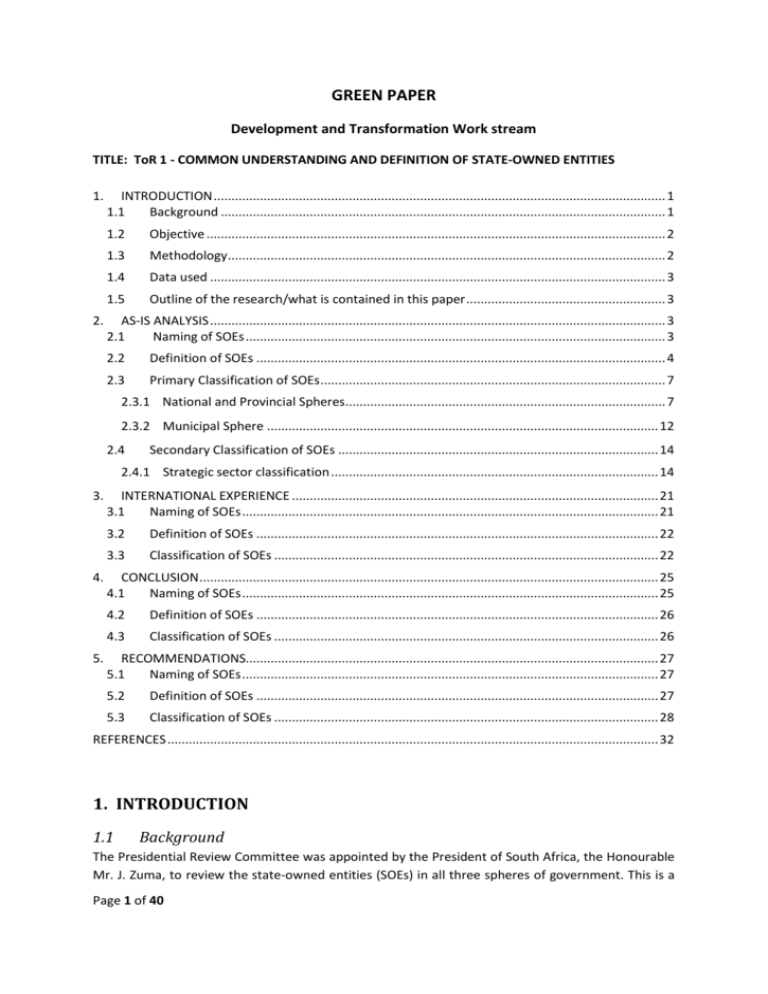

A common understanding and definition for SOEs

advertisement