Relation of Offspring`s Psychiatric Diagnosis to the

advertisement

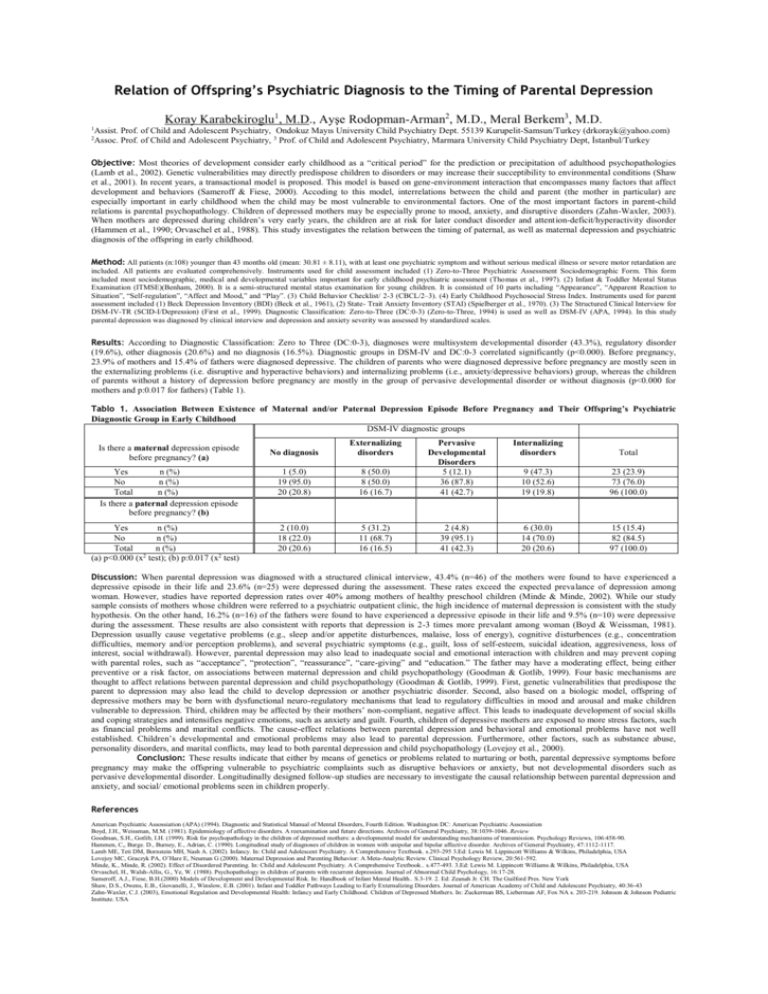

Relation of Offspring’s Psychiatric Diagnosis to the Timing of Parental Depression Koray Karabekiroglu1, M.D., Ayşe Rodopman-Arman2, M.D., Meral Berkem3, M.D. Assist. Prof. of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Ondokuz Mayıs University Child Psychiatry Dept. 55139 Kurupelit-Samsun/Turkey (drkorayk@yahoo.com) 2 Assoc. Prof. of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 3 Prof. of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Marmara University Child Psychiatry Dept, İstanbul/Turkey 1 Objective: Most theories of development consider early childhood as a “critical period” for the prediction or precipitation of adulthood psychopathologies (Lamb et al., 2002). Genetic vulnerabilities may directly predispose children to disorders or may increase their succeptibility to environmental conditions (Shaw et al., 2001). In recent years, a transactional model is proposed. This model is based on gene-environment interaction that encompasses many factors that affect development and behaviors (Sameroff & Fiese, 2000). Accoding to this model, interrelations between the child and parent (the mother in particular) are especially important in early childhood when the child may be most vulnerable to environmental factors. One of the most important factors in parent-child relations is parental psychopathology. Children of depressed mothers may be especially prone to mood, anxiety, and disruptive disorders (Zahn-Waxler, 2003). When mothers are depressed during children’s very early years, the children are at risk for later conduct disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Hammen et al., 1990; Orvaschel et al., 1988). This study investigates the relation between the timing of paternal, as well as maternal depression and psychiatric diagnosis of the offspring in early childhood. Method: All patients (n:108) younger than 43 months old (mean: 30.81 ± 8.11), with at least one psychiatric symptom and without serious medical illness or severe motor retardation are included. All patients are evaluated comprehensively. Instruments used for child assessment included (1) Zero-to-Three Psychiatric Assessment Sociodemographic Form. This form included most sociodemographic, medical and developmental variables important for early childhood psychiatric assessment (Thomas et al., 1997). (2) Infant & Toddler Mental Status Examination (ITMSE)(Benham, 2000). It is a semi-structured mental status examination for young children. It is consisted of 10 parts including “Appearance”, “Apparent Reaction to Situation”, “Self-regulation”, “Affect and Mood,” and “Play”. (3) Child Behavior Checklist/ 2-3 (CBCL/2–3). (4) Early Childhood Psychosocial Stress Index. Instruments used for parent assessment included (1) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1961), (2) State- Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Spielberger et al., 1970). (3) The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID-I/Depression) (First et al., 1999). Diagnostic Classification: Zero-to-Three (DC:0-3) (Zero-to-Three, 1994) is used as well as DSM-IV (APA, 1994). In this study parental depression was diagnosed by clinical interview and depression and anxiety severity was assessed by standardized scales. Results: According to Diagnostic Classification: Zero to Three (DC:0-3), diagnoses were multisystem developmental