CkHybridizationArray - Laboratory of Computational Biology

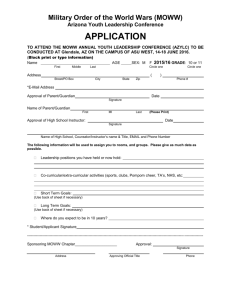

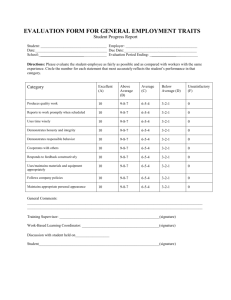

advertisement

Project in Bioinformatics:

Applying Ck

Hybridization

Arrays in Expression Profiling – a

Theoretical Study

By

Yoav Pinsky

I.D. 031986789

Idan Rubin

I.D. 034039107

May 2003

Table of Content

1

Introduction .................................................................................................. 3

1.1

Basic terms .......................................................................................... 3

1.2

The Vision........................................................................................... 4

1.3

Goal of project .................................................................................... 4

1.4

Theoretical Idea .................................................................................. 5

2

Description of project .................................................................................. 6

2.1

Work stages......................................................................................... 6

2.1.1

Stage I – Synthetic data, binary signatures ......................................... 6

2.1.1.1

Data sets ........................................................................... 6

2.1.1.2

Hybridization signature calculation ................................. 6

2.1.1.3

Noise modeling ................................................................ 7

2.1.1.4

Pseudo-inverse ................................................................. 7

2.1.1.5

Solution quality................................................................ 7

2.1.2

Stage II – Yeast sequences data, quantitative signature ..................... 8

2.1.2.1

Data sets ........................................................................... 8

2.1.2.2

Hybridization signature calculation ................................. 8

3

Results .......................................................................................................... 9

3.1

Synthetic (Random) data .................................................................... 9

3.2

Yeast data .......................................................................................... 10

3.2.1

Data set ............................................................................................. 10

3.2.2

Building the signature matrix ........................................................... 10

3.2.3

Calculating the pseudo-inverse of each matrix ................................. 11

3.2.4

Performing the experiments .............................................................. 11

4

Analyzing the results ................................................................................. 12

4.1.1

SQ1 .................................................................................................... 12

4.1.2

SQ2 .................................................................................................... 15

4.1.3

SQ3 .................................................................................................... 16

4.1.4

SQ4 .................................................................................................... 18

5

Dealing with under-determined matrices ................................................... 19

5.1

The problem ...................................................................................... 19

5.2

The solution ...................................................................................... 19

References ........................................................................................................... 21

Appendix A - Work Stages summary ................................................................. 22

Appendix B – Future work ................................................................................. 23

Appendix C – Hardware & Software specifications ........................................... 24

Appendix D – CD with C code, matlab scripts, graphs and data

2

1

Introduction

In any living cell that undergoes a biological process; different subsets of the

total set of genes encoded in the organism’s genome are expressed in different

stages of the process. The particular subset expressed at a given stage and its

quantitative composition is of extreme importance. Being able to measure subsets

of genes that express themselves in different stages, different cells, and different

organisms is instrumental in understanding biological processes. Such information

can help the characterization of sequence-to-function relationship and the

determination of effects (and side effects) of experimental treatment. The most

successful and most widely used techniques for measuring expression profiles

utilize specifically designed surface-bound probes in an assay based on

hybridization arrays. One example of an existing generic method that doesn’t

require prior determination of the RNA to be measured is SAGE (ref. 1).

In this work we study theoretical and feasibility aspects of a generic micro-array

based approach to expression profiling, from the computational point of view.

1.1

Basic terms

Gene expression profiling assay – is an assay that measures the expression

levels of a set of genes in a mixture.

Hybridization array – is a set of oligonucleotides immobilized on a surface.

When a fluorescent-labeled target DNA (or RNA) mixture is introduced to

such an array, the resulting fluorescence pattern is indicative of the mixture’s

content.

Generic hybridization array – as opposed to specific or custom array, which is

used by today’s applications, is a hybridization array that contains probes that

do not depend on the assays specific target. For example, a Ck array, that is an

array that contains all 4k k-mers (DNA/RNA oligonucleotide of length k). In

3

this work we focus on Ck arrays, and when we write hybridization array, we

refer to a Ck generic array, unless otherwise indicated.

Hybridization signature – The fluorescence-pattern induced by introducing a

solution of RNA/DNA sequences to the generic hybridization array.

Hybridization signature matrix – a matrix of some hybridization signatures.

Each column in the matrix is a hybridization signature of one RNA sequence.

Concentration vector - a vector containing the concentrations of each type of

RNA sequence in a mixture.

