Questionnaires

advertisement

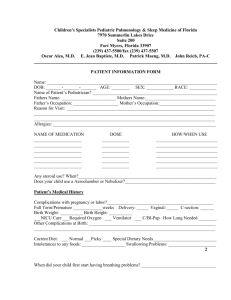

Nonadherence is Correlated to Poor Quality of Sleep in Diabetic Hemodialysis Patients Pei-Mei Chan1, Shu-Chen Huang1, Yu-Sen Peng2, MD, Ju-Yeh Yang2, MD* 1Nursing Department, Far Eastern Memorial Hospital 2Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Far Eastern Memorial Hospital Conflict of interest statement: The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part, except in abstract format. The authors, singly or collectively, have had no involvement that might raise the question of bias in the work reported. *Reprint requests and correspondence to: Ju-Yeh Yang No. 21, Nan-Ya S. Rd., Sec.2 Pan-Chiao, Taipei, Taiwan Telephone: +886-2-89667000, Fax: +886-2-89667000*1162 e-mail: yangjuyeh@gmail.com Running title: Sleep and adherence 1 中文摘要 長期血液透析的糖尿病患者的醫囑遵從性與睡眠品質相關 詹培梅 1、黃淑貞 1、彭渝森 2、楊如燁 2 亞東紀念醫院 1 護理部 2 腎臟內科 研究目的: 睡眠問題常造成長期血液透析患者的困擾,醫囑遵從性則是影響糖尿病 患者及透析患者預後的因子之一。本研究的目的在釐清睡眠問題與醫囑遵從性兩者之 間的關連性。 研究方法: 我們研究 76 位在台灣北部某一醫學中心長期血液透析的糖尿病患者, 蒐集其基本資料,利用匹茲堡睡眠品質問卷評估睡眠品質,醫囑遵從性則利用飲食控 制問卷、藥物數量計數及透析間體重增加來評估。 研究結果: 平均的睡眠品質分數為 9.7 ± 4.5。我們發現在有無睡眠困擾的兩組患者 間的基本性質及一般生化檢查沒有不同。主觀的飲食醫囑遵從性越好,透析間體重增 加越少,但兩者與藥物醫囑遵從性之間皆無相關性。主觀的飲食醫囑遵從性越好的患 者其主觀的睡眠品質越好。 結論: 睡眠及醫囑遵從性都是臨床上令醫病雙方困擾的棘手問題。我們報告兩者在 長期血液透析的糖尿病患者的關連性,暗示可能有一些共同影響的因子值得進一步探 討。 關鍵字: 糖尿病、血液透析、醫囑遵從性、睡眠品質 2 Abstract Objectives: Sleep disturbance is a common complaint of end-stage renal-disease (ESRD) patients. Nonadherence is popular and frustrating amongst diabetes (DM) and hemodialysis (HD) patients. This study examined the relationship between quality of sleep (QOS) and adherence for diabetes patients on HD. Methods: The study subjects included 76 diabetes patients undergoing regular hemodialysis in one medical center in Northern Taiwan. We collected biochemical parameters and demographic data. The quality of sleep was assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire. Adherence was measured by self reported questionnaires and pill counting. Results: The average PSQI score was 9.7 ± 4.5. There was no difference in all demographic or biochemical parameters between the good and the poor sleepers. The subjective diet compliance consisted with interdialytic weight gain (r=-0.331, p=0.004) but not medication adherence (r=-0.012, p=0.917). Patients with subjective better diet compliance slept better (r= -0.287, p=0.013). There was no correlation between medication adherence and quality of sleep (r=-0.039, p=0.740). Conclusions: Both nonadherence and sleep disturbance were challenging to deal with. The correlation between subjective quality of sleep and diet adherence amongst diabetic HD patients merits further research to explore potentially modifiable common factors. . Key words: dialysis, quality of sleep, adherence, diabetes 3 Introduction Patients undergoing long-term dialysis therapy consumed a large proportion of medical resource and constituted a big burden of national insurance. Due to complex multi-discipline treatments, poor adherence is frequently encountered. A recently review article reported that mean nonadherence rates of 67% of the included studies about hemodialysis (HD) patients (1), moreover, nonadherence had been reported to correlate with poor outcome in diabetic and hemodialysis patient (2-5). Diabetes is one of the major causes of end-stage renal-disease (ESRD). The proportion of DM amongst all dialysis patients is still growing. The diabetes patients often accompanied with multiple complications and co-morbidities such as hypertension and coronary heart disease. Most of them have suffered from the illness for a long period before the initiation of dialysis therapy. Adherent diabetic patients have better glycemic control and lower mortality rate (6, 7). In addition to usual medication and diet control for dialysis, diabetic ESRD patients need to take more medicine, more diet and lifestyle modification for the glycemic control and other co-morbidities. Furthermore, it goes without saying that the dialysis procedure itself is time-consuming and suffering. Thus, for a diabetes patients undergoing HD, a greater effort will be needed to completely adhere to all instructions from the medical personnel. Sleep disturbance is one of the major complaints of ESRD patients. We had demonstrated significantly higher prevalence of sleep disorder in the uremic patients compared to the general population (8-11). The incidence of sleep disturbances in diabetic patients is substantially higher than in the nondiabetic counterparts (12, 13). Poor sleep quality is independently correlated with poor quality