Ice Cube Inquiry

advertisement

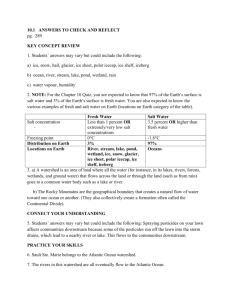

Dehesa Charter School Experiment of the Month Ice Cube Inquiry Introduction: In this activity students begin by observing ice as it melts in a glass. They are then asked to formulate and test hypotheses as they conduct an experiment of their own design. Through ongoing discussion during the activity they are challenged to make sense of what they observed and to explain the phenomena. This type of investigation or inquiry develops communication, problem-solving and reasoning skills and encourages students to consciously observe the natural world in a new way. These skills form a foundation for innovative and creative scientific thinking. CA Content Standard K-12: Scientific progress is made by asking meaningful questions and conducting careful investigations Materials 2 tall, clear glasses 1 teaspoon Water (room temperature) 1 straw Salt (NaCl) 2 ice cubes (same size) Procedure: Parent Demonstration: Allow your child to observe the materials. As your child watches, fill each glass about 90% with room-temperature water. Put one rounded teaspoon of salt into the first glass and stir until the salt has dissolved. Slowly blow three long breaths (CO2) through a straw into the first glass and then remove the straw. Add one ice cube to each glass and ask ‘What do you see happening?’ Your child will observe that the ice cube in the plain water melts more quickly than the ice cube in the glass of water with salt and CO2. They may be surprised and comment, “But I thought salt was used in winter to melt ice!” Engage in a conversation where you discuss their observations of the phenomena and common knowledge about ice, salt, CO2 etc. 1. (This can be done the following day) Ask your child to draw the two setups, describe in writing what was done with the materials, and record the results of each setup. A discussion of the demonstration and a reminder to include everything they saw may be needed. Parent: have your child use the student worksheet if desired. 2. Prompt your child to identify the variables and constants of the demonstration: ask, ‘What things were different about the two setups? [these are the variables] Then ask, ‘What things were the same about the two setups?’ [these are the constants] Discuss and list the differences (variables) between the two setups and the similarities (constants). Parent: variables are carbon dioxide, salt; constants are water temperature, size of ice cubes. 3. Form a Hypothesis: Next your child should develop a hypothesis for each variable (#1: carbon dioxide; #2: salt). Hypotheses are written in an ‘if…then’ format. Use the following template for each hypothesis: If ____________ is the important variable, then changing _____________ will affect __________. Your child fills in the blanks to develop a hypothesis for each variable (e.g. ‘If carbon dioxide is the important variable, then changing whether carbon dioxide is used will affect how quickly the ice cube melts’) Parent: consult the student sample pages for other examples of hypotheses 4. Design an Experiment: For each hypothesis, your child will design an experiment with two setups. For a fair test, change only the variable being tested (carbon dioxide or salt). The original constants (water temperature and ice cube size) and any other variables remain the same for both setups. This methodology will prevent other variables from affecting the outcome. Parent: for example, one could design an experiment to test the CO2 hypothesis using salt in both setups. Or an alternative experiment to test the CO2 hypothesis could not use salt at all. Both are fair tests of the CO2 hypothesis because carbon dioxide is the only independent variable changing. 5. Make a Prediction: Before your child does their experiment, they make a prediction about what will happen in each experiment, based on the original demonstration. Their prediction should only focus on the variable they are testing (carbon dioxide or salt). Parent: your child will know when they have identified the important variable (the one responsible for the ice cube melting at a different rate) when the results from their experiment match the outcome of the parent demonstration. Consult the student sample pages for examples of predictions. 6. Conduct your Experiment: Decide what materials you need and have your student worksheet or science notebook ready. Complete your experiment as designed and record the results for each setup. Compare your results with your prediction. If your results don’t match your prediction then the important variable hasn’t been identified. If your child identifies the important variable in their first experiment they should still conduct all the experiments to support their conclusions. 7. Discuss your Findings: Review the results of the all the experiments with your child. Your child may then summarize their conclusions and explain the scientific phenomena in a few paragraphs, a labeled illustration or an oral report. Parent: the important variable for this demonstration is salt. Salt keeps the ice cube from melting quickly. The carbon dioxide blown into the water has no effect on melting rate. As the ice cube in the plain water melts, the cold water around it becomes heavier (denser) than the rest of the water in the glass. The cold water sinks and pushes up warmer water from the bottom, which melts the ice cube more and continues the cycle. This circular movement of water is called convection current. Adding salt makes water even denser than cold water. As the ice cube in the salt water begins to melt, the denser salt water keeps the cold water around the ice cube from sinking. The ice cube melts at a much slower rate because no convection current is set in motion to bring warmer water up from the bottom. Taking It Further 1. To show the actual convection current or lack of current, create colored ice cubes using enough food coloring in the water to make the water nearly opaque. Re-create the original setups, substituting the colored ice cubes for the original clear ones. The convection currents in the glass with plain water will become clearly visible as the colored ice cube melts and the denser, cold, colored water sinks to the bottom. In the glass with salt water, the melting ice cube will form a layer of cold, colored water that stays on the surface. No convection currents are formed because the salt water is denser than the cold, colored water. 2. Research weather events, such as lake effects and sea breezes. Explain how these events are based on convection currents. 3. Using internet and library resources research convection currents. Explain how convection currents work in the ocean (like the Arctic) and how these currents affect sea life and earth’s climate.