CLINICAL USE

Clin. Drug Invest. 11 (5): 251-260. 1996

1173-2563/96/0005-0251/$05.00/0

© Adis International Limited. All rights reserved.

Piracetam in Patients with

Chronic Vertigo

Results of a Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study

U. Rosenhall,1 W. Deberdt,2 U. Friberg,3 A. Kerr4 and W.Oosterveld5

1

2

3

4

5

Audiology Department, Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden

International Development, UCB Pharma, Braine-l'Alleud, Belgium

ENT Department, University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden

Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast, Northern Ireland

ENT Department, University Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Summary

The nootropic agent piracetam, which exerts diverse effects through actions

on cerebral neurotransmission, has been reported to alleviate vertigo. We performed a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and tolerability of piracetam 800mg 3 times daily orally for 8 weeks. The

study group consisted of 143 middle-aged and elderly outpatients of ear, nose and

throat clinics who had suffered from vertigo for at least 3 months, had experienced

at least 3 episodes per month, and the vertigo was severe enough to disrupt daily

life. Primary outcome measures were patient self-evaluations of vertigo: the

frequency of episodes, and their severity using visual analogue scales (VAS).

Malaise and imbalance between episodes (VAS), the effect of vertigo on walking

(VAS), the duration of incapacity, and overall evaluations by patients and investigators were also assessed. On entry, episodes were more frequent (p < 0.05) and

malaise between episodes more severe (p < 0.05) in the piracetam group. Data

were not evaluable in 54 patients because of either adverse events (12 piracetam,

12 placebo) or protocol deviations. An intention-to-treat analysis showed that

episodes of vertigo were less frequent (p < 0.03) but not less severe on piracetam

than on placebo: interval malaise (p < 0.05) and imbalance (p < 0.01) improved

more and the duration of incapacity was less (p < 0.05). These changes, which

were maximal after 8 weeks' medication, had almost disappeared 4 weeks after

the end of treatment. Tolerance to piracetam was good, with few drug-related

adverse events occurring. These findings provide further evidence that piracetam

alleviates vertigo by reducing the frequency of episodes, the severity of malaise

and imbalance between episodes, and the duration of associated incapacity.

Effective symptomatic treatment of chronic

vertigo remains a difficult therapeutic challenge.

Relief of symptoms is a particular problem in the

elderly, in whom vertigo, dizziness and

imbalance

constitute an important clinical and socioeconomic

problem. [1] The pathophysiology of vertigo and

the ability to compensate in the presence of this

disorder are dependent on central nervous system

function. With increasing age, central compensation after, for example, unilateral vestibular neuronitis may be slow and sometimes incomplete.

We describe a study with piracetam, a drug that

has been reported to relieve vertigo of both central

and peripheral origin. Piracetam is a nootropic

Rosenhall etd.

252

agent that improves higher cerebral integrative

functions and, at the same time, is without sedative

or psychostimulant properties.121 Its effects are

largely explained by its ability to facilitate central

neurotransmission. In particular, it is thought to

act by restoring both the number and function

of cholinergic (muscarinic) and excitatory amine

(N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptors in aged rats and

rnice[3-5] and the release of dopamine after hypoxia.[6] The effects on neurotransmission are those

of nonspecific modulation, which may be due to

the ability of piracetam to restore neuronal membrane fluidity, a property recently demonstrated in

aged mice.[7] Piracetam is thought to act on the central mechanism of balance.[2] Its effects are most

pronounced during aging,[3-5,8,9] and in the presence of

hypoxia.[6-8]

Clinical studies in humans have demonstrated

that piracetam may improve learning and memory

disorders [10-13] Dramatic improvements in cortical

myoclonus have been seen with high-dose

piracetam treatment.[14] Piracetam has also been reported to improve vertigo[15-18] and to provide significantly greater symptom relief than placebo in

vertigo resulting from head injury[15,16] and vertigo of

central origin.[l7] Haguenauer.[18] showed that

piracetam reduced the disability related to vertigo

of both peripheral and central origin. These studies

suggest that piracetam may accelerate spontaneous

recovery in patients with acute vertigo, and reinforce and stabilise adaptation when the symptom is

chronic. It appears to enhance the normal processes

of vestibular compensation[19] - recovery of oculomotor and postural function - in patients with both

peripheral and central vertigo. Such a mode of

action provides a logical approach to symptomatic

treatment, which is distinct from that of other

agents, in particular that of vestibular suppressant

drugs.

