The Place of Moral and Civic Values in Recent Educational Reform

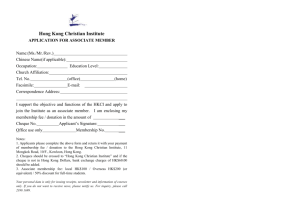

advertisement

Values Education in Hong Kong: Development and Perspectives Wing On Lee Hong Kong Institute of Education Presented at the Values Education National Forum, 2-3 May 2005, Canberra. Ladies and Gentlemen, thank you very much for giving me an opportunity and honour to share with you in this forum about the situation of Hong Kong. I have to say what I am going to share only represent my own interpretations, but these interpretations were generated from my participation in this area of work on many circumstances over the last ten years. Over the last decade, I participated in the IEA Civic Education Study as the Hong Kong representative and also a member of the international steering committee, and many other international studies on citizenship education and values education. At the level of community involvement, I have also participated in drafting the Guidelines on Civic Education in Schools 1996 and the Civic Education Junior Secondary syllabus. I have been involved in several aspects in educational reform in Hong Kong as a member of the Curriculum Development Council, and have been a member of semi-governmental Committee on the Promotion of Civic Education. I have to say, the sharing this morning is a combination of both my participation experiences in values education development and reflections on those experiences as an academic. I do need to make a note at the beginning that civics, moral and values are really interrelated, at least in the Asian context, and I cannot entirely distinguish them from one another in the process of sharing. Debates before 1997: Nationalism versus Liberalism As 1997 came closer, there were more calls for change in the curriculum to reflect Chinese sovereignty in Hong Kong. Moreover, there were more and more calls for strengthening the preparation of the re-identified Chinese citizenry of Hong Kong. In 1994, the cultural subgroup of the Preparatory Working Committee for handover openly declared that: Civic education had been under-emphasized in Hong Kong, and, therefore, nationalism and patriotism had been under-valued; Following the resumption of Chinese sovereignty, civic education in Hong Kong should aim at building nationalism and patriotism; Education in the transitional period should strengthen learning in Geography and Chinese History, as well as the Basic Law; and, The Education Department should facilitate the development of civic education as a formal subject in primary and secondary schools (Ta Kung Pao, 13 September 1994). The government responded by setting up an ad hoc working group to review the Civic Education Guidelines. The task of the ad hoc group was actually more than a review of past Civic Education Guidelines. Instead, it soon became clear that it had been appointed to draft new Civic Education Guidelines that could transit across 1997. This made the whole venture extremely political. Being aware of the political sensitivity of such a task, the government appointed members who could represent a spread of interests and 1 political views. Moreover, the drafting process was made known to the public as far as possible. A representative of the group was assigned to meet with reporters after each meeting, reporting the main points of discussion. The drafting process therefore enhanced the possibility of public “participation”, since people, being informed of the progress, had an opportunity to put forth their views so as to influence the direction of the Guidelines. At the same time, this strategy triggered heated debates on what the direction of Hong Kong civic education should be. The most outstanding debates emerging during the period of Guidelines’ preparation was that of nationalistic/patriotic education versus human rights/democracy education. Interestingly, neither government spokespersons nor appointed members of the working group suggested that student opinion should be gauged or that such an exercise would, itself, be a valuable form of civic education. In shaping the direction of new Civic Education Guidelines, the PWC’s cultural subgroup openly proposed that civic education after 1997 should be adjusted in order to introduce and popularise the Basic Law and to enhance students’ understanding of Chinese history and culture so as to strengthen nationalism, national identity and national pride among students. A member of the committee, S.K. Lau, also openly expressed that: The emphasis of civic education after 1997 should be placed on two respects. First is the strengthening of the concept of country and the sense of belonging to the country and nation. Second is the introduction of the Basic Law…. Although democracy, human rights and environmental education are also quite important, they are not urgent for 1997 (Wen Wei Po, 22 May 1995). Few of the proposals for a nationalistic and patriotic focus in civic education were mentioned without also touching upon democracy and human rights. However, an alleged over-emphasis on nationalism and patriotism, mixed with anti-colonial sentiments, aroused much concern and angry responses in public discussions. There were people expressing entirely opposite view. For example, Choi (1995) reacted first, by distinguishing national education from civic education. She considered that the purpose of civic education was to develop critical thinking for political participation, whereas nationalist education was a kind of irrational or, at least, non-rational