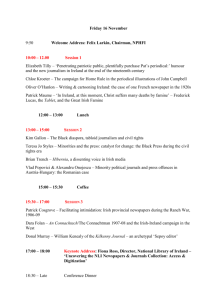

Introduction - Thunderbird School of Global Management

advertisement