We therefore undertook the present study in a

group of middle-aged and elderly patients with

chronic vertigo of either peripheral or central origin to test this hypothesis and to confirm previous

observations relating to the efficacy and safety of

piracetam in chronic and recurrent vertigo.

© Adis international Limited. All rights reserved.

Study Design

The study design was double-blind and placebocontrolled with parallel groups in patients with

chronic vertigo. To permit the inclusion of an

adequate number of patients, the study was

multicentred and carried out in ear, nose and

throat clinics in Sweden (Uppsala, Gothenburg,

Linkoping, Lund), The Netherlands (Amsterdam),

the United Kingdom (Liverpool, Belfast) and

Belgium (Brussels).

Written informed consent was obtained for all

patients, and the protocol was approved by local

ethical committees and by Swedish and British

health authorities.

Patients

143 outpatients of either gender (84 female,

59 male) aged between 23 and 89 years (mean age

62 years) with chronic vertigo of at least 3 months'

duration and with 3 or more acute episodes or exacerbations each month, were enrolled in the study.

Vertigo was severe enough to interfere with social

and/or professional life. The diagnosis was clinical, and included detailed otological and neurological investigations established by each participating investigator according to criteria agreed

between the study centres.

Vertigo was defined as an illusion of rotatory

and/or nautical movement. Some patients had

chronic vertigo characterised by almost continuous symptoms of variable severity punctuated by

periodic exacerbations or episodes. Other patients

were largely symptom-free between episodes of

vertigo. Those with vertigo or dizziness of cardiac,

orthoslatic or neoplastic origin or due to stress or

muscular tension were excluded from the study.

Patients were randomised to receive either

piracetam 800mg or placebo tablets of identical

appearance 3 tines daily for 8 weeks. Patients

were re-evaluated 4 weeks after completing study

treatment.

Clin. Drug Invest, 11 (5) 1996

Piracetam in Chronic Vertigo

Assessments

Efficacy was evaluated by both patient and

physician. The primary outcome measures were

the frequency and seventy of episodes of. vertigo

assessed by patients.

By the Patient

Symptoms were evaluated by patients before

the start of treatment (baseline) and every 2 weeks

throughout the 8-week study period and for the ensuing 4 weeks. Evaluations at 4, 8 and 12 weeks

were used to determine efficacy. Patients were

asked about the frequency of episodes of vertigo

and about the length of time that episodes prevented normal activities.

Visual analogue scales (VAS) were used to assess severity both of the episodes and of any associated nausea and vomiting. The left extreme of the

VAS indicated that the symptom was absent, and

the-right extreme that it was severe. Well-being

between episodes was evaluated by VAS for the

severity of malaise, imbalance and difficulty with

walking.

At each visit, patients were also asked to give

ah overall assessment of their condition as 'improved', 'unchanged' or 'worse' compared with

the previous visit.

By the Physician

Investigators evaluated each patient at baseline,

after 4 and 8 weeks' treatment, and again at 12

weeks, i.e. 4 weeks after completion of treatment.

Detailed neurological and otological examination,

in addition to general physical examination, was

performed at baseline to confirm the diagnosis.

Specific otoneurological parameters were studied

including assessment of spontaneous, gaze and

positional nystagmus and smooth pursuit eye

movements. These were repeated when clinically

relevant. Physicians rated each patient's condition

as 'improved', 'unchanged' or 'worse' based on

the results of these examinations and patients'

report.