identification with the nation. Man (1995) also elleged in her, entitled “Poor Civic Education Philosophy - A Critique of Education Convergence’s ‘Opinions on Civic Education’”, that the equation “civic education = national education = political education” is over-simplistic, because even though that equation could be accepted, we still need to ask what the nature of ‘politics’ is: Of course, national education includes politics. But what kind of ‘politics’ do you refer to? Should education not leave [sic] the kind of ‘politics’ that allows freedom of expression and participation? Or should we restrict ourselves to the ‘political’ activities defined by the ruling party? We cannot have answers from their opinion paper. But from the explanation in the opinion paper,… ‘politics’ cannot transcend the level of ‘political entity’. In other words, if ‘politics’ is defined by a political entity that suppresses citizens (through unjust constitution and laws), we do not need to mention any personal freedom of expression and participation. 2 The 1996 Guidelines on Civic Education for Schools: Sanctity of Life as the Starting Point for Civics A major characteristic of the 1996 Guidelines is the inclusion of a chapter on conceptual framework. This chapter identified three dimensions of civic education. First was the values dimension. The Guidelines argued that common good is based on individual good. It started with an affirmation of the sanctity of life and further argued that such an affirmation set the ground for human dignity and respect, and other related human values like equality and justice. Grounded on the endorsement of such values as human dignity, equality and justice, the Guidelines spelled out the need to develop a social system, which observes human rights and democracy. Moreover, based on a view that individual and common good are interdependent, the Guidelines proposed a complementary view of collectivism and individualism. A second dimension was the concept of the locality context in civic learning. The Guidelines argued that civic education cannot take place in vacuo, but only in a certain locality context, extending from family, to neighbouring community, regional community, national community, all the way to the international community. The concept of locality context also built on the most intimate social relationship, which is brotherhood or sisterhood, and argued that the extension of the locality context meant the extension of brotherhood or sisterhood to a broader level of human relationship. Thus, the concept of neighbourhood applied to the neighbouring community, regionhood to the regional community, nationhood to the national community, and humanhood to the international community. The concept of locality context provided a background for the integration of two concepts of citizenship in the document, i.e. social citizenship and political citizenship. The emphasis on the extension of locality contexts related to the concept of social citizenship, as it meant the broadening of social relationships. On the other hand, the locality context device also provided the Guidelines with an opportunity to discuss political citizenship in the context of the national community. The Guidelines argued that discussions on nationalism and patriotism in relation to the locality context were more sensible and appropriate than campaigns to secure for them the major or even the only part of civic education. Placing national community adjacent to the other communities, such as the regional community and the international community meant that the civic learner should not only be aware of the significance of the nation, but also the region and other parts of the world. Proponents of the new approach argued that being aware of the region was significant for Hong Kong citizens, as Hong Kong was going to be a Special Administrative Region. Similarly, they claimed that being aware of other parts of the world was also important as Hong Kong has strong international relationships. The broad perspective of citizenship was more elaborately expressed in its third dimension, i.e. the dimension of civic experience. The Guidelines further argued that an individual’s civic competence, attitudes and beliefs were significantly related to his/her civic experience. The Guidelines also called attention to the existence of a variety of civic agents in society, such as political associations, social and welfare organisations, 3 cultural organisations, religious organisations and schools, all of which could affect an individual’s civic experience. In the context of educational experience, the Guidelines particularly called on schools to re-examine their school ethos. They were asked to consider whether, in actual practice, they were democratic or not, whether they upheld justice or not, and whether they respected human rights or not. In an effort to pierce through the various dimensions, the Guidelines proposed a studentcentred approach to civic education. According to this, one of the major purposes of civic education, in addition to those of nationalism and patriotism, was to develop critical thinking abilities. Consequently, the teaching and learning processes needed to emphasize reflection and action (Lee & Sweeting, 2001; Education Department, 1996). Struggles after 1997: Localisation/Nationalisation versus Globalisation One of the major feature of post-1997 Hong Kong is its educational reform. The Learning to Learn document suggested that the learning to learn (i.e. effective