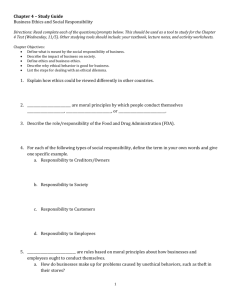

Chapter 5

Writing Ethically

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

The objectives of this chapter are to

Illustrate how workplace communications are often riddled with ethical implications.

Explain the philosophical perspectives of ethics.

Identify professional ethical obligations.

Explain the role of codes of conduct.

Identify unethical writing practices, and explain what makes them unacceptable.

Discuss the importance of anticipating the consequences of one’s actions.

Provide guidelines for managing unethical situations.

TEACHING STRATEGIES

This is a great chapter for getting students to think beyond the pedantic rules of writing that they often think dictate good communication (“Never end a sentence in a preposition,”

“Don’t use ‘I’ or ‘me,’” and “Always have three sentences per paragraph and three paragraphs per page”). Exploring the real rights and wrongs—and the inherent gray areas in between—of effective communication can help students gain a bit of confidence so that, with practice, they can use their skills to untangle and logically approach seemingly complex situations. This chapter is an equally good reminder that just following the rules of thumb for good writing is not enough. Professionals must think about what they say and how the audience will perceive it. Corner cutting or intentionally vague wording can have an unexpectedly big impact in our world of knee-jerk lawsuits and fierce competition.

Our daily new stories are full of wonderful, real-life examples of questionable communication ethics. Engage students by having them identify and explain such cases in the areas of advertising, research reporting, politics, etc. Help reinforce a healthy skepticism that will encourage students, both as readers and as writers, to evaluate the intentions of what they input and output.

You have several good opportunities in any semester to introduce this chapter. Early in the semester when you are discussing the nature and role of communication, a discussion of ethics can introduce students to the concept that, yes, ethics do matter in communication!

During the résumé and application letter assignment(s), students can easily relate communication ethics to puffing up their experience claims, choosing which action verbs to use, or deciding when to round a GPA up to the next decimal point. During a design and graphics-heavy assignment, students can apply communication ethics to the clarity and intentions of functional graphics or to the emphasis created through design techniques. This is also a great chapter to use near the end of the semester, even for a final exam. Students can

92

reflect on the communication skills they’ve learned by considering how ethics is directly related to the application of those skills.

WORKSHOP ACTIVITIES

Here are some ideas for workshop activities to help students learn about the communication ethics issues covered in Chapter 5.

Traditional Classroom

1.

Interview professionals concerning their communication ethics.

Whether you have a guest speaker or students (alone or in pairs) interview professionals, first brainstorm together what questions to ask. Help them remember to explore issues such as corporate ethics policies, unwritten codes of behavior, common practices that may still be ethically questionable, and situations where the interviewee had to make ethical decisions. If the students do the interviews outside of class, let them know that their interviewees can remain anonymous if they desire to do so.

2.

Consider how communication ethics apply to graphics. Have students bring some common newsstand magazines to class (or you bring a few). In pairs or small groups (no more than four), have them search through the magazines for examples of graphics that may be unclear in design or content. Have them discuss whether they think the poor graphic design is intentional or careless. Ask them how they would change the design to improve the graphics’ clarity while maintaining their attractiveness and attention-getting features.

3.

Debate both sides of an ethical dilemma.

Have student pairs or small groups brainstorm ethical dilemmas they face at school and/or at work. After gathering a good sample of these ethical contexts, let them vote on several to debate. After choosing sides, have them argue over possible areas of unethical communication practices and on solutions to any problems.

Computer Classroom

1.

Anonymously discuss previous communication ethics dilemmas.

Have students log on to a chat room that allows creative usernames and/or anonymous posts. If possible, limit students to groups of four (a number of Internet sites offer free chat room creation and access). Have them candidly discuss positive and negative communication ethics experiences. Spend a few minutes lurking in each chat room to keep them on task and to keep the discussion headed in a productive direction. Afterwards, have each student first summarize the problems and successes discussed. Then address the problems by offering solutions.

2.

Find and compare two or three online codes of ethics.

Divide students into small groups, and have them search the Web for online ethics codes. Once they have found the

93

assigned number (two, three, four, etc.), they should compare what issues are addressed and what recommendations are given. Applying these to the students’ current academic experiences and future (expected) professional lives may help make the concepts a bit more concrete.

WRITING PROJECTS

This chapter can serve as the central tenant of an assignment or as a support chapter for postwriting reflection. Throughout a semester, you can even use it in both capacities. Here are some ideas for a variety of projects related to Chapter 5.

Traditional Assignments

1.

Write a complaint letter using some of the unethical behaviors discussed in the reading.

