Abram de Swaan: World of words

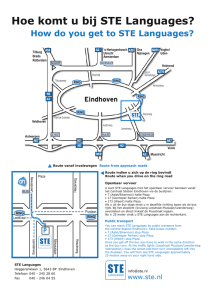

advertisement

Abram de Swaan: World of words (Cambridge: Polity, 2001) Woorden van de Wereld (Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 2002) In the world of sociolinguistics he may be a newcomer, in social science Abram De Swaan (AdS) has a well-established reputation. He is Distinguished University Professor of Social Science at the University of Amsterdam and held the chair of sociology from 1973 until 2001. He was co-founder and dean of the Amsterdam School for Social Science Research (1987-1997) and is currently its chairman. He has published on a wide range of topics. With Words of the World (WotW) he has broadened this range from sociology to the field of sociolinguistics. In a special issue of the Dutch journal “De Gids” AdS wrote that he wanted to show three major points with this book: (1) although the languages of the world differ extremely from each other, the speakers are tied together by bilinguals in a tightly organized system. (2) The position of individual languages in the world system can be expressed by their Q-values (a measure of communicative value). (3) The cultural value of a language is closely related to the total of texts that have been recorded: the collective cultural capital. (De Swaan, 2002) At first sight, WotW presents a refreshing view on the role and history of languages of the world, from a socio-economic point of view. From a sociolinguistic perspective, however, some critical questions can be asked as will become clear in the course of this review article. The book consists of nine chapters. In the first three chapters languages “…are studied from a general social science perspective and it is in this vein that ideas taken from economics have been applied: as part and parcel of a general science of society.” (p. 57) In the first chapter the basic concept of global language system is explained. Starting point is the vision on multilingual speakers as people who are able to bridge the gaps between communities that otherwise could not have been in contact. “Multilingual connections between language groups do not occur haphazardly, but, on the contrary, they constitute a surprisingly strong and efficient network that ties together (…) the six billion inhabitants of the world.” (p. 1) The language scheme is strictly hierchically ordered as in a tree-structure. About 98% of the world’s five or six thousand languages are situated in the lowest part of the tree. Those are the “peripheral”, oral languages, used by not more than 10% of humankind (p. 4). Horizontally any two peripheral Languages can be connected by bilinguals. This is becoming scarcer when speakers of peripheral Languages don’t learn each other’s languages anymore but in stead, they acquire a common second language. Globalization includes vertical in stead of horizontal contacts. Several peripheral language speaking communities may center around one common (and for them: second) language. The second lowest position in the language-tree sketched above is therefore occupied by those central community languages, used in (mainly primary) education and used (both orally and written) by 95% of humankind. Those are often national languages. Language learning occurs upward: speakers of peripheral languages learn a language higher up in the tree, not the other way round. This illustrates the 1 hierarchical nature of the world language system. Both peripheral and central languages (level one and two from below) have native speakers. Native speakers of a central language may learn another L, higher up in the hierarchy. This third level is constituted by the socalled “supercentral” languages, used for long-distance and international communication. Examples of such languages are Arabic, French, Spanish, Hindi. These languages have more than one hundred million speakers each and they connect the speakers of a series of central languages. There is one level higher than the supercentral languages. This level is occupied by only one language, English, that connects the supercentral languages. The position of English is now very strong, but nobody knows how long that will last. It certainly won’t be forever. The global language system, described above, is also called the “galactic model” elsewhere in the book. In later chapters examples of language constellations are discussed (India, Indonesia, Sub-Saharan Africa, South-Africa and the European Union). The world system has a political and an economical dimension (nations and markets). A global society in terms of politics and economics has been recognized for some time; according to the author a linguistic global society has not been described before. In this book, rivalry and accommodation between language groups are explained in sociological and economical terms like language jealousies, exclusion of the unschooled, language as a tool in upward mobility, etc. AdS supposes that languages in isolation and in absence of written texts may have changed rapidly. Linguists believe the opposite: in isolation, languages are conservative. AdS is right if he belongs to the group of people who believe that change can only come from inside a language, he is wrong if externally motivated change (through contact) is stronger (as most sociolinguists do). AdS is a sociologist and therefore looked at with some scepsis by sociolinguists who feel that they are the specialists pre-eminently when language is concerned. Unfortunately, in the Netherlands we are not used to interdisciplinarity on this scale. It is a good thing that AdS deliberately