Letter to Conference Committee

advertisement

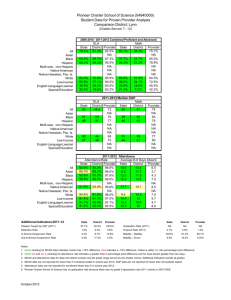

January 12, 2010 Re: Education Reform Act of 2009 Honorable Conference Committee Members: I am writing about the “Education Reform Act of 2009,” its versions currently being reconciled by your committee. Since Boston, and perhaps other districts, want this legislation, it seems to me this bill should be limited in application to Boston and such other districts as vote to accept it. Indeed, I myself would vote for this bill under those conditions. As it is, this bill hurts my district, principally by raising the cap on charter school sending tuition, based on Somerville’s standing in the lowest 10% of MCAS scores. To recapitulate remarks I made during the House debate on Wednesday, Somerville’s MCAS scores are indicative of a student population in which poor children, those with special needs, and English language learners, are disproportionately present. To compound the challenges of this population, it is a highly mobile one, with close to 20% turnover per year, with the result that the MCAS tests are not being administered to the same students from year to year, but to significant numbers of students who have been educated elsewhere (see attached note)*. Of the 366 Somerville students who finished the Fiscal Year 2009 school year in charter schools, all but 4 attended Prospect Hill Academy (PHA), a 950-student charter school whose MCAS scores are quite similar to Somerville’s MCAS scores. Prospect Hill Academy itself is in Improvement Year 1, for subgroups, for English Language Arts (ELA), under No Child Left Behind (NCLB), data which is available on the DOE website. Admittedly, the Somerville Schools are in are in Corrective Action for both ELA and math under NCLB. Yet I would also note that, under NCLB AYP data for 2009, PSA met its subgroup performance targets for no subgroups except “white” children, in ELA or in mathematics. Yet, compare the subgroup populations for the Somerville Public Schools and Prospect Hill Academy (PHA): Interestingly, the DOE website does not list schools or districts as ranked by MCAS results, although one hears of “failing” charter schools in Lowell, Boston, and elsewhere. Criterion Somerville PHA Below Poverty Line English Not Home Language Limited English Proficiency Receive SPED Services 68% (12th in state) 50.5% (4th in state) 16.8% (8th in state) 22.7% (7th in state) 54.5% 42.4% 1.7% 6.6% Since we are concerned with “achievement gaps,” perhaps we should be comparing how the Somerville Schools do relative to PHA. Not only is PHA working with much lower percentages of the most challenging subgroups, it operates under a regulatory system that gives it competitive advantage. Unlike the public schools, PHA can screen out or demote lower-performing students through its “placement test” system, set a maximum class-size, and refuse to accept new students once the school year has begun. The fiscal impact on the City of Somerville of having this advantaged competitor is enormous. From its 2009 school budget of $47.9 million ($72.6 million net school spending), $5.1 million was marked for charter school sending tuition, reduced at the end of the year to $4.65 million, in consideration of the 20 students who left the charter school during the year. This cash transfer means that 22% of Somerville’s chapter 70 aid for 2009 followed 8.2% of its students, into charter schools. Even under existing law, Somerville’s charter school sending tuition could rise to $6.65 million under its present cap; under the bill before us, the cap (based on 2009 net school spending) could rise to $13.3 million. The impact of such cuts can only be crippling to a district struggling with high school student mobility as it educates challenging subgroups. Such a transfer is unjustified, and ultimately punitive. It could be ameliorated by certain modifications to the bill, which I urge upon you: 1) Both the definition of an “underperforming” school, and of conditions that would trigger a charter cap increase, should be based on a more nuanced metric that includes student growth data and mobility as performance factors. 2) School evaluation should take place with reference to objective, reasonable performance criteria. We should not legislate punishment for any district for being simply in the lower 10 or 15 percent of curve-graded scores, if its score is above an acceptable minimum rating. 3) To protect districts from sudden increases in charter tuition, increases in the cap from 9 to 18% should be in maximum .5% increments annually. Such a change would also result in less displacement for charter students in cases where district MCAS scores rise out of the bottom 10%. 