of life and higher mortality in hemodialysis patients (14). There have been a plenty of works assessing the potential etiologic factors of sleep disorders in the uremic patients, including demographic variables, 4 biochemic parameters, co-morbidities, behavioural factors, or psychosocial status (8-11, 15, 16). However, the major etiology of higher prevalence of sleep disorder in uremic patients is still inconclusive. Our recent works had disclosed the significant association between sleep quality and some aspects of psychosocial factors (8, 9) in dialysis patients. To further investigate the issue comprehensively, we designed current study to examine the relationship between nonadherence and quality of sleep in diabetic HD patients. 5 Materials and Methods Subjects The target population for the study was those diabetic patients under regular long-term maintenance hemodialysis at Far Eastern Memorial Hospital. Diabetic patients were defined according previous diagnosis as diabetes, no matter whether antidiabetic agents used or not currently. Patients with documented pyschological disorder, cognitive impairment prohibiting them from completing the questionnaires, dialysis vintage less then 3 months or hospitalization within recent one month were excluded. From January to May, 2009, a total of 76 patients agreed and completed the study. Immediately after informed consent had been obtained, we interviewed them and administered Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and questionnaires about the self-assessment of diet compliance. The adherence to medication was measured by pill counting which was calculated by prescribed dose of phosphate binders divided by the expected amount of consumption in the prior three months(1).We also recorded demographic data, body mass index (BMI), and biochemical parameters within one month of their interview for all individuals. The interdialytic weight gain was calculated by the mid-dialysis weight gain divided by the ideal dry weight. The study protocol had been reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the Far Eastern Memorial Hospital prior to its conduct. Questionnaires Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) for Quality of Sleep Quality of sleep was measured with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (17). This self-administered questionnaire aimed to assess the subjective quality of sleep during the previous one-month period. It comprised 19 self-rated questions that yielded information relating to seven specific patient constructs including subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, 6 sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleep-inducing medication, and level of daytime dysfunction. Each domain was scored according to a scale of from zero to three, the overall questionnaire yielding a global PSQI score of between zero and 21. A higher final score indicated a poor quality of sleep. A total score more than 5 points had been defined as having sleep disturbance in general population (17). This Chinese version of the PSQI has been used previously in Taiwan (18). Questionnaire for diet adherence assessment The questionnaires were designed to measure subject adherence about diet control. There were four descriptions as following: “I eat regularly on time”, “I pay attention to the load of salt intake”, “I eat more than usual at special occasions”, and “I will control the quantity and quality of what I eat”. Each question was answered with “always”, “sometimes”, “seldom”, or “never” and recoded to point 3 to 0, except the 3rd question that was recoded on the contrary. The scores were then aggregated to yield a total score which represented better diet adherence for those higher total scores. Statistical Analysis All values recorded are presented as the median (interquartile range) or proportions. The parameters of interest were analyzed using Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables, chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables, and Spearman rank correlation between scales. All calculations were performed using a standard statistical package (SAS, version 9.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference. 