learning) target is to be achieved through four key learning tasks, namely: moral and civic education: to help students establish their values and attitudes, reading: to learn broadly with appropriate strategies to learn more effectively, project learning: to develop generic skills, acquire and build knowledge, and information technology: for interactive learning. The Curriculum Development Council further published a series of curriculum guides in 2002. In the moral and civic education curriculum guide, five priority values were proposed, namely perseverance, respect for others, responsibility, national identity and commitment. The Guide stipulated that: These priority values and attitudes are proposed with due consideration given to students’ personal and social development and to the changes in the local context … and global context, with a view to preparing our students to meet the challenges of the 21st century. The values are interconnected and if fostered, should help students to become informed and responsible citizens committed to the well-being of their fellow humans (CDC, 2002a, p. 2). Nationalisation It is obvious that national identity is propounded as one of the priority values in the new curriculum, and when elaborating on this particularly value, the Guide says: The return of Hong Kong to China since 1997 calls for a deeper understanding of the history and culture of our motherland. There is a need to strengthen the sense of national identity among our young people. It is imperative to enhance their interests in and concern for the development of today’s China through involving them in different learning experiences and lifewide learning. Instead of imposing national sentiments on them, we must provide more opportunities for young people to develop a sense of belonging to China (ibid., p. 3). In addition to revision in citizenship curriculum, the government has also made efforts to 4 enforce national identity education in a wide spectrum of areas. Law (2004) comments that the Chinese Hong Kong government has politicised the school curriculum by enhancing the public’s understanding of China and Chinese culture and strengthening their sense of belonging. This was a clear contrast to the former government’s policy of depoliticisation, delocalisation and deaffiliation from the Chinese mainland in the eighties. Moreover, obvious measures were adopted to develop a “new national identity”, in geographic, cultural, language and political terms. Geographically, massive student visits to the mainland have been organised. Many of them were organised by individual schools out of their own initiatives, but many others were also subsidised by the government in one way of another, such as from projects approved by the Quality Education Fund. In July 2004, the Education and Manpower Branch (2004b) launched a high profile national education programme as a part of the youth leadership award scheme. The 11-day programme, held in Beijing, enrolled 170 student leaders from local school. The programme covered a series of lectures and visits, introducing to the participants the Chinese government structure, culture and major achievements, including visits to major historical sites. The government also began to subsidise staff and principal training undertaken by major institutions in the mainland, such as East China Normal Universities, Beijing Normal University, and Guangdong College of Education. Culturally, as the above documentary analysis has shown, there were deliberate additions of China elements in the post-1997 curricula, and many of them are focused on introducing Chinese culture. The above-mentioned Report on China Element (1998) mentioned that Chinese elements have permeated over 100 syllabi of over 40 school subjects. Moreover, Chinese history and cultural are specifically designated as core elements of learning in the personal, social and humanities education key learning area. In school, extracurricular activities relatedto Chinese culture have also been intensified, such as Chinese orchestras and bands, Chinese dance clubs, and kung fu classes (Law, 2004, p. 266). Globalisation As mentioned above, Education Commission’s (2000) Learning for Life, Learning through Life attempted to justify its reform initiatives in the globalization context, in the sense that needs to re-orientate its education to face changes brought about by the emergence of the knowledge-based economy and global economy. In this context, it is essential for Hong Kong to nurture the younger generation of global awareness, and to develop a host of skills adaptable to this changing world. The document says: The world is undergoing fundamental economic, technological, social and cultural changes. The world economy is in the midst of a radical transformation, and the industrial economy is gradually being replaced by the knowledge-based economy…. Rapid developments in information technology have removed the boundaries and territorial constraints for trade, finance, transport and communication. As communication links become globalised, competition is also globalised (Education Commission, 2000, pp. 27-28). 