Origins of the Liberal Reform

advertisement

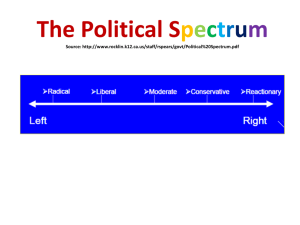

Internal Reasons for the Liberal Reforms The Liberals won the 1906 General Election with a large majority over the Conservatives. The election had been fought on the issues of tariff reform, championed by Joseph Chamberlain and adopted by the Conservatives. The Liberals had stood in defence of Free Trade with a commitment to limited social reform, although many Liberals still supported the idea of individualism, and to a lesser extent, laissez faire. Therefore social reform was not a major issue in the 1906 election. Overview Liberal motives for introducing the reforms were mixed. There was an element of compassion: some Liberals felt that it was simply not right for a third of the population to be living in such misery. However, if this had been the only consideration it is doubtful if much would have been done. In fact the government had no bills prepared and no programme of social reform drawn up. Probably more significant was the need for a healthy working class for military and economic purposes. If Britain was to be involved in a major war, an efficient army would be needed to defend the Empire. The Birmingham Chamber of Commerce called for a health insurance and old age pensions on the grounds that a healthy work force would be more efficient and more profitable. Some reform therefore was necessary for national survival. The Liberals were under pressure from the Labour Party and from the trade unions, and there was the added incentive that a limited amount of social reform would attract voters away from socialism and the new Labour Party. There was the need to show that Liberals had policies which clearly distinguished them from the Conservatives, so the working class would not drift towards them. Finally, there were the political ambitions of Lloyd George and Churchill, both of whom were anxious to enhance their reputations. Each reform was a response to a particular problem or situation. There was no master plan to set up a ‘welfare state’. Ever since the Liberal’s implemented social reform 1906-1914, historians have been divided as to why such reform occurred. Historiography Source: J.R. Ray, The Origins of the Liberal Welfare Reform 1906 -1914 In the history of social reform in Britain, the years between 1906 and 1914 stand out as one of the periods of major reform. Ever since, historians have been trying to explain why there should have been such a concentrated burst of activity by the Liberal governments of those years. The origins of social reforms are always complex. Few of the reforms of the period from 1906 to 1914 can be regarded as the outcome of a single set of influences. Not surprisingly explanations of the origins of the Liberal social reforms have been diverse. Foreign influences were extremely important in the origin of these reforms. Historians usually cite Lloyd George’s famous journey to Germany in 1908, out of which came his ideas for national insurance. Social historians have stressed the importance of the Boer War in the origin of the Liberal reforms. Many historians have argued that the social welfare reforms were the inevitable result of the extension of political democracy in the nineteenth century. There is a wide measure of agreement among historians that political pressure from the working class was one of the main reasons for the origins of the Liberal reforms. Politicians introduced social reform either to attract electoral popularity or to prevent workers turning to extreme socialist solutions. Both the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress had extensive social reform programmes by the early 1900s, including free education for all; old age pensions; the abolition of the Poor Law; and measures to deal with unemployment. The Labour Party also wanted a comprehensive health service. It is implausible to assert that the social reform of the period from 1906 to 1914 was simply the inevitable result of working-class pressure, through the ballot-box, or by direct action or the threat of it. This does not mean that such pressures were not important, or non-existent, as some historians have tended to suggest. Changing Attitudes to Laissez Faire During the late 19th century, the British government acted according to the principles of Laissez Faire. Individuals were solely responsible for their own lives and welfare. The government did not accept responsibility for the poverty and hardship that existed among its citizens. A popular point of view at the time was that poverty was caused by idleness, drunkenness and other such moral weaknesses on the part of the working classes. The poor were seen by the wealthy as an unfortunate but inevitable part of society. The state’s only tasks were maintain law and order, defend the country and provide a level playing field for competition. The only help available came from the Poor Law or charities. The Poor Law had been set up in 1834 at a time when Britain was a rural society. By the end of the century it was unable to cope and was hated. By the 1900s the workhouses housed the elderly, the sick, the frail and the orphaned: few able people went there. Indeed 90% of the unemployed never touched poor relief despite living in desperate circumstances. Charles Booth commented on workhouses in 1895 ‘Aversion to the ‘’House’’ is absolutely universal and almost any amount of suffering and