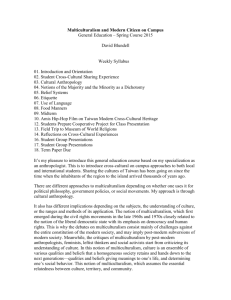

Comparative Geographies of Citizenship Education

advertisement