ethically conflicts

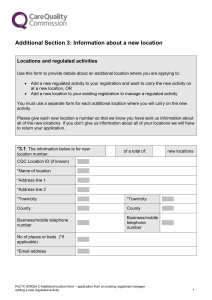

advertisement