privation will be endured by the people rather than go to it’. Moreover the evidence pointed to a problem that was beyond the ability of charities to solve alone. Even Octavia Hill admitted that the housing that philanthropists had worked so hard to build over the previous thirty years provided homes for only 26,000 people. London’s population rose by that number in six months. Social investigations of Booth and Rowntree In the latter years of the 19th century, there had been a growing interest in the poor, poverty and the cost of supporting paupers. Investigative journalists, like Henry Mayhew (1812 – 87) who wrote a series of articles for The Morning Chronicle, alerted the reading public to the plight of the poor. However the government assumed that Mayhew had only stumbled on a few of the worst individual cases and that most of society was content with their lot. There were many local surveys of the needs of the poor, and Christian groups like The Salvation Army began bringing practical help to the needy and outcast but again the government was content to leave problem alone. At the end of the nineteenth century two middle class social explorers, Charles Booth and the Quaker social reformer Seebohm Rowntree, independently highlighted unprecedented levels of poverty in different parts of England by using more quantitative, scientific methods. One of the most famous investigations into poverty was carried out by Charles Booth. He was a wealthy ship owner who moved his offices to London. He refused to believe official statistics that 25% of working people were living in poverty. He conducted extensive research in London and presented his findings as hard, statistical facts rather than anecdotal opinions. His sources of information came from the Census, School Board attendance officers’ reports interviews with Poor Law Boards of Guardians, teachers, police, sanitary inspectors, trade union officials, charity workers and clergy. He was assisted by a talented team including Beatrice Webb. He showed that poverty had causes often beyond the control of the poor themselves. These causes included low pay, unemployment, sickness and old age. From Booth’s investigation of the social conditions in London he published The Life and Labour of the People of London, which appeared 1889 – 1903. From a survey of 4,000 people, he found that 30.7% of the East London population were living below what Booth called a ‘poverty line’ which meant that the family income was insufficient to meet basic needs such as food, rent and clothing. He also found that 85% of those living in poverty were poor because of problems relating to employment; unemployment, short time working or low wages. These findings were amplified by Seebohm Rowntree who was the son of the chocolate magnate, Joseph Rowntree. His study of conditions in York which found that 28% of the people of York were living in some degree of poverty, either what he called ‘primary’ poverty when a family income fell below the 21 shillings required to maintain ‘spartan physical efficiency’, or ‘secondary’ poverty, where spending took the residual income below the poverty line. He also showed that in York wages were so low that even men in full time employment were forced to live close to starvation level. He made careful use of recent scientific work to establish what a family needed to earn to buy adequate food and fuel and to pay the rent. He concluded that 52 per cent of the very poor were paid wages too low to sustain an adequate life. Around 21 per cent of families lived in misery because the chief wage earner had died, or was too ill or too old to work. As a result of this people realised that if York, a relatively small English city, had such problems then so would other British cities and that the problem of poverty was therefore a national one. Rowntree stated that ’we are faced with the startling possibility that from 25 to 30 per cent of the town populations of the United Kingdom are living in poverty’. The importance of the findings by Booth and Rowntree as a motive for social reform was that they exploded the myth that poverty was due only to personal inadequacies and character defect, but attributed to low levels of wages, the uncertainty or irregularity of employment, and from the ravages of sickness, infirmity and old age. This evidence was widely publicised and read and Booth became an advocate of government action, such as the introduction of pensions for all. Their findings agreed on two key points. Up to 30% of the population of the cities were living in or below the poverty level and that these conditions were such that they could not pull themselves out of poverty by their own actions alone. They also both identified the main causes as being illness, unemployment and age, both the very young and the old. The Royal Commission on the Poor Laws was set up by the Conservative government in 1905. It was to enquire into the working of the Poor Laws and to advise the government on the best ways of relieving the poor. The commission consisted of people with a wide range of appropriate expertise: poor law guardians, members of charitable organisations, religious and trade union leaders as well as Charles Booth and Beatrice Webb. The commission made thousands of visits and collected nearly 500 volumes of evidence. But, when they came to write their final report and make recommendations to the government, they