Summary of Hydro discussions - Library

advertisement

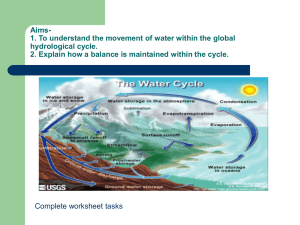

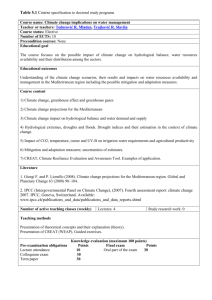

Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale Summary of Workshop Discussions Fazenda Rio Negro Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil 21-25 April 2006 1 Introduction While networks of conservation areas are the most effective tactic for preventing species extinctions in the near-term, the long-term persistence of both threatened species and sites also depends on the maintenance of critical ecological processes at a sea/ landscape-scale. Complex hydrological processes create the conditions for a range of habitats (e.g., floodplains, lakes, shorelines) that are of critical importance to threatened species. Hydrological processes also generate important socioeconomic benefits by supplying water for daily needs, agriculture, fisheries, hydroelectric energy and other industrial uses, and by contributing to flood defense and supporting harvestable biodiversity resources (e.g., fish, crabs). Disruptions to hydrological processes (e.g., due to unsustainable intervention from dam development, deforestation, or pollution) have been identified as significant threats to both biodiversity and sustainable economic development. Integrating hydrological processes into conservation planning at the landscape scale is a technical challenge that requires the close collaboration of both biodiversity conservation and hydrological expertise. Conservation International is therefore leading a collaborative learning initiative to bring together conservation partners and centers of freshwater expertise, including the African Wildlife Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, the Wildlife Conservation Society, the World Wildlife Fund, the IUCN Freshwater Program and Wetlands International. The initiative enables partners to share expertise and lessons learned on the integration of hydrological processes into conservation planning at the landscape scale to address key questions: How do changes in hydrological processes impact on globally threatened species and/ or KBAs and the ecosystem services they provide? How do we map and quantify hydrological processes and patterns and identify clear targets or thresholds for hydrological processes to ensure the persistence of globally threatened species, KBAs, and the ecosystem services they provide? How do we value the biodiversity and ecological benefits of functioning hydrological processes to the wider economy and society? How do we integrate hydrological information with biodiversity and socioeconomic data to support the design of effective conservation strategies at the landscape scale and how do we integrate these conservation strategies in sustainable development planning? As a first step in this collaborative initiative, CI-Brazil hosted a workshop at the Fazenda Rio Negro in the Pantanal, the world's largest contiguous wetland. This first workshop focused on the identification of targets for maintaining hydrological processes and key threats to those processes, drawing upon experiences gained through several case study analyses being conducted in the field and providing lessons for the other case studies about to embark on similar analyses. A second workshop will look at the process of defining threats and pressures on the system, engaging with the relevant stakeholders, identifying the types of conservation interventions that might be most effective given the local/ regional contexts, and identifying the types of analyses required to properly implement those interventions. The case study teams will then integrate the various layers of biodiversity, hydrological, threats and intervention analyses to develop a cohesive strategy for conservation. Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 1 Overview of Hydrological Processes and Wetlands [Insert summary of Ward’s presentation here? and link to presentation] Overview of Workshop Discussions In preparation for the workshop, we developed a framework presentation that outlines the different approaches to conservation planning of the main conservation organizations with particular reference to hydrological processes [insert link to Charlotte’s framework presentation and text]. In this summary report, we have synthesized and loosely grouped discussions during the course of the Pantanal workshop into three sets of issues that roughly correlate with the main stages in conservation planning outlined in the framework document: i. linking and mapping biodiversity targets to hydrological processes; ii. measuring and quantifying hydrological processes, and collecting and managing data; iii. understanding and analyzing threats, pressures and livelihood dependence on hydrological systems, and integrating of biodiversity and socio-economic concerns for conservation planning adnaction. A number of recurring discussion points are worth emphasizing here: The difference between restoration agendas in altered hydrological systems (e.g. Savannah, Chilika, Loktak) and more pre-emptive conservationist agendas in wilderness areas (e.g. Pantanal, North Rupununi, Milne Bay, Mamberamo). In some cases, both agendas are present within the same landscape. For example, the Pantanal wilderness largely has a conservationist agenda, but at smaller scales, such as the Cuiabá watershed, restoration may now be the priority. The distinction between focusing on specific biodiversity targets (e.g. species or sites) and aiming to restore a ‘natural flow regime’ for the benefit of entire communities or ecosystems. The balance between a focus on flow as the master variable (especially in altered systems) and water quality (especially in wilderness areas and for coastal biodiversity targets). TNC has focused on restoration of altered systems with hydrological flows as the master variable [insert link to David Harrison’s presentation], but acknowledges that restoring flows may not always be sufficient to restore ecological integrity. The underlying assumption is that closer approximation to “natural” flows will bring back biodiversity. However, in some cases, such as the Pantanal, current biodiversity concerns center on water quality issues [insert link to Debora Calheiros presentation]. Differences of scale in conservation planning for biodiversity (often macro-watersheds and/ or landscapes), analytical approaches (often defined by politico-administrative boundaries), and implementation (often at a micro-watershed or more local administrative scale). The contrast between the need to integrate freshwater, coastal and marine systems in conservation planning and constraints imposed by the institutional structure and divisions in policy and governing institutions. Recognition that this work necessarily requires multidisciplinary knowledge and an integrative approach – and thus requires a network of folks with the wide range of skills, but a common conservation vision, to achieve the broad goals. The case studies all have different starting points and agendas – and as such, there may be a need to identify a suite of different approaches/ methodologies that are relevant to the different contexts. Please see Annex I for the Workshop Agenda and Annex II for a List of Participants. Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 2 1. Mapping biodiversity targets to hydrological processes The challenges of mapping biodiversity targets to hydrological processes - a component often missing in terrestrial/ freshwater conservation planning - was a focal question for this workshop. For species targets, WCS demonstrated how basic ecological research on species distribution and habitat niches is a prerequisite for mapping biodiversity targets to hydrological processes. [insert link to WCS case study]. CI-Brazil outlined their analysis on species distribution and hydrological requirements in the Pantanal, and raised the question of the reliability of statistical analysis based on relatively few data points (e.g. 30-50 data points). [insert link to Pantanal case study – both George Camargo’s and Ricardo Machado’s presentations]. CSIRO demonstrated how well designed surveys can target data gaps [insert link to Chris Margules’ presentation]. The North Rupununi team is exploring methodologies for supplementing existing point locality data with inexpensive methods, such as monitoring by local communities. [insert link to North Rupununi case study]. TNC also showed how seasonal patterns and life-cycles of species can be linked to hydrological flows, by mapping critical stages to hydrographs. [insert link to David Harrison’s presentation] Wetlands International showed how species information may be linked to hydrological information by examining the relationship between biodiversity data and changes in water quality or quantity data through regression analysis. [insert link to Loktak Lake case study] IUCN’s Freshwater program identifies critical freshwater sites (at the scale of river basins or sub-basins) based on data on globally or regionally threatened and restricted range species (including fish, mollusks, odonates, crustaceans, plants). IUCN recognizes the need to take broader-scale hydrological processes into account, and aims to ensure the inclusion of representative hydrological, geological and topographical land forms within the selected sites [insert link to IUCN presentation]. CI follows a similar approach, as outlined in the Mamberamo presentation. [insert link]. TNC has focused on restoring ‘natural flow regimes’ for the benefit of entire communities or ecosystems rather than specific species or sites, and emphasizes the need to ensure adequate conditions for all species enough of the time rather than trying to create optimal conditions for all species all of the time. [insert links to both Karin Krchnak’s and David Harrison’s presentations]. This led to discussion about the relative importance of flow regimes and water quality, especially in systems where flow regimes have been less modified. For example, at the interface between freshwater and coastal systems, the salinity gradient plays a critical role in maintaining biodiversity (as in the Sundarbans and Chilika). [insert links]. Conservation planning in these brackish systems needs to build on an understanding of salinity gradients between low and high water seasons and the feedback relationships between freshwater and coastal systems. Similarly, in Milne Bay, changes in water quality attributed to erosion, sedimentation, pollution can have significant impact on the health and biodiversity of mangroves and coral reefs. [insert link] Questions were also raised about what is considered ‘natural’ given dynamic changes in hydrological processes and associated landscapes over time, as demonstrated by the natural variation in the Pantanal [insert link to Carlos Padovani’s presentation]. TNC uses the concept of sustainability boundaries – the boundary between acceptable and unacceptable changes in ecosystem health. This led to discussion about the different challenges of analyzing and predicting the cumulative impacts of changes in hydrological processes (e.g. construction of numerous small canals to divert water for village needs) versus catastrophic changes (e.g. construction of a large dam): How do we monitor the cumulative impacts – “death by a thousand cuts” – and what do we know about the tipping point for diversity between reversible and irreversible changes to the hydrological system? It was suggested that North Rupununi would be a good case study for addressing cumulative effects. North Rupununi is a wilderness area with a range of both small and large-scale threats looming, has a good monitoring system in place, and is of a “manageable” scale. Hydrographic characteristics can be used to identify threshold indicators and tipping points. [insert link to N Rupununi case study] Finally, there was some discussion about using species that directly depend on the hydro-ecosystem functions as indicators, for example, species that depend on freshwater food chains. (A proxy to measuring hydro-ecosystem function is the carbon content in streams and its impact on aquatic food Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 3 chains.) Another suggestion was to use the relatively abundant data on more common species as a means to understand species needs and to correlate these with hydrological processes. 