Drawing Lessons from Success

Report No. 35041-IN

Reforming Public Services in India:

Drawing Lessons from Success

A World Bank Report

Acknowledgements

This report has been prepared by Vikram K. Chand. It has benefited from several technical papers commissioned directly for the study by Suresh Balakrishan (Making Service Delivery

Reforms Work: The Bangalore Experience), Subhash Bhatnagar (E-Seva in Andhra Pradesh),

Jonathan Caseley (Registration Services in Maharashtra and Karnataka), Prema Clarke and

Jyotsna Jha (Education Reform in Rajasthan), Sangeeta Goyal (Comparing Human Development

Outcomes in Tamil Nadu and Karnataka), Sumir Lal (The Politics of Service Delivery Reform),

Rahul Mukherjee (Telecom Reform), R. Sadanandan and N. Shiv Kumar (Hospital Autonomy in

Madhya Pradesh), E. Sridharan (Electoral Financing), A.K. Venkatsubramanian (The Political

Economy of Public Distribution in Tamil Nadu), and N. Vittal (Anti-Corruption). In addition, this report has profited from papers commissioned for the Shanghai conference on “Scaling up

Poverty Reduction,” SASHD for its work on “Attaining MDGs in India,” and the Water and

Sanitation Program (WSP), New Delhi for its Voice and Client Power (VCP) studies initiative.

Pooja Churamani and Arindam Nandi provided research assistance for this report. Vidya Kamath provided administrative support. Helpful comments were provided by Shantayanan Devarajan,

Chief Economist of the World Bank’s South Asia Region, as well as Shekhar Shah, Kapil

Kapoor, and Stephen Howes of the World Bank. Peer reviewers for this report were M. Helen

Sutch and Jose Edgardo Campos, both of the World Bank; Samuel Paul, Chairman, Public Affairs

Center (PAC); and N.C. Saxena of the National Advisory Council.

Many individuals from several states, including officials, scholars, and activists spent time with the team sharing their views. Without their generous help, this study would not have been possible. We are particularly grateful to P. I. Suvrathan, Additional Secretary, Department of

Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances, Government of India, and R. Gopalakrishnan,

Joint Secretary in the Prime Minister’s Office for providing written comments on this report. We are also grateful to B.K. Chaturvedi, Cabinet Secretary, for hosting a seminar to discuss this report. In addition, we would like to thank the Planning Commission for organizing a presentation on this report to its members. The report has also been presented at seminars organized by the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration, the Indian Institute of

Public Administration, as well as the Center for Policy Research (New Delhi) and an NGO,

Initiatives of Change. The final report has benefited greatly from these discussions.

ABTO

ADC

ADSI

AIDMK

AIS

APM

BATF

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

Association of Basic Operators

Access Deficit Charge

Assistant District School Inspectors

All India Dravida Munnetra Kazagham

All-India Services

Agricultural Produce Marketing Act, MP

Bangalore Agenda Task Force

BCC

BDA

Bangalore City Corporation

Bangalore Development Authority

BESCOM Bangalore Electricity Supply Company

BJP Bharatiya Janata Party

KAS

KAT

KRIA

Karnataka Administrative Service

Karnataka Administrative Tribunal

Karnataka Right to Information Act

KSRTC Karnataka State Road and Transport Corporation

LSA Lok Sampark Abhiyan

MCC

MCD

Metro Customer Care

Municipal Corporation of Delhi

MKSS Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan

MoEF Ministry of Environment and Forests

MoU

MP

Memorandum of Understanding

Madhya Pradesh

MSW Municipal Solid Waste

MTNL Mahanagar Telephones Nigam Limited

NAC

NGO

National Advisory Council

Non-governmental Organization

FBAS

FOI

FPS

GER

GoI

GoK

GoMP

GP

HWSSB

IAS

IIM-A

IIM-B

ISO

ITA

ITC

JP

BMC

BSNL

BWSSB

CARD

CBI

CBPS

C-DAC

C-DoT

CGG

CIC

CICP

CM

CNG

COAI

CPCB

CRC

CRE

CSE

CVC

CVO

DMK

DoT

Greater Mumbai Municipal Corporation

Bharat Sanchar Nigam Limited

Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board

Computer-Aided Administration of the Registration

Department

Central Bureau of Investigation

Center for Budget and Policy Studies

Center for the Development of Advanced

Computing

Center for the Development of Telematics

Center for Good Governance

Chief Information Commissioner

Computerized Interstate Check-posts

Chief Minister

Compressed Natural Gas

Cellular Operators Association of India

Central Pollution Control Board

Cluster Resource Center

Customer Redressal Efficiency

Center for Science and Environment

Central Vigilance Commission

Chief Vigilance Officer

Dravida Munnetra Kazagham

Department of Telecom

DPAR-AR Department of Personnel and Administrative

Reforms (Administrative Reforms)

DRTI

EC

Delhi Right to Information Act

Election Commission

ED

EDB

EGS

EPABX

Enforcement Directorate

Electronic Display Board

Education Guarantee Scheme

Private Automatic Branch Exchange

Fund-Based Accounting System

Freedom of Information Act

Fair Price Shop

Gross Enrolment Ratio

Government of India

Government of Karnataka

Government of Madhya Pradesh

Gram Panchayat

Hyderabad Water Supply and Sewerage Board

Indian Administrative Service

Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad

Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore

International Standards Organization

Indian Telegraph Act

India Tobacco Company

Janpad Panchayat

NTFIT National Task Force on Information Technology

NTP National Telecommuncations Policy

OCMS On-line Complaint Monitoring System

PAC

PDS

PGC

PHC

PIL

PIU

PMO

PRA

PRIs

PSU

PTA

Public Affairs Center

Public Distribution System

Public Grievances Commission

Primary Health Center

Public Interest Litigation

Project Implementation Unit

Prime Minister’s Office

Panchayati Raj Act

Panchayati Raj Institutions

Public Sector Undertaking

Parent-Teacher Association

RAX Rural Automatic Exchange Switches

RGSM Rajiv Gandhi Shiksha Mission

RKS

RPA

Rogi Kalyan Samiti

Representation of the People Act.

