Fiction's Impact on Real Life: Lessons from Literature

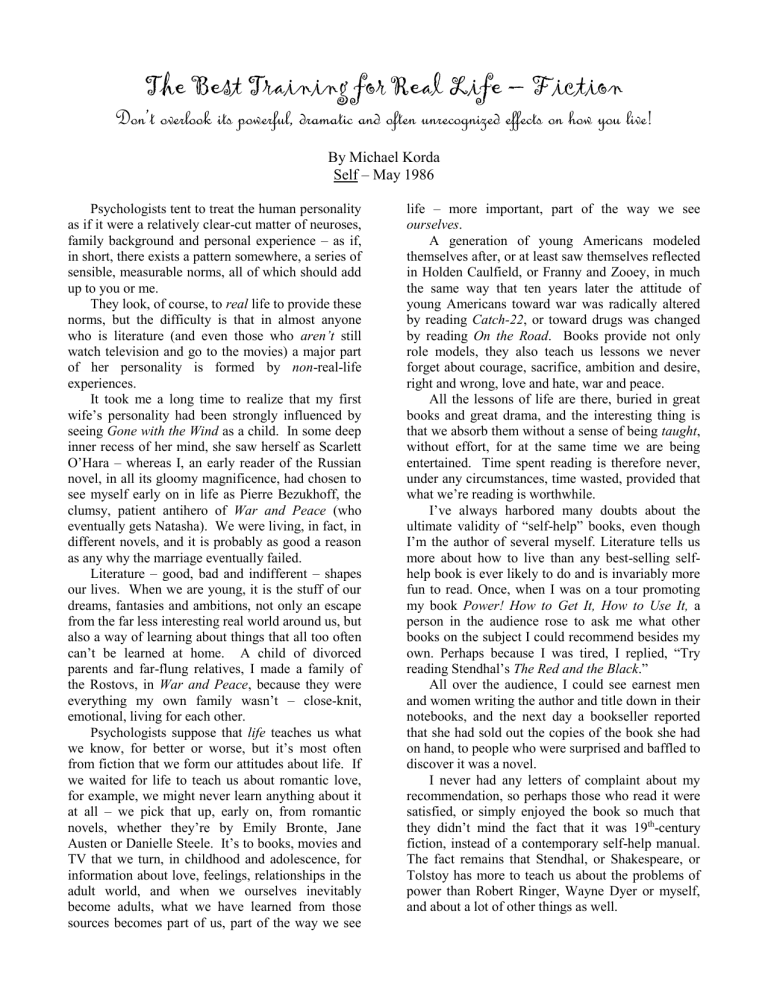

The Best Training for Real Life – Fiction

Don’t overlook its powerful, dramatic and often unrecognized effects on how you live!

By Michael Korda

Self – May 1986

Psychologists tent to treat the human personality as if it were a relatively clear-cut matter of neuroses, family background and personal experience – as if, in short, there exists a pattern somewhere, a series of sensible, measurable norms, all of which should add up to you or me.

They look, of course, to real life to provide these norms, but the difficulty is that in almost anyone who is literature (and even those who aren’t

still watch television and go to the movies) a major part of her personality is formed by non -real-life experiences.

It took me a long time to realize that my first wife’s personality had been strongly influenced by seeing Gone with the Wind as a child. In some deep inner recess of her mind, she saw herself as Scarlett

O’Hara – whereas I, an early reader of the Russian novel, in all its gloomy magnificence, had chosen to see myself early on in life as Pierre Bezukhoff, the clumsy, patient antihero of War and Peace (who eventually gets Natasha). We were living, in fact, in different novels, and it is probably as good a reason as any why the marriage eventually failed.

Literature – good, bad and indifferent – shapes our lives. When we are young, it is the stuff of our dreams, fantasies and ambitions, not only an escape from the far less interesting real world around us, but also a way of learning about things that all too often can’t be learned at home. A child of divorced parents and far-flung relatives, I made a family of the Rostovs, in War and Peace , because they were everything my own family wasn’t – close-knit, emotional, living for each other.

Psychologists suppose that life teaches us what we know, for better or worse, but it’s most often from fiction that we form our attitudes about life. If we waited for life to teach us about romantic love, for example, we might never learn anything about it at all – we pick that up, early on, from romantic novels, whether they’re by Emily Bronte, Jane

Austen or Danielle Steele. It’s to books, movies and

TV that we turn, in childhood and adolescence, for information about love, feelings, relationships in the adult world, and when we ourselves inevitably become adults, what we have learned from those sources becomes part of us, part of the way we see life – more important, part of the way we see ourselves .