Overall evaluation compared with the

previous month by patient and physician were

recorded at each visit. Both were combined to

provide a global

Adis International Limited. All rights

reserved.

253

evaluation at the end of the 8-week treatment

period.

Safety

Details of all adverse events were recorded, as

were systolic and diastolic blood pressures and the

intake of concomitant drugs at baseline and during

treatment. The investigator was asked to record

whether the patient reported headache, sweating,

palpitations or anxiety as well as the response to

nonspecific questions.

Statistical Analysis

Data from all patients were included in an intention-to-treat analysis of patient self-evaluation

variables and overall assessments by patients and

physicians. We substituted data from the last available visit if later data were missing. Data from

patients who completed the study according to the

protocol ('evaluable' patients) were also analysed.

Changes from baseline after 4, 8 (end of treatment) and 12 weeks were calculated; the effects of

treatment were compared with changes from baseline because considerable interindividual variability rendered direct comparison of measured variables uninformative.

Efficacy variables were analysed for all patients

and for 3 patient subgroups: those with Meniere's

disease, those with vertigo of peripheral origin not

experiencing Meniere's disease, and those with

vertigo of central origin.

The Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyse

quahtitative variables because none had a normal

distribution. Qualitative variables were analysed

using either a 2 test or Fisher's exact test depending

on sample size; p values were computed as 2tailed and the level of significance was 5%. For

the 2 primary outcome parameters-frequency and

severity of vertigo episodes - a Bonferroni correction was applied, reducing the significance level

for these variables to 3%.

Analyses were performed using an SAS statistical package.

Clin. Drug Invest, 11 (5) 1996

Rosenhall et al

254

Table I. Demographic and baseline characteristics of study population (n= 143)

significantly greater and malaise between episodes

significantly more severe in the piracetam group.

The 2 groups were, however, comparable in other

respects (table III).

Outcome

Results

Of 143 patients enrolled in the study, 70 were

randomised to treatment with piracetam and 73 to

placebo. Patients' characteristics at baseline, including the aetiology of vertigo, are summarised in

table I. More women than men were included and

most patients were middle-aged or elderly.

89 patients fulfilled protocol requirements and

completed the study. Data were not evaluable in

54 who withdrew from the study because of either

adverse events, withdrawal of patient consent or

unacceptable protocol deviations including 9

patients whose compliance with treatment, assessed by tablet counts of unused medication, was

inadequate (table II). Withdrawals caused by adverse events were equally distributed between

piracetam and placebo groups.

The manifestations of vertigo present on entry

are summarised in table III. Significant baseline

differences between treatment groups: were found

in 2 parameters: the mean frequency of acute episodes during the 2 weeks prior to the study was

© Adis International Limited. All rights reserved.

