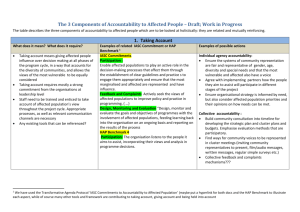

Accountability to Affected Populations

advertisement

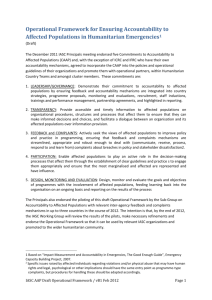

INTER-AGENCY STANDING COMMITTEE XYZ MEETING Accountability to Affected Populations: An Operational Framework DD MMMM YYYY Rome Circulated DD MMMM YYYY I Introduction At their meeting in April 2011, the IASC Principals acknowledged the fundamental importance of accountability to affected populations. They agreed to integrate accountability to affected populations into their individual agencies' statements of purpose as well as their policies. Further, they requested that the Sub Group on Accountability to Affected Populations (part of the IASC Cluster Sub Working group) in consultation with HAP, SPHERE, CDAC, national governments and other relevant initiatives develop a proposal for inter-agency mechanisms that would enable improved participation, information provision, feedback and complaints handling. The Sub Group held an initial consultation with a number of actors in early July. Invitees included organizations directly involved in developing standards or systems to strengthen humanitarian accountability, donor representatives and representatives from various UN agencies, IOs and NGOs, including those with cluster leadership responsibilities. The Sub Group have completed a draft operational framework1 based on cumulative lessons learnt, best practices, and experience from past and ongoing projects from a variety of humanitarian organisations. Several field pilots are being planned to validate and strengthen the framework. SPHERE standards, Humanitarian Accountability Partnership (HAP) benchmarks or other methodologies provide a means of verification of the operational framework. An outline of potential collective feedback and complaints mechanisms is also described, with arguments in favour and others against using particular methodologies. A short list of “collective commitments” was also considered, aimed at providing a common baseline for agencies to elaborate or enhance accountability, to monitor that accountability and to provide coherence and a clear understanding of what accountability to affected populations really means. II Operational Framework The operational framework2 that has been developed by the Sub Group is aimed at field practitioners and therefore is structured around the program framework. Clearly an operational framework for accountability to affected populations that is understood and used by IASC and partner organizations cannot be effective if it is divorced from the overall humanitarian architecture, and therefore clusters and 1 2 An outline of the framework can be found in the Annexe to this paper. Idem 1 the current humanitarian response architecture has also been taken into consideration. What is also clear however is that, whether implemented through clusters or other joint programming arrangements, improved accountability can only be as effective as the capacity and willingness of individual organisations to uphold their responsibilities. If an “accountability to affected populations” approach is to be adopted by the humanitarian system as a whole, it will require that organizations, their partners as well as donors endorse this approach to engage with communities in a more systematic way. Organizations need to adapt their programming; including those of their partners; donors need to provide more flexible funding lines for programming to be adequately adapted. What is being suggested is in fact a modification or change in guidance and rules in some cases and in others a shift in behaviour and culture. Given the diverse contexts within which humanitarian organizations work, the operational framework as described below3 needs to be applied in a flexible manner, and adapted to the context as necessary. In order for the framework to be of practical use, minimum standards also need to be integrated. The HAP and SPHERE standards have been reflected in the framework, making best use of an existing in-depth, cross sectoral consultation process that has developed the standards. A more detailed framework will be made available for the proposed field pilots. III Accountability to Affected Populations at Policy level There are many variations in the understanding of what accountability to affected populations is. This has been demonstrated by different approaches within organizations, but also by the number of separate initiatives, albeit from different perspectives, to achieve greater accountability. It would be therefore useful to have a shared understanding of the broad tenets of accountability to affected populations. This is why it is proposed that several commitments (building on the existing work of the Emergency Capacity Building project (ECB)4) be put forward to the IASC Principals for the inter-agency community to endorse and promote. Not unlike the “Principals of Partnership”, these commitments can then be used within country strategies, programme proposals, staff inductions, partnership agreements, Letters of Understanding or even by the cluster themselves, to help ensure more systematic understanding and implementation of activities that address accountability. This said accountability cannot be fully captured in a checklist of commitments; it is not a programmatic technical process but is rather built on the nature of the relationship between “receiver” and “provider” of assistance both prior to and following an emergency. The proposed commitments must therefore be seen as some initial steps that will encourage and, where needed, force a firmer commitment from the management and staff of organisations to act in to act in such a way that accountability in humanitarian response is mandatory rather than an element of humanitarian rhetoric. The commitments can be assessed based on agreed upon indicators and progress can be followed in evaluations and reviews. Based on “Impact Measurement and Accountability in Emergencies, The Good Enough Guide”, Emergency Capacity Building Project, 2007. 