Shell is a company that praises itself as ethical

advertisement

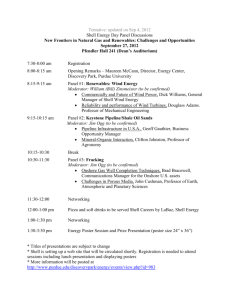

Shell´s Environmental Responsibility in Vila Carioca, Sao Paulo, Brazil 1 by Jose Antonio Puppim de Oliveira Associate Professor Brazilian School of Public and Business Administration - EBAPE Getulio Vargas Foundation - FGV Praia de Botafogo 190, room 507 CEP: 22250-900, Rio de Janeiro - RJ, Brazil phone: (55-21) 2559-5737 fax: (55-21) 2559-5710 e-mail: puppim@fgv.br Introduction: Shell defines its aim as “to meet the energy needs of society, in ways that are economically, socially and environmentally viable, now and in the future.”2 Shell was one of the pioneers in the movement for Corporate Social Responsibility. The company says it is committed to sustainable development and human rights: “Our core values of honesty, integrity and respect for people define how we work. These values have been embodied for more than 25 years in our Business Principles, which since 1997 have included a commitment to support human rights and to contribute to sustainable development.”3 The case in Vila Carioca (São Paulo City) below illustrates a tough decision the company must make in order to keep its commitments, especially when the company’s past actions occurred in a different institutional and regulatory environment. Vila Carioca is a neighborhood in the southern part of São Paulo, the largest city in South America.4 Greenpeace and the Union of Workers in the Mining and Petroleum Sector (Sinpetrol) alleged in the 1990s that the region had its soil, air and water contaminated by several pollutants from industrial activities that took place in the area. The pollution may have contaminated approximately 30,000 people residing in the area.5 Shell is accused of being one of the main sources responsible for the pollution among companies operating in the region. One national newspaper (Folha de São Paulo) considers that Vila Carioca may be the most contaminated area in São Paulo, if this accusation is true.6 Shell has been in the area since 1951 and has disposed large amounts of residues in the soil for decades, which may ultimately be the source of soil, air and underground water contamination. The liability can reach significant values, as some specialists conclude that part of the land should be expropriated for cleanup and those populating the area should be relocated and compensated. However, the company claims that it followed all existing environmental laws and used the best technologies available. Actually, most of the material was disposed of long before the new environmental laws were passed. The regulations applicable at the time were followed, and Shell used worldwide 1 This case was based on newspaper articles, web sites, reports and conversation with people involved in the case from different parts, including Shell. 2 From Shell´s web-site: www.shell.com, (Who We Are) accessed on March 18th, 2005. 3 From Shell´s web-site: www.shell.com, (Who We Are) accessed on March 18th, 2005. 4 The municipality of São Paulo had a population of 10.4 million in 2000. Its area is 1,523 square kilometers. The 39 municipalities of its metropolitan area had approximately 17 million inhabitants in 2000 (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics-IBGE, Census 2000 published in 2003). 5 This is the estimate of the public attorneys (Folha de São Paulo newspaper, 04/20/2002) 6 Folha de São Paulo, 15/06/2002. 1 standards and the best available technology. Sometimes the company even did more than the law asked. There were also other industrial companies with environmental problems in the region that may have contributed to the problem. Shell argues that many perceptions of people involved are based on rumors and non-scientific facts. The company says that it worked with scientific information and the problem is not as terrible as the media portrays. Therefore, to what extent is Shell responsible for solving the problem? Should the company be liable for the problem? Can the behavior of Shell in the case be considered ethical and acting according to its principles of social and environmental responsibility? Vila Carioca Vila Carioca is a typical working class neighborhood that could be found around many industrialized areas in developing countries (DC). The region grew as a mix of industrial and residential areas with little planning for separating the population from risk activities, such as oil tanks and pipelines (see Figure 1 at the end of the case). Initially, in the 1950s, Vila Carioca was only an industrial zone, but as the city of São Paulo grew at a fast (and unplanned) pace, people started to move in and establish their residences around the industrial plants. After the 1970s, many plants closed down or moved due to the de-industrialization of parts of the city of São Paulo. This significantly increased the proportion of residential settlement in São Paulo. The settlements were both formal (titled and licensed) and informal (slums or favelas, and unlicensed housing built on untitled land). The environmental history of Shell in Vila Carioca started in 1951, when the company built a storage tank and a terminal in the area. These facilities were upgraded several times and the