PORT_P1

advertisement

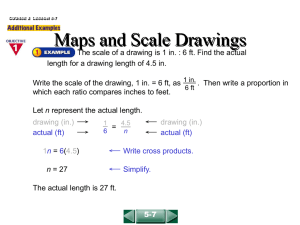

A Quantitative Assessment of Freehand Drawing and Some Suggestions for Its Improvement as a Rock Art Recording Method By John M. Brayer, ..., Henry Walt, ... and Bruno David, ... I. INTRODUCTION This paper attempts to improve the quantitative understanding of one of the most commonly used types of rock art recording, freehand drawing. Although this method is very commonly used, its properties are not very well understood and have not been studied quantitatively. This is a first attempt to assess and control the objective sources of error in rock art recording by freehand drawing. We compare the results of many persons attempting to record the same panels, and attempt to derive quantitative measures of their geometric and content inaccuracies. We conclude with some suggestions that might be used to minimize these errors. Image recording can be divided into manual and automated methods, depending on whether or not an image sensor is used. Manual techniques include drawing, tracing, computer-aided drawing, rubbing and casting. Automated techniques us some form of sensor, scanner or machine to capture the entire image. The most frequently employed automated technique is photography. Some of the criteria used to evaluate these technologies include image completeness, accuracy and efficiency. By image completeness, we mean recording all properties of the object even when the glyph is very faint or difficult to decipher. Drawing has been one of the preferred rock art recording techniques for many years. It has the advantage of being inexpensive and requiring little extra equipment. It also allows the recorder to use his/her interpretation to fill in details that are very faint in the original. This, of course, presents both positive and negative problems and consequences. That is, the subjectivity of interpretive conventions can become a serious disadvantage. Faintness and superposition are common problems in rock art that are perhaps best overcome by drawing and tracing techniques. Sketching or drafting is likely to be inaccurate if methods are not tightly regulated. Drawing also has the disadvantage of requiring substantially more time and skill by the recorder than does photography. Drawing is faster than tracing but less accurate. Sketches or drawings have another advantage over tracings in that they avoid rock contact. To be of use, drawings must be rendered to scale and incorporate a consistent set of visual conventions such as the use of solid lines, dashed lines, stippling and cross-hatching. Since drawing is most useful for marginal glyphs, it is important to check sketches and rock surfaces under various lighting conditions. A drawing can be one of 3 types, each successively more time consuming: a field sketch, a ruled drawing and a grid drawing. rendered unaided. A sketch is A ruled drawing uses a flexible ruler to measure key features and is done on graph paper. A grid drawing makes use of a string grid over the original to produce accurate scale and composition. We report here on the first steps we are taking in a process to quantify and improve on free-hand drawing as a recording method. began with 2 basic hypotheses. The study reported here The first hypothesis is that general untrained recorders do not do a very good job of recording, especially when the subject is indistinct and relatively inaccessible. recording is two-fold. general geometry right. We believe that the purpose of First, it is important for the recorder to get the Secondly, the recorder should be very careful not to miss any of the details and should pay particular attention to indistinct areas. We think that in general, recorders spend too much time concentrating on the difficult job of getting the geometry right and often neglect the task of studying the details and the indistinct areas. This leads us to our second hypothesis that recorders will do much better if given a copy of a photographic image on a piece of paper on which they can make various corrections, additions and annotations. In this way, they are already starting with the correct geometry and can concentrate their whole attention on details and indistinct areas, with the distinct areas already well recorded on the photograph. We further believe that such a recording method will be invaluable to scholars studying the materials later, away from the site, because they have both the photo and the annotated drawing for comparison. And they photo and the drawing are rendered in the same geometry. (circular target with perpendic is better) b) People do better getting geometry right and also better on details if they start with a photo. (comp-aided photo/print plots a big help) II. PREVIOUS STUDIES III. SELECTION OF ORIGINAL SITES AND DRAWINGS The field drawings selected here in this first stage of the study were selected primarily for the convenience reasons. While we would normally select a more distinctly defined set of glyphs for such a study as this, in this case these were the glyphs available when the 18 people were available to do the drawing. The glyphs represent a wide range of distinguishability, they represent no figure that is easily recognizable and they are in a position in a rock shelter that is relatively inaccessible. IV. PHOTOGRAPHS Photographs of each panel were taken to the best of our ability. These photos were not as good as we would have liked, but they were the best that could be obtained, given the relative inaccessibility of the panel in the rock shelter. V. DRAWINGS AND DRAWERS Who were the drawers. VI. DIGITIZATION The photographic and freehand drawings from the study were digitized on a flatbed scanner. The photographic images were stored in the computer in JPEG format and the drawings were stored in GIF format. Both types of images were displayed using an image processing program (Adobe Photoshop) so that the pixel coordinates of key “control points” in the images could be recorded. A control point is an easily identified reference mark of some kind in the image. We wish to find these marks in all of the drawings and photographs and check both that they are present and that their relative geometries are consistent. VII. GEOMETRIC MAPPING All of the drawings and photos can be mapped by a planar mapping onto a consistent geometric plane. This process is similar to the “morphing” technology used widely in graphics and image processing. Here the process is rigidly controlled and produces quantitative data which can be used to assess the drawings. As an image is mapped, each point at position, (x,y) in the original image is mapped to a new position, (x’,y’) in the new image according to the mapping: x’ = a*x + b*y + c + Ex y’ = d*x + e*y + f + Ey The coefficients, a, b, c, d, e, and f, define the mapping from the old image (x,y) to the new image (x’,y’) and are derived from the control points. Basically they specify how the image plane is tilted when we are viewing it. The Ex and Ey factors represent the errors in the mapping and these can be used as a quantitative measure of the quality and consistency of the geometry of the recordings. From the control points we can derive the mean squared values of these errors. Finally, once the images have been mapped onto a consistent geometry, we can measure the percentage of the areas of the features of the image that overlap. In a reasonable sense, these percentages represent the agreement in the content of the drawings and can be used as another quantitative measure of the recording quality. VIII. MEANING OF THE COEFFICIENTS IX. RESULTS X. SUGGESTIONS In addition to normal drawing, with modern digital equipment in the field, it is possible to use guided drawing. This concept begins with a digital photograph taken by a digital camera. This photograph is then transferred to a printer, either directly that is then printed lightly on paper. This printout can be accomplished in the field with a digital camera, a laptop and a portable printer. The recorder can then return to the petroglyph and compare the printed image to the original glyph, making sketches of added areas or deleted areas in addition to other notations. Both the original image and the corrected drawing can be retained in the database for comparison and analysis. This kind of drawing is a new technique and we cannot predict how useful it will be until we have field-tested it. But it is likely that this method will be very useful and we suggest that it be used frequently. To annotate photographs with drawings will become a powerful recording technique. Free Hand Simple/Complex Faint/Distinct View Angle Real/Synthetic Amateur/Professional