SK Shiksha Karmi

SLA

SMC

SR

SRO

SSS

STP

VAO

VEC

VPT

VSNL

WDP

WHO

WLL

Service Level Agreement

Surat Municipal Corporation

Sub-Registrar

Sub-Registrar’s Office

Sanvida Shala Shikshak

Sewerage Treatment Plant

SWC Single Window Cell

SWRC Social Work Research Council

TDP

TN

Telegu Desam Party

Tamil Nadu

TNMSC Tamil Nadu Medical Services Corporation

TRAI Telecom Regulatory Authority of India

TRC

USO

Telecommunications Restructuring Committee

Universal Service Obligation

Village Accountant Officer

Village Education Committee

Village Public Telephones

Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited

Women’s Development Program

World Health Organization

Wireless-in-local-loop

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY………………………………………………………………

Chapter One : Introduction ……………………………………………………………

Chapter Two : Promoting Competition ………………………………………………

India’s Telecom Revolution…………………………………………………………….

Competition in Market Services to Farmers…………………………………………….. i

1

7

7

11

Chapter Three : Simplifying Transactions……………………………………………... 15

Andhra Pradesh’s E-Seva Model ……………………………………………………......

15

Kerala’s Friends Program ……………………………………………………………….

18

Computerization of Land Records in Karnataka ………………………………………... 20

Gujarat’s Computerized Interstate Check-posts………………………………………….

24

CARD in Andhra Pradesh……………………………………………………………….. 25

Chapter Four : Restructuring Agency Processes ……………………………………… 29

State-Wide Agencies …………………………………………………………………….

The Registration Department in Maharashtra …………………………………...

The Karnataka State Road and Transport Corporation ………………………….

City Agencies ……………………………………………………………………………

29

29

32

35

The Hyderabad Water Supply and Sewerage Board ……………………………

Bangalore : Making City Agencies Work ? ……………………………………..

36

38

Surat after the Plague, 1995-2005 ………………………………………………. 43

Chapter Five : Decentralizing Teacher Management ………………………………… 48

The Madhya Pradesh Experience ……………………………………………………….. 48

Chapter Six : Building Political Support for Program Delivery ……………………

57

Comparing Human Development Outcomes in Tamil Nadu vs. Karnataka, 1971-2001 57

Chapter Seven : Strengthening Accountability Mechanisms …………………………. 64

Civil Service Reform : Transfers in Karnataka …………………………………………. 64

Unveiling Secrets : Access to Information in Rajasthan, Delhi and Karnataka ………… 67

Anti-Corruptions Institutions …………………………………………………………… 72

The Karnataka Lok Ayukta ……………………………………………............. 73

Strengthening the Central Vigilance Commission ……………………………..

Public Interest Litigation ………………………………………………………………..

75

77

Chapter Eight : Lessons for Improving Service Delivery …………………………… 80

94 Bibliography

Boxes

Box 1 : Do Indian Voters Reward Performance? The Problem of Anti-Incumbency .......

Ошибка!

Закладка не определена.

Box 2 : Instruments and cases studied in this report ............

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 3 : Gujarat’s Smart-Card Driving License .................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 4: Building Capacity for E-Governance: Andhra Pradesh’s Chief Information Officers (CIO)

Program. .................................................................. Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 5: The Role of Ideas in Reform in Madhya Pradesh ..... Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 6: Community Participation in Hospital Management: MPs Rogi Kalyan Samiti (RKS)

Model ...................................................................... Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 7: Rajasthan’s Experience in Reforming Primary Education in the 1980s and 1990s

.................................................................................

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 8: Social Programs in Tamil Nadu ................................ Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 9: The Tamil Nadu Medical Supplies Corporation (TNMSC) ........... Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 10: The Battle for Transparency: India’s Freedom of Information (FOI) Act ........... Ошибка!

Закладка не определена.

Box 11: Mumbai’s On-line Complaint Monitoring System (OCMS) ....... Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Box 12 : Reinforcing Accountability in Service Delivery: India and Latin America ....... Ошибка!

Закладка не определена.

Box 13 : The Media as a Source of Support for Reform ...... Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Figures

Figure 1 : Improvements in Overall Satisfaction, Bangalore, 1994, 1999, and 2003........ Ошибка!

Закладка не определена.

Figure 2: Aggregate Satisfaction across Citizen Report Cards, Bangalore ................................... 39

Figure 3: Incidence of Corruption in City Agencies, Bangalore

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Figure 4 Gross Enrollment Ratio by Gender (Primary Schools in MP) .....

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Figure 5: Teacher Absenteeism in India ...............................