4 The Good Enough Guide: Impact Measurement and Accountability in Emergencies, Emergency Capacity Building project, 2007 3 2 In addition, by articulating a common understanding of what it is to be accountable to affected populations, there be a clearer basis upon which to have a dialogue with a broader set of humanitarian actors, beyond the IASC, including national NGOs, CBOs, host governments and donors. By agreeing to commitments it will also be easier to expect and promote accountability to affected populations. Suggested Commitments for Accountability to Affected Populations LEADERSHIP/GOVERNANCE: Demonstrate their commitment to accountability to affected populations by ensuring feedback and accountability mechanisms are integrated into country strategies, programme proposals, monitoring and evaluations, recruitment, staff inductions, trainings and performance management, partnership agreements, and highlighted in reporting. TRANSPARENCY: Provide accessible and timely information to affected populations on organizational procedures, structures and processes that affect them to ensure that they can make informed decisions and choices, and facilitate a dialogue between an organisation and its affected populations over information provision. FEEDBACK and COMPLAINTS: Actively seek the views of affected populations to improve policy and practice in programming, ensuring that feedback and complaints mechanisms are streamlined, appropriate and robust enough to deal with (communicate, receive, process, respond to and learn from) complaints about breaches in policy and stakeholder dissatisfaction5. PARTICIPATION: Enable affected populations to play an active role in the decision-making processes that affect them through the establishment of clear guidelines and practice s to engage them appropriately and ensure that the most marginalised and affected are represented and have influence. DESIGN, MONITORING AND EVALUATION: Design, monitor and evaluate the goals and objectives of programmes with the involvement of affected populations, feeding learning back into the organisation on an ongoing basis and reporting on the results of the process. IV Challenges and Risks As a humanitarian community, to be truly accountable to affected populations, all stakeholders within the system must adapt their programming and systems to ensure consistent and ongoing consultation, communication, and programming that is adaptable to the needs of the relevant communities. It also requires flexibility to change the direction of a project or a program if it is not meeting the needs of the affected populations. Organizations need to adapt their programming; including those of their implementing partners; donors need to provide more flexible funding lines. Donors, as stakeholders in the humanitarian system must also ensure that there funding lines are flexible enough to adapt to feedback and/or complaints from affected populations. As mentioned above, what is being suggested is in fact a modification or change in programme guidance and procedures in some cases and in others a shift in behaviour and culture. An added challenge is the coordination of messages and mechanisms to avoid communication overload and/or the provision of conflicting information. 5 Specific issues raised by affected individuals regarding violations and/or physical abuse that may have human rights and legal, psychological or other implications should have the same entry point as programme-type complaints, but procedures for handling these should be adapted accordingly. 3 One particular and often discussed component of accountability to affected populations that may pose complex challenges are joint feedback and complaints mechanisms. Effective feedback and complaints mechanisms require a clear referral system to the organization that receives the feedback or complaint and, in the case of a complaint, a clear system for investigating that complaint and taking timely and appropriate action. If, in the case of a joint system, a participating organization that is not adequately responsive, what was initially feedback can become a complaint. If there is a failure to address a complaint, this can become an even more serious issue and pose a threat to all organizations working in a community. Everyone is at risk of being seen as equally culpable. There are good practice examples in many countries, but these experiences must be captured and replicated more systematically. For these reasons, complaints and feedback mechanisms have been separated from the Operational Framework in this document. Different models are listed