4) The Senate version addressed the issue of over-prediction of student enrollment by basing tuition on the previous year’s enrollment. As can be seen in the 2009 example from Somerville, such over-prediction can result in significant school funds being withheld from public school until year-end reckoning. 5) The Senate version of backfilling is preferable. It’s unfair to districts to have to take students back at any point before graduation, and to accept new students from out of district or even other countries, as by law they must, while allowing charters to refuse entrance to new students after the first year or two. 6) IEP teams at charter should be required to have district representation if they’re recommending out-of-district placement, as in the Senate version. The district SPED personnel know the resources available in and out of district far better. And the district will have to pay for the placement. As Superintendent Roy Belson of Medford argues “[i]f a charter school determines that a SPED student may require an outside placement which will financially obligate the local district, then the team meetings should be conducted by the local district with input from the charter.” 7) Districts should not be required to give leave to teachers with professional status. 8) Teachers should not be subjected to arbitrary judgments and actions. The inherent assumption that low MCAS scores are attributable to poor teacher performance is unfair, and will serve to discourage teachers from serving in the most disadvantaged schools. 9) At least a quorum of members of the BESE should attend any hearing on a charter school application. Any lesser requirement is disrespectful to communities and to the principle of deliberative process. 10) We should institute real consequences for Commonwealth charter schools whose performance is comparable to the lowest-performing district schools, and generally even the playing field between public schools and charters. As one final note, I would like to comment on the often-repeated statement that it is imperative to pass this bill in order to win “Race to the Top (RTTT)” dollars for Massachusetts. The only evident overlap between the Education Reform Act of 2009 and the state’s RTTT application would seem to be in the area of underperforming schools. Yet our existing statute, MGL Chapter 69, SS IJ, as amended by 2008, 311, Section 5, contains most of the dire remedies contained in this bill, including giving superintendents power to replace principals, who, in turn, may dismiss teachers without regard to any collective bargaining agreement. Since we amended the statue to be effective August 14, 2008, the schools designated underperforming pursuant to it will not yet have had the 24 months after approval of their remedial plans, either to show improvement, or not. Why are we repealing this statute now, when we cannot properly judge it to have succeeded or failed? As for the RTTT application as a whole, my comments on it to Mass DOE may be found attached. Thank you for your consideration of these comments. Respectfully submitted, Denise Provost cc: Senator Patricia Jehlen Representative Timothy J. Toomey Representative Carl Sciortino Joseph Curtatone, Mayor of the City of Somerville Somerville School Committee Members Anthony Pierantozzi, Superintendent, Somerville Public Schools *Note on Student Mobility DESE recognizes that student mobility is an important factor in evaluating how schools really perform. It is currently trying to devise a system for rating mobility. It aims to take into account 3 resources of mobility: intra-district mobility, inter-district mobility, and “churn” – the letter being sheer numbers of students leaving and coming in. To get a sense of the impact of mobility, consider that Massachusetts’ 24 urban public school districts have an average mobility rate of 15.6% a year, ranging from a low of 9.6% (Pittsfield and Leominster), to a rate of 26.2% in Holyoke. By contract, the non-urban districts have an average mobility rate of 5.8%, with a low of 1.5% in Duxbury, to a high of 15.2% in Randolph and Greenfield. Somerville ranks above the urban district average for mobility at 17.8% in 2009, down from 25% in 2005. For a gauge of the impact of student mobility on student performance, we can look at two sets of 10th grade scores on the 2006 Math MCAS test. For the “stable” cohort – those registered in Somerville High School from the beginning of their freshman year – the average score was 91.2; for those not so registered – the “non-stable” cohort – it was 64.8. The 16.4 point difference represents almost a full index criterion between groups in Somerville; the spread between the respective groups in Chelsea was 21.2.