7 Results The average PSQI score was 9.7 ± 4.5. A total of 90.8% patients were classified as poor sleepers (PSQI score>=5). There was no difference in age, gender, co-morbidities (hypertension or coronary artery disease), body mass index, dialysis vintage, or basic biochemical parameters of anemia, nutrition status, osteodystrophy marker and lipid profile between the good and the poor sleepers (Table 1). Those patients dependent on regular use of hypnotics (52.3%) featured even more poor quality of sleep (PSQI scores: 11.1 ± 4.3 vs. 8.1± 4.2, p=0.002). The subjective diet compliance consisted with interdialytic weight gain (r=-0.331, p=0.004) but not medication adherence (r=-0.012, p=0.917). Patients with subjective better diet compliance slept better (r= -0. 287, p=0.013, Figure 1). There was no correlation between medication adherence and quality of sleep (r=-0.039, p=0.740). When comparing those patients with good weight gain control (percentage of interdialytic weight gain<7%) to those with poor control (percentage of interdialytic weight gain≧7%), only diet adherence score differed significantly between these two groups (Table 2). 8 Discussion Our survey confirmed a high prevalence of sleep disorders amongst diabetic hemodialysis patients. Similar to most reports, lack of association between most clinical parameters and quality of sleep was documented. From our results, self reported diet adherence was correlated with quality of sleep, but medication adherence measured by pill counting was not associated with quality of sleep. The nonadherence, measured by skipping or shortening behavior in HD patients, was related to higher morality (3, 5, 19). One study using U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) data reported a 14% increased risk of mortality with skipping one session in a month (20). Another research from a sing urban center involving 295 HD patients demonstrated a 24% increased risk of mortality in patients who shortened dialysis (5). However, the findings are not consistently (2-4, 20), especially for low levels of shortening behavior or when using other surrogate of compliance, such as serum level of phosphate or interdialytic weight gain to represent diet compliance. It is difficult to measure adherence and define a proper cut-off point for nonadherence (1, 3). A study examined factors affecting adherence to medications for patients with co-existing diabetes and CKD showed that they are not convinced of the need, effectiveness and safety of the medications (21). Besides, many factors, stronger than adherence itself, would influence the serum phosphate or potassium levels, such as medication prescribed or residual renal function. These may explain the discrepancy between diet adherence, medication adherence and other surrogate markers of adherence. There is currently no solid evidence or conclusive consensus about the cut-off point of adeuqte interdialytic weight gain. The intersession weight gain is related to the residual renal 9 function, nutritional status, physical activity, weather and adherence. Here we used 7% as cut-off point according to the guideline of standardized operative procedure in our dialysis center, which is the cut-off point that deserved further individualized evaluation and education. The illegitimate skipping or shortening behavior is rare in our dialysis center, probably because of the selection process of patients who choose to stay in medical center for long-term HD. Thus we measured compliance according to patient’s own assessment on diet control and pill counting. The subjective assessment of diet adherence consisted with percentage of interdialytic weight gain, but the correlation between medication adherence with either diet adherence or interdialytic weight gain is poor. Both diet and medication adherence did not correlate with serum phosphate level or potassium level. Nonadherence was reported to associate with many psychosocial factors, such as younger age, poor socioeconomic background, and lack of family support (22). One meta-analysis demonstrated a significant association between depression and nonadherence in diabetes patients(23). Phillips KD et al. conducted a study to examine the relationships among sleep disturbance, depressive symptoms and adherence to medications among 173 HIV infected women (24). They found that women who reported greater sleep disturbance also reported a higher level of depressive symptoms and poor adherence. Similarly, it is likely that depressed diabetic HD patients have more trouble in sleep and have less desire to follow the instructions from the medical personnel. There may be many other common factors underlying both sleep disturbance and nonadherence. We have reported several social factors, including marital status and education levels, correlated significantly to quality of sleep in dialysis patients(8, 9). Those patients with sleep disturbance and non-adherence may