Independent Practitioner, 2010, 30, 181-183.

Contractual Issues for Independent Psychologists

Practicing in Health Care Settings:

Practical Tips for Establishing an Agreement

Helen L. Coons, Ph.D., ABPP

and

Julia E. Gabis, Esq.

The number of psychologists working in health care settings such as hospital outpatient

centers, inpatient units, physicians’ offices and community health centers has increased

dramatically over the past three decades. Many psychologists employed in these settings

are formally associated with university and community hospitals, and have faculty

appointments (i.e., clinical, research and/or teaching positions) in a clinical department.

Increasingly, psychologists in independent practice and health care professionals in a

range of specialties recognize the benefits of treating patients with physical, mental

health, psychosocial, and health behavior issues using a collaborative approach. To

facilitate access to psychological services, increase continuity of care as well as patient

outcomes and satisfaction, psychologists are locating their independent practices directly

in health care settings. In addition, health care reform in the United States emphasizes

integrated teams of providers in medical or health care homes which, ideally, will focus

on the prevention of illness and the comprehensive treatment of health, mental health and

health behavior issues. This brief paper identifies practical and legal issues to consider

when locating an independent psychology practice within medical settings such as

internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology, reproductive

endocrinology, oncology, surgery, physical therapy and dental offices.

To build a successful collaborative relationship, health care providers, their office

staff and the psychologist should identify and clarify their expectations at the outset. The

time spent carefully discussing the terms of a collaborative arrangement will build

communication between and among all the stakeholders, reduce surprises, and foster the

collaborative relationship necessary for the effective care of patients and families. Once

the medical office and the psychologist have reached consensus on the arrangement, a

written agreement should be drafted and signed to confirm the terms of the arrangement.

Both parties are well-advised to obtain legal counsel familiar with health care law and the

particular legal constraints on such arrangements to ensure that the agreement accurately

reflects both the agreed-upon terms and complies with federal and state laws and

regulations.

While the final content of agreements will likely vary, most should address the

following issues: 1) the term of the agreement and grounds for termination: 2) the cost

and schedule for use of the space; 3) patient referrals; 4) insurance coverage(s) and

documentation; 5) confidentiality of patient records and propriety matters; 6) storage and

ownership of patient records; 7) use of office resources; and 8) marketing concerns.

These terms are discussed below.

1) Length of the Agreement and Termination. The agreement between the

medical practice and the psychologist should provide for a specific term -- preferably

at least one (1) year. It should also identify the grounds for ending the agreement during

the term and the mechanism for termination at the end of the term. For example, most

agreements will automatically rollover for an additional term unless one party provides

the other with ninety (90) days written notice prior to the end of the term.

2) Cost and Flexibility with Space. While some physicians and/or other health

professionals may control the cost of the space, in university settings or corporate-owned

practices, the cost will likely be determined by management based on the amount of

space and the number of providers using the space. Most offices are priced on the basis

of a unit cost per session – which in the medical setting is often a four (4) hour block of

time (e.g., 8 am to 12 pm, 1 pm to 5 pm or 5 pm to 9 pm), and by the amount of space to

be leased. Often, rates for space in medical offices are higher for physicians who require

more resources (e.g., receptionist, nurses and medical assistants, exam room supplies, and

support for patient scheduling and billing). In contrast, psychologists typically need only

a consult or exam room to see individuals, couples and/or families; phone access to

contact patients, colleagues, and insurance companies; a copy machine for limited

copying of patient information and materials; access to the internet; and a receptionist to

greet patients. In any event, in order to avoid violating federal and state laws, the cost of

the space should be based on the fair market value of the space and resources to be

utilized, and should not take into account or be based upon the value of any potential

referrals between the parties

Space rental may involve a designated space such as a consultation room that

could change depending on the day as well as the number and types of providers who are

also in the office. Rooms may change when physicians, nurse practitioners or other

