Sustaining Estuary Health through Trans

advertisement

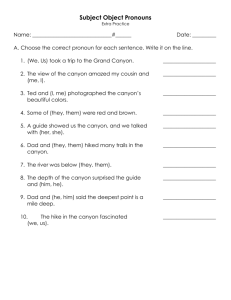

Trans-Border Trash Tracking Waste Management in the Tijuana River Watershed A research proposal submitted to the Urban Studies and Planning Program Senior Sequence Class of 2011 University of California at San Diego Jennifer Leonard USP 186/Section A04 Nov. 4, 2010 Email: jhleonard@ucsd.edu Abstract This proposal outlines case study research on solid waste pollution in the Los Laureles Canyon of Tijuana, Mexico, a sub-basin of the Tijuana River Watershed. Current research on solid waste pollution suggests that although Mexico has adopted environmental protection policies, a lack of local ordinances and policy enforcement contribute to the problem of uncontrolled canyon dump sites. This raises two fundamental questions: Are these canyons a source of waste impacting U.S. wetlands and beaches? And what part does the global economy play in the inconsistency between national environmental policies and regional planning? Through direct observation in the field, this study will document uncontrolled open dumps and track trans-border waste-flows in the Los Laureles Canyon. The study will also analyze the effects of economic globalization on regional planning. Evidentiary research data will be shared with Mexico and U.S. officials. Ultimately, this case will contribute to literature on watershed and waste management in U.S.-Mexico border regions, provide impetus toward policy solutions and prevention ordinances in Tijuana, and promote positive environmental changes in the Tijuana River Valley. Key terms: waste management, watershed management, environmental policy, regional planning, U.S.- Mexico border impacts Introduction/Background Waste management affects everyone, regardless of geographic or political boundaries. As stewards of planet Earth, we must consider and reconsider the consequences of throwing our Leonard 2 trash away because ‘away’ is not an actual destination. Practicing sustainable waste disposal and planning for waste management is critical because it equates to protection and preservation of ecological resources. An investigation of uncontrolled open dump sites in Tijuana’s Los Laureles Canyon will produce an evidentiary record that will serve as a vehicle to changing waste disposal regulations on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border. The elimination of these dump sites is crucial to sustaining the health of the Tijuana River Watershed and to protecting the habitats and species of the Tijuana River Valley and its neighboring wetlands, beaches, and open waters. Los Laureles Canyon in Tijuana, Mexico is a 7 square mile sub-basin of the larger 1,750 square mile Tijuana River Watershed (Romo 2010). The canyon is shaped by unstable alluvial hillsides that have become increasingly degraded over the past five years. During this period of rapid urbanization, Los Laureles has become home to more than 100 uncontrolled open dump sites from which debris of all classes flow directly into the Tijuana River, the National Estuarine Research Reserve (TRNERR), and the adjoining California coastline. At its high-point, the Canyon’s elevation is 700 feet above sea level (Wright, et al. 2005). Elevation combined with unstable soil and a two mile proximity to the California coastline make this canyon an area of particular interest and concern to watershed and estuary managers because during coastal storms the canyon drains directly into TRNERR acreage (Romo 2010). Restated, Los Laureles is a significant source of waste and sediment flows in the southern end of the Estuary and surrounding coastal habitats; according to SEDOSOL, Mexico’s Secretary of State, 33% of all solid municipal waste in Tijuana is disposed of in uncontrolled open dump sites (Good Neighbor. 2010). Efforts have been made to contain these wastes in sediment-basins; however, waste flows now surpass basin capacity. A more sustainable solution would be the elimination of open dump sites in this watershed sub-basin (Romo 2010). Leonard 3 Environmental and financial costs of waste intrusion at the Tijuana River Estuary have escalated over the past five years. Multiple habitats and species are continually at risk. And annual clean-out of estuary sediment basins has surpassed the million dollar mark (Peregrin.2010). The primary goals of this project are to provide lawmakers with a scientific record of the debris-flows from Los Laureles Canyon to TRNERR and to eliminate the existence of uncontrolled open dump-sites in Tijuana’s Los Laureles Canyon; thereby, creating a sustainable and cost-effective alternative to the costly annual maintenance