Having a pure quantitative approach is very limitating our

advertisement

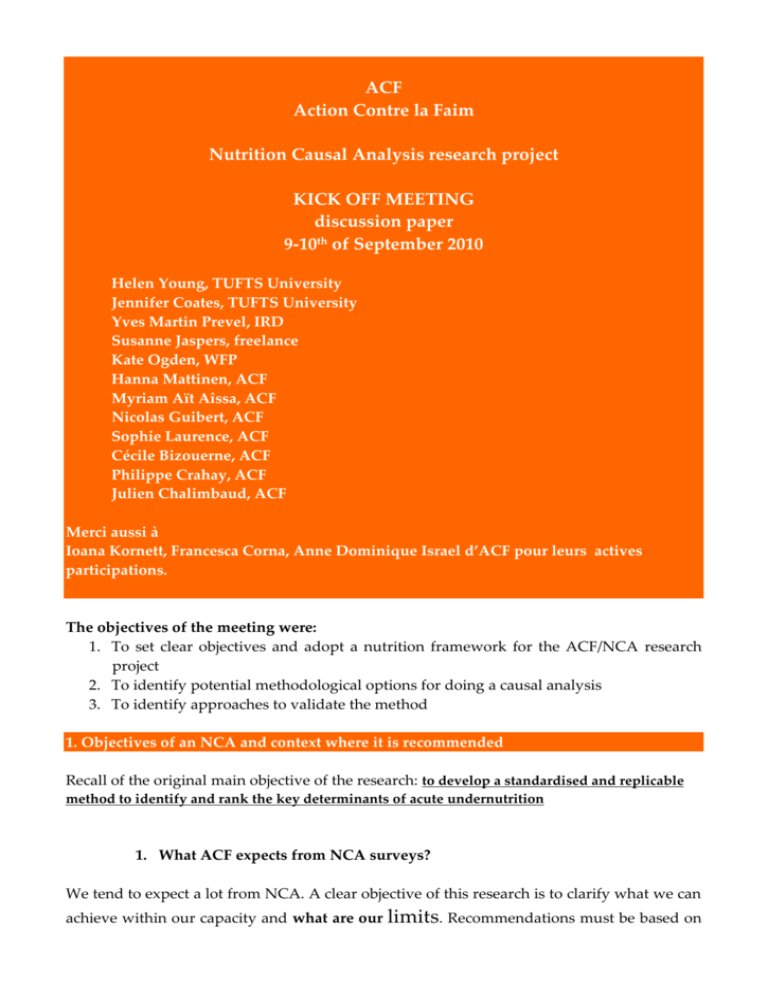

ACF Action Contre la Faim Nutrition Causal Analysis research project KICK OFF MEETING discussion paper 9-10th of September 2010 Helen Young, TUFTS University Jennifer Coates, TUFTS University Yves Martin Prevel, IRD Susanne Jaspers, freelance Kate Ogden, WFP Hanna Mattinen, ACF Myriam Aït Aîssa, ACF Nicolas Guibert, ACF Sophie Laurence, ACF Cécile Bizouerne, ACF Philippe Crahay, ACF Julien Chalimbaud, ACF Merci aussi à Ioana Kornett, Francesca Corna, Anne Dominique Israel d’ACF pour leurs actives participations. The objectives of the meeting were: 1. To set clear objectives and adopt a nutrition framework for the ACF/NCA research project 2. To identify potential methodological options for doing a causal analysis 3. To identify approaches to validate the method 1. Objectives of an NCA and context where it is recommended Recall of the original main objective of the research: to develop a standardised and replicable method to identify and rank the key determinants of acute undernutrition 1. What ACF expects from NCA surveys? We tend to expect a lot from NCA. A clear objective of this research is to clarify what we can achieve within our capacity and what are our limits. Recommendations must be based on solid arguments and therefore solid methodology. ACF implements NCA as a complex assessment of 2-3 months in a specific local context (typically at a district level). The first use of NCA by ACF is to define a intervention and programmes medium term strategy (2-3 years) of in order to reduce undernutrition (ACF is focusing on acute undernutrition). An NCA is a key tool for mainstreaming nutrition in all programmes and making sure that at least, for example, a food security programme does not increase risks of undernutrition. NCA can be also a powerful tool for advocacy. 2. Focusing on acute undernutrition and/or Stunting? This can vary according to the local objectives of a NCA and the context should we consider an NCA? context. In which ACF is keen to consider an NCA in contexts where undernutrition is not well understood and remains consistently at high levels. However, these context precisions do not really tell us on which type of undernutrition all NCA should focus on. When looking at medium term strategy, it seems relevant to focus on stunting 1. On the other side, there are multiple examples where acute undernutrition remains at high levels during a prolonged So an NCA can be relevant focusing on stunting or focusing on acute. However, stunting and acute undernutrition have different causes. Risk factors and pathways are different. period and is not well understood. Z.A. Bhutta and al2 have depicted the different pathways leading to stunting/acute undernutrition although it does not explore relations between stunting and acute per se: L.Smith; Marie T.Ruel; Aida Ndiaye “Why is child malnutrition lower in urban than in rural areas? Evidence from 36 developing countries”. 2004.IFPRI discussion paper. http://www.ifpri.org/publication/why-child-malnutrition-lowerurban-rural-areas-0 2 Z.A.Bhutta and al. “What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival”. The Lancet, 2008. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736%2807%2961693-6/abstract 1 During the meeting we reached the consensus that we cannot only look at acute linkages between stunting and acute? The linkages will differ from one context to another3. Does it imply a different methodology? An important aspect for methodological considerations is that timeframes are different. undernutrition without considering stunting. What are the It would be interesting to test the methodology in a country focusing on chronic and another one focusing on acute. An opportunity worth to be explored is the recent work by S.Nandy and J.Miranda on composite indicators (CIAF) of nutritional status4. 2. Undernutrition framework As portrayed in annexe 1, quite a few adaptations from the original UNICEF framework of 1990 have appeared since. Main frameworks used though are the original UNICEF framework; the Black Re and al5 adaptation published in the Lancet; the WFP one of 20096 and the ACF one recently published in SCN7. All are showed in annexe 1. C.G.Victoria. “The association between wasting and stunting: an international perspective”. The Journal of Nutrition 1991. