Manipur rabies deaths bring to life larger

advertisement

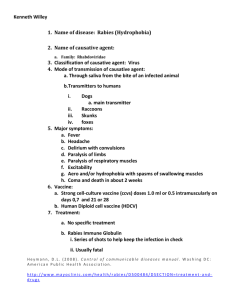

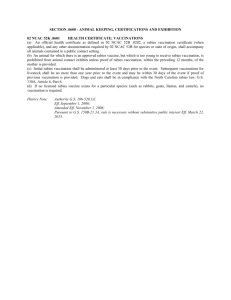

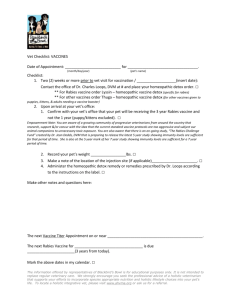

Indian Express (Delhi) 22/03/06 13/s/o/ma Manipur rabies deaths bring to life larger national problem Toufiq Rashid NEW DELHI, MARCH 21 Battling rabies is rarely given the priority as polio, leprosy or TB but 18 deaths reported from Manipur in one week underline a little-known fact: India is the world capital of rabies. Nearly 20,000 people in the country die painful deaths every year due to rabies— the highest incidence in the world. According to WHO, of the 55,000 rabies deaths worldwide in 2004, nearly half occurred in India. The WHO rabies map says the disease is endemic here and every animal bite has the potential to lead to rabies. In 95 per cent cases, the disease is transmitted by stray dogs. With the stray population itself so high, experts fear that the number of victims reported may be far lower than the actual figure. The disease is endemic to the entire country, except island states like Andamans and Nicobar and Lakshadweep. Their geographical location and lower dog population make them relatively immune. But unlike the battle against AIDS, TB or even filaria, there is no concerted government effort to fight rabies, except post-dog bite treatment. “The government policy is to treat every animal bite as rabid and start the treatment,” said Dr R L IchhPujani, an international rabies expert and Deputy Director General, Planning, Health Ministry. Though the official figure is that almost 1.8 million people are vaccinated every year after a dog bite, the vaccine itself is in short supply. The Manipur deaths, which were reported today, happened partly because of the same problem. While the shortage isn’t new, for the past one year, ever since a new tissue culture vaccine was introduced (January 2005), the stocks have dipped lower. Three months back there was a major crisis in Safdarjung Hospital in Delhi, one of the centres for rabies treatment in the Capital. To partly meet the problem, on February 28, 2006, following a WHO recommendation, the government issued an order announcing a new route for administering the vaccine, which would require a lower dosage while maintaining effectiveness. Instead of giving shots in the muscles, the injections are to be now given superficially—on the skin. ‘‘Instead of using 1 ml, the required dosage is now 0.1 ml, and it is as effective,’’ said Dr IchhPujani. ‘‘The new route will ensure more availability of the vaccine and reduce the cost of vaccination...One vial can be used by 10 people compared to one previously,’’ said Dr Bir Singh, professor of Community Medicine, and a rabies expert at AIIMS. The tissue culture vaccine is administered, post a dog bite, in the arm on the first, third, seventh, 14th and 28th day. Earlier, with 1 ml of vaccine being administered very dose, the cost used to come to a steep Rs 3,000 per course (for the imported vaccine) and Rs 1,500 for Rabivax (developed within the country). While availability of the tissue culture vaccine remains a problem, experts warn against a throwback to the old neural tissue option. Though one-third the cost of the new vaccine, the neural tissue vaccine is considered unsafe. Discarded by the rest of the world back in the Nineties, it was in use in India till January 2005. In one out of every 4,000-11,000 people—according to an alert issued by the National Institute of Communicable Diseases—the neural tissue vaccine is known to cause complications leading to paralysis of the brain. Experts believe that the methodology of its administration—14 painful shots in the stomach—scared many people off anti-rabies treatment. Manufactured from the brain of adult sheep, the neural tissue vaccine also had a very short shelf life of six months. There were reports of large quantities being used past expiry date. The Indian Government, however, for long delayed introducing the tissue culture vaccine citing both ongoing trials and its unavailability. The WHO’s blacklisting of neural tissue vaccine finally forced its hand. But the challenge to get people to anti-rabies treatment centres remains. ‘‘A massive awareness drive is needed for that. People need to be told that washing the wound with soap and water helps and that anti-rabies treatment is important,’’ Dr Singh said. Rabies prevention, an official points out, should be a multi-sectoral programme involving the Animal Husbandry Department and municipalities (for vaccination of animals) and the Health Ministry. ‘‘There has to be some sort of coordination,’’ he noted. Another problem is lack of data, with the disease, or even dog bites not notified. One medical journal reported about 500 deaths due to rabies annually in Delhi in 2004. However, even Director, Health, MCD Dr K N Tiwari admits this is far below the actual number. The Infectious Diseases Hospital in the Capital alone admits about 225 cases of hydrophobia per year on an average. But Dr Singh doesn’t fight that surprising. ‘‘When have you seen a public campaign on rabies?’’ he asked. ‘‘A survey in a settlement colony in Delhi showed that people don’t even know about rabies. Same is the case in rural areas.’’ Kids most vulnerable, no vaccination in most cases An official study of 241 rabies at Delhi’s Infectious Diseases Hospital—these were from different parts of north India—came to these conclusions: • Children in age group 5-14 yrs more susceptible (36.7%) • Male-female ratio 4:1 • Animals involved were dogs (96.7%), jackals (1.7%), cats (0.8%), monkeys (0.4%), mongoose (0.4%) • Hydrophobia was present in 95% cases • 93.4% cases did not receive local wound treatment • No vaccination in 91.7% cases, others inadequately vaccinated. Only five had received 10-14 injections