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Figure 6: Aggregate Transfer Data, Karnataka, FY 2000/01 to 2004/05 ...

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Tables

Table 1 :Average Tenure of MDs: Rural Women’s Development and Empowerment Project

.............................................................................................. Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Table 2 : Average Bribes Paid in CARD and Non-CARD Offices in Rural Districts ......

Ошибка!

Закладка не определена.

Table 3 :Changes in MCC Performance (1999-2002) ..........

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Table 4 : Population Growth in Surat, 1971-2001................

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Table 5 : State-wise Human Development Index: 1981, 1991, 2001 .........

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Table 6 : Literacy Rates, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, 1971-2001 .............

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Table 7 : Selected School Quality Indicators (Primary Schools), 1992-93

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Table 8 : Selected Health and Demographic Indicators, 1971-2001 ..........

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

Table 9 : Appeals under the Delhi Right to Information Act

Ошибка! Закладка не определена.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

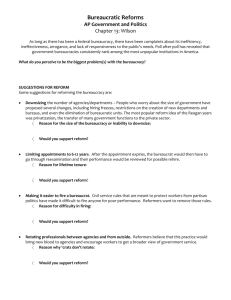

The Focus of the Report: Documenting Successes and Drawing Lessons

This report focuses on successful innovations in service delivery across India. The overarching goal is to identify common factors across cases that explain why these innovations worked. In addition, the report draws lessons from these innovations that might help improve service delivery across sectors and facilitate the transplanting of success stories to other settings. This study examines 25 cases where major reforms in service delivery occurred. The criteria for choosing these cases: All represent some form of institutional reform in service delivery; they range across a variety of sectors, making it possible to discern common threads in reform; there is evidence to indicate a positive impact on service delivery, including surveys, and/or recognition by a credible external organization of significant improvement; and they are stable initiatives in existence for at least two years or longer. In addition, the study examines six cases where innovations were attempted but with less success; these cases are woven into the report to provide some basis for comparison. This study classifies these cases according to six instruments used to improve service delivery: (1) Fostering Competition, (2) Simplifying Transactions, (3)

Restructuring Agency Processes, (4) Decentralizing Teacher Management, (5) Building Political

Support for Program Delivery and (6) Strengthening Accountability Mechanisms.

SOME SYSTEMIC PROBLEMS IN SERVICE DELIVERY

These successes have occurred, despite poor overall outcomes in service delivery and systemic problems that have yet to be resolved.

These successes have occurred in individual services and states, despite an overall context characterized by poor service delivery outcomes. A national survey of major public services

(elementary schools, public hospitals, public transport, drinking water facilities, and public food distribution) by the Public Affairs Center (PAC) concludes that India has done well in terms of providing basic access to such services, but far less well in terms of ensuring their quality, reliability, and effectiveness.

1 A recent study by Transparency International found high levels of corruption in services as diverse as health care, education, power, land administration, and the police.

2 Progress towards achieving the millennial development goals has been slow.

3

There are systemic problems that might explain why service delivery outcomes remain poor on the whole . The civil service is burdening by an expanding salary bill that has crowded out nonsalary spending. Short tenures caused by premature transfers of officials responsible for delivering public services have undermined continuity. Capacity gaps exist in some areas – India, for example, has the highest absolute number of maternal deaths in the world, but only three fulltime officers at the central level dedicated to the task of supervising maternal health programs.

The weakness of accountability mechanisms is a barrier to improving services across the board.

Bureaucratic complexity and procedures make it difficult for the ordinary citizen to navigate the system for his or her benefit. The lack of transparency and secrecy that shrouds government

1 Public Affairs Center (PAC), State of India’s Public Services: Benchmarks for the New Millennium

(Bangalore: PAC, April 2002).

2 Transparency International, Corruption in South Asia: Insights and Benchmarks from Citizen Feedback

Surveys in Five Countries (Berlin: December, 2002). See also, Transparency International/Center for

Media Studies, India Corruption Study, New Delhi: 2005 for more recent data.

3 The World Bank, Attaining the Millennium Development Goals in India (New Delhi: SASHD, 2004).

operations and programs provides fertile ground for corruption and exploitation. Nor is civic pressure for change robust: A national survey conducted in 2001/02 revealed that only eight percent of all respondents were members of a civic association, while only two percent could attest to the presence of an NGO in their area working on the provision of public goods.

4 This finding is mirrored in another national survey conducted in 1996 by the Center for Developing

Societies which found that only four percent of all respondents were involved with a civic association.

5 When the citizenry fails to organize around improving public services, politicians lack the incentives to take the issue seriously.

The lack of accountability in turn provides opportunities for corruption. India ranked in ninetieth place in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) in 2005. Nor is the country well organized to combat corruption: A multiplicity of overlapping anti-corruption agencies, and dilatory legal processes for tackling cases, has made it difficult to bring the corrupt to book. India’s campaign finance regime also has potentially negative effects on service delivery: The unregulated cost of elections – and the lack of legitimate funding sources, including a system of public funding – has created incentives to extract rents from administrative functions, including the delivery of services, to fund campaign expenses or pay back contributors. Despite, these systemic problems, many innovations in service delivery have taken place in different sectors and states with positive results for citizens, as this report shows.

LEARNING FROM SUCCESS: KEY LESSONS

I. The Enabling Environment

(a) The Role of Political Leadership

The vision of the political leadership influenced the kinds of reforms pursued.