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/abstract/122/5/1105 4 See Shailen Nandy and J. Jaime Miranda; overlooking undernutrition? http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2685640/ 3 5 Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C and Rivera J (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet 371: 243-60. Available at: www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(07)61690-0/abstract 6 WFP (2009) Emergency Food Security Assessment handbook. WFP:Rome. Available at: the main architecture of the framework has survived even after 20 years. There was a consensus to keep the framework as a concept, to keep it simple, generic and neutral so that it can be adapted to various situations. Beside adaptations, Rather than detailing a framework it seems more relevant to further develop a methodology to better use it. Nevertheless, strengths and weaknesses of the different frameworks need to be emphasized to develop a proper NCA methodology: 1. Crucial to have basic factors more prominent. From the original framework, two aspects are less emphasized in the more recent frameworks: people’s perspective and goals and the basic causes. - Either we visually represent all the impact of the basic causes on every risk factors. Then conceptual linkages need to be made between basic causes and undernutrition. - Or, as L.Smith and L.Haddad8 do recommend, we should have a separate analysis for each level: underlying causes are already integrating basic causes. From all the NCA gathered, often too little is mentioned about basic causes. 2. Nutrition Cycles and feed back loops Undernutrition is not only an outcome but also an input: 2 cycles are important : the nutrition life cycle (intergeneration links as low birth wait is a clear risk factor and is mostly determined by pregnant women’s nutrition status) and infectious cycle (loop between nutrition / health and food intake). They are not pictured in the main frameworks mentioned above. It is an important aspect when showing a link between poor health and undernutrition especially when looking at acute, doesn’t tell if health is a cause or a consequence of undernutrition. Careful methodology and conclusion are necessary. 3. Links with the livelihood framework www.wfp.org/content/emergency-food-security-assessment-handbook 7 ACF (2010) The threats of climate change on undernutrition: A neglected issue that requires further analysis and urgent actions, in: SCN, 2010. Newsletter #38 – Climate Change: Food and Nutrition Security Implications. Available at: http://www.unscn.org/files/Publications/SCN_News/SCN_NEWS_38_03_06_10.pdf L.Smith and L.Haddad. « Explaining child malnutrition in developing countries”, IFPRI 2002. http://www.ifpri.org/publication/explaining-child-malnutrition-developing-countries-0 8 ACF and WFP frameworks are putting the livelihood concept in a central position within the nutritional framework. The livelihood concept and framework attached is powerful for 2 reasons. It emphasizes the strategies and choices made at household level, based on available assets. Also, it is a well known concept, has a better political capital and is widely used by many field workers. On a weaker side, when we are talking about basic causes, we are not talking about livelihood assets. It is a wider perspective. Livelihoods concept does not integrate well public health and child care practices for example. Livelihood concept is well depicting the process of: availability / strategic choices of households / outcomes produced impacting available resources. However, a typical choice of, for example, “should I buy veterinary medicine for my only milking cow or bring my child to the health centre”, is not well pictured in the livelihood assessments and is critical for an NCA approach. It is pictured in the livelihood framework (human capital is there) but not in the livelihoods zone or livelihood groups of the Household Economy Approach. No consensus has been reached on this point. - Either we use ACF/WFP frameworks and enlarge/precise the definition of livelihoods in order to better integrate health / care practices access and use. - Either we use the Black Re or UNICEF frameworks. See proposed framework in annexe 1 which keeps the livelihood process but is not using the “livelihoods” term. 4. Dynamic aspect Dynamic aspects are not pictured in the original UNICEF framework nor in the Black Re one. WFP and ACF frameworks are strongly showing how risk factors are time bounded. 5. Scale of the framework A remark regarding the framework: virtually, one framework can be pictured for every child. A baby boy or girl from the same mother will not necessarily have the same care practices. The different levels of analysis are clear in the framework (individual / household / community) but we are however still often trying to draw a single framework for a vast diversity of situations. Review of the framework, remaining questions… Annex 1e and 1f are proposing 2 new frameworks depending on how we represent basic causes. Which one would be the most adapted? Further modifications to add/remove? Do we mention “housheholds assets” or “livelihoods assets”? Are the basic causes, and links for other components well pictured or need to be further detailed? 3. NCA validation protocol 1. Having a pure quantitative approach is restrictive as most multi-variate analysis have only been able to explain 15 to 25% of variability. Quantitative assessments have been trying to explain and rank different causes of undernutrition by testing key indicators one by one with undernutrition levels (weather chronic or acute). Indicators appearing to be significantly linked with undernutrition were then gathered in a multi variate analysis in order to explain undernutrition variability (for ex: 3% percent of undernutrition is explained by poor diet diversity score; 5% by education…). most of these multi variate analysis explain only a small part of variability of undernutrition. This is leading to few thoughts: Are quantitative analyses inadequate or can multi-variate analysis be improved? Does it mean that designing interventions targeted towards main determinants will have a limited impact? 