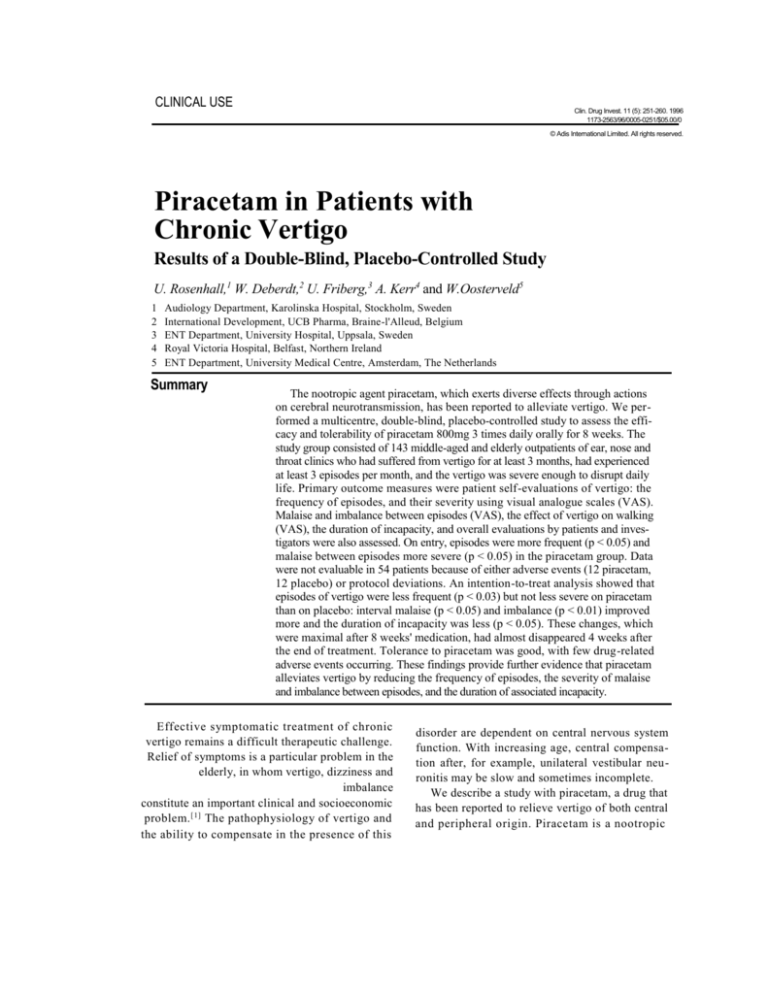

After 8 weeks of treatment, we found fewer

episodes of vertigo in the piracetam group coppared with placebo (p < 0.03, significant after

Bonferroni correction), but no difference in their

severity (fig. 1).

Malaise (p < 0.05) and imbalance (p < 0.01)

between episodes improved more and the duration

of incapacity was less (p < 0.05) on piracetam than

on placebo (fig. 1). We were unable to find significant differences between treatment groups in the

other parameters measured: nausea and vomiting

during acute episodes or the effect of vertigo on

walking, or in global evaluation by patients or

physicians.

Improvements in the piracetam group seen at

the end of treatment had largely disappeared at

follow-up 4 weeks after cessation of therapy

(fig. 1). Although episodes still occurred less often

than at baseline, the difference from placebo was

no longer significant. Apart from sustained improvement in malaise compared with placebo, we

were unable to find differences from baseline in

interval severity of imbalance or in duration of incapacity.

Table II. Reasons for exclusion from the 'evaluable' population

Clin. Drug Invest. 11 (5) 1996

255

Table III. Baseline frequency and severity of vertigo in treatment groups. Data are presented as means ± standard deviations. Values

are given for number of episodes (primary outcome parameter), severity of episodes (primary outcome parameter) and of associated

nausea and vomiting, manifestations between episodes (malaise, imbalance, effect on walking), and days of incapacity Parameter

Baseline values

piracetam (n = 70)

placebo (n= 73)

16.8(25.8)

8.8(18.8)

(23.9)

p value No. of episodes of vertigo during previous 2 weeks

<0.05 a Severity of vertigo (VAS in mm) during previous 2 weeks

45.5 (22.7)

29.4(33.8)

NS Severity of nausea and vomiting during attacks (VAS i n mm)

NS Between episodes Severity of malaise (VAS in mm)

<0.05a Severity of imbalance (VAS in mm)

23.7(23.1)

31.3(27.0)

34.2(28.4)

33.1(26.0)

NS Effect of walking (VAS in mm)

NS Duration of incapacity during previous 2 weeks (days)

44.4

23.8(31.4)

31,7(25.4)

3.9(5.0)

34.0(26.6)

2.6(3.7)

NS a

Significant differences.

Abbreviations: NS= nonsignificant; VAS = visual analogue scale.

Table IV. Changes from baseline in patients with Meniere's disease after 8 weeks' treatment. Data are presented as means ± standard

deviations and significance levels. Values are given for number of episodes (primary outcome parameter), severity of episodes (primary

outcome parameter) and of associated nausea and vomiting, manifestations between episodes (malaise, imbalance, effect on walking) and

days of incapacity

Parameter

piracetam

placebo

4.8 (11 .6)

12.6 (31 .5)

5.0 (20.4)

-9.0 (33.9)

17.7(39.3)

•• . . . ,-13.1(26.8).

