Psychoanalysis Psychoanalysis originates with the ideas of

advertisement

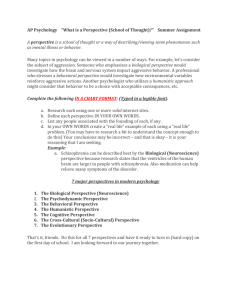

Psychoanalysis Psychoanalysis originates with the ideas of Sigmund Freud, an Austrian physician, in the 1890s. It is a method of studying why we behave the way we do, and the psychological processes behind our thoughts and actions. “Psychoanalysis” is a very broad term, and many different theories have developed from the roots of Freud’s work. Many techniques have very different approaches, though they all technically fall under the blanket term “psychoanalysis.” The original Freudian psychoanalysis is a kind of treatment in which the patient talks about his or her feelings, dreams, and fantasies. This is where we get the famous image of the patient lying on the doctor’s couch. Freud encouraged patients to “free associate,” or attempt to speak and make connections between ideas without censoring themselves or thinking much about what they were saying. He urged this technique as a way to try to get at the underlying causes of their psychological conflict. In Freudian psychoanalysis, the patient talks and then the doctor interprets what the patient has said, and analyzes their dreams and fantasies based on Freudian theories. This is different than modern-day psychotherapy, in which patients are encouraged to come to their own conclusions, with the guidance of the counselor. Many of Freud’s theories involved sexuality, and practitioners of psychoanalysis often trace their patients issues back to the sexual stages of development. In addition to analyzing, part of the process of psychoanalysis is an attempt, on the part of the doctor, to get the patient to confront feelings of guilt, and get through whatever psychological defenses the patient has put up. One of the main ideas in psychoanalytic theory is that of transference. Transference is when a person unconsciously redirects feelings for one person (such as their mother) to another (such as their spouse), or redirects emotions about an event (such as a childhood trauma) to other areas of their life. Another important idea in psychoanalysis and Freudian theory is that of the id (our basic desires and instincts), the superego (our moral conscience) and the ego (the reality principle). As we develop, these three elements interplay. In a healthy person, according to Freud, the ego is the strongest so that it can satisfy the needs of the id, not upset the superego, and still take into consideration the reality of every situation. (Freud's Structural and Topographical Models of Personality, 2009) Psychoanalysis is not limited to Freud, however. It continues today, though many modern psychoanalysts have departed from Freud’s theories to some degree (for example, his theories on female sexuality have been almost universally discredited). In 2000, there were approximately 35 training institutes for psychoanalysis in the United States. Behaviorism Behaviorism is the psychological theory that everything humans and animals do, including thinking and feeling, can be considered a behavior and measured as such. It can be broken down into two basic ideas. The first is that psychology is the science of behavior, not the science of mind. Any psychological theory, according to behaviorism, should be able to be measured by observation in order to be valid. The second main idea is that behavior can be described and explained without referencing mental events or internal psychological processes. The sources of behavior are external (in the environment), not internal (in the mind). According to behaviorists, hypothetical constructs such as ‘the mind’ (independent from what can be physically measured in the brain) should not be taken into account. (Behaviorism, 2007) The main people behind behaviorism were BF Skinner (who conducted research on operant conditioning, or the use of consequences to modify behavior), Ivan Pavlov (who did similar work with classical conditioning), and Edward Thorndike, and John Watson (both of who worked to restrict psychology to experimental methods). Behaviorism was the leading method of psychological investigation in the 19th century and into the 20th century, but it began to be replaced in the second half of the 20th century with the rise of the cognitive revolution. (Behaviorism, 2007) Humanism Humanism, when applied to psychology, is a perspective that emphasizes the study of the whole person (in contrast to behaviorism, for example, which only looks at observable behavior). Some might argue that humanistic psychology is less scientific, because it attempts to look at human behavior not only through the eyes of the observer, but through the eyes of the person doing the behaving. Obviously, this is difficult to measure, and impossible to be objective about (since the whole point is the individuals subjective experience). But humanistic psychologists believe that taking a holistic approach to psychology is the only way to reach complete and meaningful conclusions. (Humanistic Psychology Overview, 2001) Humanistic psychologists maintain that humans are not just the product of their environment, as behaviorists claimed. In fact, they see behaviorism as a sort of biological reductionism, in which human beings are reduced to only their physical parts. They also don’t believe that humans are controlled by their unconscious, as psychoanalysis suggests. According to the Association for Humanistic Psychology, neither previous psychological movement acknowledged that it was possible to study values, intentions and meaning as important elements in our conscious existence. This is what Humanistic Psychology attempts to do. The humanistic view of human behavior is described by the Association for Humanistic Psychology as “a value orientation that holds a hopeful, constructive view of human beings and of their substantial capacity to be self-determining” and believes that “intentionality and ethical values are strong psychological forces, among the basic determinants of human behavior” (Humanistic Psychology Overview, 2001). Choice, creativity, and the interaction of the body, mind and spirit are all emphasized in humanistic psychology. Sources Association for Humanistic Psychology. 2001. Humanistic Psychology Overview. Retrieved from: http://www.ahpweb.org/aboutahp/whatis.html Freud, S. & Strachey, J. (1989). An Outline of Psycho-analysis. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. (2007, July). Behaviorism. Retrieved from: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/behaviorism/ All-Psych Online. (2009). Freud's Structural and Topographical Models of Personality. Retrieved from: http://allpsych.com/psychology101/ego.html.