2. Can quantitative / multi-variate analysis be improved? These studies are often based on large samples from national databases and are limited by the number of indicators available. The choice and interpretation of indicators or proxy indicators is very tricky and often limited. There is no point identifying a key determinant that is being driven by something else. This helps drive silos problems. Another limiting factor is the variability in the sample: comparing different countries dataset shows more variability in the sample than national surveys / local surveys. For example the cross country survey by L.Smith and L.Haddad9 have shown much better results and are confident to explain through only 4 proxy indicators most of the variability of undernutrition. A limit of this study is the careful interpretation of the 4 proxy indicators used. Another factor of success of this survey is to have 2 multivariate models: one for basic causes and another for underlying causes: “A bias results in the fact that impact of basic causes is already picked up by the variable it determines (underlying causes)”. 9 L.Smith and L.Haddad « explaining child malnutrition in developing countries ». 2002. http://www.ifpri.org/publication/explaining-child-malnutrition-developing-countries-0 Path analysis methodology could be an appropriate technique to consider as it explores better the interdependencies of causal factors10. Including new indicators with geographical variables (GIS) can potentially increase our understanding. The Case-Control methodology seems more powerful as it reduces sample size which is a major constraint. This methodology was used in Colombia11 in 2007 to explain 77% of the mortality cases due to wasting with only 6 risk factors. 3. If only a small proportion of the prevalence of undernutrition is explained by determinants, does it mean that designing interventions targeted towards those main determinants will have a limited impact? positive and important impact has been demonstrated of an integrated approach to reduce undernutrition acting apparently only on few risk factors. Looking back at the Iringa experience12 and also the Laos GTZ integrated project, For example, the successful experience of GTZ in Laos, S.Kaufmann showed that 3 interventions where having a direct impact on undernutrition: improve agricultural system; improve water system and water treatment. Households not having any of the 3 interventions were having chronic undernutrition rates of 73% whereas those having endorsed all of the 3 interventions were having chronic undernutrition rates of only 25%. It does not mean that those 3 interventions reduced automatically undernutrition by -50%. As strongly mentioned in the Iringa experience (and the triple A strategy), a community approach is the basis for increasing impact of interventions. Bringing political actors, community leaders, head of households, mothers around main determinants of undernutrition, with appropriate information and means for action, is a key success factor. The how is at least as important as the what. An interesting perspective is to see how this successful bottom up approach melds with the current international trend towards large scale specific interventions 13. Maybe a starting point would be to ask whether there is any information to indicate that this essential package, and the problems it aims to resolve, is not likely to appropriate in x context for y reason. Once barriers are removed, or the package is tailored, then perhaps it is more likely to succeed. So, we would be starting with well-defined hypothesis and essentially testing to see if we could disprove them, and if yes, then provide some understanding for why they don’t hold in a certain context. 10 See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Path_analysis_%28statistics%29 Gobernacion de Antioquia « mortalidad por desnutricion en menores de cinco anos en el departamento de Antioquia”. 2007. 12 UNICEF. “Improving Nutrition in Tanzania in the 80s: the Iringa experience” 1992. http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/eps25.pdf 13 Essential Nutrition Action initiative, linkages project. See also ref 11. 