5 While the above section demonstrates concerns for national identity elements in the process of curriculum reform in Hong Kong, it is interesting to note that major justifications for curriculum review and the subsequent current reform proposals are related to challenges from globalization. For example, the Curriculum Development Council’s Learning to Learn document is prefaced by a strong reference to the need of developing global awareness. In its opening paragraph of the first chapter, the Chairman of the Curriculum Development Council says: To cope with the challenges of the 21st Century, education in Hong Kong must keep abreast of the global trends and students have to empower themselves to learn beyond the confines of the classroom. The school curriculum, apart from helping students to acquire the necessary knowledge, should also help the younger generation to develop a global outlook, to learn how to learn and to master lifelong skills that can be used outside schools (CDC, 2001). This view is repeated in the summary that precedes the contents of the document: The Curriculum Development Council (CDC) has conducted a holistic review of the school curriculum during 1999 and 2000 in order to offer a quality school curriculum that helps students meet the challenges of a knowledge-based, interdependent and changing society, as well as globalisation, fast technological, and a competitive economy (ibid, p. i). Moreover, among the various generic skills proposed to be developed in the new curriculum, many of them are generally classified as citizenship skills, such as collaborative skills, communication skills, critical thinking skills and problem-solving skills. Interestingly, of the values and attitudes advocated to be developed through the new curriculum, as tabled in the document (Appendix II), many of them are global citizenship values, such as plurality, democracy, freedom and liberty, common will, tolerance, equal opportunities, human rights and responsibility,… etc. Of the 80 values tabled in the appendix, only a handful of them were related to national identity, namely patriotism, culture and civilization, heritage and sense of belonging (ibid., p. II-2). Referring to specific subject areas, in primary school, global awareness was mentioned as much as national identity. The core elements of Strand 6, “Global Understanding and the Information Era”, include the following topics: Characteristics of people of different cultures Cultural differences which affect the lives of different peoples The ways we perceive other cultural groups Respecting cultural differences Ways people interact with other cultural groups Reasons for people to exchange information, goods and services Ways that people in the world are linked How Hong Kong and China are related to the regions around them Common elements found in different cultures Influences of the physical environment and social conditions on cultural developments of the world 6 Effects of cultural interaction on cultures and societies The effect of major historical events Major current international events The interdependence of different parts of the world Communicating using IT tools with people in different parts of the world Moreover, for Primary 4 to 6, the Curriculum Development Council has identified some areas for inclusion of global citizenship education elements. For example, for Primary 4, there was a theme called “Wonderful World”, while the relevant unit is “Children in other Parts of the World”; for Primary 5, there was a theme on “Life in the City”, and the unit was “Physical, Environment, Technology, and Culture”. For Primary 6, there was a theme called “Global Perspective”, and the relevant unit was “Introduction to Common Issues of Concern”. The 1998 junior secondary Civic Education syllabus also covered global citizenship, as one of the six themes of the subject (family, neighbouring community, regional community, national community, international community and civic quality and civil society). Specific topics that covered global citizenship are listed in Table 1. Table 1 Global Citizenship Topics in the Civic Education Syllabus, 1998 Level Secondary 1 Secondary 2 Secondary 3 Topic 1. The pluralistic world 2. Global citizenship 1. The heritage of human civilization 2. Significant historical events in the world 1. Major global issues Personal, Social and Humanities Education, a Key Learning Area emerged in the curriculum reform, has been identified as closely linked to civic education. It did not only include elements of national identity education, but also global education. The curriculum guide (CDC, 2002b) introduced a seed project that involved seven secondary schools conducted during 2000/1. Three of these seven schools adopted the framework of eccentric circle of citizenship concern, developing from the individual to society, country, and the world. They aimed at a balanced understanding of the local and national communities as well as the global community. The topics/activities covered in these projects included: Secondary 1: discuss current events, including those important local, national and international news. Secondary 2: discuss recent developments in China, the relationship between China and the world, and the interdependence between Hong Kong and the Mainland. 7 Secondary 3: McDonald and the global village, globalization and interdependence, cultural exchange, poverty, war and peace, technology and human society, economic ethics, living in the interdependent world. The government introduced a new subject called Integrated Humanities in 2003 in senior secondary schools. Its curriculum guide stated that the aim of the subject was to widen students’ perspectives, helping students know more and care about the world, understand the process of globalisation and providing multiple perspectives to think about controversial issues. Integrated Humanities has specific topics on globalization and environment issues, as shown in Table 2. Table 2 Topics Related to Global Citizenship in Integrated Humanities Unit Questions Globalisation 1. What is globalization? 