Generalizing Results

advertisement

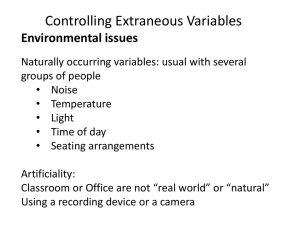

Generalizing Results Introduction to Experimental Psychology Golden West College Dr. Isonio Review—types of validity Measurement validity Internal validity “is this measure appropriately measuring what it is intended to measure?” “are the effects observed on the dependent variable(s) uniquely attributable to the independent variable?” External validity “do the findings of this apply to other populations, settings, and contexts?” Today—external validity External Validity— Focus: Generalizability of results Other aspects, some of which we have already considered: Reliability of the findings (statistical significance) Practical significance—importance, usefulness, do the results “make a difference” Effect size—is the effect (difference) large or trivial, irrespective of statistical significance Representative Samples Sampling— Probability samples assure representativeness, but in actuality samples of convenience are most typically used. Sample size—all else being equal, more participants is better than fewer Typical Participants Non-human studies— Depends much on variables being studied Very common: white rats (male albino rats of the Sprague-Dawley strain) Humans— College sophomores Approximately ¾ of all studies using human participants used college students Human participants – the College Sophomore problem Why use them college students so often? Stanovich: 3 reasons why doing so is not necessarily a problem— Reasons why it may not be a problem: 1. Using them does not invalidate findings; only requires follow-up tests to check on generalizability Cozby: generalization as statistical interaction Reasons why it may not be a problem 2. when basic psychological processes (e.g., perception, functioning of nervous system) are being studied, they are not unlike the rest of the population Clearest exception: Social psychology Cultural differences, collectivist/individualist, field dependent / independent dimensions Participant characteristics that can matter Sex Age Race / ethnicity Others: SES, family structure, education level Other dimensions to consider Location - country, state, community Setting – college campus, laboratory, participant’s home Reasons why it may not be a problem 3. College students are now a more diverse group Yet—still, at many colleges and universities: fairly homogeneous with reference to: Intelligence, life-experiences, attitudes, values, goals, self-identity development Volunteers . . . do they differ from the rest of the population?? The Volunteer Subject Many studies have examined characteristics of volunteer subjects and have shown such subjects are: More sociable Have a greater need for approval Are less authoritarian Generally are of higher social-class status Have a greater need for arousal / sensation-seeking Are less anxious Are more well-adjusted psychologically As students, earn better grades Perhaps indicates higher achievement motivation level Participant characteristics and type of study volunteered for— People generally are much more willing to volunteer for studies on attitudes, personality than for those on learning which might entail some type of punishment or harm Males—more inclined to volunteer for studies on hypnosis, sensory deprivation, interview on personal topics such as sex Females—generally more willing to volunteer than are males; prefer studies that don’t involve “unusual tasks or situations” External inference - Bottom line question— Does this study have anything to do with how variables relate in the world beyond the laboratory?? Laboratory to world External inference: Mundane realism – does the experiment “look and feel like” events in the real world? Experimental realism – are participants impacted by and engaged with the experiment; are they involved and do they take it seriously? Methodological limitations Use of a pre-test Pretests, as helpful as they can be, nevertheless can limit the generalizability of the findings to populations that did not get the pretest and can serve as a source of demand characteristics for participants Can use Solomon-four design to assess Compare conditions with, and without the pretest—does it make a difference? Solomon-four Design 1: pretest 2: pretest 3: - 4. - IV -IV -- posttest posttest posttest postest Here, we would expect a 1 and 3 versus 2 and 4 difference due to the effect of the IV, but would not expect (or want) 1 versus 3 and 2 versus 4 differences Methodological limitations Experimenters Personal characteristics of the experimenter(s) The concern is that the results might only apply to certain types of experimenters who behave in specific ways. Generalization via Literature Reviews and Meta-analyses Literature Review—a written summary and synthesis of a large body of research in a given domain. Potential problems: common measure?, file-drawer problem, which studies to include? e.g., Is schizophrenia a progressive neurodevelopmental disorder (handout) e.g., Life events and bipolar disorder (handout) Generalization via Literature Reviews and Meta-analyses Meta-analysis—a statistical evaluation of the strength and generality of a given effect Potential problems: jugdments regarding emphasis and interpretation e.g., How children and adolescents spend time (hanout) e.g., Gender differences in self-esteem (handout) Generalization via Replication Direct (exact) replication Conceptual replication Summary: Campbell & Stanley’s list of Threats to External Validity Interaction Interaction effect of testing effects of selection biases and the experimental treatment Reactive effects of experimental arrangements Multiple-treatment interferences Connectivity Principle Stanovich: the notion that there is a network of concepts in science that, collectively, constitute our understanding in an area. A new theory (or research finding) must connect to previously established facts Psychology operates more under the “gradual synthesis” model rather than the “great leap” model How important IS external validity? How does it compare to internal validity? The Importance of External Validity— Differing Views We are not examining genuine behavior in realistic ways: “In order to behave like scientists we must construct situations in which our subjects . . . can behave as little like human beings as possible and we do this in order to allow ourselves to make statements about the nature of their humanity” -Bannister, 1966, p. 24 The Importance of External Validity— Differing Views Artificiality is a critical problem: “The greatest weakness of laboratory experiments lies in their artificiality. Social processes observed to occur within a laboratory setting might not necessarily occur within more natural social settings.” Babbie, 1975, p. 254 The Importance of External Validity— Differing Views It is not a problem: “The problem of external validity is often either meaningless or trivial, and a misplaced preoccupation with it can seriously distort our evaluation of a research study.” Mook, 1983, p. 381 The Importance of External Validity— Differing Views The term itself creates unrealistic and erroneous expectations: On problems with the term “external validity”: “Who wants to be invalid—internally or externally, or in any other way? One might as well ask for acne. In a way, I wish we still used the term generalizability, precisely because it does not sound so good. It would then be easier to remember that we are not dealing with a criterion, like clear skin, but a with a question, like “How do I get the sofa down the stairs?” One asks that question if, and only if, moving the sofa is what one wants to do.” Mook, 1983, p. 379 When artificiality can be good/necessary Mook—In defense of external invalidity: Demonstrate the power of a phenomenon—show that it occurs even under trivial, contrived conditions e.g., aggression – gun as a stimulus cue Use the lab setting to create a situation that does not have a counterpart in real life When artificiality can be good/necessary Mook—In defense of external invalidity: When we ask whether something can happen, rather than that it does happen e.g., extreme obedience Prediction from theory specifies something that ought to happen in the lab (even though it does not generally happen in the real world) e.g., Consider Aggression- Read the scenarios in the handout—does #2 have anything to do with #1?? Do artificial studies/measures differ from “real life” ones?— The case of aggression Oral, written, physical indices of aggression correlate at between .70 and .80 Outside: male rate of assault and murder is 10x that of females; difference holds for physical aggression but not for verbal hostility Inside: males much more physically aggressive; verbal hostility—no strong differences Buss-Durke Hostility Inventory—predicts aggression equally well in lab and real world Do artificial studies/measures differ from “real life” ones?— The case of aggression Type A pattern—more aggressive than Type B—holds for inside and outside of laboratory Media violence—associated with increased violence both inside and outside of laboratory Anonymity/deindividuation—strong precursor to violence both in lab and outside of lab Temperature—associated with greater hostility, both in lab and out Sometimes generalization is not the goal e.g., survey research when a specific population is targeted—such as all GWC students Another perspective- Does psychological research conducted in artificial settings improve lives This is, in a sense, the ultimate “does it matter” question