is moving to the field of (macro-) sociolinguistics. He brings in knowledge that sociolinguists traditionally don’t have. However, the other side of the picture is that AdS is not familiar with all relevant fields of sociolinguistics, as illustrated above, and that might be irritating. Had he explained this somewhere in his book, nobody would have a reason to hold that against him. WotW is about competition and compromise between language groups. It combines sociological and economic theory with data from sociolinguistics. The perspective is from a language political sociology and economic angle. This –for sociolinguists unusual- perspective is visible in the use of terms from fields outside sociolinguistics: (Semi-)periphery and core in a world system are macro-sociological terms. Terms like state, nation and citizenship have their origins in political sociology. Generally, exchange between language groups proceeds on very unequal terms. Whether a language gains or loses speakers depends on its position in the language constellation. A dominant language is not the equivalent of a collective good since many people are excluded from learning it. Crucial throughout the book is the communication potential of a language, expressed in the “Q-value”, which is “the proportion of those who speak it among all speakers in 2 the constellation and the proportion of multilingual speakers whose repertoire includes the language among all multilingual speakers in the constellation. People will prefer to learn the language that most increases the Q-value of their repertoire.” (p. 20) The higher the Q-value, the better, the more chance this L will “win”. But I think there is a lot that the Q-value does not cover. For example, it does not say anything about the contradictory values that L1 can have. People can be very proud of their L1, like the Turks in the Netherlands, or they can look down upon it, as used to be the case with Berbers for a long time. The tem value is used frequently in this book. In the index, I saw no references to the term attitude that is closely linked and probably the socio-psycholinguistic counterpart of the more socio-economic term value. AdS admits that exact Q-values are different to obtain since we don’t know languages skills in many languages. I would say: we don’t know that from any language; just like we don’t know exact numbers of speakers of most languages. Q-values based on the number of speakers of a certain language “would do no right to this measure” (p. 39). But even that is impossible to carry out or to calculate for most languages. How hypothetic is the Qvalue? In a reaction, René Appel (Appel, 2002) criticizes the extreme instrumental view on language. I think that this touches the heart of sociolinguistics and it is therefore a serious shortcoming of WotW. Of course, language is to its speakers much more than an objectively measurable economic tool. It has affective value. The author is well aware of this shortcoming but when asked about this he replied that he simply misses the tools to describe affective aspects of language. Every sociolinguist could have told him so before he started. In the second chapter, the political economy of language constellations is discussed. Languages can be seen as hypercollective goods. Economic goods are “consumed” and as a consequence, the more they are used, the less there is left of them. For languages the opposite is true. The more you use it, the more valuable it becomes. Languages have a lot in common with socalled “free goods” (no tickets, stamps etc needed). The more users a language has, the more valuable it becomes, also from and for each individual user. Languages are no one’s property. But does that make them collective goods? If so, there are four conditions that have to be obeyed: 1- nobody can be excluded (true for languages) 2- Maintenance: collaboration of many but not all is required (true for languages) 3- The efforts of a single person are not sufficient (true for languages) 4- Utility does not diminish as new users are added (true for languages). Consistently, AdS consideres language as a “hypercollective” good. A particular language may get more and more learners and speakers, it increases as the number of speakers increases until it is the only spoken L left. The reason why there is quite some stable mulitlingualism is, according to AdS caused by the fact that it is a lot of trouble and effort to learn a new language. I think that there may be other reasons as well, like different levels of importancy. There may be an outside-value attached to the new language, like social mobility or career, but the inside-value may be different; it may have no affective value. It may not be fit to use for stories or jokes. It is the well-known difference between solidarity and power. To sociolinguists and socio-psychologists, these concepts are familiar from the field of, e.g., attitude studies. Again, as was the case with the Q-values, most attitudinal aspects are not considered. AdS concentrates on power and seems to neglect solidarity arguments. 