2. Measurement and quantification of hydrological attributes Hydrological data are usually available in various shapes and forms, and for different objectives (e.g. for irrigation/ agriculture planning as with EMBRAPA in the Pantanal, and river flow/ dam management as in Chilika Lake) [insert links to case studies] The first challenge lies in identifying the key hydrological variables that are relevant for biodiversity targets (see discussion above on Mapping biodiversity targets to hydrological processes), and then obtaining and interpreting relevant data. Historical flow data are commonly used as the threshold or baseline in modeling and scenario-building exercises (as is applied in the Chilika Lagoon, Loktak Lake and Savannah case studies) [insert links to case studies]. However, it can be difficult to obtain consistent time-series stream/river flow information as these are usually held by government institutions and private industry interests. (TNC’s success towards restoring environmental flows in Savannah, Georgia is in large part due to their pivotal partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and access to flow data dating back to the 1880s. Having the right partner is critical!) Experiences from the group provided useful insights for addressing challenges of data (un)availability: i. WWF is currently developing a global hydrological database called HydroSHEDS, which will enable scientists to create digital river and watershed maps at multiple scales for conservation planning (http://www.worldwildlife.org/freshwater/hydrosheds.cfm). ii. Remote sensing data and GIS models provide relatively dependable data on the geophysical aspects of the landscape, as demonstrated for the Pantanal. [insert link to Carlos Padovani’s presentation] iii. For primary data collection activities, understanding the critical data gaps (building on a preliminary assessment of the relationship between biodiversity targets and hydrological processes) will facilitate appropriate survey designs that target scientific gaps in an efficient and effective manner within the large landscapes. This will also lend a stronger and more robust basis when extrapolating the data in analytical procedures. iv. There are important technical issues related to interpolation from scarce data points – the choice of which analytical approach to use (e.g. statistical regressions, spatial modeling, economic simulations) will define the nature and validity of results and should be considered carefully. v. Integrating local knowledge into the process. The North Rupununi Wetlands project has put in place a data collection and monitoring program with the local communities around the wetlands and has 2+ years worth of data waiting to be analyzed. The project is also in the process of developing a software program called Ecocensus (with Open University, UK) that integrates information gathered from participatory processes with a GIS interface, with the objective of using the data to facilitate adaptive management. This approach has also raised additional questions with regards to the process of engagement with local communities/ stakeholders, issues of ownership and how to address capacity building needs. [insert link to North Rupununi case study] vi. In regions where data is scarce, the USFS/ AWF’s rapid assessment exercise in the Zambezi provided clues on what might be considered important basic data layers. These include: characteristics that impact physical water flow and storage regimes (terrain, geology, soils, climatic cycles) vegetation cover land surfaces such as roads institutional information, such as dam management and planning Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 4 We did not deal explicitly with issues surrounding data collection and management, and this was raised as an important component of the analytical process as data format/ structures will influence the scope for analysis. 3. Threats, pressures, stakeholders – and conservation planning that integrates biodiversity and socio-economic concerns While the topics of identifying threats and pressures, engaging stakeholders and determining analyses to support conservation interventions are to be addressed in greater depth during the next workshop, the discussion was started here with recognition that a proper understanding of the local context (socioeconomic, demographic, policy, development, culture) is critically important for identifying points in the landscape in time/space that provide opportunity for action. There is also recognition that it is extremely difficult to examine biodiversity targets in isolation from regional development and local livelihood needs. Local stakeholders should be involved in the planning process from the start as there may be inherent synergies between biodiversity, hydrological processes and community needs that should be capitalized upon for conservation planning (as was wonderfully illustrated in the Chilika case study). Often, local communities use resources in a sustainable manner and are dependent on ecological services to maintain livelihoods – this can offset the costs of other threats, but more often not. Where there is not this synergistic relationship