plant was still operating in 2004. Shell also had a plant which produced pesticides. However, this plant moved out of Vila Carioca in the 1970s. Shell’s facilities have always had the best available technology and had followed the current environmental regulations as well as world standards. The Discovery In March of 2003, the city government announced that an area of 180,000 square meters (approximately 25 soccer fields) around the Shell plant in Vila Carioca was contaminated with various toxic pollutants, including heavy metals7 and “drins.”8 The city attorney sued Shell and 7 Heavy metals mean any metallic chemical element with a moderately high density. Many are toxic or poisonous at even low concentrations. Examples of heavy metals include mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), chromium (Cr), and lead (Pb). The impacts of heavy metals on human beings are relatively well known. Exposure to some of the heavy metals can result in a wide range of health effects depending on the level and duration of exposure, such as the malformation of fetus; problems in the synthesis of hemoglobin; effects on the kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, joints and reproductive system; and acute or chronic damage to the nervous system (for more details see www.lenntech.com/heavy-metals.htm). 8 “Drins” is the general term used for a group of organochlorides, such as Endrin, Dieldrin and Aldrin, used as pesticides in agriculture. The United Nations Organization (UN) convention on POPs (Persistent Organic Pollutants), or the Stockholm Convention, recommended banning the production and use of drins: “POPs are chemicals that remain intact in the environment for long periods, become widely distributed geographically, accumulate in the fatty tissue of living organisms and are toxic to humans and wildlife. POPs circulate globally and can cause damage wherever they travel.” (from the Stockholm Convention website http://www.pops.int/, accessed on May 18th, 2005. 2 the State Environmental Agency (CETESB), which were respectively accused as a source of the pollution and negligence in enforcing the environmental laws. However, the case was criticized much earlier than the 2003 lawsuit. In 1993, Greenpeace and the Union of Workers in the Mining and Petroleum Sector (Sinpetrol) filed a joint court complaint against Shell. The case was left to the State Environmental Agency (CETESB), who took only minor measures before the city officially entered in the case. For decades, industrial plants in the region discharged toxic pollutants in the soil and air, and in doing so they had also contaminated the underground water. Initially, six wells in the region were closed. Although there was only one officially registered well in the region, there were others that were “unofficial” or clandestine. In one of the wells, whose water was used for human consumption, the level of dieldrin (one of the “Drins”) in the water was 0.327 micrograms per liter, more than one hundred times the permitted limit of 0.03 micrograms per liter. A report from the public attorney (Ministerio Publico) estimated that the pollution could affect the population. The city public attorney for accusation (Promotor Publico) estimated that as many as 30,000 people in the neighborhood could have been affected.9 Those dwelling in the area were in despair when they found out about the pollution problems that they barely understood. Many of them were not informed officially about the problem, as a woman said: “I was born here and I only knew about the case through the newspapers. I had always planted vegetables in the yard, and I thought my family was eating healthy food....”10 Others even said they suspected that something was wrong with the water. “The water is yellowish, smelly and the drops even stain the clothes...” another woman mentioned. Until 2002, almost ten years after the first charges in 1993, many people still felt abandoned by the public authorities and Shell, as they fought in court. Meanwhile, nothing was done and almost no one was properly informed about the situation. The population underwent a few voluntary medical tests which were completed by two private clinics at the request of an investigation team from the city council.11 Other dwellers were afraid Vila Carioca would become a “ghost” neighborhood, as some residents were moving out. In the sea of misinformation, some feared the worst: outbreaks of terrible diseases, the contamination of their kids, a drop in the price of their real estate, or even that the residents of Vila Carioca would become stereotyped as contaminated people. Despite the circumstances, many local residents wanted Shell to stay. Shell provided jobs and income, and many residents and neighbors of Vila Carioca actually worked for Shell. Nonemployees were afraid if Shell moved, the neighboring slum (favela) of Heliopolis would expand to occupy Shell’s land and increase the overall size of the favela. Shell´s Position12 Shell was established in Brazil in 1913 and in Vila Carioca in 1951. The company works in the sectors of fuel distribution, production of lubricants and chemicals, and most recently 9 Folha de São Paulo newspaper, 04/20/2002. Folha de São Paulo newspaper, 05/04/2002, in the article ”Moradores da Vila Carioca usaram poço no auge da contaminação.” 