A generation of young Americans modeled themselves after, or at least saw themselves reflected in Holden Caulfield, or Franny and Zooey, in much the same way that ten years later the attitude of young Americans toward war was radically altered by reading Catch-22 , or toward drugs was changed by reading On the Road . Books provide not only role models, they also teach us lessons we never forget about courage, sacrifice, ambition and desire, right and wrong, love and hate, war and peace.

All the lessons of life are there, buried in great books and great drama, and the interesting thing is that we absorb them without a sense of being taught , without effort, for at the same time we are being entertained. Time spent reading is therefore never, under any circumstances, time wasted, provided that what we’re reading is worthwhile.

I’ve always harbored many doubts about the ultimate validity of “self-help” books, even though

I’m the author of several myself. Literature tells us more about how to live than any best-selling selfhelp book is ever likely to do and is invariably more fun to read. Once, when I was on a tour promoting my book Power! How to Get It, How to Use It, a person in the audience rose to ask me what other books on the subject I could recommend besides my own. Perhaps because I was tired, I replied, “Try reading Stendhal’s The Red and the Black .”

All over the audience, I could see earnest men and women writing the author and title down in their notebooks, and the next day a bookseller reported that she had sold out the copies of the book she had on hand, to people who were surprised and baffled to discover it was a novel.

I never had any letters of complaint about my recommendation, so perhaps those who read it were satisfied, or simply enjoyed the book so much that they didn’t mind the fact that it was 19 th -century fiction, instead of a contemporary self-help manual.

The fact remains that Stendhal, or Shakespeare, or

Tolstoy has more to teach us about the problems of power than Robert Ringer, Wayne Dyer or myself, and about a lot of other things as well.

I’m sometimes astonished to realize how much of my own perceptions of life are filtered through literature. If I hadn’t been exposed to Hemingway,

T.E. Lawrence and Orwell at an early age, I wouldn’t have left college in 1956 to go fight in the

Hungarian Revolution, and if I hadn’t been sustained there by the notion that what I was doing was essentially a romantic, literary act, I don’t think I would have survived. If I hadn’t read about the grandeurs of the military life, I would certainly not have joined the British armed forces when I was 17, nor been able to look upon that experience as interesting and significant, rather than a painful and time-wasting episode of three years duration, as my family viewed it.

When you come right down to bedrock,

Shakespeare tells us more about jealousy in Othello than we are ever likely to find out by reading a modern nonfiction best-seller on the subject, and

Dickens tell us more about families than we are ever going to learn from the works of modern family counselors. Literature is not an escape from life, it is a way of experiencing life on a larger scale-a way of understanding that what we feel and experience has been felt and experienced before, that our problems are not unique but have been faced by other people, and overcome.

That, in the end, is the most important lesson of literature: that we are not alone in suffering the problems of childhood, or adolescence, or love, or marriage, or pain, or even death; that others over the centuries have gone through the same things and survived. In real life, it is hard to find people who can talk to us about such things-or at any rate who can to us sensibly, frankly, and openly, beyond the usual clichés-but literature is full of just such experiences, from which anybody who can read, can learn .

In the end, great literature teaches us about ourselves . It does not offer us pat, ready-made solutions, like self-help books; it offers examples and life experiences that help us, in good times or bad, to face our own problems.

It is one of the ironies of our present age that increasingly we trust only what is new, based on

“research,” whereas the real truths almost always lie elsewhere. The works of self-help gurus, in the end, are thin fodder compared to Tolstoy, Dickens, and

Balzac, or their more modern equivalents, to the extent there are any. How many people do we know in the new age of materialism (which in so many ways resembles the Twenties) who remind us of

Gatsby, desperately trying to compensate for his inner emptiness with glitzy material success? I can never reread Gatsby without thinking of the number of people I know who are having a lousy time in the middle of their own prosperity and success today, and who don’t know why despite the fact that F.

Scott Fitzgerald understood it perfectly, and wrote about it better than anyone else.

Circumstances change, customs and habits die out and are replaced by others, but human nature doesn’t change, and hence literature is never out of date. That is why King Lear still tells us all we need to know about the perils of old age and pride, and why Oedipus still reads as if it had been written yesterday.

When I was a child, I was often told not to spend so much time sitting by myself with a book. How would I learn anything about life, I was warned, if I spent it reading? As a child, I took these warnings seriously, though I managed to keep on doing just what I wanted to do much of the time. But now, decades later, I can see that the advice was wrong. I learned far more about life from reading books than

I would have from playing in the park or tossing a ball around with other children.

What lessons I did learn in the park and on the playing fields I have long since forgotten, or have been disproved by experience. The lessons I learned from books have stayed with me-and have invariably proved to be true.