of coastal wetland habitats and the sediment basins that protect them during coastal storms. This research project is important because it is a necessary first step in the process of implementing new waste disposal policies in both Tijuana, Mexico and the United States. In order to strengthen anti-dumping laws and enforcement in the border region, a scientific record of the refuse problem must first be produced. This research project aims to track and record the flow of point-source waste debris in the Tijuana River Valley from the Los Laureles Canyon to the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve (TRNERR) in Imperial Beach, California. GPS coordinate locations of each canyon dump site will be logged into a database in addition to attributes of dump-site debris, slope conditions, and land-use classifications. Research results will be mapped using ArcGIS software and will become foundational evidence for legislative and regulatory change. By project’s end, stakeholders will gain insight into storminduced pollution flows, international resource management, and cross-border waste management (Romo 2010). Leonard 4 Conceptual Framework/Literature Review The conceptual framework for this study is rooted in scholarly research that examines the causes and effects of border-region pollution. Literature review from the field of planning reveals that one cause of disconnect between national and regional policies is the effect of globalization. Oscar Sosa, for example, examines how “globalization processes are changing the roles of borders around the world” (Sosa 2008, 170). By focusing on the San Diego-Tijuana border region, Sosa’s study analyzes how national policies affect border regions and how border regions affect the nation by limiting “the scope of institutions within a national territory.” This means that planners on both sides of the border are subjected to the conflicting goals of multiple levels of government (Sosa, 171). Border regions are “interdependent,” and the effects of globalization on economics, urban planning, and environmental issues can be felt in both San Diego and Tijuana: Border regions thus gain some independence from their national capitals when it comes to policy, and become more likely to work with their neighbors across the border in developing economic, institutional, and public infrastructure. Supranational political and economic agreements such as the European Union and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) help consolidate these processes. These agreements also provide a national policy framework that can lead to policies that directly affect the planning arena of border regions (Sosa 2008, 170). Post NAFTA, Tijuana is home to approximately 1/3 of the more than 3,000 maquiladoras in Northern Mexico which employ 30% of Tijuana’s population; these businesses are all located in the border region (Sosa, 174). This is important to consider because these businesses export 90% of the goods they manufacture to the United States and under the NAFTA agreement these goods are practically free from tax and customs fees. It is this economic mechanism which has led to the development of a “bi-national business cluster” in the Otay plateau, and city governments on both sides of the border support the growth of this “Foreign Trade Zone” (Sosa, 176). Leonard 5 The opportunity of employment created by this “business cluster” has brought with it exponential population growth and urban development to the San Diego-Tijuana border region. Sosa writes that unlike development in San Diego which adheres to a master plan, “the Mexican approach to planning oftentimes gives the government the functions of a private developer, owning the land and developing without any adherence to greater regulation.” This type of planning also excludes community-level input (Sosa, 176 [Herzog 1990]); community disconnect coupled with lack of local ordinances leads to environmental neglect. Sosa believes that national environmental policies limit local participation in policy enforcement and open the door to “boundary-spanning” programs like the La Paz Agreement, Border 2012, and SEMARNAT (Sosa, 176). These programs are meant to pick up the slack between national policy and local enforcement, but the effects are not observable at the community level in Los Laureles Canyon. What is observable at the community level is an ecological tragedy; trash dumps can be viewed from every vantage-point in the canyon. Over one hundred uncontrolled open dump sites line the ridge-tops of this sub-basin. The trash is urban solid waste (USW), and as Buenrostro et al found in their study of Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico there is a lack of documentation on waste generation in developing countries (Buenrostro. 