M&Mrevised - Critical Research on Men in Europe

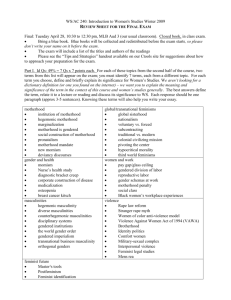

advertisement