couldn’t agree, so they wrote two reports. The majority report recommended no change, which suited the government. However the commission had collected a vast amount of evidence and had given poverty a higher profile. The social investigations of Booth and Rowntree, accompanied by a whole range of novels in the ‘Darkest England’ mould, saw people’s awareness greatly enhanced. The extent of poverty became more evident when compared with the excesses of the rich during the Edwardian era. While the vast numbers of poor were struggling to make ends meet, the rich could expect a totally different life style. They did not work for a living, they lived in large mansions situated in the countryside; they were tended by domestic servants and they lived a life of leisure, attending all the major sporting and social events. They spent their holidays fishing or shooting in Scotland and wintered abroad, often in the south of France. The gulf between the lifestyles of the rich and poor was huge. The development of the popular press, the growth of education and the increasing strength of working class movements helped to publicise the contrast between poverty and ostentatious wealth in Edwardian society. The Liberal M.P. and economist, Chiozza Money, estimated that one and a quarter million people owned almost half the wealth of the country, while 38 million people held the other half. Such inequality led to demands for some sort of redistribution of wealth. Threat of the Labour Party The Liberal Government was worried on the political level as well. By 1900 most working men had the vote so workers now had some political power and would obviously vote for the party which promised to improve their conditions. Up till the 1880’s there was only middle class Liberal and Conservative parties for working men to vote for and the Liberals wanted to attract those votes. From 1900 the Labour Party was founded to represent the working classes in parliament and they were competing for the same votes. If the Liberals were seen as unsympathetic to the poor, what might happen at elections in the future? It was therefore to the political advantage of the Liberal government to offer social reform, even if some of them did not fully believe in the principle of government intervention. In 1892 there was only 1 Independent Labour MP, by 1900 this had doubled but by 1906 there were 29 Labour MPs elected to Parliament. Many Liberals felt that Labour had the potential to replace them as the main alternative to the Conservatives. A Liberal programme of social reform could out-trump Labour and stop the working class defecting to them. Although the Labour Party was numerically insignificant in the context of Liberal euphoria in 1906, it did give cause for concern as the growth of Labour showed that the working man felt that they needed special sectional representation within the political system. The 1906 election provided the Liberals with the chance to show that they were a party of concern and conscience which could legislate in the interest of the poor and that there was no need for a party designated to this one sole interest group in society. The threat of Labour as a motive for reform in the early period of Government is unimportant. However, the growing threat of Labour began to be felt from 1909 onwards due to high unemployment caused by Britain entering a recession. This led to great discontent among the masses, which is clear from the bad run of by-election results in 1907 and 1908, with Conservatives and Labour winning seats. A threat was therefore clear to those politically astute politicians such as Lloyd George and it is no coincidence that with growing discontent due to unemployment from the working class and the gain of seats in by-elections by Labour that the most revolutionary Liberal reforms occurred shortly before the 1910 election and after. The most important pre-election legislation was Winston Churchill’s Labour Exchange Act, and Lloyd George’s famous, ‘Peoples Budget’ of 1909 which taxed the rich for the poor. One of the reasons Lloyd George and Winston Churchill pushed for limited state intervention was to draw support away from the Labour Party. Indeed, Lloyd George spoke on the threat from the Labour Party. I can tell Liberals what will make this Labour Party a great force in this country – a force which will sweep away Liberalism amongst other things. If it were found that a Liberal Parliament had done nothing to cope seriously with the social condition of the people to remove the national shame of the slums and widespread poverty in a land glittering with wealth. Many historians see the Liberal social reforms as a response to the growth of Socialism at the start of the twentieth century. There was a deep concern that a more radical brand of socialism, committed to the destruction of the capitalist system, might arise if action was not taken to improve conditions for the working class. Many Liberals hoped that a system that gave people a degree of social and economic independence would be an insurance and antidote against the spread of socialism. Therefore it is fair to say that the fear of socialism did play an important part in causing the Liberal reforms. New Liberalism It would be far too harsh to argue that the Liberals passed social reforms just to win votes. A new generation of Liberal politicians genuinely believed that the government had a responsibility to