2001, 169-176). What has been documented, however, is lack of planning for solid waste management. In a later study of multiple municipalities, Buenrostro and Bocco cite that “in the ten largest cities of Mexico, where 70% of the population reside, waste disposal systems are inadequate” (Buenrostro. 2003, 251). This is certainly the case in Los Laureles where the city contracts with private disposal companies to collect trash once each week; the problem is that residents must be home and ready to pay cash at time of pick-up (Romo. 2010). Since the typical resident is away at work six days per week, this Leonard 6 is not a feasible system. When uncollected waste starts to accumulate, uncontrolled dumping is the only recourse for most residents. This is where the problem of trans-border trash flow begins. In a 2000 study conducted by Frisvold and Caswell, they note “ninety percent of the 12 million people who live within the US-Mexico border are clustered into 14 pairs of sister cities.” This population is subjected to inadequate water supply, limited treatment plants, and unregulated pollution (Frisvold and Caswell. 2000, 101). Frisvold and Caswell analyze these “post-NAFTA” issues in conjunction with the 1983 La Paz agreement, the creation of the BECC, the NADBank, and the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC); agencies commissioned to finance water, wastewater, and solid waste projects in the border region. One purpose of these institutions is to address market failures that are linked to environmental problems; “market failures that allow industrialization and population growth to proceed without thought to the social costs of [unplanned] growth.” Their biggest criticism is that the IBWC’s focus is on post-problem sanitation and not pro-active solutions; environmental problems are bargained rather than regulated (Frisvold and Caswell, 104). The results of “environmental bargaining” can be observed in the Los Laureles canyon in the form of unplanned growth, inadequate infrastructure, poor building standards, and lack of public services. Residents of our canyon of study are what Johnson and Niemeyer call “Victims of environmental industrialization” and can be compared to residents living atop a landfill near Derechos Humanos, Mexico (Johnson and Niemeyer. 2008, 371-382). Their study highlights the production of “waste associated with capitalism” and questions the “unequal distribution of environmental costs” that fly-in-the-face of global policies (Johnson and Niemeyer, 372). While the Los Laureles study in not framed by environmental justice, it is apparent in the canyon that residents are certainly victims of capitalism and injustices brought about through globalization. Leonard 7 Los Laureles has become highly urbanized over the past five years, and this rapid growth is a result of the expansion of the Mexican economy which is based on the growth of US-based factories or maquiladoras in the San Diego-Tijuana region. Johnson and Niemeyer postulate that the economic politics associated with “unregulated factories and unplanned communities” has created “a gap between the ecological problems border residents face and the large bureaucratic institutions established to address environmental issues” (Johnson and Niemeyer, 372). Our study of Los Laureles Canyon will bring non-governmental organizations, California agencies, San Diego City agencies, Mexico State and City Governmental agencies and Los Laureles community members together through educational outreach that will work toward closing that “gap.” Bringing these groups together is part of a larger binational approach to planning. This study will bring together a convergence of multiple binational agencies in an effort to thwart trans-border pollution of the natural environment. Directing the studies’ trash-tracking team is Oscar Romo; among many other organizations, Romo is a member of the Tijuana River Valley Recovery Team’s Binational Action Team. The Tijuana River Valley Recovery Team is: the place where local, state, and federal agencies on both sides of the border are coming together to define and implement a new strategy to resolve more than 70 years of degradation to the Tijuana River Valley. The premises of the Recovery Team are simple: If we can stop new trash and unwanted sediment before it reaches the valley, then we can successfully cleanup the valley. If we successfully cleanup the valley, then we can successfully restore its hydrology and natural values. If we can restore its hydrology and natural values, then