3 The central theme in the third chapter is the conservation of collective cultural capital: the totality of available “texts” in a given language. Texts are ”language-bound products” (p.43) Texts are said to be both oral and written. But the way text is used in this book it mostly refers to written texts like books. In the discussion, two types of strategy are considered: A cosmopolitan (use a widespread language and audience) and a local strategy (restricted language and audience). Use of the minority languages is often defended while use of the majority language is implicit and does not need defence. We are supposed (by AdS) to see the advantages of the wider used L, like globalization, universalism etc. The basic questions that are discussed here are (a) “Under what conditions do authors and speakers prefer free exchange of language-bound products?” and (b) “When will they start to protect their own L-community; when will they resort to collective measures to protect their language?” Authors writing in the prestigious other language may damage the native language by forcing people to read in the other language. The reaction may be protectionism. But protectionism may have the opposite efffect: Disney is more than popular in France, where they tried to keep Anglosaxon influence out; and in Eastern Europe western culture was worshipped in the Soviet period, although it was forbidden. AdS makes a distinction between high and low languages and cultures. Low language is an identity marker while high language is seen as cultural capital (in terms of Bourdieu). Unequal relations of power and prestige between languages in the constellation are the same within a language between formal, informal styles, vernacular, dialects, standard, etc. According to the author rivalry between languages has had little attention. I would say that there is quite some attention for rivalry in studies on language shift and loss. But also in newspaper reports on the position of the majority vs the minority language. It is a very hot topic indeed. Chapters 4 through 8 illustrate the theoretical framework set in the first three chapters. In the illustrations large parts of the world are covered: from India, Indonesia, the African continent, South-Africa and Europe, respectively. these chapters are highly informative in the first place. In chapter four (“The rivalry between Hindi and English”), the author uses Bernsteins concepts of restricted and elaborate code to describe the Indian situation: Restricted code is context-bound language use and found in rural areas,. Elaborate code is more context-free language use by the elites. AdS uses the terms elaborate and restricted codes in his own interpretation. From Bernsteins work, however, we know that every elite uses a restricted code as well; elaborate codes, on the other hand, are not used by “lower” social classes, or, to use AdS’s words: in rural areas. It also has to do with formality; the more formal one can speak, the more elaborate the code. It is a kind of terminology that is strongly associated with stigmatization of the group. For this reason, the terms are not used anymore in language/education contexts (where it was used mostly). The French unitary nation-state served as an example for Asian and African countries, and for India, too, after World War II. The national language has two 4 important functions. The first one is symbolic: it is meant to express nationality and the second function is practical, it is used for communication. For colonizers and nationalists it was clear that one language should be chosen as the national language. But in practice, the choice for one language was difficult or even impossible. Before British colonization, language policy was not an issue in India. More recently, English meant both personal promotion and technological development for the local population. On the other hand, Hindi became the symbol of Indian nationalism in the 20th century, since the other major language, Urdu, was allowed by the British colonizers.Mahatma Gandhi, in his struggle for indenpendence and unification, promoted the use of Hindustani as a unifying language, a popular vernacular with low social status, used for trade, and shared by both the hinduistic Hindi and islamic Urdu speakers. But Hindi purists were too strong and Pakistan became a separate state where Urdu is spoken. Finally, in 1965, Hindi and English became the main languages in India. English is the language that is spoken everywhere in India. Hindi is dominant in the North, while in the South English is more important than Hindi. Like in so many other places in the world, mutual jealousy among groups caused the choice for English as the official language in large parts of the country. Chapter 5 is dedicated to the linguistic situation in Indonesia and the historical developments that lead to the current linguistic state of affairs. Bahasa Indonesia (a modernized version of Malay), the use of which has increased tremendously, bypassed a most important other language: Javanese. Why did Indonesia do so and why did India, on the other hand, reject Hindustani, or did Kenya refuse Swahili as its official language? Aren’t the situations in the three postcolonial countries quite alike? Another question is why Dutch, the former colonial language in Indonesia, disappeared so easily. Contrary to English in India, or French in Central Africa, Dutch was never forced upon the local population. Learning Dutch would make the Indonesians more equal to their rulers. An increase of the Q-value of Dutch was not worth the effort. The rejection of Javanese was not self-evident. It had a long literal tradition and was spoken by about sixty percent of all Indonesians. But Javanese culture had been devaluated as a consequence of centuries of cooperation with the Dutch. However, that happened elsewhere as well (Hindi). Why did they choose Bahasa Indonesia? Javanese is pragmatically a highly complicated language for secondlanguage learners. Changing Ngoko (the low version of Javanese) into a vernacular with national value and abolish Krama (the high version high) would