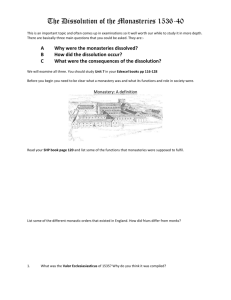

dissolution

advertisement

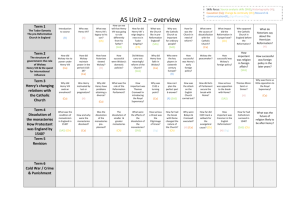

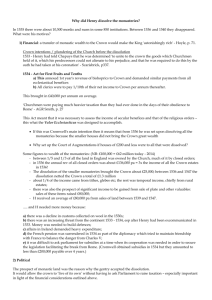

Lecture 7: Henry VIII--Political and Economic Affairs I. Introductory Comments / recapping last lecture II. The pragmatic politics behind the English Reformation A. Repercussions of connections with RCC—as I talked about last time, some of the issues England raised with continued connection to the RCC was the loss of national identity. The Church was used as a foil for tyrannical empire; as a vehicle for the claims of Charles V on the continent. Consequently, connection to the Church meant not only subservience to the Pope and the office of the Papacy, which theoretically held jurisdiction over all national bodies, but to the Spanish in the form of Charles V, nephew to Catherine, and who, as some historians noted, may have had an eye for uniting the two nations—with Spain in the superior position of course. There are mentions of Catherine's letters to her father in which she described England as "his Kingdom" and so the international issue was problematic. The connections with the Papacy raised all of these national concerns B. Socio-Political Ramifications of Separation from Church—there were, of course, many results of the separation from the church, and these results were both positive and negative. The socio-political arguments in part rested on more equitable distribution of lands from a treacherous monastic group. They were avoiding their duties of hospitality, and the funds generated from their lands could go into social development. The Dissolution of the Monasteries also significantly impacted the organization of Parliament. The Lords Spiritual were significantly reduced, and the Lords temporal increased their powers (Jennifer Loach 21-22). After 1539, the lay peers became "clearly the largest and most important" component of the Lords. But, while the dissolution of the monasteries carried with it an air of equitable reorganization, it was very clear from TPTB that they were not seeking to completely undermine the hierarchy or ritual of the Church. Thus, one of the consequences of the dissolution was the emergence of sometimes disparate ideas about how to reject Catholicism (or maintain it). We will talk more about this on Thursday when we examine Thomas More, the Acts written in blood, the Pilgrimage of Grace and various "religious" or "spiritual" rebellions throughout the reigns of the Tudors. Sayegh lecture Dissolution of the monasteries, page 2 C. Economic Ramifications—obviously, the sale of the lands confiscated from the Church generated more popular interest in landownership as well as provided more income for the crown. Thus, Henry was able to generate considerable income from the sale of lands that were now described as "crown lands." The practical application of the Acts of Dissolution was the avoidance of heavy taxation on the subjects in the event (& reality) of conflicts with the continent. Taxation would not be successful & in the minds of Henry's ministers—notably Cromwell—would provide too much resistance in an already tension-filled England. Dissolution and consequent sale of newly formed Crown lands would provide the needed monies to bankroll military conflict. In an age before public finance, this was the most practical (& path of least resistance, according to Beckinsale) manner of national funding. III. The Dissolution of the Monasteries A. The brief history of Thomas Cromwell, legal brain. Thomas Cromwell was born in the late 15th century, around 1485 and died, or was executed, in 1540. He broke away from his family at a young age and worked in a foreign army. He returned to England in 1512, married, started a business, and studied law, pleaded in the courts and was fairly well known, at least in London. He was employed by Cardinal Wolsey (refer to your textbook) in 1520. Under Wolsey, Cromwell was commissioned with developing the proposals to establish a college at Oxford (which already existed) and in Ipswich (in East Anglia, Suffolk). So Cromwell didn't instigate the original dissolutions, he simply helped to make it happen, especially during the years 1526-1528. B. The legal diction of the dissolution—the Dissolution in part focused on the ways in which monies were distributed from the monasteries to the poor. There are many points in the Dissolution acts of the 1530s that focus on the conniving, treacherous, greedy and gluttonous church members, especially in the smaller monasteries. In one of your documents for today, the members of the monastery were moving to a larger one in order to practice "true" religious fervor… This is an important element in the way in which Cromwell organized the dissolution. It was not an abandonment of Catholicism or the nations' spirituality; rather, spirituality was PROTECTED by the dissolution. This is where we see the saliency of the Robin Hood stories. Protecting those who need to be protected and getting rid of bad government and / or leadership. Sayegh lecture Dissolution of the monasteries, page 3 C. The Role of Parliament—During the period of the dissolution, Parliament is referred to as the "Reformation Parliament." We do not think it is a term they called themselves. As mentioned last time, Henry was still working to find an amicable solution with the Church in the late 1520s, even though Cardinal Wolsey was undermining his attempts at annulment. Parliament was summoned By Henry in 1529; first and foremost, it was called on to undermine the credibility of Wolsey and hasten him out of power. This began with a speech by More. But other reasons include Henry's reliance on his subjects to obtain his divorce and to argue for the split with the Church. But the session was not overtly hostile to the Church or to Church organization. Only three of twenty-six statutes dealt with ecclesiastical affairs (Loach 63-64). The second session of Parliament was called in 1531; clergy tried to get a more definitive understanding of praemunire, to no avail. Thus they seemed stuck in an either/or situation. It didn't appear that there were any grey areas.. The third session was called in January 1532. IV. Concluding Comments / setting up for next time Next time we're going to have an in-class visit from a tutor from the WRL. This is supposed to begin promptly at 3:30. We will then jump into the lecture and examine the numerous rebellions that arose as a result of the English Reformation. The past two days we have discussed primarily high-end politics, but we need to go deeper and see why people acquiesced and why they didn't. Did this religious view change over time? We will set up our viewing of a man for all seasons with an excerpt from More's Utopia and an examination of his personal life. V. READING What is the Robin Hood story and when did it emerge? What is the historiography of the RH stories and the Henrician Reformation? How, according to Shield, can the RH stories be read as a cultural expression of people's will? How does Shield draw Henry's personal and political history into the RH motif? How does this relate to Professor Sayegh's argument that Henry was a "practical protestant, not practically protestant"? Dissolution of the monasteries: see review questions after each piece