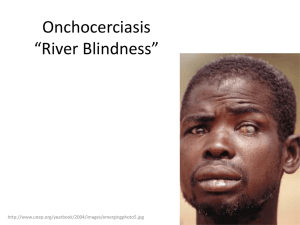

Onchocerciasis

advertisement

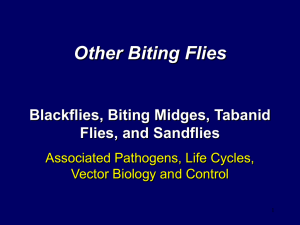

Nnenna Aguocha Human Biology 103 Parasites and Pestilence Dr. Scott Smith May 22, 2001 Onchocerciasis Introduction Onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness because of its most extreme manifestation, is caused by the parasitic nematode Onchocerca volvulus. Onchocerca volvulus, like various other blood and tissue-dwelling nematodes is a filarial parasite that thrives in the blood vascular system and tissues of humans as well as other vertebrate species. Filariae are long thread-like nematodes, or roundworms, that mature and mate in specific host tissues. Female adult worms produce eggs that after fertilization undergo several developmental stages to become elongated and worm-like in appearance. These modified eggs also known as microfilariae aggregate in the human lymphatic system, as well as in subcutaneous and deep connective tissues. These adaptations are critical for migration and survival in tissues where they can persist, without further development for extended periods of time. To become infective larvae, these microfilariae must first be ingested by an arthropod vector and inoculated into a suitable host when the vector takes a blood meal. For Ochocerciasis, the vector of transmission is the bite of a Simulium black fly, which thrives in rich, oxygenated water in rapidly flowing rivers and streams, hence the term- “river blindness.” Epidemiology Onchocerciasis, is the second leading cause of infectious blindness in the world. This disease, which also causes disfiguring skin disorders is endemic along fertile riverside areas in 36 countries in Africa, the Arabian peninsula, as well as countries in South and Central America including Mexico, Guatemala, Brazil, Venezuela, Ecuador and Colombia. The African and American forms of onchocerciasis exhibit different symptoms and characteristics, possibly due to the biting patterns of the vectors. In Colombia, the simuliid vectors for onchocerciasis are zoophilic with the result that in areas where large numbers of livestock are found, onchocerciasis affects domestic 1 livestocks. In areas where there are no large pockets of domestic livestock onchocercal infections in humans persist, thus suggesting a possible link between the abundance of domestic livestock and the prevalence of onchocerciasis in human populations. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that of the 120 million people worldwide who are at risk of contracting Onchocerciasis, 96% are in Africa. In addition, WHO also hypothesizes that of the estimated 18 million people worldwide who are infected with the disease, 99% reside in Africa. Among this infected population, Onchocerciasis has led to an estimated 270,000 cases of blindness and 500,000 cases of severe visual impairment. Although Onchocerciasis is most commonly associated with blindness, in reality, it is a chronic systemic illness that leads to extensive damage in the musculoskeletal tissue of infected individuals. In addition this disease leads to adverse changes in the immune systems of infected individuals, and in some areas of Africa, is closely associated with increased rates of epilepsy, weight loss and growth arrest. Although Onchocerciasis is endemic in several countries throughout the world, as a public health concern, it is most closely associated with Africa where it has debilitated populations, leaving over 25 million hectares of fertile land, capable of feeding 17 million people a year, inhospitable and uncultivable. Thus, Onchocerciasis transcends the category of a “public health concern” to emerge as a disease that constitutes not only a threat to health and well-being, but also a serious obstacle to socio-economic development in some of the world’s poorest areas. Classification And Taxonomy- attach image of worm with tree Scientific Name: Onchocerca volvulus Class: Secernenta Subclass: Spiruria Order: Spirurida Super family: Filarioidea Family: Onchocercidae Synonyms River Blindness River Eye Blindness History of Discovery 2 John O’Neill, a scientist in the Gold Coast studying a filarial parasitic infection known as “craw-craw,” or dermatitis, first observed the microfilariae of Onchocerca volvulus in 1875. Nearly twenty years later in 1893, Leuckart using samples collected and sent by missionaries from the Gold Coast first described the morphology of the adult worm. Although these discoveries were critical in identifying the morphology of the filarial parasite, scientists remained puzzled about the life cycle of the parasite as well as its transmission from person to person. This missing link was finally provided in 1915 by Robles who discovered the presence of onchocerciasis among coffee plantation workers in Guatemala, possibly introduced to endemic areas of Latin Americas as a result of the slave trade. He noted that laborers who resided outside the disease zone, and entered endemic areas only during the day to work, became infected with onchocerciasis. Using these case studies, he hypothesized that the vector of the disease was a day-biting insect, and more specifically, two anthropohilic species of Simulium flies found in the endemic areas. Although Robles conveyed his assumptions to his colleagues, he failed to carry out investigations to verify his hypothesis. Eleven years later in 1926, Blacklock, working in Africa, picked up where Robles had left off and demonstrated that Simulium black flies were indeed the vectors of transmission for onchocerciasis, by conducting a series of experiments using infected patients and Simulium damnosum flies. Females Simulium black flies seek blood meals after mating, and thus ingest microfilariae if the meal is taken from an individual infected with onchocerciasis. Thus, Blacklock collected several wild Simulium damnosum flies and proceeded to infect them by placing the within close proximity of