2. What are the influences of globalization? 3. Will globalization brings more conflict or peace? The 1. What are the problems we face in our environment and relationship ecology? between 2. What different values and considerations is environment humans and protection grounded upon? the 3. What are the practical problems in implementing environmental environment protection? In 2003, Oxfam Hong Kong conducted a comparative study of global citizenship education in secondary schools in Hong Kong and Shanghai. The study examined the Hong Kong curriculum and found that global issues penetrated the curriculum in various subjects. In general, Hong Kong teachers thought that it was important to raise the global awareness of Hong Kong students, but at the same time they were not content with the degree of emphasis in their schools. Compared to the Shanghai teachers, Hong Kong teachers were more concerned with the value dimension of global citizenship, particularly in their concern for war and peace and regional poverty. Whereas teachers in Shanghai were more concerned about competitiveness of their students in the global world. Moreover, Hong Kong were concerned about the development of critical thinking among students as a part of global citizenship education, which is in line with the emphasis of the generic skills mentioned in the curriculum reform documents (Lee and Gu, 2004, pp. 96-103). Values of the Individuals Examination of the various values studies in Hong Kong would find a diverse picture. However, most of these studies can be summarized into an exploration of the status of traditional oriental/Confucian values in the place of the modern society, in terms of orientations towards family, group, nation versus self and achievement orientations. However, these study also show that these values cannot be dichomotmized. For example, when finding a higher emphasis on self-oriented values in the Chinese 8 Language textbooks, both Au and Leung argued that this rather reflected a Chinese traditional emphasis on self as a starting point for social relationships. For example, Au (1995, p. 194) argues: “Self-cultivation” is the foundation of being a human, and the fundamental requirement of attaining order and harmony of human relationships. “Selfcultivation” stimulates “self-reflection”, “self-critique”, “seeking one’s own self” and “seeking one’s truthfulness” from “self-awareness” to “self-love” and “self-control”. All this should go further to attain self-determination, [a high degree of] cultivating oneself, self-enrichment, and to attain the four virtues of “benevolence, righteousness, rite and intelligence. The past studies have revealed that we need an on-going reflection upon what we mean by traditional values and modern values, and how they are distinguished and integrated to be meaningful to a population who has inherited certain traditional values but needs to cope with the demands of a modern society. In 1997, I participated in a comparative sigma study on values of the educational leaders. We interviewed 40 leaders in Hong Kong. The result shows that the Hong Kong respondents have consistently placed high significance on attributes essential for the development of personal quality, with an expectation of extending awareness from a personal level to the social/national and global levels. Our respondents in general view that the person, the nation and the community are interrelated with one another, and more than that, the extension of concern to the community is viewed as a stepping stone towards the development of an international perspective. Such a continuum resembles the Confucian idioms as “Extending yourself towards the others” and “Cultivate yourself, regulate your family, administer your country, and in the end pacify the world.” Concerning the items that received lower priority in the survey, such as “to promote world peace”, “to combat juvenile delinquency”, and “to improve respect and opportunities for girls and women”, our respondents defended that they should not be viewed as not important. However, among all the listed reasons, they would regard that capacity building is more important in values education, and therefore they chose those reasons that have close relationship to the enhancing of personal quality. Further examining those personal quality, the choice of the Hong Kong respondents are quite well rounded and balanced, in choosing “spiritual development”, “reflective and autonomous personality”, and “sense of individual responsibility” as the top three reasons. There is emphasis on autonomy and responsibility, as well as spirituality and reflectivity. In view of the continuum we have identified, i.e. extending from a concern for personal quality to a conern for community, nation and the world, a philosophy of values tends to emerge. The philosophy is characterized by a balanced concern for spirituality and rationality, autonomy and responsibility, as well as self and the collectivity. However, it is interesting to note that the quality of the self has become the centre of concern (Lee, 2001). Interviews with the Hong Kong educational leaders seem to provide some clues. According to them, building moral and spiritual values is intrinsically important for the 9 youngsters in their development because, as many of them said, “Their intrinsic values determine the directions