and/or if the costs of other pressures are too high, the question then moves to how we can create incentive systems to compensate for changed behavior at both local use and regional policy levels. How do we measure and quantify the trade-offs at the different scales? It is recognized that trade-offs are not of equal measure (even though in same currency) especially in regions with very low incomes. The use of local knowledge to fill scientific gaps is another important consideration for early engagement. For example, fishermen in India usually look to river dolphins as a signal of healthy fish stocks and older fishermen in the Pantanal have contributed much information to EMRAPA’s water quality study. There was also some discussion on different approaches to engaging and communicating with stakeholders. The latter is particularly important as the integrated models and analyses often produce very sophisticated information that requires a certain skill in translating into a language easily understood by local communities and policy-makers. As such, it is important to understand the local needs/ priorities a priori to any analysis or scenario-building exercise. Additionally, the engagement process is important for building a commonly agreed vision and to enable adaptable management as events (whether geophysical or political) are dynamic and often unexpected. In particular, bringing local/ regional institutions early into the process builds capacity for decision-making, and is recognized as a potential mechanism to ensuring continuity beyond the funding cycle of NGOs. In terms of threats and pressures on hydrological systems, those most often discussed/ addressed in the case studies include: dams and other management structures (for water diversion, flood mitigation, etc.), land use and land cover change (and its associated impacts of sedimentation, pollution, etc.), and climate change. The following questions were then raised: What is the analytical process? How do we prioritize threats? How do we integrate the threats and socio-economic information with the biodiversity and hydrological targets? The ability to project future land use/ cover change and its impacts on hydrological patterns, and biodiversity, is critical to a proactive approach in dealing with pressures. It is argued that this forward looking component be an integrative part of the conservation planning process, as opposed to being tacked-on in an ad hoc manner, in order to enable planning for adaptability and resiliency over the longterm. Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 5 Similarly, building projections and scenarios of changes in flows and linking their impacts to both biodiversity and livelihoods is very important to finding conservation solutions that do not make local stakeholders worse off. In addition, the ability to translate those impacts into economic terms is a powerful tool for influencing policy and management. Economics is often the common language for speaking with government. The use of economic valuation is useful as a policy tool in opening the door to discussions with decision-makers for determining trade-offs between environmental and social capital. Aside from valuation, an economic approach is also useful to finding possible alternatives in meeting conservation and development needs in extreme cases, for example, drought and food insecurity. On the other hand, the usefulness of economic valuation of water and hydrological cycles are not clear for wilderness areas where trade-offs (and competing land/ resource uses) are not as prevalent or present as in fragmented systems. How then does one communicate or “sell” broad-scale conservation to policy-makers? What are the various types of conservation incentives for hydrological systems? However, caution was raised – and rightfully so – with regards to the current dependence on markets for solutions to conservation issues. Market solutions are typically very socially and environmentally insensitive in many contexts, and have very limited or discrete applicability. A suggestion was put forth for a compilation of case studies on the environmental and ecological costs – including the corresponding distributional and equity issues – of dam construction from different regions in the world. These costs can potentially be developed into an “index” for adjusting the standard cost-benefit analyses of dam construction to its real costs. This work is currently proposed under the Millenium Development Goals. Conservation actions should capitalize on policy structures that already exist, such as National Water Management Plans, Environmental Impact Statements for dam construction, etc. Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 6 Follow-up activities to the Workshop: Various tools and products that were identified as useful (in no particular order of importance/ priority): i. Guidance for managing data – databases for organizing/ storing data from multiple sources, and for making it available to share with others. EMBRAPA has some experience with this. ii. Training course – adaptation of Wetlands International’s course for wetland managers? iii. “Idiot’s Guide to Hydrology” – two objectives were put forth for such a document: 1) to inform and communicate the value of hydrological systems to stakeholders/ policymakers, and 2) nuts and bolts of how to do basic hydrological research and monitoring techniques for ecological/ conservation objectives iv. Document case studies of both successes and bad projects (for examples of how NOT to do something) v. Identify various tools/ software on modeling hydro-ecological processes, and integrative models that address biodiversity and socio-economic objectives spatially vi. Economic valuation techniques for hydrological processes vii. Develop collaborative demonstration sites/ projects viii. Share the software/ manuals developed by the North Rupununi project on integrating traditional knowledge into conservation planning and monitoring ix. Use of “cartoons” for illustrating the hydro-biodiversity-socioeconomic linkages and for communication – see for example those developed by TNC x. Development of a Hydrology Award – given annually to “best” project/ person/ analysis on biodiversity-hydrology. Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 7 Annex I: Working Agenda April 21st 9.00-9.15 Welcome (CI-Pantanal) 9.15-10.00 Overall framework – overview of how the different approaches of the partner organizations fit together and the focal steps for this workshop. (CI-DC) 10.00-11.00 Overview of the science - review of the linkages between threatened species, sites, systems and hydrological processes. (Wetlands International and IUCN Freshwater Programme) 11.30-1.30 A framework for setting targets for hydrological processes, assessing human dimensions, and identifying actions: - TNC’s Ecologically Sustainable Water Management framework applied to Savanna (GA) case study. (TNC) - Identifying issues, developing flow scenarios and securing benefits for nature and people for Chilika Lagoon in India. (Wetlands International) 2.30-4.30 Pantanal case study presentation – each case study team provides of an overview of: introduction to region the conservation planning process so far, species, sites and other focal biodiversity targets, and their dependence on hydrological flows, key attributes of hydrological flows (e.g. wet and dry season base flows, normal high flows, extreme drought and flood conditions, rates of flood rise and fall, internannual variability in these attributes etc.) – including information already available on the current and desirable/ natural status of key attributes, additional data available to define these key attributes, critical data gaps; main threats to hydrological processes and hence biodiversity; brief outline of human development objectives that are threatened by changes in hydrological processes. After each case study presentation, there will be detailed discussion of the key attributes of hydrological flows, methods for defining current and desirable/ natural status of these attributes, and ways to deal with data constraints. April 22nd 9.00-11.00 Zambezi Case Study – as per Pantanal case study 11.30-1.30 Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna Case Study – as per Pantanal case study 2.30-3.30 Milne Bay Mini Case Study* 3.30-4.30 Mamberamo Mini Case Study* 4.45-5.45 North Rupununi Wetlands Case Study *These programs are at fairly early stages of planning for integrating hydrological processes, so case study presentations will be shorter and discussion will focus on broader strategic directions rather than detailed data and analysis needs. Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 8 April 23rd Field Trip April 24th Case study clinics: Each case study team will have a time-slot allocated in which they can ask invited experts to provide input and guidance on their planning process for setting targets for hydrological processes. Feedback on next steps for setting targets for hydrological processes – each case study team will provide a brief summary of what they have learned through the workshop and any new plans for moving forward. General summary of what we have learnt at this workshop and identification of any additional learning questions for the rest of this phase. Discussion of the types of tools, guidance materials and other resources/ approaches that would support ongoing lesson-learning (bearing in mind, resources etc. that already exist.) April 25th Tackling issues of identifying threats, engaging stakeholders and conducting analyses to integrate biodiversity, hydrology and socio-economic information for defining a conservation strategy 9.00-10.15 Incorporating biodiversity/hydrology targets into resource use planning at the management and policy levels (CSIRO) 10.15-11.00 Process of engagement, communication and planning for conservation action in North Sumatra (CI) 11.15-12.00 Use of economics in conservation planning for Loktak Lake, India (Wetlands Intl) Accounting for, and negotiation of, the varied institutional and economic demands on hydrological resources for the development of management plans Discussion on the range of analyses, methods and approaches for integrating socio-economic demands and biodiversity information in large hydrological systems. Planning for the next workshop (All) Discussion on action plans with the individual case study teams (Pantanal, Milne Bay, Mamberamo, Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna, North Rupununi) Discussion with GCP partners on workplans and budgets for next workshop (CI, TNC, WWF, WCS, Ward, IUCN) Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 9 Annex II: Participant List Name Institution Curtis Bernard Charlotte Boyd Craig Busskohl Débora Calheiros George Camargo Ward Hagemeijer David Harrison Nev Kemp Karin Krchnak Ritesh Kumar Ricardo Machado Chris Margules Anna McIvor David Mitchell Henny Ohee Carlos Padovani Indranee Roopsind Nikolai Sindorf Brian Smith Chaman Trisal Grace Wong Conservation InternationaI-Guyanas Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International US Forest Service EMBRAPA-Pantanal Conservation International-Brazil Wetlands International The Nature Conservancy Conservation International-Indonesia The Nature Conservancy Wetlands International Conservation International-Brazil CSIRO IUCN Freshwater Programme Conservation International-Melanesia Conservation International-Indonesia EMBRAPA-Pantanal Iwokrama World Wildlife Fund Wildlife Conservation Society Wetlands International Conservation International Integrating Hydrological Processes into Conservation Planning at a Landscape Scale 10 [Insert logos of all participating organizations here.]