11 Shell and the State Environmental Agency (CETESB) do not recognize the validity of the test because they disagree with the methodology. 12 All information included in this section is based on newspaper articles and interviews with personnel from Shell. 10 3 petroleum exploration. Its net income was R$ 7.65 billion in 2000.13 The company provides 2,130 direct jobs and approximately 60,000 indirect jobs (associated and contracted companies and service stations). It is the largest private distributor of fuel in the country, accounting for approximately 20% of the market. It has a network of 3,000 gas stations around the country.14 In Vila Carioca, Shell has a distribution terminal with the capacity of 50 million liters, and used to have a pesticide plant until the 1970s. There were 165 employees in the terminal in 2002, a number that is relatively low compared to the number of workers in the past when Shell produced pesticides.15 The city government claims that the soil and underground water in the region surrounding Shell’s property is contaminated with organic and lead compounds, which in the past were used as additives to the gasoline. Before the 1970s and prior to the magnitude of current environmental issues, those compounds were the result of Shell’s normal procedures to clean up gasoline tanks. The residues from the internal crust of the gasoline tanks were simply buried in the soil during several decades until the 1970s. In the past, these were the standard procedures in the petroleum sector around the world. The company had taken several actions to remedy this problem, such as conducting studies to make the company’s procedures more environmentally friendly and incinerating 2,500 tons of contaminated soil and fuel crust. However, representatives of Sinpetrol (labor union) said these actions were not enough. They claimed Shell had the responsibility of avoiding the dispersion of the pollutants to areas outside the company by walling off the affected areas with concrete. The public attorney thought the state environmental agency (CETESB) was too lenient with Shell in the case and said in April 2002, “Shell’s actions limited the material that was the source of the contamination and left the decay of the pollutants in the subterranean water to nature… Moreover, CETESB agreed with this situation.”16 The official from the state environmental agency (CETESB) argued “the awareness and techniques to deal with contaminated areas are recent, both to us and to the companies, so we expect things go faster now than they did ten years ago”17. Even though Shell implemented many actions to try to solve the problems, it kept silent in many cases to avoid being deemed the only responsible company in the case. When both Shell and the state environmental agency (CETESB) were sued, they preferred not to comment on the claim. Shell mentioned in a note to the public that the remediation of the problem had been carried out, and that “the company had rigid codes of conduct and values to assume its responsibility for the results of its operation.”18 Other companies were suspected of contributing to the contamination. For example, BR (a subsidiary of Petrobras, a state enterprise, which is the largest company in the country) kept a deposit of 250 old tanks and several trucks in a property next to Shell’s. Those tanks were thought to leak fuel into the soil. BR still operates its plant. One hundred or more industrial plants were located in the region, ranging from paints, refineries, fuels and other chemicals. Besides, the traffic is intense, and Shell itself received more than 200 vehicles per day. 13 R$ = Real, the Brazilian currency. U$ 1 is approximately R$ 3 (it varies significantly over the years) in 2004. From Observatório Social (2002). Company Map: Shell. CUT – Unique Central of Workers Syndicate (www.observatoriosocial.org.br). 15 These employees include Exxon´s employees. Exxon (Esso) and Shell share parts of the activities of the terminal since 2001 (Observatorio Social, 2002). 16 Folha de São Paulo newspaper, 04/20/2002. 17 Folha de São Paulo newspaper, 04/20/2002. 18 Folha de São Paulo newspaper 04/20/2002, in the article “Shell descarta risco à saúde; Cetesb não.” 14 4 In relation to the “drins”, Shell did not initially accept the charge. The company argued that the compounds came from other companies in the region, such as the bankrupt pesticide plant from the Matarazzo group. However, later on, representatives of Shell admitted that the concentration of certain drins in parts of the soil of the company was over the accepted standards. In the case of Aldrin, the concentrations reached 1,320 times the limits established by the state environmental agency (CETESB). The concentration of Isodrin peaked at 2,450 times the allowed concentration in the European Union where the company has its headquarters. Shell produced pesticides (the source of drins) from the 1940s until the 1970s, when the pesticide plant was transferred to Paulinea in the state of Sao Paulo.19 The company also argues that the organic lead found in the area was not from the company, because it transformed its organic