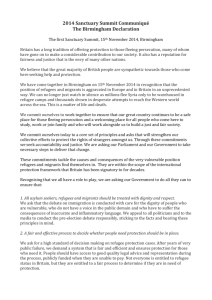

Between Voluntary Repatriation and Constructive Expulsion

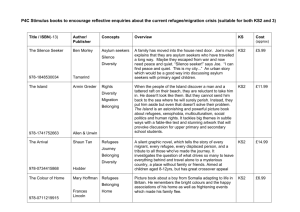

advertisement