be a revolution but introducing Bahasa Indonesia was a revolution, too! An important reason is the fact that Malay is a relatively neutral trade language. The conclusion of the chapter on Indonesia is that once there is a slight preponderance of one language, its Qvalue will increase exponentially. Like in the other chapters, in chapter 6 (“Africa: the persistence of the colonial languages”) the socalled galactic model is used again to describe the language situation. In the description of the Belgian Congo, it is argued that differences between the languages on the lowest level, the peripheral languages, are exaggerated, in order to hinder the emergence of a unified nationalist movement. What I found striking and unnecessary is the following passage: “The Africans themselves did not 5 mind this distortion too much, as it tickled their narcissistic sense of small differences and allow them to boast their great fluency in languages that after all may well have been, for the greater part, dialects of one and the same language.” (p. 97-98). AdS should know that the difference between dialects and languages often is based on political considerations; linguistically, dialects are not more or less than languages. This is not the only place in the book where the term dialect is used in a rather stigmatizing way, like on page 70 where Hindustani was called a “vehicular, popular language” and later, in the same sentence, probably therefore also “a dialect”. A leading question in the chapter about Africa is: Why have former colonial languages maintained their positions in Africa? The author discusses and illustrates in a very readable and schematic way three types of language constellations: 1- the colonial language is the official medium while more than 75% of the population speak one and the same mother tongue (examples are French and Kinyarwanda in Rwanda; English in Botswana); 2- at least 75% of the population speak the same domestic language which is not always their first language, and the colonial language is the official language (examples are Wolof and French in Senegal; Swahili and English in Tanzania). 3- some countries have several indigenous languages, which never are spoken by a majority (an example is Nigeria, where English is the official language, and Zaire where French is official). French possessions overseas have almost exclusively remained Francophone. From outside this may look like linguistic imperialism but according to AdS, the persistance of French is in each inidividual case due to characteristics of the language constellation. De Swaan suggests here implicitly that the language constellation emerges or exists out of the blue. But to me as a reader the opposite may just as well be true: the current linguistic constellation is the consequence of linguistic imperialism!! In all those countries described in the chapter about Africa there are potential domestic languages but only in Tanzania Swahili has “won”, serving as a national language. In most cases the choice for a neutral language like French or English was based on language jealousy among indigenous languages. The next chapter (7) gives a description of the language constellation in South-Africa. The situation during Apartheid is described, and the changes that took place when Apartheid was abolished. The two most influential languages during Apartheid were English and Afrikaans. Speaking Afrikaans meant to associate with the oppressive regime. Under Apartheid home languages were explicitly considered inferior in all respects. They were taught in the homelands but not meant to get any form of prestige. Missionaries learned and codified the local languages and thus established some kind of standard for those languages. Now, after Apartheid, Afrikaans is loosing its position but to the advantage of English and not the local languages. For obvious reasons, the black and coloured populations don’t want to learn Afrikaans. The line of thought within the ANC is that the choice of one local L would cause jealousy. Therefore, a continuation of the use of English is much safer. It was suggested that Nguni and Sutu be used, artificial languages and both combinations of existing languages. However, the idea did not succeed. English is the preferred language for careers. For local language speakers, their own L has such low status that they prefer to speak English to their children which they don’t master enough. A 6 negative consequence is that children master a very poor version of English when they enter school. In 1993, there were eleven official languages. But there is no practical support to ease translating, there is no actual equal status. The consequence is that the position of English is getting stronger than it already was. The last illustration of a language constelllation, Chapter 8, is the European Union. The subtitle is: “The more languages, the more English”, which is quite revealing Originally, French was the main and most important EU language. From the very beginning, there was a strong rivalry with German. This was particularly the case when the EU consisted of only six countries. But in the end, when the UK and Ireland joined the EU, English won. A very important difference between Europe and other parts of the world described in earlier chapters is that the average speaker in Europe is relatively rich and educated. According to AdS languages in Europe are robust languages. I want to add, however, that we should not forget that there are many languages in Europe that don’t have an official status and therefore lack most advantages associated with