CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE

advertisement

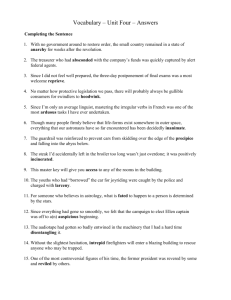

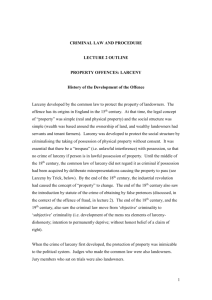

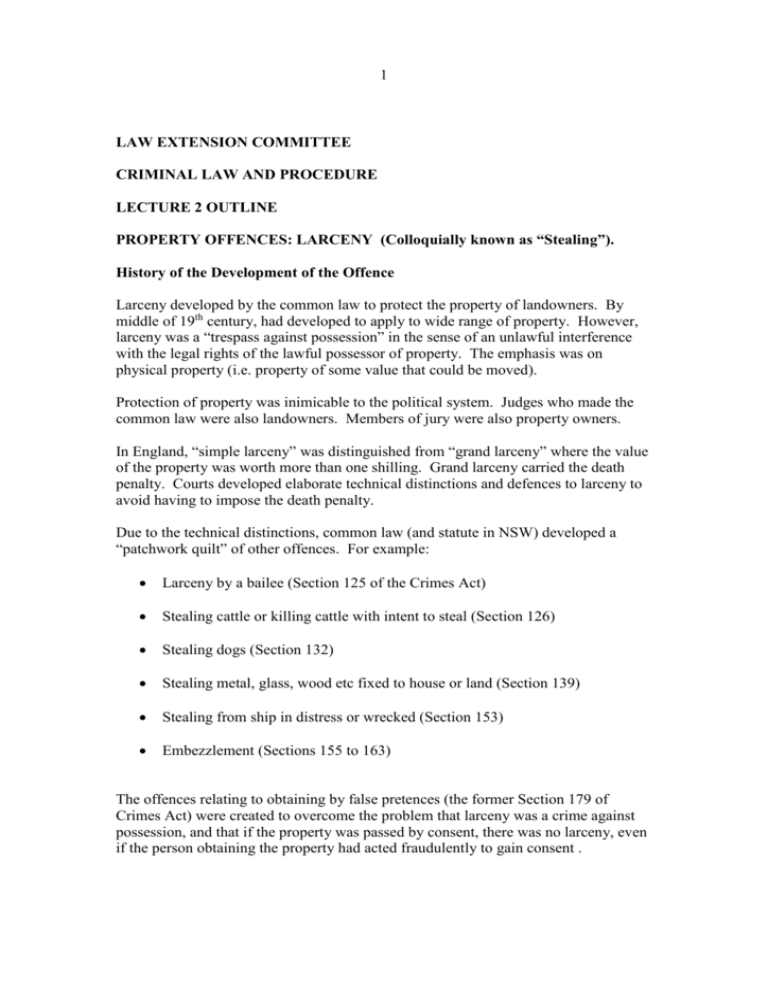

1 LAW EXTENSION COMMITTEE CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE LECTURE 2 OUTLINE PROPERTY OFFENCES: LARCENY (Colloquially known as “Stealing”). History of the Development of the Offence Larceny developed by the common law to protect the property of landowners. By middle of 19th century, had developed to apply to wide range of property. However, larceny was a “trespass against possession” in the sense of an unlawful interference with the legal rights of the lawful possessor of property. The emphasis was on physical property (i.e. property of some value that could be moved). Protection of property was inimicable to the political system. Judges who made the common law were also landowners. Members of jury were also property owners. In England, “simple larceny” was distinguished from “grand larceny” where the value of the property was worth more than one shilling. Grand larceny carried the death penalty. Courts developed elaborate technical distinctions and defences to larceny to avoid having to impose the death penalty. Due to the technical distinctions, common law (and statute in NSW) developed a “patchwork quilt” of other offences. For example: Larceny by a bailee (Section 125 of the Crimes Act) Stealing cattle or killing cattle with intent to steal (Section 126) Stealing dogs (Section 132) Stealing metal, glass, wood etc fixed to house or land (Section 139) Stealing from ship in distress or wrecked (Section 153) Embezzlement (Sections 155 to 163) The offences relating to obtaining by false pretences (the former Section 179 of Crimes Act) were created to overcome the problem that larceny was a crime against possession, and that if the property was passed by consent, there was no larceny, even if the person obtaining the property had acted fraudulently to gain consent . 2 On 22 February 2010, the obtaining by false pretences and forgery offences were replaced by new statutory provisions. In respect of the former ‘obtaining by false pretences’, the major offence is fraud (Section 192E Crimes Act). Movement of objective criminality in larceny to subjective criminality (G.P. Fletcher, “The Metamorphosis of Larceny” (1976) 89(3) Harvard Law Review 496 Codification of Property Offences Theft Act (1968) UK abolished common law larceny and replaced it with a comprehensive code dealing with property offences. Similar legislation was adopted in Victoria in 1974; the ACT in 1985; and South Australia in 2002. In 1995, Model Criminal Code Committee recommended all Australian states adopt the Theft Act model, and replace over 150 offences dealing with fraud, theft and larceny with a code of 20 offences. Penalties for Larceny Section 117. Up to 5 years imprisonment. However: If dealt with summarily, and property less than $5,000.00, maximum penalty is 12 months imprisonment and/or 50 penalty units ($5,500.00). Basic Larceny Definition Section 117 of Crimes Act. Definition of elements of larceny derive from the common law. Elements are: i. Property capable of being stolen; ii. Without consent of lawful possessor (usually owner) of the property; iii. Taken and carried away (Asportation/Appropriation); iv. Dishonestly, without honest belief of claim of right; v. Intention to permanently deprive at time of taking. Actus Reus Types of Property Which Are Capable of Being Stolen Physical property that has some value. 