The first lesson that emerges from the cases considered in this report is the centrality of the political leadership in triggering service delivery reforms. In Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Karnataka, reforms were frequently a product of the vision of leaders.

6 In Andhra Pradesh, the fact that the state was led by a politician with fascination for technology played a role in propelling e-governance reforms.

7 In Madhya Pradesh, the fact that the leader was committed to vision of governance based on community participation and decentralization clearly influenced the choice of reforms during his tenure in office. In Karnataka, the political leadership sought to transform Bangalore into a leader among cities, using Singapore as a model. At the nationallevel, telecommunications reform was pushed by the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO) as part of a larger developmentalist vision aimed initially at promoting technological innovation and then at strengthening India’s overall competitiveness in the global economy.

4 Pradeep Chibber, Federal Arrangements and the Provision of Public Goods in India, Asian Survey, May-

June, 2004, p. 347.

5 Ibid., p. 347

6 For more on this, see Sumir Lal, The Politics of Service Delivery Reform, Paper prepared for India

Service Delivery Report, (New Delhi: The World Bank, 2005).

7 Chandrababu Naidu with S. Ninan, Plain Speaking, (New Delhi: Viking, 2000).

Bipartisan consensus across party lines facilitated reform; electoral incentives for change.

In Tamil Nadu, the Dravidian parties, which came to power in 1967, were deeply influenced by a common ideology, including the importance female emancipation, the eradication of caste distinction, reservations for backward groups, and family planning to promote development.

Welfarist ideology emerged as a major ingredient of social policy in Tamil Nadu under both the

DMK and the AIDMK in the post-1967 period. Electoral incentives also pushed both parties into supporting similar policies and programs. The defeat of the Congress Party in the 1967 state elections in Tamil Nadu over the issue of food scarcity convinced both the DMK and the AIDMK to create a social safety net through the adoption of a universal system of public food distribution and a noon midday meal programs for schoolchildren and other groups. In fact, the DMK and the

AIDMK engaged in a process of active one-upmanship to extend the benefits of these programs to a wider set of beneficiaries. Opening up the marketing process for rural produce in Madhya

Pradesh to private players was also an electoral winner because the move clearly benefited farmers at the expense of a small group of traders who controlled the official Mandi system.

Programs designed to simplify citizen interaction with government, such as E-Seva and Bhoomi , were also supported partly with an eye to their popularity with voters.

Stable governments with a clear majority in the state assembly were better positioned to implement reforms.

If the ideas of leaders were important for service delivery reforms, political context mattered as well. The fact that Chief Ministers in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh enjoyed stable majorities in their state assemblies made it much easier to carry out reforms. In Tamil

Nadu, the tradition of a strong Chief Minister in both the DMK and the AIDMK, coupled with the fact that no government has failed to complete its full term (with one exception) since 1967, made it easier to implement reform effectively.

(b) Politicians and the Civil Service: Patterns of Interaction

Empowering the civil service through stability of tenure, managerial autonomy, and high-level access to political decision-makers was a crucial factor in the success of reforms.

Chief Ministers committed to reform acted to empower their civil servants to deliver results. The message from these cases is that civil servants when properly empowered by politicians can be transformed into an effective instrument for innovation in service delivery.

Stability of Tenure: Almost all the successful cases studied in this report involved initiatives spearheaded by IAS officers who remained in their posts for at least three years and, in some cases, much longer. Conversely, initiatives that ran into difficulty were marked by great instability of tenure at the top fueled by political pressures to transfer civil servants whose reforms interfered with rent-seeking by powerful interest groups.

Managerial Autonomy: Autonomy helped as well: While status as a corporation or a board conferred definite privileges (for example, the right to retain its own revenues rather than send them on to the treasury; recruit flexibly from the public or private sectors on better terms), effective autonomy stemmed less from a legal charter than a decision by the Chief Minister not to allow meddling in the affairs of a board or corporation.

Political Access: Political leaders granted key civil servants direct access, making it easier for civil servants to resolve issues that might have slowed the pace of reforms. Reporting directly to

the top was clearly the best way to overcome resistance to reform in a range of services. Public signaling of support by political leaders helped protect civil servants implementing difficult reforms.

II. Instruments for Improving Service Delivery

(a) Promoting Competition

Competition improved service delivery outcomes in India’s Telecom Sector, and weakened the monopoly wielded by traders in MP’s state-controlled Mandi system, thus benefiting farmers.

Promoting competition was a powerful instrument for reforming service delivery. The dismantling of the Department of Telecom’s monopoly resulted in cheaper and more efficient calling services; a marked improvement in teledensity, especially in urban areas; and a dramatic increase in the flow of private investment. Similarly, the opening up of rural marketing services to private players operating outside Mandis has yielded gains for farmers and ITC at the expense of traders, who controlled Mandi operations.

Both initiatives were made possible only by strong action from the highest levels of government.

In the telecom case, DoT’s monopoly was progressively challenged by as powerful an institution as the PMO. On a lesser scale, the political leadership in MP was willing to take on vested interests by amending the bye-laws of the Mandi Board and later the Agricultural Produce

Marketing Act to allow for private participation in delivering marketing services to farmers.

(b) Simplifying Transactions

Simplifying transactions through the greater use of e-governance made it easier for citizens to interact with the state. Successful e-governance projects took time to develop, often took the form of public-private partnerships, and needed careful nurturing by the project champion. They also involved changes in business procedures, not just automation.