providers need to do procedures (e.g., exams, minor surgeries, ultrasounds, EKG’s,

injections, etc.) or nurses, nutritionists, genetic counselors offer patient education, etc. In

other offices, psychologists may just use an exam room to see patients. Flexibility

regarding room use allows the medical office to run more efficiently and to accommodate

health care providers and psychologists with changing schedules. Many patients, couples

and families appreciate seeing a psychologist in a familiar medical office which holds

less stigma than a traditional psychotherapy setting. Other patients, who require

consistency in the therapy environment, may not respond well to being seen in different

rooms. Furthermore, some individuals may not feel comfortable seeing a psychologist

routinely in exam rooms when a consult room is unavailable. Furthermore, if the

psychologist has a strong interest in furnishing or decorating an entire office or is

uncomfortable with the hectic pace of a medical office, locating a practice in another

health care professional’s or organization’s space may not be a good fit. These

considerations should be identified in the negotiation process and addressed through the

agreement.

3) Patient Referrals: The agreement should provide that it is not intended to guarantee

patient referrals and that fee-splitting between the health care provider(s) and the

psychologist is not permitted. Providers may refer patients to any qualified mental health

professional, including other psychologists, psychiatrists or social workers in the same or

outside the office. More likely than not, psychologists in a shared setting will receive

referrals and will be asked to help with outside referrals. Patients often need a referral

within their insurance network if the psychologist is not on their panel; prefer to seek care

closer to work or home; have time constraints related to work or childcare which may not

match the psychologist’s schedule; or have treatment needs which require expertise

beyond the psychologist’s scope of practice.

4) Insurance coverage: The psychologist should maintain professional liability

insurance in amounts required by state law, by the health care provider or parent

organization, and/or recommended by a trusted insurance company or broker (whichever

is higher). Landlords often require tenants (and sub-tenants) to have a general liability

policy to cover non-professional claims (e.g., an accident on the premises, loss of

property due to fire). The landlord may also require that the psychologist name the

landlord as an “additional insured” on the insurance policies. This request may be

accommodated through the broker or the insurance company.

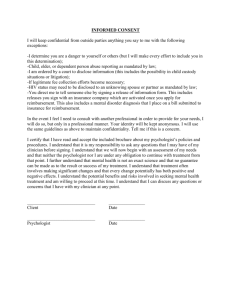

5) Confidentiality: Independent psychologists who are not employed by a health system

or health care practice will likely not have access to a patient’s medical record (i.e., either

the paper chart or the electronic medical record). However, communication about

patient’s health, mental health, psychosocial status, and health behavior as well as the

treatment recommendations is greatly facilitated when care is provided in the same office

and when the psychologist routinely sends brief consultation and follow-up reports

(Frank, McDaniel, Bray & Heldring, 2004;Ruddy, Borresen & Gunn, 2008). Under any

circumstances, appropriate authorization to release health and mental health information

must still be obtained in a manner consistent with federal (i.e., HIPAA) and state laws as

well as the requirements of insurance companies. For example, even if you physically

practice in the same office space with health care professionals, you still have to obtain

written permission to correspond with providers about patients’ mental health or health

psychology care. Consequently, psychologists will need to use their own consent and

release of information forms; and a paper or electronic charting system. Recent federal

legislation will increase the use of electronic medical records (i.e., EMR) for providers

and systems, and will hopefully greatly facilitate communication across the health care

spectrum, including psychologists (Ruddy, McDaniel and Coons, under review).

6) Storage and Ownership of Patient Records: The agreement between the health

practice and the psychologist should provide that all records remain the property of the

psychologist whether maintained by the psychologist either on-site in a locked space or

secured elsewhere. If the psychologist moves his or practice from the health

professional’s office, the records remain the property of the psychologist. In addition, the

records must be maintained confidentially for the period of time required by law. When

there is a concern about providing a copy of records to a patient or in response to a

subpoena, court order or other request, consult in advance with a knowledgeable attorney

(Pope & Vasquez, 2007).

