TEXT - Institutional Repositories

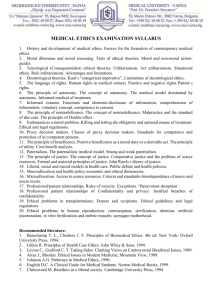

advertisement