Informatics Competencies: Annotated Bibliography

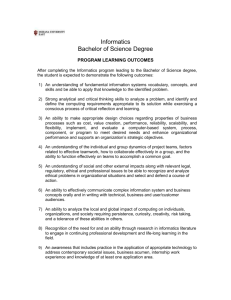

advertisement

Informatics Competencies: Annotated Bibliography Prepared by: Patricia Hinton Walker, PhD, RN, FAAN 1. Abraham, I.G. Evers. et al(1991). “A summer institute on computer Applixcations for nursing management: background, curriculum, and evaluation.” Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing .22(4): 136-42. Nursing managers are faced with a growing number of computer applications for nursing management, yet they may lack the educational preparation to assist them in using these technologiies for problem-solving and decision-making. This article describes a Summer Institute on informatics applications for nursing management taught by an international and multidisciplinary team of faculty members, and offered at the University of Limburg (Maastricht, The Netherlands). A discussion of professional, scientific, and educational issues serves as the foundation for curriculum content and instructional format. Evaluation data from both offerings are reviewed and underscore the professional relevance and didactic quality of the Summer Institute. The Summer Institute is presented as a possible model of continuing education in computer applications for nursing management transferable to Western European and North American countries. 2. Arnold, J. M. (1996). "Nursing informatics educational needs." Computers in Nursing 14(6): 333-9. A survey was conducted among 497 respondents in a northeastern metropolitan area to determine the informatics educational needs of professional nurses. All subjects were asked to indicate on a four-point scale their current knowledge and their desired knowledge in 23 content areas. The population was subdivided into three subsamples based on job classification. There were differences in the informatics educational needs of nurse educators, nurse managers, and informatics nurses. There was interest in returning to school for a graduate degree or certificate in nursing informatics by a majority of the sample, although 71% of the respondents already possess a higher degree. 3. Axford, R. and B. McGuiness (1994). "Nursing informatics core curriculum: perspectives for consideration & debate." Informatics in Healthcare Australia 3(1): 5-10. Computer applications for nursing have developed to such an extent over the past decades that a subspecialty, nursing informatics has now been defined for the profession. Knowledge development and dissemination in nursing informatics has focused on the intricacies of the technology and nurses responses to computers. Less attention has been given to nursing information per se and to the potential impact of electronic information processing upon it. In the 1990's this deficit is beginning to be addressed. Possibilities for core curriculum content begin with a clear understanding of the concept of nursing informatics and an examination of how educators throughout the world have incorporated this content into their curricula. An expansion of existing frameworks for pre-service undergraduate education is offered as a basis for further discussion and development. 4. Bickford, C. J., K. Smith, et al. (2005). "Evaluation of a nursing informatics training program shows significant changes in nurses' perception of their knowledge of information technology." Health Informatics Journal 11(3): 225-35. A survey of nurses attending a Weekend Immersion in Nursing Informatics (WINI) program showed a statistically significant change in the nurses' perception of information technology (IT) and of their ability to apply IT to affect the quality of patient care. Attendees first identified their level of expertise based on the Informatics Competencies for Nurses at Four Levels of Nursing Practice, and then completed surveys pre- and postprogram attendance to measure their personal assessments of their knowledge and abilities in specific areas of nursing informatics, information technology, and healthcare information systems. Such personal assessments are mandated in the professional standards of nursing informatics practice. (C) 2005 SAGE Publications Ltd. 5 .Booth, R. G. (2006). "Educating the future eHealth professional nurse." International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship 3(1): 1-10. Nursing is at the cusp of a truly revolutionary time in its history with the emergence of electronic health (eHealth) technologies to support client care. However, technology itself will not transform healthcare without skilled practitioners who have the informatics background to practice in this new paradigm of client care. Nurse educators have been slow to react to the matter of the necessary knowledge, skills, and practice competencies required for nurses to function as eHealth practitioners. Specifically, undergraduate nursing education must take a proactive stance towards curriculum development in the areas of eHealth and informatics. The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to propose recommendations about the review and redesign of nursing curricula in relation to nursing informatics. Recommendations include increased information literacy education, interdisciplinary collaboration, and clientcentred technologies. Recommendations for faculty development in nursing informatics are also provided. 6. Carty, B. (2001). "Nursing informatics: the future is now." Journal of the New York State Nurses Association 32(1): 11-4. Nursing informatics is a new and evolving specialty. The potential for specialists in this area of practice to influence the nursing profession, affect healthcare delivery, and participate in the design and development of future healthcare systems is remarkable. This paper explores the nature of nursing informatics, the educational preparation, and the variety of roles within the specialty. 