A second instrument used to improve service delivery was to simplify transactions between government and citizens, using e-governance. Successful e-governance projects depended on high-level political support to overcome resistance by departments not accustomed to horizontal integration of services on a single platform (e.g., E-Seva) or vested interests that might have been sidelined by a new business process (e.g., village accountants in Bhoomi ). An administrative champion to steer e-governance projects with a stable tenure was essential for the success of virtually all projects in this study. Public-private partnerships made a difference, especially in egovernance projects, by raising additional funds to pay for reforms, compelling governments to levy realistic user fees to pay for private sector participation, bringing new technical and management skills to the table, and making it more practical to impose penalties in the event of poor performance. E-governance projects took time to implement fully: four years for E-Seva in

Andhra Pradesh, and seven years for Bhoomi partly because of the digitization challenges in the latter. All e-governance reformers cast the objectives of their projects in terms of reducing staff drudgery and enhancing citizen convenience, rather than eliminating corruption; not a single job was lost in any of the initiatives studied here. Successful e-governance programs combined the use of information technology with major changes in business processes as well

(c) Restructuring Agency Processes

Restructuring agency processes involved change on several dimensions: re-engineering intraorganization processes, empowering senior management through the creation of centralized monitoring systems, improving inter-agency coordination, and developing more effective linkages with civil society. A strong management team was a definite plus.

A Strong Management Team: More than one case pointed to the importance of strong management team to complement the work of the agency head or chief executive of an organization (usually an IAS officer). If the MD lacked the support of strong team, agency turnaround was usually more difficult to achieve.

Reforming Intra-Organization Processes: One common thread running through most of the cases is the fact that serious changes in internal business processes took place. In the Maharashtra

Registration case, process re-engineering preceded automation. In the case of the Surat

Municipal Corporation, steps, such as breaking down silos, empowering deputy and assistant commissioners, and insisting that officers ‘learn from the field,’ constituted a major restructuring in the way business was done. Other examples abound and are discussed in later chapters.

Centralized Monitoring to Hold Staff More Accountable: Centralized monitoring of customer complaints using IT furnished top management with a steady stream of information about performance by middle level managers or front-line staff that could then be used to sanction poor performance. This, in turn, made it impossible for front line staff to connive with lower-level managers to suppress negative information from customers filed at section offices in the case of one water board, for example.

Strengthening Rewards and Penalties: Reformers were able to design a credible system of rewards and penalties by involving private sector players, strengthening monitoring arrangements, and taking action against non-performers. The use of public-private partnership arrangements made it possible to levy penalties on at least private operators, even if government staff could not be easily disciplined for political reasons. In the case of the Surat Municipal

Corporation (SMC), the willingness of successive commissioners to impose penalties on nonperforming officials sent a message down the line that such behavior would not be tolerated.

Several agency heads reported that the award of prizes for good performance by civil society groups or GoI’s Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances (ARPG) played a positive role in boosting staff morale. Some agencies introduced cash bonuses for rewarding well performing units and individual staff members to good effect.

Greater inter-agency coordination: One important lesson that flows from these cases is the importance of breaking down silos. Silos encourage the creation of independent empires within an organization, and render the flow of critical information more difficult. In the wake of the outbreak of plague in Surat, zonal commissioners were empowered to coordinate the work of all departments in a zone; departments had previously functioned as separate entities with little or no coordination between them. The Bangalore Agenda Task Force (BATF) acted as coordination mechanism for all civic agencies, resulting in a significant improvement in city services.

More Effective Linkages with Civil Society: Agency reformers in some cases relied heavily on civil society participation. In the case of Bangalore, the 1994 report card by the Public Affairs

Center (PAC) showed low levels of satisfaction with civic agencies; this, in turn, led to a dialogue with agency heads over reform. By 1999, several agencies had improved significantly and by

2004 even more so. The BATF’s public summits in the presence of the media and the Chief

Minister provided an occasion for agency heads to set reform targets and report back six months later at the next summit.

(d) Decentralization

Decentralization improved the functioning of an important municipal corporation, and reinforced teacher accountability in a major central Indian state.

Decentralization remains a controversial subject: Some have expressed the concern that decentralization without ‘proper safeguards’ can increase corruption and mismanagement. Others worry about local-level capacity constraints to handle additional responsibilities and funds.

Yet, these cases underline the importance of decentralization as a tool for reform. In the urban setting of Surat, the decision to vest zonal commissioners with the financial and administrative powers of the municipal commissioner greatly reduced the flow of files to the municipal commissioner’s office, freeing him up to take the lead on policy issues without getting caught up in red-tape; on the other hand, decentralization in the corporation meant that decisions could be taken more quickly in zones.

In the case of primary education in Madhya Pradesh, decentralizing teacher control to Panchayati

Raj Institutions (PRIs), who were vested with the powers to hire and remove teachers, resulted in one of the lowest rates of teacher absenteeism in India, a remarkable achievement for a lowincome state. The appointment of less expensive para-teachers under PRI control allowed for the extension of a more accountable system of primary education, with local teachers subject to local communities.