of their development.” Also, helping the young develop reflective thinking and autonomous personalities are important for them to make wise decisions in their development. It seems likely that in the Eastern eyes, spirituality is referred to the internal qualities of the self that provides a parameter for the self to make wise decisions, with rational tools such as reflective thinking and autonomous personality. Such an axis is fundamentally important for processing rational thinking and making rational choices. In fact, this is what the study of value should mean. Axiology, i.e. the study of values, starts with an axis, and this axis is the fundamental direction of the self. When the Chinese language talks about self-cultivation (xiushen), self-reflection (zixing), self-discipline (zilu), taking it upon oneself (ziren), getting it by, or for, oneself (zide), self-enjoyment (ziqian) etc., all this forms the fundamental axis for one’s thinking and choices. If self means auto, an autonomous person in the Confucian tradition contains all these qualities. To de Bary (1983, p. 65), this is what a neo-Confucian autonomous mind should possess: self consciousness, critical awareness, creative thought, independent effort and judgment (Lee, 2004a). If moral values refer to a more personal dimension than civics, the Hong Kong choice represents a more consistent progression of the continuum from the personal dimension to the social dimension of values, which is consistent with what we have found from the previous section on reasons for values education. Moreover, it is very clear that in Hong Kong, the respondents place priority on character and moral education over political education. Conclusion Tensions of the government Hong Kong adopts the social and economic perspective in its justification for the need to face globalisation challenges in its curriculum development. It is worth reiterating that although national identity is one of the four key elements of education, the major skills to be developed in its curriculum reform, i.e. the nine generic skills are rather globalised. These skills (i.e. collaborative skills, communication skills, critical thinking skills and problem-solving skills) can be found almost in any country’s curriculum documentations as significant skills in facing global challenges. Hong Kong in this sense is quite ready to be integrated to the global world, attempting to develop skills in meeting the needs of the global challenges especially in the term of knowledge economy. The identification of global citizenship values, such as plurality, democracy, freedom and liberty, common will, tolerance, equal opportunities, human rights and responsibility as shown in the analysis above is another illustration of adopting global values in the curriculum. The integration of these globally emphasised values and skills into the curriculum is regarded as so important that it is very much a kind of local choice. In this sense, the local response to the globalisation can be viewed as a kind of localised globalisation. Struggles of the populace 10 In respect to citizenship knowledge, Hong Kong students ranked among the top five in the international study. This is an exceptional finding for Hong Kong students both in terms of their political experience and home environment for study. In terms of political experience, the student respondents were brought up in a colonial system without experience of a democratic system. Moreover, there is very little, if not none, formal teaching about democracy in the curriculum. In terms of home environment for study, Hong Kong students in general do not possess as many books at home as their counterparts. However, rather than coming from government intentions or formal education channels, students “learned” about democracy and politics through the exposure towards political controversies in the process of political transition, and develop their aspirations towards democracy in the midst of political uncertainties towards the handover. Hong Kong students’ learning curve has risen very sharply and fast indeed. They have developed democracy aspirations that are very close to concepts of Western democracy. They have strong concerns for election and freedom of expression. They consistently accord a high rating on the significance of election and freedom of expression in the questionnaire, such as “the right to elect political leaders”, “votes in every election”, and “votes in national election” (which are all scored a mean above 3). In respect to freedom of expression, Hong Kong students strongly support “the right to express opinions freely and strongly oppose to the prohibition of criticism toward the government and newspapers being owned by one company. Moreover, in the classroom, they value the respect of teachers for them to express opinions, particularly views different from most of the other students. Hong Kong students are concerned about citizenship rights, such as political rights, social rights, economic rights and cultural rights. All rights-related items are accorded a mean above 3. This applies to all the items related to political, social and economic rights, and all the items related to the cultural rights of immigrants. However, Hong Kong students are ambiguous about women’s political rights. This reveals the perpetuation of gender stereotyping against women in Hong Kong, despite growing assumption of high positions by women in public offices. Such a phenomenon is also reported in other studies, not only in