in the next section. V Models for joint Feedback and Complaints Combining Feedback and complaints into one system encourages both positive and negative issues to be communicated and also demonstrates an openness to listen to all concerns being voiced, forming a critical aspect of the dialogue between humanitarian organizations and affected populations. Regardless of what feedback complaints mechanism is chosen however, and how it is introduced in a community, if a serious concern is raised, the organisation that needs to address this complaint must have the required internal systems in place. There needs to be management buy-in from all the agencies concerned as well as from the HC/RC in country. Feedback and Complaint Mechanisms: Advantages and Disadvantages Mechanisms Local agencies/Ombudsman6 Trusted local agencies or an independent individual collect feedback and pass it on to the Organization Cluster Cluster Coordinators are trained and establish system for and by the cluster with affected populations Advantages Disadvantages • Communities may be more honest with intermediaries than with the agency giving aid • Can be manipulated by the local agency • Reinforces community structures • People excluded by existing power structures may continue to be excluded • Transparent process that the Organization accepts and responds to complaints • If an independent individual is appointed, this may incur additional stand alone costs • Cluster Coordinator is already involved in coordinating and shaping the sector wise response • Success dependent on selection of commitment of the Cluster Coordinator and buy in from members of the Cluster/ HCT. • Problems can be solved by the cluster members • Requires time and investment to set up, including training of staff and resources for them to use. Based on the World Vision International. 2009, “Complaint and response mechanisms: a resource guide, first edition”. Monrovia, U.S.A, p57. 6 4 Capacity Development Exercise in Country • The team that is working together is trained together in the relevant tools within context Training/ capacity development support is made available at the country level. • A context established specific system is • Such training would need to be replicated at each emergency • Requires time and investment to set up, including training of staff and resources for them to use. Mechanisms for the feedback and complaints also need to be established. All methods used also have both positive and negative aspects. They range from establishing a Community Help Desk where a group of community members who receive complaints at meetings and distributions; an Office day, or regular time per week allocated for communities to come to the office to give feedback or make a complaint; a suggestion box which is a locked box for receiving complaints and feedback that would include options for the illiterate e.g. access to tape recorder and tapes or literate volunteers. Telephone or SMS systems have also been used, where a telephone number is published for receiving feedback and complaints. All these system require resources, and once established a mechanism for providing the feedback or complaints to the relevant organizations7. VI Pilot Countries There already has been some informal discussions with ECB and we will be able to take advantage of already planned and funded projects to make field based recommendations on the best way forward Further discussion is needed and other pilot options are also being explored. VII Requested Action by IASC Working Group: The IASC Cluster SWG requests the following for IASC WG’s consideration and endorsement: IASC WG agrees that the Sub Group on Accountability to Affected Populations will propose to the Principals Task Team in December: That the IASC organizations commit to promoting the Accountability to Affected Populations Commitments within their own agency, with operational partners, within HCTs and amongst cluster membership; That the operational framework be piloted with relevant inter agency feedback and complaints in several countries for further validation and refinement; That once piloted, reviewed and endorsed by the IASC that the IASC organizations use and promote the Operational Framework. Please see World Vision International. 2009, “Complaint and response mechanisms: a resource guide, first edition”. Monrovia, U.S.A, p57 for more details of possible options. 7 5 ANNEXE Operational Framework for Ensuring Accountability to Affected Populations in Humanitarian Emergencies (summarised version) Phase Throughout all phases of the program cycle: System wide learning and establishing means of mainstreaming and verification Throughout all phases of the program cycle: Systematically communicate with affected populations using relevant feedback and communication mechanisms Responsibility Activities Challenges Individual Organizations/ Coordination bodies (OCHA, NGO Consortia, Clusters, HCT) Humanitarian organizations, clusters, HC (supported by OCHA), HCT Mainstreaming accountability Initiate a dialogue with donors Time and resources Management buy-in Adequate skills and capacity Open up existing humanitarian information systems Develop and/or support multi-agency response communications initiatives Implement communications projects that already deliver on a response-wide level Need to further develop system-wide communications coordination function and methodology for collating feedback Feedback processes often only focus on project-level information Tools Means of verification HAP Standard Benchmark 18 Feedback on progress made through IASC HAP Standard Benchmark 3, 4 and 5 Affected populations have access to information, possibility to provide feedback and receive response Humanitarian funding mechanisms adapted 8 The HAP Standard Benchmarks 1 refers to Establishing and delivering on commitments; 2 refers to Staff competency, 3 refers to Sharing information, 4 to Participation and 5 to Handling complaints. Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) 6 Before assessment and/or during contingency planning During assessment During project design and/or response planning 9 NATF/ Needs Assessment Teams in the Field/ Clusters/ Inter Cluster mechanisms/ Individual organizations Clusters/ Inter Cluster mechanisms/ Individual organizations Clusters/ Inter Cluster mechanisms/ HCT /Individual organizations Include accountability in job descriptions, staff development and appraisals Inform local communities Adapt communications to local culture/ customs Deploy Q&A officers at the beginning of response as a cross-cutting capacity Allow for separate and private discussions with different community groups Describe methodology to communities Feedback and complaints mechanisms established Integrate the activities above in any joint needs assessment planning Share findings of assessment within the humanitarian community and with affected populations Involve local community in project design Design complaints and response mechanism with Common commitment to accountability to affected populations Sufficient resources Ensuring common standards for Staff awareness Inclusion in staff and programme performance evaluation Reaching out to all community groups Creating an environment where people/groups can speak openly Communicating in local language(s) Managing expectations Ensuring that activities are measurable and transparent Ensuring that resources for accountability are included in country strategies and emergency appeals Reflect commitments in Include accountability into strategic and planning documents Include accountability principles and mechanisms in trainings, ToR, appraisals etc. HAP Standard Benchmark 2, 3, 4 and 5 Use of CAP indicators to monitor and evaluate the sector WFP’s Vulnerability Analysis and Mapping UNHCR’s Age, Gender and Diversity Mainstreaming methodology NATF and joint needs assessments HAP Standard Benchmarks 3, 4 and 5 Sphere Core Standard 3: Assessment, Key Indicator 19 Good practice examples of feedback and complaints mechanisms HAP Standard Benchmark 1, 2 and 6 Sphere Core Standard 1 and 2: Coordination and Collaboration: Key Indicator 410 and guidance note 1. Assessed needs have been explicitly linked to the capacity of affected people and the state to respond. The agency’s response takes account of the capacities and strategies of other humanitarian agencies, civil society organisations and relevant authorities (Guidance note: explicit efforts to listen to, consult and engage people at an early stage will increase quality and community management later in the programme) 10 Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) 7 local input During project implementation During distribution and service delivery During monitoring/ evaluation Clusters/ Inter Cluster mechanisms/ Individual organizations Clusters/ Inter Cluster mechanisms/ Individual organizations Clusters/ Inter Cluster mechanisms/ Individual organizations Local community groups assist in developing criteria for selection of beneficiaries Criteria and selection process is made public Implement complaints and response mechanism Gather feedback on the quality/accountability of the response Where relevant, form a distribution committee and/or consultative group Inform local communities in advance (security allowing) Invite local community representatives to take part in monitoring/evaluation process Share and discuss findings with local communities Hold an internal learning review partnership agreements Ensuring means to respond to feedback and to address complaints Respecting the privacy of individuals and providing means for confidentiality HAP Standard Benchmark 4 Public knowledge of feedback and complaints mechanisms Prioritization of vulnerable groups HAP Standard Benchmarks 3, 4 and 5 Analysis of feedback and complaints (trends in number and type of complaints and feedback received over time) Reporting in a timely manner to affected populations, partners, authorities, donors, etc. Feedback from communities HAP Standard Benchmark 3, 4 and 5 Sphere Core Standard 5: Performance, transparency and learning: Key Indicator 1 and 211 Sphere Core Standard 1, Key Indicator 312 11 Programmes are adapted in response to monitoring and learning information; Monitoring and evaluation sources include the views of a representative number of people targeted by the response, as well as the host community if different 12 The number of self-help initiatives led by the affected community and local authorities’ increases during the response period Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) 8 Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) 9