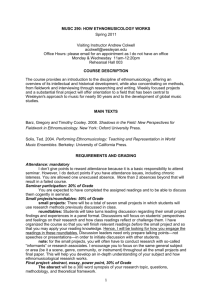

2001 Royal Holloway One Day Programme and abstracts

advertisement

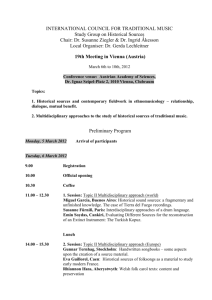

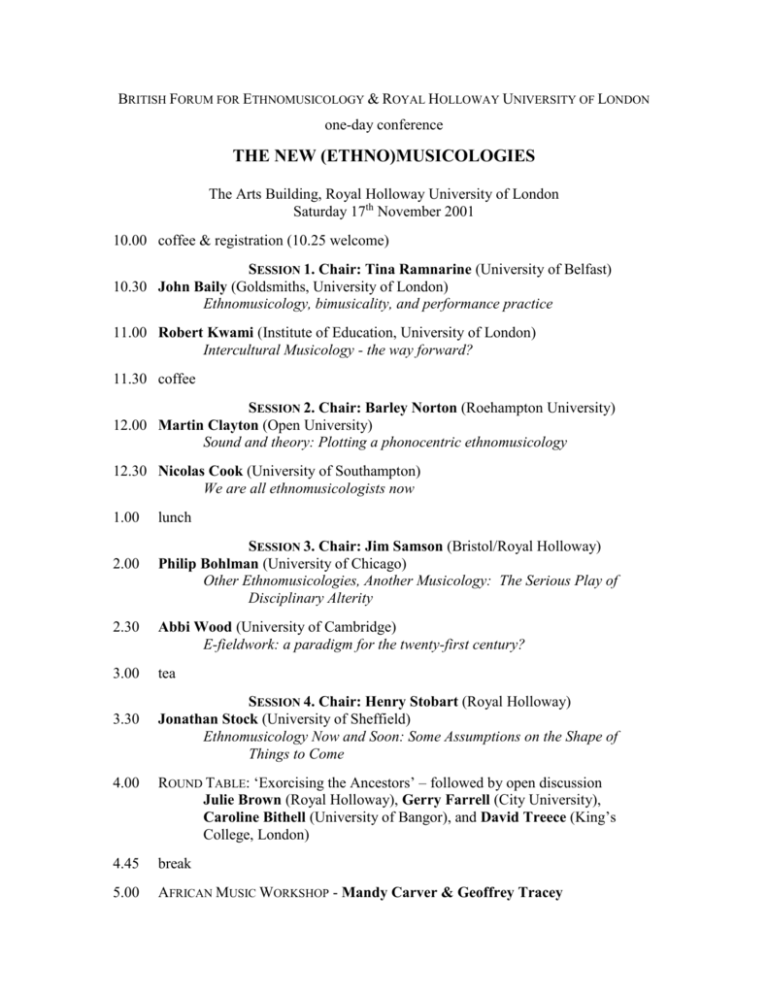

BRITISH FORUM FOR ETHNOMUSICOLOGY & ROYAL HOLLOWAY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON one-day conference THE NEW (ETHNO)MUSICOLOGIES The Arts Building, Royal Holloway University of London Saturday 17th November 2001 10.00 coffee & registration (10.25 welcome) SESSION 1. Chair: Tina Ramnarine (University of Belfast) 10.30 John Baily (Goldsmiths, University of London) Ethnomusicology, bimusicality, and performance practice 11.00 Robert Kwami (Institute of Education, University of London) Intercultural Musicology - the way forward? 11.30 coffee SESSION 2. Chair: Barley Norton (Roehampton University) 12.00 Martin Clayton (Open University) Sound and theory: Plotting a phonocentric ethnomusicology 12.30 Nicolas Cook (University of Southampton) We are all ethnomusicologists now 1.00 2.00 lunch SESSION 3. Chair: Jim Samson (Bristol/Royal Holloway) Philip Bohlman (University of Chicago) Other Ethnomusicologies, Another Musicology: The Serious Play of Disciplinary Alterity 2.30 Abbi Wood (University of Cambridge) E-fieldwork: a paradigm for the twenty-first century? 3.00 tea 3.30 SESSION 4. Chair: Henry Stobart (Royal Holloway) Jonathan Stock (University of Sheffield) Ethnomusicology Now and Soon: Some Assumptions on the Shape of Things to Come 4.00 ROUND TABLE: ‘Exorcising the Ancestors’ – followed by open discussion Julie Brown (Royal Holloway), Gerry Farrell (City University), Caroline Bithell (University of Bangor), and David Treece (King’s College, London) 4.45 break 5.00 AFRICAN MUSIC WORKSHOP - Mandy Carver & Geoffrey Tracey ABSTRACTS Ethnomusicology, Bimusicality and Performance Practice John Baily (Goldsmiths College, University of London Amongst various areas for the future development of ethnomusicology there seems to be a growing interest in performance. Hood's original argument for acquiring bimusicality was that "training in basic musicianship is fundamental to any kind of musical scholarship". Beyond that, a number of ethnomusicologists have used learning to perform as a research technique in ethnomusicological fieldwork. This paper examines a number of benefits that may follow from learning to perform, and will argue that it should form a central place in ethnomusicological research methodology. Furthermore, learning to perform should not simply be seen as a way of conducting fieldwork; achieving a high level of performance ability in a particular genre should be one of the goals of the ethnomusicologist. In the early stages of engagement with another music culture performance (as a research technique) undoubtedly informs the formulation of theory; but later on we find that theoretical realisations inform performance. These issues will be discussed with reference to performance as a component of a masters programme in ethnomusicology, and as the main objective in a doctoral programme in performance practice. Other Ethnomusicologies, Another Musicology: The Serious Play of Disciplinary Alterity Philip V. Bohlman (University of Chicago) What makes ethnomusicology ‘new’ at any given moment in its history? Does, in fact, the will to engage with otherness and to claim disciplinary identity make it necessary for the field to break with its past in order to lay claim to a distinctive future? Do disciplinary newness and innovation result from a desire for scientific turf that denies music a privileged or essentialized position? In the present moment of