(e) Building Political Support for Program Delivery

A consensus across parties facilitated program delivery in Tamil Nadu

Political support is an important pre-requisite for effective program delivery. When politicians care about a particular program, they are more likely to insist on effective implementation by the civil service, including providing autonomy and additional resources. Programs that enjoy political support are better positioned to ward off rent-seeking behavior by influential groups.

Political support was a key factor in why Tamil Nadu outperformed Karnataka in terms of overall human development outcomes between 1981 and 2001. In Tamil Nadu, this commitment was the product of a perception by the two Dravidian parties that social programs would bring electoral returns as well as a common ideological emphasis on welfarist policies. Political support in the form of a bipartisan consensus provided a crucial impetus for Tamil Nadu’s civil service to design and implement a range of inter-locking programs to improve human development outcomes in the state beyond what could have been expected by economic growth alone.

(f) Strengthening Accountability Mechanisms

Reducing premature transfers, fostering access to information, using anti-corruption institutions to generate public pressure against malfeasance, and public interest litigation were some ways used to reinforce accountability.

Reducing Premature Transfers: Short tenures make it virtually impossible to hold officers accountable for their performance and make implementation difficult. Several states have

attempted to grapple with the problem: Karnataka’s has capped overall transfers to about five percent of civil service size through a combination of quantitative caps, computerized counseling in education, and the creation of cadre management committees to reduce political interference.

Fostering Access to Information: Improving access to information is a vital part of any strategy designed to empower clients in relation to providers and the government. The cases of Delhi and

Rajasthan clearly point to the importance of information as tool to enforce accountability: The use of public hearings to examine documents relating to public works has discouraged malfeasance in service delivery in both states. Citizens’ charters are another way to improve access to information and empower citizens provided they are based on extensive consultation, spell out minimum service standards and grievance redressal procedures, and are widely disseminated.

Mobilizing Public Opinion against Corruption: Most state anti-corruption agencies in India are trapped in a numbers game – gauging their performance by the number of people successfully prosecuted – in which they always look ineffectual for reasons beyond their control. The

Karnataka Lok Ayukta not only avoided this trap but reframed what it means to be a ‘successful’ anti-corruption agency in the Indian context. The broad statutory power and institutional strength of Karnataka’s Lok Ayukta were deployed not to prosecute people, but to make corruption in service delivery a potent public issue and compel politicians to take the matter more seriously.

III. Cross-Cutting Issues

(a) The Role of Civil Society

In some cases, civil society groups, along with the media, placed pressure for change on providers and/or the state directly. In other cases, civil society organizations worked in a collaborative fashion with agency reformers. There were examples of reformers working hard to generate demand for change when civil society was relatively weak or inactive.

Civil Society as Pressure: In some cases, civil society groups simply placed pressure on recalcitrant providers and/or the state to compel them to initiate reform. The media also played a major role in generating pressure for reform in several cases documented in this report.

Civil Society as Partner: On the other hand, Bangalore represents a case of collaboration between civil society groups, and city agencies for reform. BATF, for example, provided a convenient monitoring mechanism to track progress on the reform agenda through public summits and technical help for initiatives, such as fund-based accounting and property tax computerization.

Generating Demand for Reform: There were also cases of reformers who actively sought to generate demand for reform as pre-condition for successful change. In Madhya Pradesh, turning over control over new teachers to the community, enlivened local institutions and parent-teacher associations; similarly, allowing district hospitals to collect user fees – and spend the proceeds on maintenance or equipment – sparked community interest in hospital management. Reformers in a water board not only went on a public campaign to sensitize citizens to the city’s water problems but created an institutional vehicle for relaying complaints directly to the MD’s office. In Delhi, the creation of an accessible, yet independent, appeals body made it easier for citizens to secure information from the state government. The Delhi example highlights the significance of proper institutional design in creating spaces for civic participation.

(b) Corruption in Service Delivery

E-governance worked to check corruption when the leadership was supportive. Greater competition was an important factor in curbing rent-seeking.

E-Governance in particular was one tool used by reformers to promote transparency in service delivery. In case the case of land records computerization, the support of the political leadership made it difficult for rent-seekers to defeat e-governance solutions to curb corruption. In other cases, vested interests were able to scuttle computerization efforts in the absence of political backing. Technology by itself is not sufficient to subvert corruption.

Competition played a major in reducing rent-seeking. At the start of the process of telecom reform, for example, the Indian consumer subsidized an overmanned Department of Telecom

(DoT) of some 400,000 employees. The growth of competition resulted in a decline in the number of DoT employees per direct exchange line from 74 in 1990/91 to only 8 in 2002/03 and a marked improvement in service quality along with lower rates. In MP, the government’s decision to allow farmers to contract directly with private players reduced rents accruing to traders as a result of their former monopoly over purchasing in official marketing centers.

(c) Strategy and Tactics of Reformers

Some politicians sought to anchor reforms in past traditions Reformers were able to overcome resistance through promises of no retrenchment in exchange for staff cooperation, finding a place for potential ‘spoilers’ who stood to lose from reform, and activating pro-reform constituencies to counter resistance. Some reforms took less time to implement than others, but in no successful case was a ‘big bang’ approach followed.

Backward legitimacy: Politicians appealed to party traditions to justify change. Anchoring change in the past was one way of giving them greater legitimacy and soothing opposition. The

Chief Minister in Madhya Pradesh, for example, won over his party colleagues to his devolution program by couching it in terms of his party’s traditional support for such programs nationally.