After 8 weeks' treatment

p value No. of episodes of vertigo in preceding 2 weeks

'

-17.3(28.9)

4.4(18.3)

4.8(19.8)

0.04 a Effect on walking (VAS in mm)

5.3(22.4)

-4.7(26.2)

0.52 Duration of incapacity in previous 2 weeks (days)

-0.4(5.4)

0.40 a Significant differences.

70 12

.

73 12

-

0.68 Between episodes Severity of malaise (VAS in mm)

•

0.07 Severity of imbalance (VAS in mm)

-5.3(17.1)

2.0(4.4)

-

0.02a Severity of vertigo (VAS in mm) during previous 2 weeks

0.68 Severity of nausea and vomiting during episodes (VAS in mm)

When we analysed data from the 89 'evaluable'

patients who completed the study and met protocol

requirements, they were found to confirm the results of intention-to-treat analysis. Compared with

placebo, there were fewer episodes of vertigo with

no difference in their severity.

There was improvement in the duration of

incapacity and, in the intervals between episodes,

in malaise and imbalance (fig. 2). Analysis of

physicians' global evaluations showed more improvement on piracetam than in the placebo group

(p < 0.05). In addition, the improvements on piracompared with placebo, which were highly

-

significant after 8 weeks' treatment, had, apart

from the frequency of vertigo episodes, disappeared at follow-up 4 weeks after completion of

treatment (fig. 2).

Meniere's disease: The pattern of response in

patients with Meniere's disease was similar to that

of the whole group. There was a statistically significant improvement after 8 weeks' treatment;

episodes of vertigo were less frequent, while

imbalance between the episodes was less severe

(table IV). Other parameters showed no significant

change.

Adis International Limited. All rights reserved.

Clin. Drug Invest. 11 (5) 1995

Rosenhall et al.

256

a Change from baseline after 4 weeks (n = 143)

b Change from baseline after 8 weeks (n = 143)

c

Change from baseline after 12 weeks [4 weeks after

cessation of treatment] (n = 143)

Fig. 1. Intention-to-treat analysis. Changes from baseline in patient self-evaluation parameters after (a) 4 and (b) 0 weeks' treatment

with piracetam or placebo and (c) at 12 weeks, 4 weeks after the end of treatment. Data are presented as means and standard errors

of the mean (SEM). Changes shown are the number of attacks of vertigo and the number of days of incapacity compared with the

preceding 2 weeks. Changes in other parameters are expressed in mm on the visual analogue scales (VAS), where negative valuesindicate improvement.

© Adis International Limited. All rights reserved,

Clin. Drug Invest. 11 (5) 1996

Piracetam in Chronic Vertigo

We found some trends suggesting a similar pat

tern of response in those with peripheral vertigo

without Meniere's disease and in patients with ver

tigo of central origin, but the numbers were too

small for analysis.

Tolerability

Treatment tolerability was similar in the

piracetam and the placebo patients. 30 patients

receiving piracetam and 27 on placebo reported

a

257

adverse events. In response to specific questioning,

headache, sweating, palpitations and anxiety were

reported with similar frequency in both groups and

consistently less often than at baseline.

Adverse events led to withdrawal from the

study in 12 patients in each group (table V). Exacerbation of nausea or vertigo was more frequent

with placebo than with piracetam. One patient discontinued treatment because of anxiety, panic attacks and agitation, which were probably drug

related because agitation and related mood distur-

Change from baseline after 8 weeks. Evaluable patients (n = 89)

b Change from baseline after 12 weeks (4 weeks after cessation

of treatment). Evaluable patients (n = 89)

Fig, 2, Analysis of 89 'evaluable' patients. Changes from baseline in patient self-evaluation parameters after (a) 8 weeks' treatment

with piracetam or placebo and (b) at 12 weeks, 4 weeks after the end of treatment. Data are presented as means and standard errors

of the mean (SEM). Changes shown are the number of attacks of vertigo and the number of days of incapacity compared with

the

preceding 2 weeks. Changes in other parameters are expressed in mm on the visual analogue scales (VAS) where negative values

indicate improvement.