announcements and pronouncements about new disciplines, has ethnomusicology truly begun to move in new directions or are we witnessing attempts to rescue newness from a more pervasive otherness? More to refine than to answer such questions, this paper will be an historiographical examination of moments when ethnomusicology has consciously responded to revolutionary moments marked by claims of newness, especially those that resonate with more sweeping intellectual movements predicated on a ‘new science’ (e.g., Vico or Herder at the beginning and end of the eighteenth century). Whereas my earlier attempts to look comprehensively at the intellectual history of ethnomusicology have called for greater attention to ‘persistent paradigms’, this paper assumes what many might regard as a new approach to the field’s past, one which looks more critically at the insistent rhetoric of innovation that has urged many ethnomusicologists to break with rather than maintain tradition. I take the metaphors of my title seriously, structuring the paper as an historical drama that might provide a discursive framework to represent the long-overdue history of ethnomusicology. Sound and theory: Plotting a phonocentric ethnomusicology Martin Clayton (Open University) Since the days of Vergleichende Musikwissenschaft, our field has drawn on the methods and theories of several other disciplines, as comparative musicologists and ethnomusicologists have struggled to make their voices heard in Western academic discourse. Beginning with Stumpf, scholars applied techniques derived from experimental psychology, allied to a speculative evolutionist view of music history, in establishing what they hoped would be an important new scientific discipline. Their paradigm has been replaced by a succession of models, borrowed from disciplines inclding anthropology, linguistics, psychology, and latterly cultural studies. Each of these adaptations has been an advance in terms of increasing methodological sophistication, and has contributed to our understanding of musical phenomena. Nonethless, ethnomusicology has a poor record when it comes to generating intellectual breakthroughs. This paper argues that ethnomusicologists need to find the confidence to pursue theories grounded in real human experiences of organised sound, rather than adapting models based on studies of linguistic communication, visual representations or socioeconomic processes. We need to develop new phonocentric paradigms, models based on listening rather than looking, on musical interaction rather than verbal communication. I will suggest that work in other fields may help to point the way towards such paradigms but that it cannot provide ready-made models for our adaptation. We need theories of music grounded in the phenomenology of sound; such theories can only be developed and tested through the application of ethnographic methods; and they need to ask similar questions of 'music' in very different environments. In other words, the new ethnomusicology should also be the new new musicology. We Are All Ethnomusicologists Now Nicholas Cook (University of Southampton) It would be easy to represent the 'New' musicology as the transfer to the Western classical tradition of approaches and insights already commonplace in ethnomusicology; it didn't happen that way, though, and instead a great many wheels were reinvented. All the same, the result is a convergence of aims and assumptions perhaps greater than at any time since comparative musicology turned into ethnomusicology, a point I illustrate through discussion of (1) what Titon terms the 'new