He also recalled the party’s role in supporting the 73 rd and 74 th amendments to the constitution, which provided a constitutional mandate for strengthening the fabric of local government. Both the DMK and the AIDMK appealed to the ideas of a leading figure in the Dravidian movement to justify their programs.

Dealing with staff. Extensive consultation with staff prior to introducing major changes helped reassure employees. Reformers made it clear upfront that no job losses would occur as a result of reforms: Workers were thus not immediately threatened by prospect of reforms. When substantial business process changes occurred, reformers made an effort to partially accommodate potential spoilers: While Bhoomi displaced village accountants from their core function of issuing land records, village accountants still retained a role in verifying land transactions for the

Revenue Department, for example. Reformers also focused on improving working conditions to win employee support; computerization was always cast as an attempt to reduce drudgery and enhance citizen services, and almost never to curb corruption, even if this was its intent.

Activating reform constituencies: Reformers sought to activate potential beneficiaries of their reforms to counter opposition. In the case of rural marketing services in MP, for example, counter-demonstrations by farmers in the wake of a traders’ strike convinced the government not to concede trader demands for a de facto restoration of the old state-controlled monopoly.

How Incremental was Reform?: An incremental approach to reform appears to have whittled away resistance over time in some cases: The dismantling of the telecom monopoly built up slowly over two decades before accelerating in the late 1990’s, for example. Most reforms did not unfold as slowly, but in none of the successful cases was a ‘big bang’ approach followed.

Vested Interests Can be Overcome: These cases clearly show that vested interests can be overcome through a combination of enabling conditions, instruments, and tactics. In Andhra

Pradesh’s E-Seva program, for example, departments went along with a horizontally integrated form of billing that effectively undermined their autonomy. In Karnataka’s Bhoomi program, village accountants, as noted earlier, agreed to a new system of providing land records that undermined their control over this function. In Surat, municipal employees went along with wide-ranging reforms to restructure the corporation after 1994. The Department of Telecom’s opposition to competition gradually eroded under pressure from the Prime Minister’s Office

(PMO). Other cases studied in this report underline the same point: political economy constraints to reform, including vested interests, can indeed be addressed and surmounted.

(d) Sustaining Reforms

Reforms that were popular with citizens survived political transitions; consensus across party lines facilitated reform continuity; sustainability was enhanced when reform was backed up by legal changes and a sound business model.

Even if particular service delivery initiatives were closely identified with a political leader, they could survive the transition from one government to another if they were genuinely popular with citizens. In MP, decentralized teacher management, for example, has continued under new political leadership. In Andhra Pradesh, the popular one-stop service center initiative, E-Seva , remains in place, even after a new party came to power in 2004.

When political parties shared a consensus in favor of a set of programs, sustainability was enhanced. Tamil Nadu is a case where sustainability has been secured because both Dravidian parties, while bitter rivals at the polls, share the same ideological roots. Neither party when in power has attempted to dismantle social programs instituted by the other: A bipartisan consensus stemming from a shared welfarist ideology and a view that dismantling such programs could be electorally disastrous has assured the long-term continuance of the mid-day meal program as well as universal access to cheap rice, even if the fiscal cost of these initiatives has been high.

Codifying reforms into law made them harder to reverse and compelled enforcement as a matter of law. Grounding new institutions in law gave them greater standing and staying power than doing so by administrative fiat alone. For example, the creation of a legally independent telecom regulatory authority has helped enforce a level playing field in the industry, improved the fairness of licensing decisions, and reassured private investors.

When governments allowed user fees to be raised in exchange for better services, or implemented initiatives based on sound revenue models, many times in cooperation with private partners, these were more likely to be viable over time. Cities that had a large revenue base stemming from a dynamic local economy were likely to be able to fund infrastructural improvements than cities that depended more on the state or central governments for financial support.

(e) Transplanting Examples of Reform

Because reforms often developed in a particular context, they were not always easy to transplant.

Promoting dialogue between similar agencies across states; sparking inter-agency competition; and relying on NGO and other networks to spread the good news about successful reforms were the primary ways of transplanting lessons from one setting to another. The Government of India can play a useful role in transmitting knowledge about good practices across states.

Many of the initiatives studied here were driven by their context. Blind copying of initiatives that worked in one setting is not likely to yield similar results in another. Yet, cross-state learning did occur in several ways. In some cases, dialogue between similar agencies across states sparked a chain of reforms: Andhra Pradesh’s program to improve registration services led to Maharashtra initiating a similar program with Karnataka following suit shortly thereafter. In other cases, competition led to a virtuous cycle of reforms: The rise of Hyderabad as a major economic center was a call to action for Bangalore. NGO networks played a role in transmitting good practices across states: report cards first tried in Bangalore will now be conducted in Delhi as well. At times, the Government of India (GoI) pushed states to adopt good practices: One example was

GoI’s insistence that states build community ownership into all rural water supply and sanitation programs after the success of this approach in the Swajal Project in Uttaranchal. The Supreme

Court too helped push states to adopt good practices by, for example, ordering all states to implement a version of Tamil Nadu’s nutritious mid-day meal program in 2001.

More innovative methods of training for government servants to spur innovation and build capacity may make it easier to transplant reforms from one state to another. Andhra Pradesh’s

Chief Information Officer’s program (see Box 4), designed in collaboration with the Indian

Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, has made it easier to train officials in the implementation of e-governance projects; AP’s CIO program could easily be adopted by other states as well.

