SCIENTISTS MARVEL AT DISCOVERY OF A NEW GIANT ORGANISM

advertisement

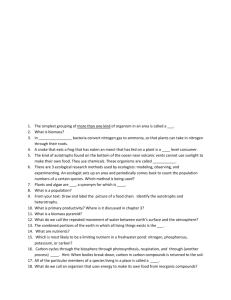

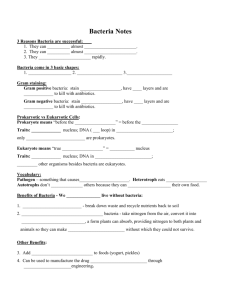

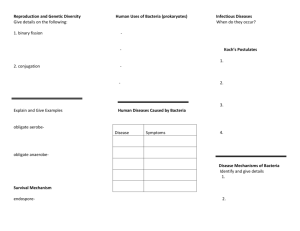

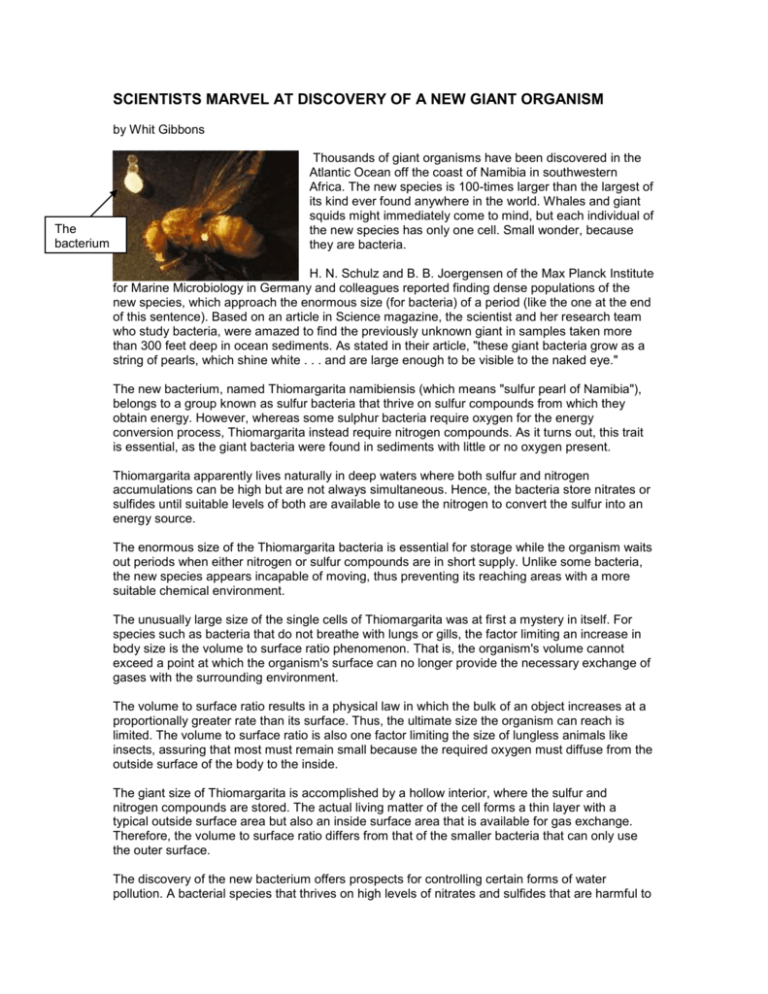

SCIENTISTS MARVEL AT DISCOVERY OF A NEW GIANT ORGANISM by Whit Gibbons The bacterium Thousands of giant organisms have been discovered in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Namibia in southwestern Africa. The new species is 100-times larger than the largest of its kind ever found anywhere in the world. Whales and giant squids might immediately come to mind, but each individual of the new species has only one cell. Small wonder, because they are bacteria. H. N. Schulz and B. B. Joergensen of the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Germany and colleagues reported finding dense populations of the new species, which approach the enormous size (for bacteria) of a period (like the one at the end of this sentence). Based on an article in Science magazine, the scientist and her research team who study bacteria, were amazed to find the previously unknown giant in samples taken more than 300 feet deep in ocean sediments. As stated in their article, "these giant bacteria grow as a string of pearls, which shine white . . . and are large enough to be visible to the naked eye." The new bacterium, named Thiomargarita namibiensis (which means "sulfur pearl of Namibia"), belongs to a group known as sulfur bacteria that thrive on sulfur compounds from which they obtain energy. However, whereas some sulphur bacteria require oxygen for the energy conversion process, Thiomargarita instead require nitrogen compounds. As it turns out, this trait is essential, as the giant bacteria were found in sediments with little or no oxygen present. Thiomargarita apparently lives naturally in deep waters where both sulfur and nitrogen accumulations can be high but are not always simultaneous. Hence, the bacteria store nitrates or sulfides until suitable levels of both are available to use the nitrogen to convert the sulfur into an energy source. The enormous size of the Thiomargarita bacteria is essential for storage while the organism waits out periods when either nitrogen or sulfur compounds are in short supply. Unlike some bacteria, the new species appears incapable of moving, thus preventing its reaching areas with a more suitable chemical environment. The unusually large size of the single cells of Thiomargarita was at first a mystery in itself. For species such as bacteria that do not breathe with lungs or gills, the factor limiting an increase in body size is the volume to surface ratio phenomenon. That is, the organism's volume cannot exceed a point at which the organism's surface can no longer provide the necessary exchange of gases with the surrounding environment. The volume to surface ratio results in a physical law in which the bulk of an object increases at a proportionally greater rate than its surface. Thus, the ultimate size the organism can reach is limited. The volume to surface ratio is also one factor limiting the size of lungless animals like insects, assuring that most must remain small because the required oxygen must diffuse from the outside surface of the body to the inside. The giant size of Thiomargarita is accomplished by a hollow interior, where the sulfur and nitrogen compounds are stored. The actual living matter of the cell forms a thin layer with a typical outside surface area but also an inside surface area that is available for gas exchange. Therefore, the volume to surface ratio differs from that of the smaller bacteria that can only use the outer surface. The discovery of the new bacterium offers prospects for controlling certain forms of water pollution. A bacterial species that thrives on high levels of nitrates and sulfides that are harmful to most animal species could be very useful. The bacteria convert the harmful compounds into harmless sulfur and nitrogen, thus cleansing the habitat. Such systems of biological control are seldom understood and developed overnight, but research directed at such a problem could result in major strides in environmental cleanup technology. Although the environmental prospects are encouraging, of even greater fascination is the fact that such a phenomenal organism could have gone to the last decade of the millennium without ever having been discovered. What else is out there that we still know nothing about? Environmental Commentaries, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, University of Georgia http://www.uga.edu/srel/