official languages, like prestige, standardization, a function in education. Such languages are both indigenous and imported like Basque, Roma, and Berber. In the European language constellation four levels of communication can be distinguished: first the level of domestic communication of which the peripheral (beside other) languages form part. The second level is the level of transnational communication, where English competes with French and German. At the third level, the level of the European Parliament and the European Commission, all official languages of the members of the Union have the same status. The fourth level is the level of the Commission’s internal bureaucracy where there are more or less informally adopted a few working languages. The lower in the hierarchy, the more informal the meetings, and the fewer the languages used. This is where we can see the meaning of this chapter’s subtitle: the more languages spoken, the higher the need for a unifying language which is English increasingly. Although some countires officially are multilingual, like Belgium, societal monolingualism is the rule in Europe, while it is the exception in other parts of the world. State = nation = national language, so it seems in Europe. States are the protectors of the official languages. Law, regulations, administration, education, business, prestige and mass media are all associated with that single language. According to the calculated Q-values, English is the connecting language of the European Union. French and German take the second and third positions in terms of Q-values. Again, as I mentioned earlier, only “hard” considerations are taken into account. Language preference or attitudes are not considered. Dutch children for example, have to learn German and French in Secondary School, beside English. But if they would have had the opportunity to choose, they might choose differently. Languages like Arabic, Turkish and Spanish would turn out to be more popular (cf Extra et at. 2001). According to the author, the Dutch prefer French slightly better than German as a second language. Contrary to what he suggests, I think that has nothing to do with communicative value. France is considered a beautiful language, and France a beautiful country; values that German and Germany are not associated with to a lesser degree by the average Dutch citizen. 7 The linguistic dilemma that Europe has to deal with is: maintenance of all those languages versus successful communication. AdS predicts that the languages will stay separate. But English has become the lingua franca. In Chapter 9, (“Conclusions and Considerations”) it is stressed once again that all languages are linked together by bi- and multilinguals as an unevitable consequence of globalization. One of the messages of the book is that the more languages are competing and fighting for equal rights, the better the chances for English to end up as hypercentral language beside and not in stead of all those other languages. In a multilingual country English stands more chances that in a country with a twolanguage system. As long as this is the case, a small language like Dutch is not in acute danger. English is the hypercentral language. Some of the starting points of WotW are questionable, and I would like to discuss some of them. One is that the Q-value of a language increases when it is taught at school. Just to give an example: although most Dutch citizens learned French and German at school, they don’t watch French and German channels on tv because their command of those languages is insufficient. University students have major problems reading French or German texts although they all finished the highest levels of secondary schooling. This illustrates the gap there is between learning a language and actually using it. Its communicative value exists oly in theory. Another thing is that learning a new language always should be worth the effort, otherwise the language will not be learned. But learning English in the Netherlands is no effort: teenagers watch MTV with pleasure and learn English form watching. Taking it all together, WotW is more descriptive than anything else. The choice for Qvalues to describe relations between languages may be questioned, but for the largest part the book consists of highly informative descriptions of language constellations in different parts of the world from a socio-economic point of view, which is refreshing. At least it will provide us with a new perspective to include in ongoing discussions. The information is not new, though, and the author does not pretend to provide the reader with new facts. Although the choice for a purely instrumental description of the language constellation is far from objectve, the author overtly presents his opinion in the final part of the book (“Considerations”, the second half of Chapter 9). English is the language that serves global communicative needs more than any other language. Elsewhere, AdS argues that sociolinguists are people who want to protect small indigenous people against the extinction of their language do more harm than good: they inhibit the local people to profit from the advantages of globalization by maintaning that old peripheral language, associated with a primitive way of life. Although AdS does not stress this vision in WotW, it can be read between the lines and knowing this, it explains his irritation about protectionism over small and threatened languages. I think, however, that it is rarely the case that sociolinguists defend smaller languages without being asked for it by indigenous people. On the