3 Corpses. Kelly (1998) Illegal Property Anic (1993) Types of Property Which Cannot be Stolen Money in Joint Account Croton (1967) Without Consent No consent to person hiding items of clothing and taking them to another part of a department store. Kolosque v Miyazaki (1995) No consent to person using an ‘off line’ ATM to withdraw money from an account that had been closed. Kennison v Daire (1986) Appropriation/Asportation Switching price labels in supermarket Morris (1983) Moving items from one part of a store to another with intention to permanently deprive Kolosque v Miyazaki (1995) Moving items from one part of the employers truck to another Wallis v Lane (1964) Mens Rea Intention to Deprive Owner Permanently Keeping a wallet. When does the criminal intention arise? Mingall v McCammon (1970) Section 118 . Does it remove intention to permanently deprive? No. Must be an intention by the taker to use the property as his or her own, or exercise ownership of the property, even for a short period of time. Foster (1967) Intention to return property after using the property, or replace property, is not a Defence Cockburn (1968) 4 Dishonesty or Fraudulence Peters (1998)- Toohey and Gaudron. What is ‘dishonesty” depends upon context used in the offence. If ‘dishonest’ is used in the “special sense”, trial judge must explain the types of belief sufficient to be “dishonest” in the context of the offence. In such a context, “dishonesty” is to be determined by the application of the standards of ordinary decent people. Also applied in Macleod (2003); However, on 22 February 2010, Section 4B introduced into Crimes Act, which defines test of “dishonesty” as: “...dishonest according to the standards of ordinary people and known by the defendant to be dishonest according to the standards of ordinary people.” Honest belief in a claim of right negates the mens rea: Lopatta (1983). However, there are significant limitations on whether the defendant honestly believes he or she has a claim of right over the property (or the same monetary value as the property in question): Fuge (2001) Contemproraneity of Mens Rea Doctrine of continuing trespass Riley (1853). If there has been a trespass against possession, the trespass continues until the defendant forms an intention to permanently deprive. However, in ‘larceny by finding’ cases, the principle of Thurbon (1848) is that there is no dishonesty if, at the time of the taking, the defendant honestly believes the true owner of the property can’t be found; or honestly believes the property has been abandoned. Doctrine of continuing trespass distinguished in Mingall v McCammon (1970) by consideration of how it interacts with the principle in Thurbon. Bray C.J. held that principle in Thurbon is an exception to the principle of continuing trespass in Riley. Some Categories of Larceny, other than ‘Simple’ Larceny Larceny by Mistake (i.e. property handed over by mistake); Larceny by Finding (i.e. property found by taker, and taker decides to keep the property) Larceny by Trick (i.e. property handed over by ‘consent’, but the ‘consent’ was obtained by deception). 5 Larceny by Mistake Type of mistake. Unilateral or mutual? Bray CJ of South Australian Supreme Court in Potsik (1973). A mistake only vitiates (removes) consent if it is a “fundamental mistake” High Court in Illich (1987)-Concept of “fundamental mistake” which negates consent. 3 types of fundamental mistake: 1. Identity of the transferee 2. Identity of the thing delivered. 3. Quantity of the thing delivered (with the exception of money, where it is presumed that the person transferring money intended both ownership and possession to pass).