Diverse Organic Sediments and Stratigraphy in Large Tree

advertisement

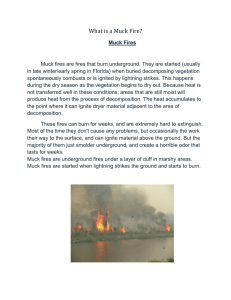

Diverse Organic Sediments and Stratigraphy in Large Tree-Islands of Shark River Slough, Everglades National Park Peter Stone SC Dept. Health and Environmental Control, Columbia SC Michael Ross, Pablo Ruiz, and David Reed Florida International University, Miami FL The tree-islands (“hammocks”) of Shark River Slough in the southwestern Everglades form one of the main assemblages of tree-islands in the regional peatland. There they are seemingly the least disturbed among the large mineralmound-focused major type of tree-island in the peatland. Their importance as emerged to partially emerged sites in adding vegetational and habitat diversity in the encompassing marshland is obvious; additionally they have had a notable archeological and historical role. Important in their own right in the national park, they additionally likely represent lost landscape features of the eastern middle Everglades (CA2B southward) where mounds of sand or limestone also focused the upstream ends of large elongated tree-islands in wide marshes underlain by peat up to a meter or so thick. Related tree-islands lie to the north in CA3. The numerous prominent large tree-islands are elongated roughly N–S, clearly aligned with the direction of sluggish overland flow in the marshes. The exact mechanism for this elongation remains unknown, but has been much speculated. Most of the large elongated (“teardrop” shaped) tree-islands here are twocomponent, with a rounded stand or “head” of more-tropical evergreen trees (true hammock) on the northern end and a long downflow (downstream) “tail” of bayhead forest. The hammock lies above a slight mound in the underlying limestone bedrock and is further raised above flooding by a cap of organic-rich (to peaty) granular sediment. One hammock had an intervening distinct layer of granular carbonate-rich marine sediment of pre-Everglades origin (perhaps a residuum of limestone erosion or perhaps a younger stratum). The bayhead tail lies upon a slight ridge of peat (and muck) and is seemingly unrelated to the topography of the directly underlying limestone, but clearly related somehow to the low mound just upflow. The tail floods in highwater season, though less so than the surrounding marshes. A dense sawgrass marsh can extend this distinct elongation still farther downstream (S) as well as slightly laterally of the tail (E– W) by contrast with the sparser or lower sawgrass or wet-prairie vegetation of the surrounding marshes. Certain large tree-islands lack the hammock head and by their uniform bayhead stand resemble the large tree-islands on deeper peats of the northeastern Everglades. Lacking the mineral mound, their origin and reasons for their location are even more obscure. The rock-mound focus of the more typical tree-islands existed before, during, and after the development of the early Everglades rock and marl marshes and then the peat marshes that now surround the tree-islands. The unfocused tree-islands and the typical tails of all tree-islands seem to have formed only later, during the peatland era. Sediment cores in the head and tail of representative tree-islands, plus a few sites at the periphery and in nearby marshes, reveal an assortment of sediments (some unanticipated) in a fairly complex stratigraphy. Peat or peat-dominated sediment basically prevails (as expected) in the bayhead tails, while peat and a granular forest humus predominates in the hammock heads. But muck—being finegrained organic- and mineral-rich sediment—is extremely common. It is found intermixed with peat in midlevel zones beneath the tails. Muck even dominates some strata, but their upper and lowers boundaries are usually more transitional rather than distinct. Parts of some muck zones have apparently burned to ash. A much different sediment, a granular organic-rich debris, and a sediment modification, incipient cementation, occur in places beneath the hammock heads and their edges (both are probably archeologically related). The abundant muck was unexpected. It is not marly peat, enriched merely with carbonate silt precipitated by periphyton in the marshes. The origin of the silicate-rich muck is yet unknown. The source and mode of transport of the fine mineral matter is the most puzzling, but those of the fine organic matter are unknown too. The muck predominates at midlevels, with purer peat found toward the present surface and in places underlying the mucky sediment. The muck formation and transport possibly relate to a hydrologic and perhaps climatic stage. The emplacement of the muck materials by physical transport very plausibly is related to the process of elongation and alignment of the tails, important components in the widespread “sweep” of Everglades vegetation. Muck in any visible importance was not encountered in the two marsh cores, further adding to the mystery of its origin. Apparent ash layers are found in the peat-and-muck sediment zone beneath two tree-island tails and cover an extensive area in one (occur in two cores 200+ m apart). No other origin seems plausible for this fine, organic-deficient (lightcolored) sediment that contains a little carbonate but is mostly of insoluble mineral (i.e., siliceous). These relict layers are very thick (2.522 cm in three cores) compared to wetted ash from typical Everglades peat fires and must result from the burning of a muck or muck-rich organic layer instead. Typical peat would have had much lower mineral content. Such mucky source sediment underlies or overlies the ash layers, forming an obvious source. Very dry conditions with a severe fire is indicated in each case and these are possible contemporaneous in the two tree-islands (precise 14C dating of this shallow-lying layer is problematic). The pre-peatland era of Everglades wetland evolution is well represented in areas of thicker sediment beneath the tails. Thick marsh marl lies beneath peat in some local solution depressions and in places shows obvious, though subdued, internal stratigraphy, implying environmental changes. These sediment profiles represent the long-term environmental records of the treeislands, including at the top those of recent times. Questions under investigation using paleoecological methods to examine specifics of the floristic and, by proxy, vegetational and hydrological succession, include the following: Are drainage-era shifts evidenced? If so, what were their natures and directions? Prior to that, what was the long-term evolution of these tree-islands? What was the environment of formation of the muck? Additionally, the origin and emplacement of the muck and the shaping and elongation of the tails have strong implication to the whole question of flow and physical transport of solids in the Everglades. Peter Stone, Bureau of Water, South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control, Columbia, SC 29291 Phone: 803-898-4151, Fax: 803-898-2893, stonepa@dhec.sc.gov