political, but also socio-economic participation (Cheung, Chun & Ngai, 1997, p. 229). Hong Kong students try to avoid confrontational and violent political actions. Whenever questions about protests and violent political actions are asked, Hong Kong students accord relatively low scores toward them, such as peaceful protest (mean=2.68), and collect signatures for a petition (mean=2.59), non-violent protest (mean=2.36), spray paint protest slogans (mean=1.65), block traffic (mean=1.61) and occupy public buildings (mean=1.59). It is obvious that students tend to say yes to non-violent protests (but not enthusiastically) and no to violent protests. Hong Kong students prefer social-related activities to politics-related activities. Items on social services and voluntary work tend to score higher than political activities, and social-related activities are scored higher than political activities (which are then scored 11 higher than protests). While Hong Kong students are interested in election, they are not quite interested in joining political parties. Also, Hong Kong students tend to trust the courts and police rather than political parties. Although Hong Kong students tend to support social-movement-related citizenship, their mean score for this scale (9.6) is much lower than the international mean, and is close to the bottom score. Perhaps this is due to an ambivalent attitude toward political activities. Hong Kong students do express love for Hong Kong and being proud of Hong Kong. However, like the above two categories, Hong Kong’s score in this respect is rather low when compared with those of their counterparts. A mean of 8.9 is very close to the bottom score of 8.4. Hong Kong is even among the countries with the lowest scores in this scale. Comparing Hong Kong with the other participating countries in the IEA Civic Education Study, three patterns emerge. The areas that Hong Kong score well above the international mean are civic knowledge and immigrant rights. The former reflects the education system of Hong Kong and the latter reflects a good representation of the immigrants in the school system. The areas that Hong Kong locates at the international average are conventional citizenship and trust towards government-related institutions. This reflects the Hong Kong populace is in general supportive of the government and prefer conventional citizenship to social-movement-related citizenship. Apart from these four areas, all other areas are accorded scores lower than the international average. In particular, economy-related government responsibilities, attitudes toward the nation, support for women’s political rights, confidence in participating in school and open classroom climate are quite close to the bottom score. Generally speaking, this reflects that the depolticised political environment of Hong Kong perpetuates beyond 1997 (Lee, 1996; Lui & Chiu, 2000, p. 16). This does not mean that students are negative towards politics and citizenship concerns, but a tendency to avoid activist politics. Apart from the IEA Civic Education, at least two other studies demonstrate this point. The first is a study conducted by the Committee on the Promotion of Civic Education in 2000. According to their survey, while 75% respondents agreed that active participation in social affairs is a duty of the citizens, 76% felt that individuals could not influence government policies, and only 14% felt that they understood the operation of the government (CPCE, 2000). In 2002, the Hong Kong Federation of Youth Societies conducted a study on social capital and civic identity (HKFYS, 2002, p. 51). In the study, 61.7% respondents indicated that they had not fulfilled the rights and responsibilities of “supervising the government”. Of whom, 38.9% adult respondents indicated they were not aware of the means to fulfil their rights and responsibilities, and 33.9% youth respondents indicated they did not know how to supervise. In addition, the study showed strong support towards the values of civil society such as “freedom”, “the rule of law”, “anti-corruption”, “equality”, “democracy” and “justice”. Of these values, the adult respondents regarded “freedom”, “anti-corruption” and “rule of law” as the top values, and the youth respondents regarded “freedom”, “anti-corruption” and “justice” as the top values (2002, 12 p. 68). What is more, most of the respondents regarded “freedom”, “rule of “, “hard work”, “anti-corruption”, “equality”, “democracy” and “justice” are shared values in Hong Kong. In this respect, there is a clear aspiration towards democratisation in the society, except that there is also a clear feeling of powerlessness in the politics. The traditional cultural has served as a tranquilizer towards the expression of these demands, but when the situation comes, these demands will be expressed explicitly. The Individuals In my study on Asian citizenship concepts, I manage to identify three features that can be quite distinctively Asian, which can also be applied to Hong Kong, namely, emphasis on harmony, spirituality and the development of individuality and the self (Lee, 2004b). These three features are interrelated. The significance of being able to identify and substantiate the three features I have identified earlier is important in a way that the three features are interrelated to form a philosophical stance – a fundamental concern in relationship which begins with the relation with the self and the relation with the universe, then extended to one another in the society. This