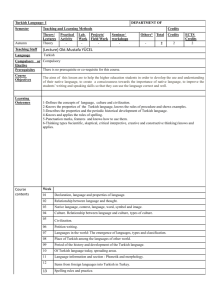

Dichotomies in education (1980-present)

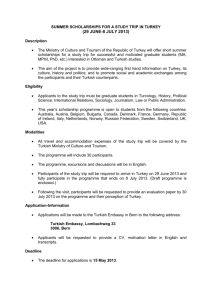

advertisement