fieldwork' and (2) ongoing attempts to reconceive Western classical music as a perfoming art. If this reflects an increasing openness to ethnomusicological values on the part of traditional musicologists, it also reflects the undermining of once secure distinctions of 'self' and 'other' built into the definition of ethnomusicology: the result is the inclusiveness exemplified by Titon's definition of fieldwork as 'experiencing and understanding music'. My title, with its nod at Nathan Glazer's We are All Multiculturalists Now, expresses the obvious conclusion— except that I shall suggest that there might be an even more obvious one…. Intercultural Musicology - the way forward? Robert Mawuena Kwami (Institute of Education, University of London) Commentators such as John Blacking and Akin Euba have argued that the term ethnomusicology is inappropriate. Even if, as a discipline, the coverage of the 'beast' embraces Western pop and classical, jazz, and other Western musics, the term is flawed in several grounds. Some of these grounds will be explored, and it will be argued that 'intercultural musicology is a more suitable replacement, one that can accommodate all musicological studies and endeavours, and is more appropriate in and for a new millennium. Ethnomusicology Now and Soon: Some Assumptions on the Shape of Things to Come Jonathan P. J. Stock (University of Sheffield) Merriam identifies a series of assumptions (1964:37-39) that offer a convenient starting point for a consideration of the changes that might be either underway or on the way at present. Merriam proposed that ethnomusicology needed to become an objective science of human musical behaviour on the widest scale. A fusion of both field and laboratory research was required. So too was a clearer awareness of the need for research aims, and the better designing of fieldwork with these in mind. Without them, ethnomusicology amounted to no more than the unanalytical gathering of musical sound data or "armchair ethnomusicology", wherein commercial recordings are analysed by lab specialists with little knowledge of the broader musical scene. This paper produces its own set of assumptions about the state of this now muchly (yet still unevenly) theorised discipline. Specific attention is given to the following characteristics: music analysis (and its role as a tool that can critically interrogate fieldwork observations); criticism (and our role as expert commentators on individual musical performers, recordings or works); writing (and the questions of genre and voice); history (and the implications for the discipline of historical research); and comparison (and the role in the discipline of the broader frame of reference). E-fieldwork: a paradigm for the twenty-first century? Abigail Wood (Cambridge University) During the past decade, the incorporation of the Internet into daily life has had a huge impact in the Western world, changing the way we think about space, information and communication. The Net plays an increasing role in many aspects of music culture, from advertisement and vending via websites to discussion in newsgroups and the electronic distribution of music itself. With reference to my own research on contemporary Yiddish song, this paper will explore the various uses of the Internet by a dispersed community to discuss, promote and distribute its music. Via a case study of a vibrant online music community, the Jewish music discussion list hosted by shamash.org, I shall discuss the benefits and challenges of using online interaction, both as a participant and as a observer, in ethnomusicological research.