Annotated Bibliography

advertisement

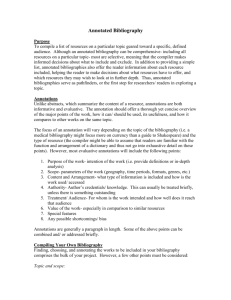

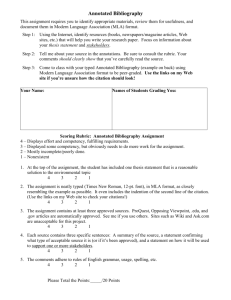

J. Dym Annotated Bibliography WHAT IS AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY? An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, and documents. Each citation is followed by a brief (usually about 150 words) descriptive and evaluative paragraph, the annotation. The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited. ANNOTATIONS VS. ABSTRACTS Abstracts are the purely descriptive summaries often found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles or in periodical indexes. Annotations are descriptive and critical; they expose the author's point of view, clarity and appropriateness of expression, and authority. THE PROCESS Creating an annotated bibliography calls for the application of a variety of intellectual skills: concise exposition, succinct analysis, and informed library research. First, locate and record citations to books, periodicals, and documents that may contain useful information and ideas on your topic. Briefly examine and review the actual items. Then choose those works that provide a variety of perspectives on your topic. Cite the book, article, or document using the appropriate style. Write a concise annotation that summarizes the central theme and scope of the book or article. Include one or more sentences that (a) evaluate the authority or background of the author, (b) comment on the intended audience, (c) compare or contrast this work with another you have cited, or (d) explain how this work illuminates your bibliography topic. When writing, think about your source’s: purpose -- what is the source trying to do? form -- is it a book or an article or a....? arrangement -- how is the source organized? audience -- who is the source aimed at? authority -- is the author/publisher reliable? currency -- is the source up-to-date? coverage -- is the source comprehensive? ease of use -- are there any special features? J. Dym Annotated Bibliography What goes into the content of the annotations? Of course there are many different ways to write the annotations. Did you think there would be one simple answer? Not with writing! But we can categorize the most common forms of annotated bibliographies for you: Informative (summary--tell us what the main findings or arguments are in the source) Evaluative (tell us what you think of the source) Indicative (description--tell us what is included in the source) Combination (tell us all sorts of stuff!) Informative (summary--tell us what the main findings or arguments are in the source) Simply put, this form of annotation is a summary of the source. To write it, begin by writing the thesis; then develop it with the argument or hypothesis, list the proofs, and state the conclusion. Voeltz, L.M. (1980). Children's attitudes toward handicapped peers. American Journal of Mental Deficiency, 84, 455-464. As services for severely handicapped children become increasingly available within neighborhood public schools, children's attitudes toward handicapped peers in integrated settings warrant attention. Factor analysis of attitude survey responses of 2,392 children revealed four factors underlying attitudes toward handicapped peers: social-contact willingness, deviance consequation, and two actual contact dimensions. Upper elementary-age children, girls, and children in schools with most contact with severely handicapped peers expressed the most accepting attitudes. Results of this study suggest the modifiability of children's attitudes and the need to develop interventions to facilitate social acceptance of individual differences in integrated school settings. (Sternlicht and Windholz, 1984, p. 79) Indicative (descriptive--tell us what is included in the source) This form of annotation defines the scope of the source, lists the significant topics included, and tells what the source is about. This is different from the informative entry in that the informative entry gives actual information about its source. In the indicative entry there is no attempt to give actual data such as hypotheses, proofs, etc. Generally, only topics or chapter titles are included. Griffin, C. Williams, ed. (1982). Teaching writing in all disciplines. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Ten essays on writing-across-the-curriculum programs, teaching writing in discplines other than English, and teaching techniques for using writing as learning. Essays include Toby Fulwiler, "Writing: An Act of Cognition"; Barbara King, "Using Writing in the Mathematics Class: Theory and Pratice"; Dean Drenk, "Teaching Finance Through Writing"; Elaine P. Mairnon, "Writing Across the Curriculum: Past, Present, and Future". (Bizzell and Herzberg, 1991, p. 47) J. Dym Annotated Bibliography Evaluative (tell us what you think of the source) In this form of annotation you need to assess the source's strengths and weaknesses. You get to say why the source is interesting or helpful to you, or why it is not. In doing this you should list what kind of and how much information is given; in short, evaluate the source's usefulness. Gurko, Leo. (1968). Ernest Hemingway