Much like the backwards style assignments in Chapter 4, students will gain some insight into crafty manipulation by trying to use it themselves. Two possible extensions of this assignment include requiring an additional cover memo explaining the unethical approaches and having students trade complaint letters and read/react from the audience’s point of view.

2.

Write a cover memo to attach to a major project discussing the ethical dilemmas that the project generated.

After completing a major project such as a report or instructions manual, have students reflect on what unethical temptations they faced, how they solved these problems, and even how teachers might encourage ethical student behavior in the future. If a student finds that he or she has made a minor ethical mistake

(this does not mean major plagiarism!) during this review, then this is a chance for him or her to acknowledge that mistake and learn from it. This exercise can also be applied nicely to collaborative writing.

3.

Write a memo reporting on the types of ethical dilemmas faced in your field.

Based on the interview described in the first workshop activity above, have students report their findings and relate them to the chapter. Encourage students to add in their own opinions and interpretations for an added learning experience.

4.

Describe a situation of questionable ethics, and prescribe a solution to it.

An easy assignment is to have students identify a situation involving possible ethical dilemmas.

Common choices are commercials or other advertising, political rhetoric, sweepstakes notifications, and spam e-mail. After describing the situation and explaining the ethical problem, students should tell you what could be done to improve the communication ethics.

Distance Learning Assignments

1.

Write a memo comparing two Web sites that represent opposite ends of a divisive issue and focus on the manipulation of words and/or data in each.

Have students find

94

two equally adamant but opposing Web sites related to one hot topic. Abortion, the environment, cloning, and euthanasia: all of these offer plentiful examples online. Make sure that the Web sites represent groups fighting for opposing stances, in contrast to sites attempting to report objective, unbiased information. Have students write you a memo analyzing the sites in terms of word choice, implications, data interpretation, and visual design; require them to draw conclusions about how heated persuasion can turn into unethical “miscommunication” (perhaps a euphemism for lying?).

2.

Participate in an online discussion about poor communication ethics; summarize that discussion, and draw several conclusions about varying ethical views and their implications.

Divide students into small groups—no more than three or four per team.

Assign them to a chat room, discussion thread, or other online communication medium

(even an e-mail list), and ask that they discuss situations involving questionable communication ethics. Encourage students to speak candidly about their own experiences, including what they’ve heard about practices in their future fields; what they’ve seen online, on television, and in print; how they act (and see others act) as students; and how they expect to act as professionals (Will communication ethics be important in their fields? How? Why? Will they set their own ethical standards or expect their employers to set standards for them?). Suggest that team members play a little devil’s advocate when possible. After the required discussion time (from an hour of intense chat time to several days of asynchronous e-mail) has expired, each student should write his or her own memo to you summarizing the discussion and highlighting interesting and/or varying viewpoints. If possible, they might draw conclusions about how communication ethics varies from field to field and/or how their ethical standards have been verified or changed.

RELEVANT LINKS

The Online Ethics Center for Engineering and Science ( http://onlineethics.org

)

Ethics—I Hope I’m Wrong About This!

( http://www.svcc.edu/academics/classes/okeyd/eng111/ethics.htm

)

ISTC Code of Conduct and Professional Practices

( http://www.petecom.demon.co.uk/codecon.htm

)

STC Proceedings—Limitations in Technical Communication Ethics: Mastering

Shades of Gray ( http://tc.eserver.org/13155.html

)

Technical Editor’s Eyrie: Ethics in Scientific and Technical Communication

( http://www.jeanweber.com/about/ethics.htm

)

Center for the Study of Ethics in Professions: Codes of Ethics Online

( http://www.iit.edu/departments/csep/codes/codes_index.html

)

WORKSHEETS

You may wish to reproduce the following worksheets for use in class or as homework.

95

Ethical or Not?

Consider each of the following situations from all possible angles. Be prepared to present logical reasoning to support your decision: ethical or not?

1.

Using information from but not giving credit to a research paper because it hasn’t been “officially” published.

2.

Borrowing your roommate’s old tech writing report

(that received an A) and using it as an exact template for your future assignment.

3.

Rounding up your grade point average to the nearest tenth of a point on your résumé.

4.

Attending an expensive chemistry tutoring session because you know that the tutor has copies of the tests.

5.

Warning your friend about some tricky final exam questions after you take the exam at an earlier time.

96

Pat Cressford Scenario

You are a district manager for a popular retail store, Musicworld. You oversee the operation of the five stores in your two-county area. The manager of your Bryan store is Pat

Cressford. You have worked with him for three and a half years, and the two of you have become friends. You are very proud of Cressford, who was voted 2000 Manager of the Year for the region. He definitely earned the recognition; his sales were up 42 percent over the previous year, and his store’s employee turnover rate had decreased from 33 percent to 12 percent. In fact, you have been hinting around that Cressford should be promoted to the district management level.