disorder (43.3%), regulatory disorder (19.6%), other diagnosis (20.6%) and no diagnosis (16.5%). Diagnostic groups in DSM-IV and DC:0-3 correlated significantly (p<0.000). Before pregnancy, 23.9% of mothers and 15.4% of fathers were diagnosed depressive. The children of parents who were diagnosed depressive before pregnancy are mostly seen in the externalizing problems (i.e. disruptive and hyperactive behaviors) and internalizing problems (i.e., anxiety/depressive behaviors) group, whereas the children of parents without a history of depression before pregnancy are mostly in the group of pervasive developmental disorder or without diagnosis (p<0.000 for mothers and p:0.017 for fathers) (Table 1). Tablo 1. Association Between Existence of Maternal and/or Paternal Depression Episode Before Pregnancy and Their Offspring’s Psychiatric Diagnostic Group in Early Childhood DSM-IV diagnostic groups No diagnosis Externalizing disorders Yes n (%) No n (%) Total n (%) Is there a paternal depression episode before pregnancy? (b) 1 (5.0) 19 (95.0) 20 (20.8) Yes n (%) No n (%) Total n (%) (a) p<0.000 (x2 test); (b) p:0.017 (x2 test) 2 (10.0) 18 (22.0) 20 (20.6) Is there a maternal depression episode before pregnancy? (a) Internalizing disorders Total 8 (50.0) 8 (50.0) 16 (16.7) Pervasive Developmental Disorders 5 (12.1) 36 (87.8) 41 (42.7) 9 (47.3) 10 (52.6) 19 (19.8) 23 (23.9) 73 (76.0) 96 (100.0) 5 (31.2) 11 (68.7) 16 (16.5) 2 (4.8) 39 (95.1) 41 (42.3) 6 (30.0) 14 (70.0) 20 (20.6) 15 (15.4) 82 (84.5) 97 (100.0) Discussion: When parental depression was diagnosed with a structured clinical interview, 43.4% (n=46) of the mothers were found to have experienced a depressive episode in their life and 23.6% (n=25) were depressed during the assessment. These rates exceed the expected prevalance of depression among woman. However, studies have reported depression rates over 40% among mothers of healthy preschool children (Minde & Minde, 2002). While our study sample consists of mothers whose children were referred to a psychiatric outpatient clinic, the high incidence of maternal depression is consistent with the study hypothesis. On the other hand, 16.2% (n=16) of the fathers were found to have experienced a depressive episode in their life and 9.5% (n=10) were depressive during the assessment. These results are also consistent with reports that depression is 2-3 times more prevalant among woman (Boyd & Weissman, 1981). Depression usually cause vegetative problems (e.g., sleep and/or appetite disturbences, malaise, loss of energy), cognitive disturbences (e.g., concentration difficulties, memory and/or perception problems), and several psychiatric symptoms (e.g., guilt, loss of self-esteem, suicidal ideation, aggresiveness, loss of interest, social withdrawal). However, parental depression may also lead to inadequate social and emotional interaction with children and may prevent coping with parental roles, such as “acceptance”, “protection”, “reassurance”, “care-giving” and “education.” The father may have a moderating effect, being either preventive or a risk factor, on associations between maternal depression and child psychopathology (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Four basic mechanisms are thought to affect relations between parental depression and child psychopathology (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). First, genetic vulnerabilities that predispose the parent to depression may also lead