we can successfully address the remaining water quality issues (TJ River Team Website). The Recovery Teams’ Mission is: To bring together the governmental administrative, regulatory, and funding agencies in tandem with advice from the scientific community, the environmental community, and affected stakeholders to protect the Tijuana River Valley from future accumulations of trash and sediment, identify, remove, recycle or dispose of To existing trash and Leonard 8 sediment, and restore the Tijuana River floodplain to a balanced wetland ecosystem (TJ River Team Website). The Binational Action Team’s goals are to: Identify Mexican and bi-national agencies and their responsibilities Identify existing and proposed binational agreements, efforts and funding sources in Mexico to address Tijuana River trash and sediment issues. Create value for Mexican government agencies working on the issues. Design a joint set of recommendations to stop the flow of trash and sediment at the source. Implement recommendations to abate trash and sediment at the source. Facilitate bi-national communications on Tijuana River recovery efforts (TJ River Team 2010) The Recovery Team’s missions and goals are important to note because they provide the framework for establishing research design methods used in the Los Laureles Canyon Study and will serve as a guideline for measuring the success of our research endeavors. Research Design/Methods Although previous studies have cited the problem of border-area solid-waste pollution, a lack of substantial published literature on the subject of trans-border waste management creates a need for case studies like Los Laureles Canyon. Lessons learned from this research can be used to create an international model for waste management in other trans-border watersheds. Controlling waste will also benefit international resource management along the U.S.- Mexico border; there are fourteen pairs of U.S.- Mexico border cities that all suffer the effects of solid waste pollution and trans-border flows. Finding a solution to providing local enforcement of environmental protection ordinances in Mexico is a win-win for all border communities. Leonard 9 Through direct observation in the field, this study will document uncontrolled open dumps and track trans-border waste-flows through the Los Laureles Canyon. The study will also include a literature review on the effects of economic globalization and urbanization in Mexico, and will provide critiques of Mexico’s environmental policies, Tijuana’s planning ordinances, and the San Bernardo Master Plan (a community located in Los Laureles Canyon). Case study research of the Los Laureles Canyon will be conducted under the direction of Oscar Romo, (NOAA Watershed Coordinator for the Tijuana River Watershed), as part of yearlong internship at the Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve (TRNERR). The study is designed to answer two fundamental questions: 1. Is the Los Laureles Canyon a source of waste that impacts San Diego County’s Estuarine Reserve (TRNERR) and neighboring beaches? 2. How does the global economy contribute to inconsistencies between national environmental policy and regional environmental planning? There are several reasons that this particular sub-basin of the Tijuana River Watershed was chosen for study: a. The geography and hydrology of the sub-basin; it drains directly into the estuary at the Tijuana National Estuarine Research Reserve (TRNERR) in Imperial Beach, California and impacts the entire Tijuana River Valley b. The number of open dump sites that surround the basin; at least 100 c. Lessons learned from the Los Laureles Case Study will be applicable to multiple canyon sub-basins in the Tijuana River Valley Leonard 10 d. The existence of strong international relationships established in this geographic area will aid researchers in accessing canyon dump sites There are two major goals for the Los Laureles Canyon Trash-Tracking Project and specific objectives/methods within each of the goals: Goal #1 – To Produce a Scientific Record of Uncontrolled Open Dump Sites in Los Laureles Canyon Objective #1 – Geo-locate and map all significant open dump sites using GPS and ArcGIS software Objective #2 – Record spatial attributes, land-use, and soil conditions of dump sites (in an effort to qualify conditions that stimulate waste flows) Objective #3 – Create database of sites attributes and geography including descriptive attributes of waste found at dump sites Goal #2 – Track the Flow of Trash from Los Laureles Canyon to TRNERR during Coastal Storms Objective #1 – Deploy 2,000 Trash-Tracker Probes housing RFID tags at significant dump sites in canyon (approx. 