final pages of the book a summary of arguments against English as a hypercentral language is given. To mention some of them: Language experts “plead the cause of the ‘smaller languages’” (p. 188) for reasons of linguistic curiosity, and because no language can be superior to another language. Another argument is that learners of English as a second language always have a disadvantage compared to native speakers of English. But this argument is refuted by the author by pointing at 8 the growing majority of people who speak English as a second or third language who enjoy another advantage, i.e. “access to many more people than any other language could ever afford them” (p. 189). References: Appel, R. (2002): “Kleine talen – grote belangen”. De Gids 165-1: 34-58 Extra, G., T. Mol & J. de Ruiter (2001): De status van allochtone talen thuis en op school. Tilburg: Babylon. Swaan, A. de (2001): Words of the World. Cambridge: Polity. Swaan, A. de (2002): “Natalen”. De Gids165-1: 83-89. 9 Reactie van René Appel in De Gids (165e jrg, nr 1, jan 2002, 34-58): Kleine Talen – Grote belangen (Moeder-)taal is essentieel voor mensen. Er worden oorlogen om gevoerd. Een zaak van leven en dood. Politiek conflict is vaak taalstrijd. Taalverandering: intern of extern gemotiveerd Taalverschuiving: (daar gaat het vaak om in WotW) kan instrumenteel (taal = kruiwagen) of sociaal-cultureel (taal = symbool, identiteit) worden bekeken. Waarom heeft taal zo’n sociaal-culturele functie? Relatie taal/cultuur (Cultuur). En taal is direct uiterlijk waarneembaar, i.t.t. ethische waarden of gedeeld historisch erfgoed/gebeurtenissen. Q-value: alleen instrumenteel; communicatieve potentie (maar dat ontkent AdeS ook niet; hij hecht er alleen geen belang aan). In mijn interpretatie is Q-value maar één aspect in het boek. Revival: meestal goedbedoeld maar niet succesvol Faeroisk, Iers en Hebreeuws zijn uitzonderingen. Taaldood: naarmate mobiliteit, gemengde huwelijken en onderwijs toenemen en isolatie afneemt meer taaldood. Volgens de instrumentele benadering geeft taaldood niks. Tant pis mais domage. Dat is min of meer de benadering van AdS. Maar: neem je aan dat taal eencultuuruiting is dan ligt het anders. Vgl met omhalen van kathedralen of kunstwerken, of met het verdwijnen van dier- en planstoorten. Volgens RA loopt het Nederlands gevaar. Ik ben het daar niet mee eens. Afijn zo babbelt het maar door over de invloed van het Engels op het Nederlands en het gevaar van overschaduwing dat op de loer ligt en waar wij allemaal dapper aan mee doen. Engels wordt steeds vaker gebruikt en het Nederlands ondervindt op lexicaal en ander niveau invloed van het Engels. In dit stuk van het debat ben ik eerder geneigd het met AdS eens te zijn dan met RA. AdS en anderen: tweetaligheid ideale situatie. Taalverandering als autonoom proces? Nee natuurlijk. Behoefte aan taalbehoud moet uit de sprekers zelf voortkomen. Tot mislukking gedoemde experimenten zoals bij Onze Taal (kom met goedNederlandse equivalenten) werken wel in Noorwegenen IJsland. Daar is de bevolking ook superpuristisch. Ik vind eigenliik dat RA niet reageert op het boek van AdS maar meer zijn eigen hangups volgt. Kortom: ik ben het eens met Appels kritiek op de eenzijdig instrumentele benadering van taalverschuiving en ik ben het niet eens met de angst dat Nederlands ten onder gaat aan de invloed van het Engels. 10 NRC artikel: Er zijn maar weinig sociolinguïsten die zich met kleine talen in geïsoleerde gebieden bezighouden. Ik ken nauwelijks voorbeelden; zendelingen in Nieuw Guinea met taalkunidge achtergron (van de VU of Leiden), bijbelvertalers in Afrika (SIL, die linguïsten van GG huize prachtige banen aanbiedt). Het heeft weinig zin om in het Bretons te schrijven als je ook mensen buiten die gemeenschap wil bereiken. Overigens bestrijd ik dat het nooit mensen uit de gemeenschap zelf zijn die zich voor behoud van de kleine talen inzetten. Integendeel. De Friezen strijden voor het Fries, de Basken voor het Baskisch, en de Schotten voor het Gaelic. Onderling is er tussen die groepen (begrijpelijk) solidariteit. De linguïstiek heeft naar mijn weten helemaal niet als taak om taal voor te schrijven maar linguïsten moeten BEschrijven, dat is wat anders. Is het zo dat linguïsten kleine groepen “verbieden” om hun taal te verliezen? Geloof ik niks van. Linguïsten leggen de taal vast, en de angst voor verdwijning komt van de sprekers zelf, in de eerste plaats. Hoe kan je nou zeggen dat multiculturaliteit en meertaligheid los van elkaar staan? Je ziet het toch dagelijks voor je? Het pleiten voor het gebruik van de moedertaal is wat mij betreft vooral door praktische of pragmatische redenen ingegeven: als je ouders dwingt thuis Nederlands te gebruiken terwijl ze alleen een krom soort Nederlands spreken, is dat vragen om problemen. Voed kinderen op met een taal waarin je volledig alles kan uitdrukken wat je wil. Leer kinderen dat ze trots kunnen zijn op wat ze van huis uit hebben meegekregen, of dat nou Nederlands of Berber is. Onderzoek heeft laten zien dat het gebruik van Nederlands thuis succes in het onderwijs in de weg kan staan. Zie de verschillen tussen Turken en Marokkanen in hun prestaties, in hun sociaal al dan niet aangepast gedrag! Kijk naar taalverlies in Australië, Nieuw-Zeeland, Canada: Nederlanders zijn het snelst, omdat spreken van Ndls niet wordt gezien als kernwaarde van etniciteit. Inderdaad: je kunt Nederlander zijn zonder Nederlands te spreken. Maar dat kan je niet van elke (etnische) groep zeggen. Je kunt geen Vietnamees zijn zonder Vietnamees te spreken. Groepen kennen aan taal verschillende statussen toe. 11