Reading the US Cultural Past

advertisement

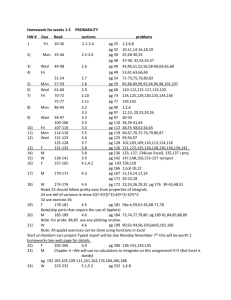

Reading the US Cultural Past Spring 2005 (ENGL 376) Spring 2005 MW 1:15-2:30 Walsh 392 Professor Randy Bass and Matthias Oppermann (Visiting Researcher) Randy Bass bassr@georgetown.edu Car Barn Office: Car Barn 314 Phone: 202 687-4535 Office hours: Available all week by appt. Matthias Oppermann oppermam@georgetown.edu Car Barn 307 Course Description: This course takes an interdisciplinary approach to reading primarily 19th century American literary texts, such as Herman Melville, Rebecca Harding Davis, John Rollin Ridge, and Mark Twain. Our emphasis will be on situating literary texts among contemporaneous cultural artifacts and influences, drawing on other literature, documentary narrative (such as journalism), as well as art, film (e.g., Spike Lee, D.W. Griffith) photography, and other non-literary cultural sources. By looking closely at the relationship between literary texts and cultural contexts, we will spend considerable time exploring questions about what it means to read the past through literature and other cultural documents. Note: This is a four-credit elective. As such it has an additional dimension of activity that will include some primary source archival research (digital and in real archives at the Library of Congress), as well as the option for creating multimedia representations based on the literary and cultural issues. Students interested in teaching and education will have the option to focus final projects on methods for teaching literature based on the approaches we will study. Required Texts: Mark Twain, Pudd’nhead Wilson Herman Melville, Bartleby, the Scrivener and Benito Cereno Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills Stephen Crane, Maggie, a Girl of the Streets John Rollin Ridge, Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta Plus handouts and archival reading throughout Student Work: Web logs (writing and reading) and reflection paper (30% +10%): We will use a web log (or “blog”) throughout the course. This will provide both individual journaling space as well as public space to read and comment on each other’s ideas. Individual blog entries will not be graded but overall participation will be a part of the course. Regular feedback will be provided. You will write a 1 final reflection paper at the end about your blog postings and the progress of your thinking about the course issues. Seminar (30%): There will be four “seminar” weeks where students will run the week. Leading the seminar includes: creating a digital poster, preparing an outline and materials, leading two classes, and writing an essay on some dimension of the seminar, due one week later. Every student (in pairs) will be responsible for one seminar week; everyone else will be responsible for preparing and responding that week (including blog posting). Final Project and Presentation (30%): There will be several options for final projects in the course. The final projects will provide an opportunity for you to develop an interest in greater depth and to develop and demonstrate an understanding of methods and materials by constructing one of several possible products. All three options privilege two key dimensions: The thoughtful analysis and representation of the relationship between literary texts and other cultural texts (and an implicit theory of reading and texts/contexts); and the need to make these issues meaningful through a sense of audience and purpose. The three options for final projects are: (1) Write the editor’s introduction to an edition of a novel. In this option, you imagine producing an edition of a novel (one we read or otherwise) bundled with a set of primary contextual documents; the primary task is to write the editor’s introduction to the edition (for college readers). (2) Create a multimedia exhibition on a set of issues or texts. In this option, you design and execute a multimedia “museum” exhibition around a particular text (one we read or otherwise), cultural and contextual artifacts, and commentary. The focus of the exhibition must be organized around a perspective (if not a thesis). (3) Design a curriculum module or lesson (for whatever age level). In this option, you will conceive, design, and outline a unit or lesson intended to teach a set of issues and texts. Honor Policy The University has a defined honor code and policy, and all students are asked to adhere to the following honor pledge: In the pursuit of the high ideals and rigorous standards of academic life, I commit myself to respect and uphold the Georgetown University Honor System: To be honest in any academic endeavor, and to conduct myself honorably, as a responsible member of the Georgetown community, as we live and work together. You can find the honor policy at: http://www.georgetown.edu/honor/. If you have any questions about the honor code or about your writing please see me. 2 Reading and Schedule Wed 1/12 Introduction to the course. Mon 1/17 Martin Luther King, Jr. Holiday Wed 1/19 Robert Scholes, “Reading the World” (handout); introduction to Bamboozled; Mon 1/24 