fundamental starting point contributes to the orientation of citizenship in Asia towards the development of individuality that is characterized by the emphasis on spirituality. By spirituality, it is often referred to the enrichment of the one’s inner being, which is expressed in terms of self-cultivation and self-awareness. This helps to explain the emphasis on the citizen’s moral being rather than politics. This also helps to explain the depoliticized orientation of citizenship education in Asia. Although the citizenship education agenda can be rather politicized in terms of serving the state (as expressed in patriotism), the focus often reverts to the quality of the self, which is sometimes expressed in terms of the moral quality of the self. The emphasis underlies fundamental departure in agenda and approach to citizenship. As the 1996 Hong Kong Guidelines on Civic Education in Schools (Education Department, 1996) points out, countries emphasizing individualism are also concerned about collectivism, and vice versa. However, it is the point of departure that marks the fundamental difference. At least, it is really common in Asia that citizenship education is always in terms of civic and moral education rather than just civics. The latest Hong Kong curriculum reform document, Basic Education Curriculum Guide (2002c), even deliberately choose to name it “moral and civic education” – the concern for morality is the point of departure according to the Hong Kong document. References Au, Y.Y. (1994). Value Orientations in Junior Secondary (S1-S3) Chinese Language Curriculum of Hong Kong. Unpublished M.Ed. dissertation, University of Hong Kong. Choi, P.K. (1995) “Civic Education and National Education [Gongmin Jiaoyu yu Guomin Jiaoyu]”, Daily Express, 23 July. Committee on the Promotion of Civic Education (CPCE) (2000) Biennial Opinion Survey on Civic Education 2000. Hong Kong: The Committee. Curriculum Development Council (CDC) (2001) Learning to Learn: Lifelong Learning and Whole-person Development. Hong Kong: Curriculum Development Council. 13 Curriculum Development Council (CDC) (2002a) Four Key Tasks – Achieving Learning to Learn: 3A. Moral and Civic Education. Hong Kong: Curriculum Development Council. Curriculum Development Council (CDC) (2002b) Personal, Social and Humanities Education KLA Curriculum Guide. Hong Kong: Curriculum Development Council. de Bary, W.T. (1983). The Liberal Tradition of China. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press. Education and Manpower Bureau (EMB) (2004b) “Hong Kong Student Leaders Award Scheme: The Affection Towards China and the Heart for China”, http://cd.emb.gov.hk/mce/ni_course/intro.htm. (In Chinese) Curriculum Development Council (CDC) (2002c) Basic Education Curriculum Guide. Hong Kong: Curriculum Development Council. Education Commission (2000) Learning for Life, Learning through Life: Reform Proposals for the Education System in Hong Kong. Education Blueprint for the 21st Century. Hong Kong: Education Commission. Education Department, Hong Kong (1996) Guidelines on Civic Education, Hong Kong, Government Printer. Hong Kong Federation of Youth Groups (HKFYG) (2002) A Study of on Social Capital with Regard to Citizenship. Hong Kong: Youth Research Centre, Hong Kong Federation of Youth Group. (In Chinese) Law, Wing-wah (2004) “Globalisation and Citizenship Education in Hong Kong”, Comparative Education Review, Vol. 48, No. 3, pp. 253-273. Lee, W.O. (1996) ““From depoliticisation to politicisation: The reform of civic education in Hong Kong in political transition”. In Chinese Comparative Education Society – Taipei et al. (eds.), Educational Reform – From Tradition to Modernity (Taipei: Shi Ta Publishers Co., 1996), pp. 295-328. Lee, W.O. (2001) “Hong Kong: Enhancing the quality of the self in citizenship”. In Cummings, K William; Tatto, M. & Hawkins, J. (eds.), Values Education for Dynamic Societies. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong, pp. 207-226. Lee, W.O. (2004a) “Emerging concepts of citizenship in the Asian context”. In W.O. Lee, D.L. Grossman, K.J. Kennedy & G.P. Fairbrother (eds.), Citizenship Education in Asia and the Pacific: Concepts and Issues. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong/Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 25-35. Lee, W.O. (2004b) “Concepts and Issues of Asian Citizenship: Spirituality, Harmony and Individuality”. In W.O. Lee, D.L. Grossman, K.J. Kennedy & G.P. Fairbrother (eds.), Citizenship Education in Asia and the Pacific: Concepts and Issues. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong/Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 277-288. Lee, W.O. and Gu, R. (2004) Research on Global Citizenship Education in Hong Kong and Shanghai Secondary Schools. Hong Kong: Oxfam. (In Chinese) Lee, W.O. & Sweeting, A. (2001) “Controversies in Hong Kong’s Political Transition: 14 Nationalism versus Liberalism”. In M. Bray & W.O. Lee (eds.), Education and Political Transition: Themes and Experiences in East Asia. Hong Kong: Comparative Education Research Centre, University of Hong Kong, pp. 101-121. Lui, T.L. and Chiu, S.W.K. (2000) “Introduction – Changing Political Opportunities and the Shaping of Collective Action: Social Movements in Hong Kong.” In S.W.K. Chiu and T.L. Lui (eds.), The Dynamics of Social Movement in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 1-20. Man, S.W. (1996) “Beware of the Grand Statements of ‘National Education’ [Shenfang ‘Minzu Jiaoyu’ de Jiadakong]”, Sing Tao Daily, 28 August. 15