Disseminating the lessons of success is a key priority

Disseminating these lessons is a priority to break the climate of pessimism that nothing or very little can be done to improve delivery systems, and provide practical help to those seeking to reform service delivery across sectors. One critical issue is whether these lessons need to be applied together as a package to achieve a sustained improvement in service delivery or whether it possible to pick and choose at will. Clearly, a mixture of several instruments applied in the right enabling environment is likely to yield the best results over time. These cases show that improvements in service delivery can take place even in the absence of large-scale systemic changes. There is therefore good reason for confidence in the ability of the state, providers, and clients to come together to make services work in India after all.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY-MAKERS

Creating an Enabling Environment

Chief Ministers play a crucial role in creating a positive enabling environment: Intensive dialogue with Chief Ministers is important for improving services in different states.

Civil servants managing reforms need to be given high-level access to decision-makers to resolve obstacles in a timely fashion. The political leadership needs to signal support.

GoI and state governments need to tackle the issue of short tenures for civil servants by adopting a statutory law to set minimum tenures, permit exceptions only by approval of a statutory civil services board, and track average tenures rates by post over time.

Managerial autonomy needs to be reinforced. Societies can be useful vehicles to shield reformers from political interference and secure the autonomy necessary to effect reforms. Enclaving, however, may create problems of its own by alienating the regular bureaucracy, and is not to be viewed as a permanent solution.

GoI can help create an enabling environment for better service delivery by linking the transfer of funds to states more closely with performance and improving monitoring mechanisms for centrally-sponsored schemes.

Instruments for Improving Service Delivery

GoI and state governments should promote greater competition in service delivery across sectors. Effective regulation can be a solution to the problem of predatory behavior by either government departments or private players.

GoI and state governments can encourage the wider use of e-governance to simplify the interaction between government and citizens. Urban municipalities, district collectorates, and other agencies with a large public interface are prime candidates for business process re-engineering through e-governance. The administration of schemes (including the BPL list across states) should be fully computerized to permit accurate expenditure tracking.

Public-private partnerships work well, particularly in projects with an e-governance component, bringing in new skills and management techniques, financial resources, and greater performance accountability. The use of PPP models should be encouraged.

GoI and state governments could consider conducting functional reviews of serviceproviding agencies to identify redundant functions, legal and procedural reforms, opportunities for clustering, and ways of strengthening linkages with civil society.

Better coordination mechanisms should be created to foster inter-agency collaboration in cities and districts, allowing for information sharing and more effective implementation.

Agency reformers can use the media as an ally to generate public pressure for reform.

Announcing reform plans publicly is a good way to put pressure on staff and managers to implement changes quickly.

Centralized monitoring of public complaints should be made the norm for agencies, thus empowering senior management with the information needed to hold middle management and front-line staff more accountable.

Report cards should be conducted by independent organizations to assess agency performance and widely disseminated.

Access to information legislation needs to be more effectively implemented through better training for officials charged with supplying information, improved records management, and citizen-friendly appeals processes. Civic groups are crucial to the

success of RTI legislation and should be viewed as allies by governments interested in widening access to information. Independent audits of departments could be conducted to pinpoint information that can be routinely released via the internet, for example.

Citizens’ charters are a useful way of disseminating information to clients on how to best use a service. Charters should be formulating only after consultation with staff and users.

Anti-corruption agencies are hobbled by weak investigative powers and overlapping jurisdictions: GoI and state government might consider removing the ‘single directive’ that requires agencies to seek permission to investigate senior officials on corruption allegations. Anti-corruption institutions can play an important in generating public awareness about the problem of malfeasance in government.

Tactics of Reform

Big bang approaches rarely work in the Indian context, but nor do ad hoc carefully sequenced, if incremental, approach is likely to work best. reforms. A

Whenever possible, reforms should be justified by turning to an established source of prior legitimacy (e.g. party traditions). This makes it harder to scuttle them.

The benefits of reform should be widely disseminated to create allies and stir up the beneficiaries of the reform process against vested interests.

E-Governance initiatives are best framed as attempts to improve convenience and cut drudgery, not reduce corruption. Staff should be told upfront that no jobs will be lost.

Sustaining Reform

The best guarantee of sustainability is popularity: independent surveys should be conducted on a regular basis to gauge the effects of reforms on citizens.

Reformers should seek to maximize political support across parties for their initiatives.

This not only helps increase the resources available for a program, but facilitates their long-run sustainability as well. This will involve regular dialogue with opposition parties when formulating and implementing reform initiatives.

Legal changes should be effected to underpin reform, thereby enhancing sustainability.

Reforms should be based on a sound business model (e.g., charging user fees from those able to afford them, professional procurement arrangements etc).

Transplanting Reforms

Strengthening institutional mechanisms to disseminate information about good practices is a key priority. GoI can play a vital role in disseminating information about good practices in service delivery. The electronic repository of good governance practices housed in the Department of Administrative Reforms and Public Grievances (ARPG) should be updated regularly and widely publicized. Similar agencies across states should

periodically share information about common problems and reform processes. Donors and NGO networks can also play a crucial role in this area.

Building greater technical capacity through more innovative methods of training is important in facilitating replication of good practices across states. Andhra Pradesh’s

Chief Information Officers program is a good example for other states on how to go about improving capacity in e-governance, for example.