7. Carty, B. and J. Kelly (2001). "A collaborative model for nursing informatics education within an urban enterprise system." ITIN 13(2): 4-8. Although the need for nurses with expertise in clinical informatics persists, the availability of specialised programs in nursing education continues to be insufficient to meet the demand. This paper describes the development of a graduate program in nursing informatics that emphasises collaboration among disciplines and focuses on a strong clinical component to ensure the integration of theory in the clinical informatics setting. Two years prior to the enrolment of the first class, an extensive plan was devised which included the development of a comprehensive curriculum, the inclusion of clinical affiliates to insure adequate clinical experience, and the identification of potential faculty who would reflect disciplinespecific, as well as interdisciplinary, philosophies in the new curriculum., As a result, the curriculum integrates both a nursing domainspecific as well as an interdisciplinary model of education. In addition students experience a rich variety of clinical learning environments and are mentored by faculty in clinical settings as diverse as home health and acute care settings. Clinical and course projects are developed within the context of "real world" situations and students are required to complete 600 hours of clinical experience prior to graduation. Students work in clinical dyads to enhance and develop systems for the delivery and research of clinical care. 8. Curran, C. R. (2003). "Informatics competencies for nurse practitioners." AACN Clinical Issues: Advanced Practice in Acute and Critical Care 14(3): 320-30. Informatics knowledge and skills are essential if clinicians are to master the large volume of information generated in healthcare today. Thus, it is vital that informatics competencies be defined for nursing and incorporated into both curricula and practice. Staggers, Gassert, and Curran have defined informatics competencies for four general levels of nursing practice. However, informatics competencies by role (eg, those specific for advanced practice nursing) have not been defined and validated. This article presents an initial proposed list of informatics competencies essential for nurse practitioner education and practice. To this list, derived from the work of Staggers et al., 1 has been added informatics competencies related to evidence-based practice. Two nurse informaticists and six nurse practitioners, who are program directors, were involved in the development of the proposed competencies. The next step will be to validate these competencies via research. 9. Gassert, C. A. (1998). "The challenge of meeting patients' needs with a national nursing informatics agenda." Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 5(3): 263-8. Information has become a capital good and is focused on outcomes. Clinical guidelines are being developed to standardize care for populations, but patient preferences also need to be known when planning individualized care. Information technologies can be used to retrieve both types of information. The concern is that nurses are not adequately prepared to manage information using technology. This paper presents five strategic directions recommended by the National Advisory Council on Nurse Education and Practice (Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Nursing) to enhance nurses' preparation to use and develop information technology. The recommendations are 1) to include core informatics content in nursing curricula, 2) to prepare nurses with specialized skills in informatics, 3) to enhance nursing practice and education through informatics projects, 4) to prepare nursing faculty in informatics, and 5) to increase collaborative efforts in nursing informatics. The potential impact of these strategic directions on patients is discussed. 10. Grobe, S. J. (1989). "Nursing informatics competencies." Methods Inf Med 28(4): 267-9. The purpose of the paper is to present both the processes and the results of a task force organized to recommend nursing informatics competencies for practicing nurses, nurse administrators, nurse teachers and nurse researchers. The competencies are designed to be useful in preparing nurses for their specific roles. The criterion for inclusion of a specific informatics competency statement was task force consensus. 11. Hebert, M. (2000). "A national education strategy to develop nursing informatics competencies." Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership 13(2): 11-4. Advances in the sophistication of information and communication technologies offer nursing practitioners opportunities for better information management, more complete documentation of their work, and knowledge development to support evidence-based nursing practice. However, a nursing culture that recognizes and adopts the contributions of technology to practice is required to take advantage of these opportunities. The nature of this change suggests a shift in emphasis from specialists in Nursing Informatics (NI) to NI being integrated into all four domains of nursing practice. The magnitude of change required on individual, organizational and professional levels points to the need for Nursing Informatics education strategies on a national level. Recognizing the role and history of NI specialists, defining NI and the required NI competencies are necessary first steps in developing such a plan. Expanding and adapting the educational infrastructure required to support this initiative follows. A working committee at the national level with representatives from a number of stakeholder groups is currently working on a National Nursing Informatics Project to address these issues. This article summarizes key points of an initial discussion paper. 12. Magnus, M. M., M. C. Co, Jr., et al. (1994). "A first-level graduate studies experience in nursing informatics." Computers in Nursing 12(4): 189-92. The authors describe a nursing informatics experience for first-level graduate students in nursing. Three content areas were included in the course: 1) achieving mastery of basic computer competencies; 2) evaluating emerging patterns and trends in electronic information processing; and 3) establishing electronic connection. 