11 4. Using a quantitative NCA is not the only way to identify and rank main determinants of undernutrition. Ranking/discriminating determinants implies to have criteria for ordering them. When using a quantitative / multi variate analysis, it implies that the criteria used for ranking is the statistic explanation of the undernutrition variability. This criteria is debatable. First for its reliability: an analysis relies only on existing indicators in the survey. More important indicators might be missing and not pictured in the analysis. Also when looking at a homogenous population, some key factors might affect the whole population. A statistical analysis will not be able to reveal this factor as there is no diversity in the sample. If the aim of ranking is meant for targeting intervention, then targeting the “statistically most important determinants” might not be the best way to ensure the highest impact. Furhtermore, the dynamic aspect is critical: main risk factors are evolving through the seasons and main determinants should not be identified only looking at a specific time in the year. 5. Dynamic aspects of an NCA Causes of undernutrition are changing with time. The timing of the NCA assessment is an important aspect in the interpretation of the results. In order to provide a dynamic aspect to NCA, two approaches are possible: split the NCA in a baseline + continuous “monitoring” tools or extrapolate dynamic aspects of the main risk factors identified (one by one). 6. Scale of the framework: “nutrition vulnerability groups” We focus on trying to identify causes, but adopting a more descriptive approach of the group and the main causes can help identify nutrition vulnerability groups. Livelihood groups are not fully satisfactory as they are not uniformed with care practices, nor with access and use of health care (although it is included in the livelihood framework).One solution is to look through the hypothesis identified in the initial phase: if they don’t suggest that causes of undernutrition are different across livelihood/ethnic/urban group then we don’t need to disaggregate. 7. Linking an NCA with an anthropomethric survey In order to have a good first understanding of nutrition patterns (prevalence, heterogeneity…) in an area, a nutrition survey should be done before an NCA, except if secondary data is sufficiently detailed. It is not possible to do an NCA with a nutrition survey (time, sample, methodology and objectives are different). 8. Sequences for an NCA : Qualitative – Quantitative – Qualitative: It is clear that a dual qualitative (making hypothesis) and a quantitative approach (testing the hypothesis) would be relevant for an NCA. As it is an iterative process, a final phase of qualitative to further interpret the information gathered and refine initial hypothesis should be valuable. NCA validation protocol Linking NCA and nutrition surveys: what type of nutrition survey (rapid or SMART)? What information is exactly expected from nutrition survey? See example of Sierra Leone with WFP. What nutrition indicators in the NCA we would be looking at? Pathways and case control methodologies to be further explored. How to better underline dynamic aspects of undernutrition in the methodology? Based on the proposed sequence of the NCA assessment, what parts of the method need to be standardized and others to be contextualized? Annexe 1 a: UNICEF Framework 1990 http://www.ceecis.org/iodine/01_global/01_pl/01_01_other_1992_unicef.pdf Interestingly, the framework included in the above link is not exactly the same as the one below which was published by UNICEF. In the published one (below) “formal and non formal institutions” have replaced the “resources and control” box. Annexe 1b: Black re and Al framework 2008 Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Mathers C and Rivera J (2008) Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. The Lancet 371: 243-60. Available at: www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(07)61690-0/abstract Annexe 1c: WFP Framework 2009 WFP (2009) Emergency Food Security Assessment handbook. WFP:Rome. Available at: www.wfp.org/content/emergency-food-security-assessment-handbook Annexe 1d: ACF Framework 2009 ACF (2010) The threats of climate change on undernutrition: A neglected issue that requires further analysis and urgent actions, in: SCN, 2010. Newsletter #38 – Climate Change: Food and Nutrition Security Implications. Available at: http://www.unscn.org/files/Publications/SCN_News/SCN_NEWS_38_03_06_10.pdf Annexe 1e: proposed framework v1 Short Term Consequences: Mortality, Morbidity, Disability Long Term Consequences: Adult size, intelectual ability, economic productivity, reproductive performance, metabolic and cardiovascular disease Nutrition Status Immediate Causes Dietary Intake Underlying Causes Basic Causes Shocks, trends, seasonality Food Security Health Status Maternal, infant and young child care practices Access to quality water, sanitation and health services Households strategies, traditions and beliefs Households assets Natural, physical, human, social, financial and political Policies, formal and informal institutions Context, Potential resources, services and infrastructures Annexe 1f: proposed framework v2 Short Term Consequences: Mortality, Morbidity, Disability Long Term Consequences: Adult size, intelectual ability, economic productivity, reproductive performance, metabolic and cardiovascular disease Nutrition Status Shocks, trends, seasonality Underlying Causes Dietary Intake Food Security Health Status Maternal, infant and young child care practices Livelihoods strategies, traditions and beliefs Livelihoods assets Natural, physical, human, social, financial and political Access to quality water, sanitation and health services Context: Potential resources, services and infrastructures Immediate Causes