share the same social factors, such as low socioeconomic background or poor family support. Besides, those adheres to diet control would tend to have more positive attitude toward their condition and stronger belief in 10 treatment benefit, thus their quality of sleep was less effected by the disease. Furthermore, it is likely that patients with higher diet adherence would take less stimulating foods or beverages to avoid interfering their sleep quality. In the other way, the complications of diabetes, renal failure and dialysis, such as restless leg syndrome, may impair the quality of sleep and attenuate the patients’ faith in the medical personnel, which then resulted in nonadherence. Since most biochemical parameters did not associate with quality of sleep or markers of adherence, it is difficult to deal with the issues from a biologic viewpoint. There were several limitations in our survey. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study. So we could demonstrate only the association rather than cause-and-effect relationship between adherence and quality of sleep. Secondly, the studied subjects all came from one single medical center in northern Taiwan. The potential selection bias will limit the generalization of our results to all diabetic HD patients. Besides, the relative small sample size of this survey may hold insufficient statistic power to detect true difference. Especially the case numbers of good sleepers or patients with poor weight gain control were too small to fit parametric analysis. Finally, the diet adherence questionnaire we used is neither standardized nor universal. The reliability and validity may be questionable. In conclusion, both nonadherence and sleep disturbance in diabetic HD patients are popular and challenging issues for medical personnel. As best we are aware, this is the first study to demonstrate that diet adherence is significantly correlated with quality of sleep in dialysis patients. The correlation between subjective qualities of sleep and diet adherence amongst diabetic HD patients merits further research to explore potentially modifiable common factors. 11 References 1. Schmid H, Hartmann B, Schiffl H. Adherence to prescribed oral medication in adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a critical review of the literature. European journal of medical research 2009; 14: 185-190. 2. Kimmel PL, Varela MP, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Interdialytic weight gain and survival in hemodialysis patients: effects of duration of ESRD and diabetes mellitus. Kidney international 2000; 57: 1141-1151. 3. Leggat JE, Jr. Adherence with dialysis: a focus on mortality risk. Seminars in dialysis 2005; 18: 137-141. 4. Leggat JE, Jr., Orzol SM, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Golper TA, et al. Noncompliance in hemodialysis: predictors and survival analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1998; 32: 139-145. 5. Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, Simmens SJ, et al. Psychosocial factors, behavioral compliance and survival in urban hemodialysis patients. Kidney international 1998; 54: 245-254. 6. Rhee MK, Slocum W, Ziemer DC, Culler SD, et al. Patient adherence improves glycemic control. The Diabetes educator 2005; 31: 240-250. 7. Rombaux P, Bertrand B, Boudewyns A, Deron P, et al. Standard ENT clinical evaluation of the sleep-disordered breathing patient; a consensus report. Acta oto-rhino-laryngologica Belgica 2002; 56: 127-137. 8. Yang JY, Huang JW, Peng YS, Chiang SS, et al. Quality of sleep and psychosocial factors for patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2007; 27: 675-680. 9. Yang JY, Huang JW, Kao TW, Peng YS, et al. Impact of spiritual and religious activity on quality of sleep in hemodialysis patients. Blood purification 2008; 26: 221-225. 10. Yang JY, Huang JW, Chiang CK, Pan CC, et al. Higher plasma interleukin-18 levels associated with poor quality of sleep in peritoneal dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007; 22: 3606-3609. 11. Pai MF, Hsu SP, Yang SY, Ho TI, et al. Sleep disturbance in chronic hemodialysis patients: the impact of depression and anemia. Renal failure 2007; 29: 673-677. 12. Han SY, Yoon JW, Jo SK, Shin JH, et al. Insomnia in diabetic hemodialysis patients. Prevalence and risk factors by a multicenter study. Nephron 2002; 92: 127-132. 13. Ho PM, Magid DJ, Masoudi FA, McClure DL, et al. Adherence to cardioprotective medications and mortality among patients with diabetes and ischemic heart disease. BMC cardiovascular disorders 2006; 6: 48. 