlands is (600,000 km3 = volume of Queenston Delta, assuming the Queenston Delta represents the complete erosion of the Taconic Highlands), and the height (4000 m), so we need to know the length and width of the Taconic Highlands. If we assume that the Taconic Highlands were 600 km long, then their width would be 250 km. Thus, the size of the Taconic Highlands would be 600 km 3 * 250 km * 4 km = 600,000 km . 99 R.M. Clary, Ph.D., F.G.S. Department of Geosciences Mississippi State University If we assume that the length and width of the Acadian Highlands are the same (which seems unlikely), then the height would be three times greater or 12,000 m, if the volume of the Catskill Delta was 1,800,000 km3. It also seems unlikely that all of the sediments from both sets of highlands would end up in the adjacent deltas. 2. Paleogeographic maps are created by synthesizing various information, including paleoclimatic, paleomagnetic, paleontologic, sedimentologic, stratigraphic, and/or tectonic data that are available. However, the data are often imperfect and precise. The magnetic anomaly patterns preserved in the oceanic crust were destroyed when much of the Paleozoic oceanic crust was subducted during the formation of Pangaea. Depending upon which data are used in the reconstruction of paleogeographic maps, the maps can vary. Also, progressing research adds to our knowledge base, so older reconstructions will be (hypothetically) based on less data than more modern reconstructions. 3. Students will include a variety of information about the Grand Canyon. Some possible topics that students will address may be rock types, transgressions, sequences, unconformities, fossil information, plate tectonics, and paleogeography of the region. 100