and the pursuit of heroism. New York: Crowell. This book is part of a series called "Twentieth Century American Writers": a brief introduction to the man and his work. After fifty pages of straight biography, Gurko discussed Hemingway's writing, novel by novel. There's a index and a short bibliography, but no notes. The biographical part is clear and easy to read, but it sounds too much like a summary. (Spatt, 1991, p. 322) Hingley, Ronald. (1950). Chekhov: A biographical and critical study. London: George Allen & Unwin. A very good biography. A unique feature of this book is the appendix, which has a chronological listing of all English translations of Chekhov's short stories. (Spatt, 1991, p. 411) Combination (tell us all sorts of stuff!) This is your catch-all category! Most annotated bibliographies are of this type. They contain one or two sentences summarizing or describing content and one or two sentences providing an evaluation. Easy as pie! Morris, Joyce M. (1959). Reading in the primary school: An investigation into standards of reading and their association with primary school characteristics. London: Newnes, for National Foundation for Educational Research. Report of a large-scale investigation into English children's reading standards, and their relation to conditions such as size of classes, types of organisation and methods of teaching. Based on enquiries in sixty schools in Kent and covering 8,000 children learning to read English as their mother tongue. Nable for thoroughness of research techniques. (Center for Information, 1968, p. 146) Annotated Bibliography: Examples: Graybosch, Anthony, Gregory M. Scott and Stephen Garrison. The Philosophy Student Writer's Manual. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. Designed to serve as either as a writing guide or as a primary textbook for teaching philosophy through writing, the Manual is an excellent resource for students new to philosophy. Like other books in this area, the Manual contains sections on grammar, writing strategies, introductory informal logic and the different types of writing encountered in various areas of philosophy. Of particular note, however, is the section on conductng research in philosophy. The research strategies and sources of information described there are very much up-to-date, including not only directories and periodical indexes, but also research institutes, interest groups and Internet resources. J. Dym Annotated Bibliography Martinich, A. P. Philosophical Writing: An Introduction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1989. An excellent introduction to the peculiarities of philosophical writing, ranging in difficulty from elementary to moderately advanced. Martinich maintains that half of good philosophy is good grammar and the other half is good thinking and his book is geared toward helping students to write clear, precise and concise philsophical prose. The book includes a crash course on basic concepts in logic, a catalogue of the types of arguments typically found in philosophical writing, and an examination of the structure of a philosophcial essay. Of particular interest is Martinich's discussion of the concepts of author and audience as they apply to academic writing. Rosenberg, Jay F. The Practice of Philosophy: A Handbook for Beginners, 2nd Edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1984. Intended as a general-purpose introduction to the practice of philosophy in the "analytic" style, Rosenberg's book includes quite a lot on philosophical writing. In effect, Rosenberg divides the class of philosophical essays into four main types: critical, adjudicatory, problemsolving and essays expositing an original thesis. A variety of critical and argumentative strategies are provided in connection with the first three types. Seech, Zachary. Writing Philosophy Papers. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 1993. As its title suggests, Seech's book deals specifically with writing philosophy papers. Included are sections on the five kinds of essays most often assigned in philosophy classes, as well as sections on writing strategies, grammar, research and documentation. The section devoted to reference resources in philosophy may be especially useful to undergraduates in middle-year courses who are looking for background information beyond that provided in assigned texts, but who need not yet be concerned with advanced research. Useful Reference Page http://leo.stcloudstate.edu/acadwrite/annotated.html Explanation; citation guides. SOURCES: Cornell University, Library References Division, http://www.library.cornell.edu/okuref/research/skill28.htm#what University of Wisconsin Writer’s Handbook, http://www.wisc.edu/writing/Handbook/AnnotatedBibliography.html Andrew Truxal Library, Arundel Community College, http://www.aacc.cc.md.us/library/annobib.htm Will Buschert, Philosophical Writing, An Annotated Bibliolgraphy: http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/philosophy/phlwrite/phlbib.html

![ENC 1102 Hybrid Day 24‹Parts of an Annotated Bibliography [M 4-9]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006813293_1-f9df0b3a4fca2bb83cd912cb9db27c26-300x300.png)