infected individuals. He then proceeded to trace the development of the parasite in the gut, thorax, head and proboscis of the flies thus providing the final piece of the puzzle for the life cycle of the disease. These early discoveries laid the foundation for later discoveries, and in 1946, Hissette working in the Congo finally linked onchocerciasis with blindness even though Ghanaians living along the Red Volta River had long associated the biting flies with skin lesions and blindness. These ground breaking discoveries led to more investigations into the distribution of vector species as well as the transmission patterns and possible characteristic symptoms of various strains of the disease. Today, many lines of evidence 3 suggest that there at least two trains of Onchocerca volvulus- a savanna strain and a forest train. The savanna strain is more common in the woodlands and savannas of West Africa and is presumed to be the strain that induces the most serious cases of ocular pathology and blindness. The latter strain, or forest strain is endemic in the West African rain forest, and scientists have noted that endemic areas within these regions have more cases of hyperpigmentation and other skin diseases related to onchocerciasis. These observations have been confirmed in recent years with the advent of new technological systems that have allowed scientists to utilize DNA probes to prove the existence of two virulent strains of the disease. Vector There are six sibling species of the black fly species complex Simulium damnosum sensu lato that are capable of transmitting onchocerciasis. These vectors can be found in 30 sub-Saharan African countries, Yemen and six countries in Central and South America including Mexico, Guatemala, Brazil, Venezuela, Ecuador and Colombia. Two of these sibling species, S sirbanum and S damnosum sensu stricto, are the primary vectors in the African savanna, and two, S yahense and S squamosum, are the primary vectors in rain forests. All fur of these species conglomerate in certain endemic areas to from transition zones where intermediate disease patterns exist, and where the rate of blindness falls halfway between the rates of prevalence for the two strains. The final two vectors, S leonense and S anctipauli have restricted distributions. S leonense is found primarily in the lowlands of Sierra Leone while the latter species is restricted to the large coastal rivers of West Africa. Transmission and Incubation Onchocerciasis is transmitted from person to person through the bite of an infected black fly. This fly specie lays its eggs in rich oxygenated water, typically fastflowing streams and rivers. These eggs then undergo various developmental processes with adult forms emerging after a period of 8-12 days. These adult flies can live for up to 4 four weeks, during which time they can travel hundreds of kilometers in flight to reach areas that are suitable for mating and reproduction. Once mating has occurred, the female black fly must ingest a blood meal to acquire nutrients necessary for egg development. If the blood meal is taken from a person infected with onchocerciasis, microfilariae are also ingested along with blood. Microfilariae that survive this uptake and escape the peritropic membrane that forms around the blood meal penetrate the midgut and move into the flight muscles of the fly. After 28 hours, the microfilariae begin to differentiate into L1 larvae, and by 96 hours they molt and enter the L2 larva stage. The second molting process occurs by day 7, and after this, the L3 or infective larva travels to the head of the insect as well as other areas of the black fly. The infective larvae that succeed in finding their way to the proboscis of the fly enter the skin of an individual when the insect takes its next blood meal. The infective larvae that survive this stage of inoculation into the host begin to molt into the L4 stage within seven days, and by 1-3 months the worms complete differentiation into male or female adult species. Once maturity is complete, adult worms mate and female species begin to produce as many as 1300-1900 microfilariae a day. This daily production can continue for up to fourteen years depending on how long the worm persists in the human host, and microfilariae may live in the host for up to two years. Adult worms of Onchocerca volvulus have a propensity to congregate over bony prominences and thus become encapsulated in a fibrous, tumor-like mass or nodules that usually appear around the pelvic area and the skull within a year after infection, depending on the biting habits of the vector. For instance, in Venezuela and Africa mot nodules are located on the patient’s trunk or limbs, with a few nodules forming on the head. In Mexico and Guatemala however, nodules are frequently seen on a patient’s scalp and appear less often in other parts of the body. These nodules range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter and serve as the site of release for microfilariae. From these release points microfilariae travel mainly to the skin and they eyes of the infected host. In the skin, they are found predominantly in the lymphatics of the sub epidermis. In the eye, most microfilariae aggregate in the anterior chamber, the retina and the optic nerve. When a Simulium fly bites an infected individual to take a 5 blood meal, microfilariae in the skin are ingested along with the blood meal and thus perpetuate the life cycle of the parasite. Morphology Adult worms are white, long and thread-like. They are typically knotted together in pairs in the subcutaneous tissue and are characteristically slender and blunt at both ends. Female adult worms may be as long as 50cm in length and as thick as 0.5mm in diameter. The male adult worms are shorter and typically measure no more than 5cm in length and 2.2mm in diameter. These worms typically lack lips and buccal capsules but display two circles of four papillae