Spike Lee’s Bamboozled Wed 1/26 Begin collaborative web on Bamboozled and contexts Ethnic Notions Mon 1/31 Bamboozled wrap-up. Develop collaborative web. Poster tool workshop. Wed 2/02 Melville, “Bartleby, the Scrivener” Mon 2/07 Melville, “Bartleby, the Scrivener” and archives (Putnam’s, etc.) SEMINAR WEEK: Melville Wed 2/09 Melville, Benito Cereno and contexts Mon 2/14 Melville, Benito Cereno and contexts Wed 2/16 RB and MO’s ausgezeichnetes Abenteuer Mon 2/21 Presidents Day Wed 2/23 John Rollin Ridge, Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta SEMINAR WEEK: Murieta Mon 2/28 Murieta and contexts Wed 3 /02 Murieta and contexts Mon 3/07 Spring Break Wed 3/09 Spring Break 3 Mon 3/14 Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills Wed 3/16 Davis (and context documents); Jacob Riis, and the real in the late 19th century SEMINAR WEEK: Crane, etc. Mon 3/21 Stephen Crane, Maggie and representations of the real Wed 3/23 Stephen Crane, Maggie and representations of the real Mon 3/28 Easter Monday Wed 3/30 Library of Congress; work on final projects. Mon 4/04 Library of Congress; work on final projects Wed 4/06 Mark Twain, Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins SEMINAR WEEK: Twain Mon 4/11 Twain, Pudd’nhead Wilson and contexts Wed 4/13 Twain, Pudd’nhead Wilson and contexts Mon 4/18 Course synthesis: interdisciplinary readings of literature and culture Wed 4/20 Course synthesis: interdisciplinary readings of literature and culture Mon 4/25 Draft Final Project Presentations Wed 4/27 Draft Final Project Presentations Mon 5/2 Draft Final Project Presentations FINAL PROJECTS DUE: May 11 4 Course Organization: The course is organized into five units or ‘cases.’ All these works are what we might call “social fictions,” fictions about social issues. That is, these texts somewhat readily lend themselves to being read in a documentary way about their historical period (all clustered between 1850 and the turn of the century, with the exception of Bamboozled). But in a sense they are also narratives about social fictions, in that they reveal (on many levels) the ways that cultures imagine and represent themselves to themselves. In each case we will try and uncover the ways that the social fictions or constructs of the era were transformed into narrative fiction, and similarly, how an understanding of these narratives help illuminate our understanding of the U.S. cultural past, and perhaps the cultural present. Case 1: How does Spike Lee’s Bamboozled read the U.S. Cultural Past? How is Spike Lee’s Bamboozled about “America”? What the case is a case of: Spike Lee’s controversial film Bamboozled, about the success of a racially offensive television show, raises interesting questions about the representation of race, the workings of culture in the U.S., and the nature of art and entertainment. The film also makes effective and evocative use of the cultural past, mixing archival and intertextual images to significant effect. Focus text: Spike Lee’s Bamboozled Archives: Cultural artifacts such as memorabilia, cultural and racial representations through early film. Critical resources: Select reviews of Spike Lee’s Bamboozled Marlon Riggs, Ethnic Notions: Black Images in the White Mind (film and text) Readings on “whiteness” Activities: Build a collaborative web on Bamboozled using the poster tool Web logs 5 Case 2: Why is Melville’s social fiction ‘unreadable’? What the case is a case of: Herman Melville was highly attuned to contemporary issues and cultural forms. He was also quite fascinated by the idea of “reading” in its broadest perceptual sense (the reading of meaning and of signs). There is an element of his more social fictions (two of which are “Bartleby” and “Benito Cereno”) where the issue of readability and unreadability plays a huge role in how his narratives manipulate social and cultural meaning. How does his fiction count on “unreadability” as a significant rhetorical device and strategy for cultural critique? How does some literature derive its critical power through complexity, questioning, and confounding? How might cultural forms of a particular place and time, rendered in “literary” language and structures, illuminate cultural complexities, as questions at least if not answers? Focus texts: Melville, “Bartleby, the Scrivener” and “Benito Cereno” Archives: Putnam’s Monthly (1850’s) and other contemporaneous periodicals; Amasa Delano’s Journals (excerpts) Select anti-slavery writing Scholars in Action site (Making Sense of Evidence): Bergmann on Melville Critical resources: Critical essays on Benito Cereno, including Eric Sundquist, from To Wake the Nations and Sarah Robbins, “Gendering the History of the Antislavery Narrative: Juxtaposing Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Benito Cereno, Beloved, and Middle Passage” Activities: Seminar Web logs 6 Case 3: What made reality real in the late 19th century? What the case is a case of: In the second half of the 19th century, one of the most dominant concerns among writers (and other artists and social activists) was the representation of the “real”). This impulse to