100 sites) Objective #2 – Map the course of trash-flows using ArcGIS software Objective #3 – Geo-locate Trash-Tracker Probes on the U.S. side of the border (post-storms) using RFID technology and map resting places Goal #3 – Share Scientific Record with Stakeholders: Community Members/Policy Makers/Government Officials Objective #1 – Provide database of baseline data Objective #2 – Provide map of canyon dump site locations Objective #3 – Provide map of trash-flow (initial site, progress, resting place) Objective #4 – Provide stakeholders with final analysis of case study Leonard 11 Anticipated Challenges of Research Goals: the ability to track trash depends heavily upon local weather patterns. If the area does not receive annually anticipated storms, we may not see any trash flow movement from canyon dump sites to estuary. In the event that winter rainfall is non-existent, (which is doubtful), this study will focus solely on the mapping and qualifying goals and will omit the tracking goal. Conclusion/Expected Outcome By combining background information on community master plans, regional plans, and national environmental policies with data collected in the field, this study will document uncontrolled open dumpsites and track the flow of waste through the Los Laureles Canyon of Tijuana, Mexico as it crosses the international border into San Diego County. The project will provide insight into the causes and sources of solid-waste pollution that threatens the protected habitats of the Tijuana River Estuarine Research Reserve and its surrounding beaches and ocean. Data collected will serve as a scientific record of the waste problem to be shared with both Mexico and U.S. officials. By project’s end, stakeholders will gain insight into international waste and resource management, as well as, cross-border environmental planning. Ultimately, this case will provide the foundation for legislative and regulatory policy change in Tijuana, and will result in a healthier watershed for the San Diego-Tijuana border region. Leonard 12 Los Laureles Canyon Trans-border Trash Tracking Budget RFID Tags: 2,100 Alien Short RFID Tag Avery Dennison AD-233 900MHz -Global Solutions .15 per tag (+ tax & freight) 365.00 2,500 Alien Short RFID Tag Avery Dennison AD-833 900MHz - Global Solutions .24 per tag (+ tax & freight) 675.00 Plastic Deployment Containers w/lids: 2,000 HDPE 1 gallon round Jugs Manufactured in Mexico (we pick up) Estimate .90 per container + tax 1,950.00 Handheld RFID tag Reader: Assembled by Javier Rodriquez 1,500.00 RFID Software: Developed by Javier Rodriquez 450.00 RFID Antenna: Alien 915 MHz Circular Antena (ALR-9611-CR) 40.00 Binoculars 400.00 Rain Gear 800.00 Plastic Tags 20.00 Portable Printer 900.00 Two-way Radios 200.00 GPS Devices 500.00 Digital Camera 200.00 Safety Gear 800.00 Aerial Imagery 3,500.00 Consulting Costs: Calit2 RFID Consulting $70.00 per hour/Javier Rodriquez 1,200.00 $25.00 per hour/Calit2 Interns Assistants: Data Collection/Field Work Data Entry Total Estimated Cost: 1,500.00 $15,000.00 Leonard 13 Bibliography Buenrostro, Otoniel, and Gerardo Bocco. 2003. Solid waste management in municipalities in Mexico: goals and perspectives. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 39, no. 3 (October): 251. doi:Article. Buenrostro, Otoniel, Gerardo Bocco, and Gerardo Bernache. 2001. Urban solid waste generation and disposal in Mexico: a case study. Waste Management and Research 19, no. 2 (April 1): 169 -176. doi:10.1177/0734242X0101900208. Frisvold, George B., and Margriet F. Caswell. 2000. Transboundary water management Gametheoretic lessons for projects on the US-Mexico border. Agricultural Economics 24, no. 1 (12): 101-111. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2000.tb00096.x. Good Neighbor Environmental Board. 2010. A Blueprint for Action on the U.S.-Mexico Border. http://www.epa.gov/ocem/gneb/gneb13threport/English-GNEB-13th-Report.pdf. Johnson, Melissa A., and Emily D. Niemeyer. 2008. Ambivalent Landscapes: Environmental Justice in the US-Mexico Borderlands. Human Ecology 36, no. 3 (June): 371-382. Peregrin, Chris. Conversations in 2010. Romo, Oscar. 2010. Conversations in 2010. Sosa, Oscar. 2008. Border Planning in the San Diego-Tijuana Region: Local Planning and National Policy. Berkeley Planning Journal 21: 170-183. Tijuana River Recovery Team. 2010. http://tjriverteam.org/Home_Page.html Wright, Richard D, Rafael Vela, Paul Ganster, San Diego State University, and Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico). 2005. Tijuana River Watershed Atlas = Atlas De La Cuenca Del Río Tijuana. San Diego, Calif: San Diego State University Press.