13. McNeil, B. J., V. Elfrink, et al. (2006). "Computer literacy study: report of qualitative findings." Journal of Professional Nursing 22(1): 52-9. Computer literacy and information literacy are critical to the future of nursing. The very nature of health care is being transformed in response to environmental drivers such as the demands for cost-effective delivery of high quality services and enhanced patient safety. Facilitating the quality transformation depends on strategic changes such as implementing evidence-based practice (), promoting outcome research (), initiating interdisciplinary care coordination [Zwarenstein, M., Bryant, W. (2004). Interventions to promote collaboration between nurses and doctors. The Cochrane Library(I)], and implementing electronic health records (). Information management serves as a central premise of each of these strategies and is an essential tool to facilitate change. This report of the analysis of qualitative data from a national online survey of baccalaureate nursing education programs describes the current level of integration of the computer literacy and information literacy skills and competencies of nursing faculty, clinicians, and students in the United States. The outcomes of the study are important to guide curriculum development in meeting the changing health care environmental demands for quality, cost-effectiveness, and safety. Copyright (C) 2006 by Elsevier Science (USA). 14. McNeil, B. J., V. L. Elfrink, et al. (2003). "Nursing information technology knowledge, skills, and preparation of student nurses, nursing faculty, and clinicians: a U.S. survey." Journal of Nursing Education 42(8): 341-9. Because health care delivery increasingly requires timely information for effective decision making, information technology must be integrated into nursing education curricula for all future nurse clinicians and educators. This article reports findings from an online survey of deans and directors of 266 baccalaureate and higher nursing programs in the United States. Approximately half of the programs reported requiring word processing and e-mail skill competency for students entering nursing undergraduate programs. Less than one third of the programs addressed the use of standardized languages or terminologies in nursing and telehealth applications of nursing. One third of the programs cited inclusion of evidence-based practice as part of graduate curricula. Program faculty, who were rated at the "novice" or "advanced beginner" level for teaching information technology content and using information technology tools, are teaching information literacy skills. The southeastern central and Pacific regions of the United States projected the greatest future need for information technology-prepared nurses. Implications for nurse educators and program directors are discussed. 15. Roberts, J. M. (2000). "Developing new competencies in healthcare practitioners in the field." Stud Health Technol Inform 72: 73-6. The Life-long Learning concept is one which is appropriate for those who have (or create) the opportunities to develop their competencies once they are in an operational role. All models of healthcare delivery and management are VOLATILE and therefore the way of addressing new competencies cannot be prescriptive or stand still for too long, but the concepts do endure. Learning, in order to 'keep up to date' is very necessary--technology, new clinical practices and interventions, new drug interactions, increased patient demands ... all add to the need to move with the times. This paper addresses some of the issues surrounding this challenge in the domain of informatics in support of healthcare delivery and management. 16. Smith, M. A. (2002). "Efficacy of web-enhancement on student technology skills." On-Line Journal of Nursing Informatics 6(3): 6p. Healthcare institutions have increased technology use in patient management prompting integration of technology into nursing education. Transitioning courses from place-based (on-site) to web-based can be time intensive and stressful for students and faculty. Web-enhancement can serve as a transitioning technique, which would allow gradual introduction to software applications throughout the semester for both students and faculty. Access to faculty and course materials can be facilitated with this technological intervention. Through web-enhancement, students can take an active role in their learning. Web-enhancement can facilitate integration of technology competencies into nursing curricula. 17. Staggers, N. and C. M. Lasome (2005). "RN, CIO: an executive informatics career." CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing 23(4): 201-6. The Chief Information Officer (CIO) position is a viable new career track for clinical informaticists. Nurses, especially informatics nurses, are uniquely positioned for the CIO role because of their operational knowledge of clinical processes, communication skills, systems thinking abilities, and knowledge about information structures and processes. This article describes essential knowledge and skills for the CIO executive position. Competencies not typical to nurses can be learned and developed, particularly strategic visioning and organizational finesse. This article concludes by describing career development steps toward the CIO position: leadership and management; health-care operations; organizational finesse; and informatics knowledge, processes, methods, and structures. 18. Yee, C. C. (2002). "Identifying information technology competencies needed in Singapore nursing education." CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing 20(5): 209-14. The purpose of the study was to identify Singapore's healthcare industry's minimum information technology (IT) performance standard expectations for nurses' competencies. A needs assessment was conducted with a panel representing nursing education, nursing management and nursing practice. The findings in this study would provide suggestions to improve the current diploma and advanced diploma nursing programs curricula to meet the present workforce demands. The experts agreed that information technology is necessary and there were two main categories of IT skills identified, basic IT skills and work-related IT skills. 19. (2004). "Emerging technologies center. Informatics competencies." Nursing Education Perspectives 25(6): 312. 20. Weaver, C. A. and D. Skiba (2006). "ANI connection. TIGER Initiative: addressing information technology competencies in curriculum and workforce." CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing 24(3): 175-6.