around the mouth; the esophagus lacks conspicuous divisions. In females, the vulva lies behind the posterior end of the esophagus, and in males the tail is a curled ventrad that lacks alae. Microfilariae of this parasite are unsheathed and typically measure 250-300 microns in length. Reservoir Although there are zoophilic forms of onchocerciasis, there are no known reservoirs of the strains that affect humans. Clinical Manifestations The predominant symptoms associated with onchocerciasis are rashes, lesions, and nodules over bony areas, blindness and severe visual impairment, intense itching and hyper-pigmentation, and lymphadenitis, which lead to hanging groins and elephantiasis of the genitals. Other symptoms in certain endemic areas of Africa include epilepsy, growth arrest and general malaise and debilitation. These clinical manifestations of the disease begin to appear within one to three years after the injection of the infected larvae and are almost entirely de to localized host inflammatory responses to dead or dying microfilariae. These immune responses are typically antibody and cell mediated responses. The strength of the immune response varies from person to person depending on the length of exposure to antigens as well as the regulating activities of the host. Eosinophils are typically found around the nodules that encapsulate adult worms and are critical in the inflammatory response of the host. Microfilariae migrating in the skin typically destroy elastic tissue over a period of years, thus causing the formation of redundant folds in the host. Skin lesions are the most pervasive consequences of 6 onchocerciasis. In surveys conducted in seven endemic areas in five African countries, 40% to 50% of all adults surveyed reported severe itching. Thus, in its mildest form onchocerciasis manifests as a localized musculopapular rash. These reactive lesions and itching sometimes clear up within months without treatment. In more severe cases of itching edemas occurs as well as chronic papular dermatitis, and lichenified, hyperkeratoic lesions which often heal with hyper pigmentation. Lesions of the eye typically take several years to develop and occur mostly in individuals over the age of 40. In the eye, microfilariae migrate along sheaths of the ciliary vessels and nerves from under the bulbar conjunctiva directly into the cornea, through nutrient vessels present in the optic nerve. Invasion of the cornea by microfilariae leads to the inflammation of the sclera, or white of the eye, followed by an invasion of fibrous tissue. This leads to extensive vascularization of the cornea, and thus, severely impairs the vision of the host. Subsequent invasions and immune responses frequently lead to complete blindness. Microfilariae can also wreak havoc in the lymphatic system of the host. The lymphatic system is responsible for removing foreign substances from distal skin regions; however, with the invasion of microfilariae into this system, this function is severely compromised leading general inflammation in regions distal to the lymph nodes as well as a loss of elasticity and the creation of protruding lymph glands enfolded in hanging pockets of skin. This condition, prominent around in the pelvic region of the host, is called the “hanging groin effect,” and may be classified as minor elephantiasis in severe cases. 7 Diagnostic Tests Onchocerciasis can be diagnosed by observing skin snips taken from the shoulder and other areas of infected individuals. These snips are then immersed in saline solution and observed under a microscope for the presence of emerging microfilariae. Another method that is utilized when microfilariae cannot be observed is the administration of 6mg of diethylcarbamazine (DEC). This test is known as the Mazotti test, and results in itching as well as severe inflammation where microfilariae are present. Because of the severe side effects associated with the Mazotti test, health care workers have opted to use less invasive alternative methods such as searching for signs of nodules in areas where onchocerciasis is prevalent, and using slit lamps to detect microfilariae in the cornea and anterior chamber of the eye. Other alternative methods include polymerase chain amplification of parasite DNA and recombinant antigen-based immunoassays, which are utilized for individual diagnosis and confirmation in some cases. Management And Therapy Public Health and Prevention Strategies Useful Links References Before the 1980s, the only available method for control of onchocerciasis was elimination of black fly vector populations. This strategy was used with considerable success in The Onchocerciasis Control Program in West Africa (OCP). The discovery of ivermectin, the first effective drug suitable for mass treatment of onchocerciasis, has revived International interest not only in fundamental research but also in development of new strategies to control onchocerciasis in the countries outside the OCP area. This report 8 gives an overview of current parasitological, clinical, epidemiological and diagnostic data about onchocerciasis. Although little is known about the early development of Onchocerca volvulus in the human host, significant insight has been gained into the population dynamics of the parasite. The pathogenesis of cutaneous and ocular manifestations in onchocerciasis is now better understood. Epidemiological studies are under way to evaluate the extent of systemic manifestations. Recently developed diagnostic methods are more sensitive than conventional parasitological techniques. A new method for rapid assessment of endemic level has provided a detailed picture of the distribution of onchocerciasis. Species- and strain-specific DNA probes have been developed for identification of parasites in West Africa. New methods for quantifying disability allow evaluation of the socio-economic impact of the cutaneous and ocular complications of onchocerciasis. 9