lead into inorganic lead before burying it underground. From the beginning of Shell’s environmental problems in Vila Carioca, the company received several fines. It was fined once by the regional office of the city government (for operation without proper license) and four times by the state environmental agency (for water contamination and delay in reporting the conditions of its water and soil) between 1993 and 2003.20 However, until 2003, the company had yet to pay and had appealed all of these fines. The contamination of the water charge was also challenged by Shell. In the beginning, Shell only admitted to the contamination of its property even after Shell hired a firm who produced a technical report which mentioned the contamination of the neighborhood’s water in 2000. The water contamination was also found by the municipal sanitary agency at a later date. The city started to identify the people, who live around the company, to analyze the degree of exposure they had to the contamination of the water. The company has carried out several studies to find out about the contamination and its impacts on the environment and on the population, including risk analysis and remediation plans for the whole region. According to a Shell Environmental Health and Safety manager, the company’s Risk Assessment and Environmental Report of the region is the “largest and most complete environmental study in a specific area ever done in Brazil.”21 These studies were needed to satisfy demands from both the state and municipality; however, the state environmental agency (CETESB) concluded that the studies conducted for the municipality did not fit the state requirements. This disagreement between the two governmental units created more confusion. The company says that it is “acting in a clear, transparent and responsible manner regarding all stakeholders, such as public officials, media and population.”22 However, until 2002, Shell did not actively inform those stakeholders about the problem. The company also did not send representatives to a meeting organized by the community in Vila Carioca to discuss the problem and solutions. A health check carried out voluntarily by a private clinic found a high incidence of lead in the body in nine out of the twenty-eight individuals analyzed, with four people in an elevated stage of contamination. Neither Shell nor the state environmental agency (CETESB) recognized the test as valid, and claimed that the methodology was flawed.23 According to studies of risk assessment carried out by specialized firms, Shell alleged that health checks were the responsibility of public organizations, so the company did not intend to carry out these checks on the population living around the plant. The courts also denied the request of 19 Shell Paulinea is another case of contamination by drins. According to Folha de S.Paulo newspaper on 04/16/2003 in the article “Cetesb decide aplicar multa diária a Shell.” 21 From an interview made by the author. 22 According to a note sent by email to Folha de S.Paulo newspaper on 05/13/2002, in the article “Contaminação de solo e águas passa dos limites da Shell.” 23 According to Folha de S.Paulo newspaper on 06/13/2002 in the article “Exames apontam contaminação na Vila Carioca (SP).” 20 5 the public attorney to require Shell to do the health checks. Shell claims that the case is not as dramatic as the media has portrayed it to be, so there is no need for panic. The company also thinks that this situation is the responsibility of the public authorities. Shell employees say that the community and some public authorities do not understand their position, and are acting emotionally instead of scientifically. There are several other demands made for Shell since the initial contamination finding. The state environmental agency has asked the company to install flexible roofs to capture part of the vapors that were coming from the fuel tanks filling the trucks. The municipal sanitary agency wants Shell to help the neighborhood population, despite the mixed results of the investigations over the contamination. The last negotiations involved a legal agreement for action among Shell, the municipality, the state and public attorneys. This agreement, known as the Term of Adjustment of Conduct (TAC in Portuguese), would require Shell to take several legally binding actions to remedy the environmental problems and seek treatment for the affected population. Though the company was always open to negotiation, it was reticent regarding the health issues. Shell indicated it needed a clear assurance that the environmental issues resulted directly from their activities, and were not the consequences of the contamination from the many other companies in the region. Shell argues that “we are part of the society, so we want to solve the problem jointly.”24 The company is willing to assume some responsibility in the case as a socially responsible corporation, and promises to treat the case properly and scientifically by contributing to the needs and welfare of the community; however, Shell wants to make sure that similar cases will not happen again. The company wants to treat the case purely from the scientific point of view by using the best methods