CAPITAL CONSTRUCTION

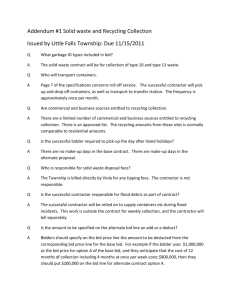

advertisement