realism was closely tied both to a sense of progress and of crisis. Narrative fiction changed in the United States in parallel and intersecting ways with other (especially emergent forms of representation) such as investigative journalism and photography. Every era has a particular way of constructing reality as real. How did the late 19th century make reality real through representation? How did literary language, fiction and narrative in particular, try to make claims on representing the real? What authorized these representations of reality? What unsettled them? How does the representation of the real depends on certain conventionalized elements relating to narrator’s authority, voice, evidence, objectivity and subjectivity, etc.? Story: Rebecca Harding Davis, Life in the Iron Mills Stephen Crane, Maggie, A Girl of the Streets Archives: Critical resources: Activities: Ignatius Donnelly, Caesar’s Column Journalism: New York journalism (do this at LC) Jacob Riis, How the Other Half Lives Photography, early film Miles Orvell, “Seeing and Believing” American Photography Alan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive” Critical readings on photography and realism in the 19th century Making Sense of Evidence site: photography Seminar Web logs Library of Congress, group archival research Create collaborative web on New York journalistic representations of the city in the mid 1890’s 7 Case 4: Who was Joaquin Murieta? And what’s he doing in the Disney version of Zorro? What the case is a case of: In 1854, a writer named John Rollin Ridge (or Yellow Bird, his Cherokee name) wrote a novel about a famous “bandit,” Joaquin Murieta, who had committed acts of violence across Gold Rush California. Not only was Ridge’s narrative extremely popular but also it had the effect of creating the figure of Joaquin Murieta as a person of both history and folk culture, representing different meanings to Anglo and Latino California. In 1998, in the Disney movie Mask of Zorro, Joaquin Murrieta makes a quick appearance as the murdered brother of the man who will become the second Zorro. What happens to “Joaquin Murieta” between 1854 and 1998? How do fiction, history, and myth sometimes blur? What does that blurring reveal about the cultural function of some narratives? Why was the Ridge story so popular and so often plagiarized? How can popular literature even if somewhat formulaic be deeply expressive of certain cultural forms? How does the power of narrative give shape to cultural meanings? How do elements of narrative and storytelling “travel” across forms? Focus Text: John Rollin Ridge, The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta Archives: John Rollin Ridge, Joaquin Murieta Bret Harte, “Wan Lee, the Pagan” Wong Sam and Assistants, “An English-Chinese Phrasebook” Documents on citizenship in early California Versions and allusions to Murieta myth Critical resources: Richard Rodriquez, “The Head of Joaquin Murieta” John Carlos Rowe, “Highway Robbery”: ‘Indian Removal,’ The Mexican-American War, and American Identity in John Rollin Ridge’s (Yellow Bird) The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta” Luis Leal, introduction to Iraneo Paz, Joaquin Murrieta Activities: Seminar Web logs Draft final project proposal posters 8 Case 5: Why isn’t Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson about what it’s about? Or is it? What the case is a case of: First, Mark Twain started writing a novel called Those Extraordinary Twins, inspired by news stories of real Siamese twins. Twain was fascinated by the idea of Siamese twins because they invoked all his interests in identity, consciousness, will, and moral responsibility. After completing a short 10-chapter novella about a set of Siamese twins, Twain was profoundly dissatisfied with the result. He discerned however, within the farce, a storyline with more promise. Out of that came the novel Pudd’nhead Wilson, an infinitely more complex, serious, and ‘complete’ narrative about race, identity, and justice; but it is still not the book he wanted to write. That is, Pudd’nhead Wilson is as interesting for the things it cannot speak as the things that it does. Twain’s novel serves as a compelling case of a literary narrative both reflecting and refracting social ideas. Its messiness is illuminating for the paradoxes of American values it reveals surrounding race in the late 19 th century, and the way that race relates to American consciousness about whiteness, violence, science, and cultural order. Story: Mark Twain, Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins Archives: Ida B. Wells, Southern Horrors Images of lynching (photographs and postcards) Plessey v. Ferguson (Supreme Court Decision) Reviews of Pudd’nhead Wilson Images of the stage play and print editions (illustrations) Documents on fingerprinting and racial identity Critical resources: Essays on Pudd’nhead Wilson by Gilman, Sundquist, Robinson, and others Shelley Fishkin, “Mark Twain and Race” Essays on race, lynching, and gender at the turn of the century Activities: Seminar Web logs Revise and develop final project proposal posters 9 10