7) Resources: The agreement should specify access to office resources needed to

facilitate patient care. It is helpful to include the office manager during discussions of

work with office staff such as receptionists so that everyone has shared expectations. For

example, while independent psychologists working within a health care setting will likely

do their own patient scheduling and billing, the office receptionist will need to greet

patients. It is essential to discuss what is expected from office staff when new and

returning patients come in for an appointment. Will the staff give new patients intake and

assessment forms? Will the staff bring patients from the waiting room to the consultation

or exam room or will the psychologist escort patients to the office? In addition, it is vital

to negotiate access to technology such as: use of telephones for local and long distance

calls related to patient care (cell phones are not always reliable in many health care

offices); copy machines for patient insurance and other clinical information; use of a fax

machine; and a computer with internet capacity for clinical care, provider

communication, patient education materials and for EMR. It is also helpful to negotiate

limited space (e.g., a file drawer) to store intake forms, patient education materials, and

other testing or clinical tools necessary for the evaluation and treatment of the specific

populations served.

8) Marketing and Professional Independence: The agreement may include language

to provide for the marketing of collaborative programs, and for the protection of

proprietary materials for either the health care practice as well as the psychologist. In

addition, the agreement may specify how the psychologist can list the office address on

business cards, letterhead, websites, etc. to avoid the appearance of being part of the

medical practice. This is important as part of the effort to ensure that patients are not

confused by the office-sharing arrangement and are clearly advised that the psychologist

is not employed by the medical practice. Some agreements may require that patients

seeing the psychologist in the medical office sign a statement confirming that they

understand that the psychologist’s care is not overseen or dictated by other health care

providers in the practice. The agreement may also indicate that the psychologist is

permitted to see patients on site who were referred by health professionals or sources

outside the office and who are not patients of the specific practice.

Concluding Remarks

Before signing an agreement to see patients in a shared health care setting, a

psychologist should retain an attorney with expertise in health care law/licensure

requirements to review the agreement to ensure compliance with applicable federal and

state laws and regulations. Requirements will vary from state to state. Other issues not

discussed in this brief summary may be included in the negotiation and agreement.

Psychologists in independent practice will increasingly work in varied health care

settings in urban and rural areas to improve access to mental health and health

psychology services as well as patient outcomes and satisfaction. This paper is designed

to assist in developing successful collaborative agreements to facilitate patient care and

health professional communication.

References

Frank, R.G., McDaniel, S.H., Bray, J.H., & Heldring, M. (2004). Primary care

psychology. Washington, D.C., American Psychological Association.

Pope, K.S. & Vasquez, M.J.T. (2007). Ethics in psychotherapy and counseling: A

practical guide. San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons.

Ruddy, N.B., Borresen, D.A. & Gunn, W.B. (2008). The Collaborative Psychotherapist:

Creating Reciprocal Relationships with Medical Professionals. Washington, DC:

American Psychological Association.

Ruddy, N.B., McDaniel, S.H. & Coons, H.L. (under review). Electronic health records

and their implications for psychologists.

Helen L. Coons, Ph.D., ABPP is a clinical psychologist and board certified clinical health

psychologist, and is President and Clinical Director of Women’s Mental Health

Associates, Philadelphia. Through her independent practice, she and two colleagues

rotate to several women’s primary care, obstetrics and gynecology, reproductive

endocrinology and oncology settings on a weekly basis. She also provides consultation to

psychologists interested locating their practice in health care settings. Correspondence

regarding this article may be addressed to her at hcoons@verizon.net.

Julia E. Gabis, Esq., Julie E. Gabis & Associates, is an attorney in Conshohocken, PA.

Ms. Gabis has concentrated her practice in health law since 1980 and has lectured and

written frequently on a range of health law topics.

The content of this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal

advice.

Copyright 2010, Helen L. Coons, Ph.D. and Julia E. Gabis, Esq.

All Rights Reserved