Rosenhall et

al.

258

Table V. Adverse events leading to withdrawal from the study

Adverse event

Piracetam

Placebo

Exacerbation of vertigo or nausea

3

5

Manisfestation of pre-existing or

6

7

concomitant disorder Anxiety, agitation, panic attacksa

1

Diarrhoeab

1 Intracranial

haemorrhage with

1 hemiparesisb

Total

12

12

a Probably drug related. b Not considered drug related (see

text).

bances have been documented with piracetam.[20]

Diarrhoea, which caused the withdrawal of 1

patient, was judged to be unrelated to therapy. A

haemorrhagic stroke with a right hemiparesis,

which caused withdrawal from the study on day 40

of one 74-year-old piracetam-treated female

patient with mild hypertension, was not considered

drug related.

No clinically relevant abnormalities were found

in routine laboratory safety parameters, and minor

abnormalities in piracetam-treated patients were

seen with a frequency similar to that at baseline.

Discussion

These findings in-patients with chronic or recurrent vertigo suggest that, compared with placebo,

piracetarn provided symptomatic improvement by

reducing the number of acute episodes and by

improving malaise and imbalance in the intervals

between episodes. We did not show an effect of

piracetam on the severity of vertigo.

Several factors must, however, be taken into

account in interpreting the significance of these

results. Problems in clinical studies of vertigo

include the selection of sufficiently rigorous diagnostic criteria for patient inclusion, recruitment of

enough patients who meet these criteria, and the

adoption of sufficiently reliable and reproducible

methods of assessment.

We included patients with vertigo of both

peripheral and central origin because of positive

© Adis Internationa! Limited. All rights reserved.

findings in previous studies with piracetam[15-18] and

its postulated central action on the vestibular and

oculomotor nuclei.[2]

Criteria for the diagnosis of rotatory or nautical

vertigo were strict, so that, despite the frequency

of vertigo in an elderly population and the inclusion of 8 study centres, a period of 3 years was

necessary to study enough eligible patients. Evaluation of the symptom of vertigo is necessarily

subjective. We chose a series of measures involving patient self-assessment, the most important of

which were the frequency and severity of episodes

of vertigo.

The 2 treatment groups were not entirely comparable prior to treatment in that episodes of vertigo were more frequent in the piracetam group and

the malaise between episodes was worse. It might

therefore be argued that improvement was due to

adaptation and spontaneous improvement, with

regression to the mean, which commonly occurs in

vertigo.[19]

However, several factors suggest that the

changes were due to piracetam. Only patients with

'recurrent vertigo of at least 3 months' duration

were included. In addition, the baseline differences

between treatment groups, i.e. more episodes in

piracetam-treated patients, were more marked in

those patients who completed the study and in

whom response could be assessed than in the total

patient group. This probably indicates the withdrawal of some patients on placebo because of a

lack of efficacy.

A further observation was that the condition of

some patients deteriorated after piracetam was

stopped. This is apparent when response after 8

weeks' treatment is compared with that at 12

weeks, i.e. at follow-up 4 weeks after cessation of

treatment. The between-group difference in the

frequency of episodes, improvement in interval

imbalance and in the duration of incapacity seen

after treatment for 8 weeks had almost entirely disappeared 4 weeks later. This pattern, which was

evident in the intention-to-treat analysis and to a

certain extent also in the analysis of those patients

Clin. Drug Invest. 11 (5) 1996

Piracetam in Chronic Vertigo

who completed the study, is consistent with a drug

effect.