the child to develop depression or another psychiatric disorder. Second, also based on a biologic model, offspring of depressive mothers may be born with dysfunctional neuro-regulatory mechanisms that lead to regulatory difficulties in mood and arousal and make children vulnerable to depression. Third, children may be affected by their mothers’ non-compliant, negative affect. This leads to inadequate development of social skills and coping strategies and intensifies negative emotions, such as anxiety and guilt. Fourth, children of depressive mothers are exposed to more stress factors, such as financial problems and marital conflicts. The cause-effect relations between parental depression and behavioral and emotional problems have not well established. Children’s developmental and emotional problems may also lead to parental depression. Furthermore, other factors, such as substance abuse, personality disorders, and marital conflicts, may lead to both parental depression and child psychopathology (Lovejoy et al., 2000). Conclusion: These results indicate that either by means of genetics or problems related to nurturing or both, parental depressive symptoms before pregnancy may make the offspring vulnerable to psychiatric complaints such as disruptive behaviors or anxiety, but not developmental disorders such as pervasive developmental disorder. Longitudinally designed follow-up studies are necessary to investigate the causal relationship between parental depression and anxiety, and social/ emotional problems seen in children properly. References American Psychiatric Assossiation (APA) (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Assossiation Boyd, J.H., Weissman, M.M. (1981). Epidemiology of affective disorders. A reexamination and future directions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 38:1039-1046. Review Goodman, S.H., Gotlib, I.H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychology Reviews, 106:458-90. Hammen, C,, Burge. D., Burney, E., Adrian, C. (1990). Longitudinal study of diagnoses of children in women with unipolar and bipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 47:1112-1117. Lamb ME, Teti DM, Bornstein MH, Nash A. (2002). Infancy. In: Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. A Comprehensive Textbook. s.293-295 3.Ed: Lewis M. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G (2000). Maternal Depression and Parenting Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20:561-592. Minde, K., Minde, R. (2002). Effect of Disordered Parenting. In: Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. A Comprehensive Textbook.. s.477-493. 3.Ed: Lewis M. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, USA Orvaschel, H., Walsh-Allis, G., Ye, W. (1988). Psychopathology in children of parents with recurrent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 16:17-28. Sameroff, A.J., Fiese, B.H.(2000) Models of Development and Developmental Risk. In: Handbook of Infant Mental Health.. S.3-19. 2. Ed: Zeanah Jr. CH. The Guilford Pres. New York Shaw, D.S., Owens, E.B., Giovanelli, J., Winslow, E.B. (2001). Infant and Toddler Pathways Leading to Early Externalizing Disorders. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40:36-43 Zahn-Waxler, C.J. (2003), Emotional Regulation and Developmental Health: Infancy and Early Childhood. Children of Depressed Mothers. In: Zuckerman BS, Lieberman AF, Fox NA s. 203-219. Johnson & Johnson Pediatric Institute. USA