and techniques of risk assessment and risk management. They see no point in spending huge amounts of resources to clean up the area completely because the risk is overcome if no one drinks the subterranean water. Moreover, Shell claims other companies may also be responsible and the problem quite possibly may continue into the future. The cleanup will not improve the quality of life of Vila Carioca or São Paulo´s inhabitants since underground contamination and other environmental problems such as air and water pollution are common in the city. Shell argues that it prefers to use its resources to contribute to the society in a more sensible way with other social and environmental initiatives. Shell´s Environmental Responsibility The case of Vila Carioca is similar to many other cases of environmental contamination in Brazil and other parts of the world. The problem exists, but stakeholders are not aware of the degree of the problem, who caused it, to what extent, and who should be held responsible. Moreover, there are clear differences among stakeholder perceptions. The population and some public authorities perceive the case as dramatic and fear the results of the contamination. Shell, based on its studies and technical capacity, says that the problem is not severe and denies the need for worrying once there is a very low risk of human contamination. Shell is a company with strict public codes of conduct regarding social and environmental issues. In the case, the company followed all existing environmental guidelines since the beginning of the environmental regulation in Brazil in 1970s, and had even done more 24 From a interview conducted by the author with a EH&S manager of Shell involved in the case. 6 than the regulations asked in some cases. The contamination seemed to have occurred before regulations were established and from an old plant that closed down decades ago. Even though the company was defensive in some instances, it worked closely with the public authorities responsible for the case, and took several actions to remediate the problem. Moreover, Shell was one of the many companies operating in Vila Carioca. It was the main suspect for causing the problem, but not the only one. Other companies may be responsible as well, such as BR Distribuidora (Petrobras), a pesticide plant of Matarazzo Group, which does not even exist anymore (and it is suspected that it left messy environmental problems), as well as dozens of smaller companies. Therefore, several questions can be raised regarding the case. Questions about Shell: 1. To what extent is Shell responsible for the problem? 2. Have its actions been enough to cope with the problem? 3. Should the company assume liability and pay for the complete cleaning up and compensate the people who were contaminated? 4. Can the behavior of Shell in the case be considered ethical and acting according to its Business Principles? Questions about multinational companies and regulatory issues based on the case: a) Should multinational companies apply in the host country’s the same environmental standards they have in their home countries? Even if these standards make their activities much more expensive and less competitive? If the Shell case were in a developed country (USA or Europe for instance), would Shell’s behavior be different? b) Should multinational companies be expected to follow higher environmental standards than a local company in a developing country because they have more access to financial resources and technology? c) Should a company like Shell agree with the perception of the people in the community and act according to this, even if this perception is not based on scientific information? Or should it act only according to scientific information? d) Should the company that contaminates the environment expend a lot of money to clean it up even when there is no risk to the population? Or should it use its resources for other more urgent environmental and social demands? e) Should a company be liable for negate environmental and social impacts that happened in the past, even when it followed strictly all environmental regulations existing at the time? 7 Figure 1 – Photo of the Shell Plants and other facilities in Vila Carioca 8 About Figure 1 Source: Shell. Explanation: Shell Facilities in bright color (BIP I, BIP II and Colorado). Other industrial plants and relevant sites are marked with red letter. All other buildings are housing. Translations of the marked sites: - Air Liquid = company that produces industrial gases Antiga Matarazzo Refinaria/Fábrica de Pesticidas = Matarazzo Pesticide Plant that was closed down Antiga Lagoa de Decantação da Matarazzo = Matarazzo Effluent Lagoon Antigo Lixão = former site of a municipal uncontrolled garbage disposal Condominio = Housing development Detran = State Department of Vehicle Control Agency Distribuidora de Combustível = Fuel distributor Linha Ferrea = Railroad Lopsa = Metal working company Metalúrgica = Metal working company Recauchutadora de Pneus = tire recovering firm Ribeirão dos Meninos = River Riberão dos Meninos Sommer = company that produces flooring Transdupla = Chemical products transportation company Trikem = company that produces industrial gases 9