14. Elder SJ, Pisoni RL, Akizawa T, Fissell R, et al. Sleep quality predicts quality of 12 life and mortality risk in haemodialysis patients: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23: 998-1004. 15. Bornivelli C, Alivanis P, Giannikouris I, Arvanitis A, et al. Relation between insomnia mood disorders and clinical and biochemical parameters in patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis. Journal of nephrology 2008; 21 Suppl 13: S78-83. 16. Gusbeth-Tatomir P, Boisteanu D, Seica A, Buga C, et al. Sleep disorders: a systematic review of an emerging major clinical issue in renal patients. International urology and nephrology 2007; 39: 1217-1226. 17. Smyth C. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). J Gerontol Nurs 1999; 25: 10-11. 18. Mei-Sau Hui J-WH, Kuan-Yu Hung, Yue-Joe Lee,, Ming-Shiou Wu K-DW, Tun-Jun Tsai. Sleep disorders and hypertriglyceridemia in peritoneal dialysis patients. Acta Nephroogica 2002; 16: 114-118. 19. Saran R, Bragg-Gresham JL, Rayner HC, Goodkin DA, et al. Nonadherence in hemodialysis: associations with mortality, hospitalization, and practice patterns in the DOPPS. Kidney international 2003; 64: 254-262. 20. O'Brien ME. Compliance behavior and long-term maintenance dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1990; 15: 209-214. 21. Williams AF, Manias E, Walker R. Adherence to multiple, prescribed medications in diabetic kidney disease: A qualitative study of consumers' and health professionals' perspectives. International journal of nursing studies 2008; 45: 1742-1756. 22. Loghman-Adham M. Medication noncompliance in patients with chronic disease: issues in dialysis and renal transplantation. The American journal of managed care 2003; 9: 155-171. 23. Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes care 2008; 31: 2398-2403. 24. Phillips KD, Moneyham L, Murdaugh C, Boyd MR, et al. Sleep disturbance and depression as barriers to adherence. Clinical nursing research 2005; 14: 273-293. 13 Tables and Figures Table 1 Summary of the demographic data (PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; TG: triglyceride; TCHO: total cholesterol) Patient number Age (years) Males/females Body mass index (Kg/m2) Dialysis vintage (months) Hypertension Coronary artery disease Hct (%) CRP(mg/dl) Albumin (g/dL) Ca(mg/dL) P(mg/dL) K(mEq/L) TG(mg/dL) TCHO(mg/dL) HbA1c(%) total 76 61.8(54.1-66.8) 42/34 24.2(21.6-26.8) PSQI < 5 7 (9.2%) 58.5(51.0-66.9) 5/2 23.9(20.6-24.9) PSQI ≧ 5 69 (90.8%) 61.8(54.8-66.8) 37/32 24.7(21.7-26.8) 40.0(19.2-57.5) 18.1(9.2-39.3) 38.1(23.6-59.6) 0.066 57(75%) 16(21.1%) 6(85.7%) 1(14.3%) 51(73.9%) 15(21.7%) 0.673 1.000 35.1(32.3-37.7) 0.35(0.13-0.90) 4.2(3.9-4.3) 9.2(8.8-9.7) 5.0(3.9-6.2) 4.6(4.5-5.1) 146(96-218) 174(152-204) 7.2(6.3-8.4) 35.7(34.6-40.6) 0.13(0.07-0.47) 4.2(4.1-4.5) 8.9(8.4-9.5) 5.0(4.2-7.8) 5.2(4.6-5.4) 132(85-269) 191.5(179-205) 6.5(6.2-7.0) 35.1(32.1-37.3) 0.38(0.15-1.04) 4.2(3.9-4.3) 9.3(8.9-9.7) 4.9(3.9-6.2) 4.6(4.4-5.1) 146(96-217) 170(150-203) 7.3(6.4-8.4) 0.388 0.194 0.390 0.250 0.562 0.132 0.943 0.223 0.165 P value 0.520 0.450 0.461 Note: Data was presented as median (interquartile range) or as number(percentages). 14 Table 2 Difference between high interdialytic weight gain (≧7%) and low interdialytic weight gain (<7%) (IDWG: percentage of interdialytic weight gain; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; TG: triglyceride; TCHO: total cholesterol) Patient number Age (years) Males/females Body mass index (Kg/m2) Dialysis vintage (months) Hypertension Coronary artery disease Hct (%) CRP(mg/dl) Albumin (g/dL) P(mg/dL) K(mEq/L) TG(mg/dL) TCHO(mg/dL) HbA1c(%) Diet adherence score Medicine adherence PSQI IDWG < 7% 66 (89.5%) 62.4(54.8-68.1) 37/29 24.7(21.7-26.8) IDWG ≧ 7% 8 (10.5%) 56.6(51.9-60.5) 5/3 23.2(20.0-24.8) 38.7(18.7-59.3) 31.0(17.7-55.0) 0.658 51(77.3%) 14(21.2%) 5(62.5%) 2(25.0%) 0.393 1.000 35.1(32.5-37.8) 0.34(0.14-0.79) 4.2(3.9-4.4) 5.0(4.1-6.3) 4.6(4.5-5.1) 142(96-217) 171(153-204.5) 7.1(6.2-8.3) 8(7-9) 0.94(0.74-1.0) 10(6-13) 35.7(31.1-37.8) 0.30(0.13-1.80) 4.3(4.2-4.3) 4.3(3.7-5.5) 4.8(4.5-5.2) 148(112.5-251) 190(175-202.5) 7.4(6.5-10.6) 7(4.5-7) 0.94(0.56-1.0) 12(7.5-15) P value 0.097 1.000 0.200 0.865 0.905 0.578 0.189 0.872 0.672 0.487 0.299 0.006* 0.510 0.410 Note: Data was presented as median (interquartile range) or as number(percentages). 15 Figure 1 Significantly negative correlation between Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and scores of self-assessed diet compliance r=-0.284 p=0.013 14 12 diet adherence 10 8 6 4 2 0 0 5 10 15 20 PSQI score 16