The finding of positive effects of piracetam in

patients with chronic or recurrent vertigo are in

broad agreement with those in other double-blind,

placebo-controlled studies in patients with vertigo

of various aetiologies. Significant improvement in

vertigo and other symptoms has been reported in

patients with subacute or chronic symptoms after

head injury,[15,16] and in those with troublesome

vertigo of central origin. [17] Haguenauer, in a double-blind study versus placebo in 50 patients with

vertigo of labyrinthine or retrolabyrinthine origin,

reported marked improvement in the severity of

vertigo and associated symptoms and disability.[18]

The improvements reported in these studies are

generally consistent with the results of our trial,

and indicate a beneficial effect of piracetam on the

symptom of vertigo.

That piracetam provides symptomatic relief in

elderly patients is of particular relevance because

of the greater frequency of vertigo in this age group

and the untoward effects of sedative and antihistaminic agents, which inhibit input from the vestibular apparatus.[20] Adaptive mechanisms become

less responsive in the elderly and may be less

effective in compensating for peripheral vestibular

disorders.[21]

The effect of piracetam on vertigo appears to be

prophylactic in that it diminishes the number of

episodes or exacerbations and improves background symptoms between episodes. These observations are consistent with the postulated effects of

piracetam on neurotransmission and the central

mechanisms for the control of balance, and are relevant not only in vertigo of central origin but also

to adaptation and restoration of balance in peripheral vestibular disorders.[20]

Piracetam possesses an unusually benign adverse effect profile, and its tolerance has been repeatedly shown to be good.[20,22] That adverse

events were frequent and the dropout rate high in

both treatment groups in the present study is partly

a reflection of the frequency of concomitant disorders in this predominantly elderly population in

Adis International Limited. All rights reserved.

259

which vertigo often represents a manifestation of

underlying pathology. Agitation and disturbances

of mood have been described with piracetam.[20,22]

and one such instance in this study was probably

drug related.

The occurrence of intracranial bleeding and

hemiparesis in one patient, which was not considered drug related, was, however, a serious adverse

event. In this patient vertigo of central origin probably reflected underlying cerebrovascular disease.

There have been no reports of intracerebral or subarachnoid bleeding after piracetam despite its

widespread use in patients with cerebrovascular

disease and in the treatment of ischaemie stroke.

Although piracetam decreases platelet aggregation

and has been reported to cause slight prolongation

of bleeding time,[23] this occurs only at dosage

levels much higher than those given to these

patients and has not been associated with clinical

consequences.

Conclusions

We have provided further evidence, in a group

of predominantly elderly patients with vertigo,

that piracetam provides symptomatic relief by

reducing the frequency of episodes, the severity of

malaise and imbalance between episodes, and the

duration of associated incapacity. Piracetam was

well tolerated and free from serious adverse events.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all those who contributed to the study

and, in particular, the following investigators: Dr J. Stahle,

Dr L. Odkvist, Dr M. McCormick, Dr M, Magnusson.

Dr T. Mets, Dr C. Erwall Dr H.W. Kortschot, Prof. G. Liden.

Dr H. Rask-Andersen, Dr R. Rudin, Dr M. Karlberg,

Prof. P. Clement, and the study coordinator. Mr E. Trippas.

This project was supported by a grant from UCB Pharma.

References

1. Sixt E, Landahl S. Postural disturbances, ima 75-year-old population: prevalence and functional consequences. Age Ageing

1987; 16: 393-8

2. Giurgea C. Piracetam: nootropic pharmacology of neurointegrative activity. Curr Develop Psychopharmacol 1976; 3:

222-73

3. Stoll L, Schubert T, Muller WE. Age-related deficits of central

muscarinic

cholinergic receptor

function in the

mouse: partial

Clin, Drug Invest. 11 (5) 1996

260

restoration by chronic piracetam treatment. Neurobiol Aging

1991; 13:39-44

4. Cohen SAt Muller WE. Effects of piracetam on N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor properties in the aged mouse brain. Pharmacology 1993; 47: 217-22