help the poor and to remove the stigma attached to the 1834 Poor Law, as this law only offered a solution to destitution, not to poverty. New Liberals believed that the state should be prepared to intervene to help the worst off in society so that they could make individual decisions about their own lives and gain some level of individual liberty. It should also be noted that there was a feeling of genuine philanthropy in many of the new Liberals who felt that it was ‘the right thing to do’ to help the most vulnerable members of society. Some New Liberal MPs, such as David Lloyd George had risen from the working class and knew the conditions first hand. They had rethought a lot of the basic principle and strategies of liberalism. This ‘New Liberalism’ had been greatly influenced by the philosopher T.H. Green and the writer J.A Hobson. Under their guidance, a new approach was drawn up by radical Liberals and presented to the party as the way forward. The New Liberals argued that, in the past, Liberals had been too concerned with individual liberty. People did not want excessive Government interference in their lives and poverty was the fault of the individual, therefore Government should not get involved. The surveys showed that this was not necessarily true. New Liberals argued that the state had to intervene to help the most vulnerable in society because to live in poverty, hardship and uncertainty meant they were denied the individual liberty should be prepared to intervene to help the most vulnerable in society because to live in such grinding poverty, hardship and uncertainty meant that they were denied individual liberty to make life changing decisions. This had led them to ignore the needs of those who lived and worked in such appalling conditions. This became in practice a change in attitude towards the state and how it should operate in relation to its citizens. Old Liberals felt that helping people would take away their independence and give them no incentive to help themselves while New Liberals said that helping the poorest members of society would give them independence. Finally, old Liberals thought that taxes should be as low as possible to allow people to spend their money as they wished while New Liberals felt that taxes needed to be raised to pay for welfare schemes to help the vulnerable. However, there was not an enormous split between Old and New Liberals, and the New Liberals were themselves anxious to distance themselves from socialists in order to maintain their appeal to the wider Liberal electorate. Along with Old Liberals they agreed on the importance of the individual and individual initiatives, they both wanted social services to be funded by voluntary contributions, they both distinguished between the ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor and they both believed in the idea of self improvement. Their personal motives to relieve poverty cannot be disregarded in explaining the burst of reform from the Liberals 1906 – 1914. Without a change in thinking, reform would not have played such a major role in Liberal Policy, as the old doctrine of self-help would still have been the bedrock for Social Policy. However, the emergence of these new charismatic politicians who realised the inadequacies of a non-interventionist state and the problems that poverty brought to society meant that they could make a difference in the direction of Government Social Policy. Therefore, with opinion swaying towards state intervention and the emergence of the Labour party who were seen as the party of the working class, a change in the direction and ideology of Liberal Policy had to be implemented. This change in direction in Liberal thinking had begun at the beginning of the twentieth century and came to be called ‘New Liberalism’. This left wing ‘New Liberal’ group broke away from traditional Gladstonian ideology and included some of the most important politicians in twentieth century history such as, Asquith, Lloyd George and Winston Churchill. The “old Liberal” Prime Minister Campbell Bannerman died and was replaced by Asquith in 1908. New Liberals with new “interventionist” ideas such as David Lloyd-George and Winston Churchill were given important government jobs in charge of the financial departments. These appointments are one of the main reasons why so many reforms happened from 1908 onwards. Without the emergence of such an intellectual revolution in Britain it would have been very unlikely that Britain by the outbreak of World War 1 in 1914 would have had social policy implemented that helped create a more efficient nation for the onslaught of war. Municipal Socialism Although the Liberal Party had been out of power at a national level for some time, they still controlled many local councils. Many of these councils had to deal with poverty on their own doorstep and set up systems to help their people. This became a model which could be used at a national level. Birmingham was an example. Joseph Chamberlain, the mayor, took control of social services and utilities to ensure that conditions throughout the city improved for everyone. Glasgow controlled the water supply and street lighting. These moves were paid for by the rates, so richer people were subsidising poorer people; a shift from Laissez Faire policy. Increasingly ideas such as these became called Municipal Socialism and were seen as a template for national action.