Nevertheless, in the last half of 2001 you have witnessed a severe mood swing on

Cressford’s part. He has told you confidentially that his marriage is on the rocks and the kids are caught in the middle of a sticky separation. Unfortunately, his personal problems are interfering with the quality of his work. His frustration and exhaustion lead him to be grumpy and less flexible with the employees. As a result, the employee turnover rate has begun to climb again and customer service is suffering.

You are trying to be patient and sympathetic with Cressford, but the regional manager (your boss), Mandy Meyers, has caught wind of the situation. Meyers directs you (several times) to warn Cressford that his problems are not going without notice, but you keep hoping that everything will work out on its own. Finally, she instructs you to write an intercompany email message to him, today. In the message, you are to inform him that he has three months to either stabilize or reverse the current situation at his Musicworld outlet. Meyers will review a copy of the message, and a copy of the message will be added to Cressford’s permanent employment file. If the problems do not clear up, he will be fired. You must prepare the message without hesitation.

Instructions

1.

Create an audience profile for both your primary and secondary audiences.

2.

Clearly define the objective(s), or purpose(s), of your message.

3.

Explore the ethical implications of your message and how those will affect what you write and how you write it.

4.

Compose the message to Pat, taking into consideration the analysis above.

97

Research Grant Scenario

You are the head researcher in genetics at Jennings-Bradford in Ft. Worth, Texas.

Typical of the research field, you rely heavily on grants (both government and private) to fund your projects. Your current project, an attempt to locate the gene responsible for breast cancer, has been generously funded by the Amon Carter Foundation. When you submitted the grant proposal, you provided the selection committee at the Foundation with a two-year research schedule, including an estimation of how long it will take you to complete and evaluate your experiment. According to your proposal, the expected completion date is April

2002. During the research period, your only responsibilities to the Foundation are to stay within your budget, remain on schedule, and make quarterly reports on your progress. Your approved proposal serves as a contract, or promise, with the committee that you will stay within these guidelines.

Although you have made some especially valuable progress in the last three months, you will not be finished on time. The reason that you are behind schedule is that at the beginning of the experiment, a research assistant made some errors that did not cost much money but were very expensive time-wise. At the time, you were confident that you could make up the lost time; therefore, you did not mention the mistake in your quarterly progress report to the

Foundation. With this additional time, extra cost is incurred in the rental of the building and the payment of the researchers. Therefore, you’ll also need extra money to conclude the work. Where the original grant was for $120,000, you estimate that you will need an additional six months and $27,000 to finish.

Your last progress report, written in November, did not contain any great news. It was generally positive, but you suspect that the Foundation committee really knew that you had no results to present. Last week, you made a major breakthrough and have been able to narrow your gene search dramatically. You are very confident that you will not only be able to finish the experiment in the extra six months but also that you may save hundreds of thousands of lives—if you can finish the research.

Foundation committee members have been aggressively calling regarding looking forward to the arrival of the April deadline. The progress you have recently made is highly technical and would be too difficult to explain to the financially minded committee members. You need to convince them that another contribution and some patience will be beneficial to everyone involved. Unfortunately, you know that past problems with similar situations will make convincing the committee difficult.

Instructions

1.

Create an audience profile for both your primary and secondary audiences.

2.

Clearly define the objective(s) or purpose(s) of your message.

3.

Explore the ethical implications of your message and how those will affect what you write and how you write it.

98

OVERHEADS

The figures on the following pages may be reproduced as overhead transparencies or simply shown on a computer. The following set of discussion questions associated with each of the figures may be used to elicit student reflections on the concepts.

Discussion Questions for Figure 5-1

In what situations can you envision conflicts between some of these ethical duties?

What other ethical considerations could you add to this list? Why?

Discussion Questions for Figure 5-2

Why is each of these unethical?

Aren’t these common practices?

Isn’t the responsibility of verifying information accuracy left to the audience ?

Discussion Questions for Figure 5-3

Consider an example and a counterexample (that disproves) of each philosophy.

If each can be disproved, then on what do we ground our own ethical principles?

99

Your Professional Obligations

To yourself

To your discipline and profession

To your academic institution

To your employer

To your colleagues

To the public

Figure 5-1: Your Professional Obligations

Unethical Communication Practices

Plagiarism and theft of intellectual property

Deliberately imprecise or ambiguous language

Manipulation of numerical information

Use of misleading illustrations

Promotion of prejudice

Figure 5-2: Unethical Communication Practices

A Behavior Is Ethical If…

It would be a good universal behavior

(Kant)

It creates the greatest good for the greatest number of people

(Utilitarians)

It freely sacrifices one’s own selfcenteredness on behalf of others

(Ellis)

Figure 5-3: A Behavior Is Ethical If . . .