5. Canonico PL, Aronica E, Aleppe G, et al. Repeated injections

of piracetam improve spatial learning and increase the stimulation of inositol phospholipid hydrolysis by excitatory

amino acids in aged rats. Fund Neurol 1991; 6 (2): 107-11

6. Wustmann Ch, Fischer HD, Schmidt J. The effect of piracetam

on post-hypoxic dopamine release inhibition. Acta Biol Med

German 1982; 41: 729-32

7. Muller WE, Hartmann H., Koch S, et al. Neurotransmission in

aging - therapeutic aspects. In: Racagni G, Brunello N, Langer SZ, editors. Recent advances in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders and cognitive dysfunction,

International Academy for Biomedical and Drug Research.

Basel: Kager, 1994:7: 166-73

8. Giurgea C, Mouravieff-Lesuisse F. Central hypoxia models and

correlations with aging brain. In: Deniker P, RadoucoThomas C, editors. Neuropsychopharmacology, 1978: 2:

1623-31

9. Giurgea C, Greindl MG, Preat S, Nootropic drugs and aging.

Acta Psychiatr Belg 1983; 83: 349-58

10. Dimord SJ, Brouwer EYM. Increase in the power of human

memory in normal man through the use of drugs. Psychopharmacologia 1976; 49: 307-9

11. Wilsher C. Piracetam and dyslexia - effects on reading tests, J

Clin Psychopharmacol 1987; 7 (4): 230-7

12. Vernon MW, Sorkin.EM, Piracetam - an overview of its pharmacologic properties and a review of its therapeutic u.se in

senile cognitive disorders. Drugs Aging 1991; 1 (1): 17-35

13. Croisile B, Trillet M, Fondarai J, et al. Long-term and high-dose

piracetam treatment of Aizehimer's disease. Neurolouy 1993;

43:301-5

14. Brown P, Steiger MJ, Thompson PD, et ai. Effectiveness of

piracctam in corfical myoclonus. Mov Disord 1993; 8 (1):

63-8

Adis International Limited. All rights reserved.

Rosenhall et

al.

15. Aantaa E, Meurman OH. The effect of piracetam (Nootropil

6215) upon the late symptoms of patients with head injuries.

J Int Med Res 1975; 3 (5): 352-5

16. Hakkarainen H, Hakamies L. Piracetam in the treatment of

postconcussional syndrome. A double-blind study. Eur Neurol 1978; 17:50-5

17. Oosterveld WJ. The efficacy of piracetam in vertigo. A doubleblind study in patients with vertigo of central origin.

Arzneimittel Forschung 1980; 30(II), 11: 1947-9

18. Haguenauer JP. Essai clinique du piracetam dans le traitement

des vertiges. Etude controlee versus placebo. Les Cahiersde

I'Oto-Rhinc-Laryngologie 1988; 21 (6): 460-6

19. Norre ME. Dysfunction and cerebral adaptation. In: Posture in

otoneurology. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 1990; 44 (2) II:

139-81

20. Salliez AC, Delaere A. ADR profile of piracetam. Post-marketing surveillance. Review of data collected through spontaneous reporting ti ll end December 1994. UCB Pharma: 1995.

Report No: A RVE95D1901

21. Norre ME. Aged persons: geriatric problems. In: Posture in

otoneurology. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Belg 1990; 44 (2) IV;

309-20

22. Delaere A, Salliez AC. Safety profile of piracetam in doubleblind studies. UCB Pharma: 1994, June. Report No:

ARVE94FZ3I2

23. Moriau M. Crasborr. L, Lavenne-Pardonge E, et al. Platelet antiaggregant and rheologic properties of piracetam. A pharmacodynamic study in normal subjects. Arzneimittel

Forschung 1993; 43 ( I) : 110-8

Correspondence and reprints: Dr Walter Deberdt, UCB

Pharma, International Development Chemin du Foriest,

B-1420 Braine-l'Alleud, Belgium.

Clin. Drug Invest. 11 (5) 1996.