Melting curve – a graph / function that indicates the annealing factor of two

specific RNA / DNA strands for any given temperature.

1.2

The Vision

Given a mixture of many different RNA strands (with known sequences), we

want to determine the expression levels of each sequence in the mixture, using a

generic array based hybridization assay, and our knowledge of the hybridization

signatures of each component of the mixture.

1.3

Goal of project

In this project we will study the theoretical feasibility of applying generic array

designs to expression profiling. We examine the following question: what is the

quantitative effect of the noise variance on the hybridization array’s performance?

To be more specific: how large can random (Gaussian) noise in the fluorescencepattern get, and still be tolerated by a generic hybridization array? (Tolerated noise

here means that the array still yields the right answer, with high probability,

measured according to some reasonable probability measures on the input space).

4

1.4

Theoretical Idea

Consider a mixture of known RNA sequences. We try to determine the expression

levels of each RNA molecule in the mixture by performing the following:

1. We get the hybridization signature of the mixture, b, by performing a simple

hybridization assay.

2. We calculate the hybridization signature of each RNA sequence that might be

preset in the mixture, based on its sequence, and construct a hybridization

matrix A. Each column in the matrix is a hybridization signature of one

sequence.

3. To find the concentration vector, we use the pseudo-inverse of the

hybridization matrix, and find the vector, x, that gives us the best approximate

solution to the equation system: Ax = b

This will work if the hybridization signature is linear in the relative concentration

of the different RNA molecules in the mixture. In reality this is not the case, but

we assume that it is approximately linear. If we had an "ideal" system, under the

linearity assumption, and the matrix A was non-singular, the process described

above would give us the exact and unique concentration vector b.

Unfortunately we have some factors that can cause an error in our results:

1. The accuracy of the calculated hybridization signature of each gene.

2. The accuracy of our instruments - when we measure the hybridization

signature of the mixture.

3. The hybridization kinetics of each sequence in the mixture can be slightly

different than the hybridization in a pure solution.

We treat all these factors as noise, and want to find out how this noise affects

the accuracy of our calculated concentration vector.

5

2

Description of project

We start by describing the general flow that we used for finding the relationship

between the standard deviation of the noise and the quality of the theoretical result

concentration vector:

We choose a set of genes and compute the hybridization signature of each

member. To compute this signature we use a simple approximated thermo

dynamical model.

We randomly draw a mixture of genes (a concentration vector) in a uniform

(in [0, 1]) and independent manner and compute the corresponding linear

combination of the pure analytes (mRNA molecules) signatures. Under the

linearity assumption, in the absence of experimental error and under the

thermo dynamical model assumed, this should represent the hybridization

signature of the mixture.

We add a randomly drawn noise and try to solve (in the least square error

sense) the resulting equation.

We iterate over various noise variances and study the quality of the solution as

a function of the noise variance.

2.1

2.1.1

Work stages

Stage I – Synthetic data, binary signatures

2.1.1.1

Data sets

As the RNA components of the simulated mixture we used sets of 500 random

sequences of random length from 500 to 1000 bases.

2.1.1.2

Hybridization signature calculation

We started with a very simple (and unrealistic) model, placing 1 in the array cell if

there was a perfect match between the oligonucleotide in the cell and the sequence

(meaning the sequence contains the oligonucleotide), and 0 otherwise (the

sequence does not contain the oligonucleotide). In stage II we study a more

6

quantitative model

2.1.1.3

Noise modeling

We modeled the noise in 2 different ways:

1. Additive noise - By adding a noise factor to each cell in the "ideal" signature

of the mixture (calculated by multiplying the hybridization matrix with a

concentration vector). The noise factor we used is a random variable X, with

normal distribution. X ~ Normal (0, σ 2).

2. Multiplicative noise - By multiplying each cell of the "ideal" signature of the

mixture by eX, where X is again a random variable with normal distribution.

X ~ Normal(0, σ2).

2.1.1.4

Pseudo-inverse

We used MATLAB pinv function to calculate the pseudo-inverse of the

hybridization matrix.

2.1.1.5

Solution quality

We used three different ways to measure the difference between the calculated

concentration vector, and the "real" concentration vector (unknown in a real

experiment, randomly generated by us in our simulations).

1. Euclidian:

∑ (resulti - reali) 2

the most popular but gives much more weight to large errors, not taking into

account the original concentration (summing absolute errors). We used the

Pseudo-inverse matrix to calculate the original concentration vector back from

the signature of the mixture. The Pseudo-inverse gives us the optimal solution

vector in the Euclidian metric. The concentration vector we get will be the one

that gives a hybridization signature (as obtained from multiplying by A) with

the smallest Euclidian distance from the signature we started from (with the

added noise).

2. Log division: ∑ | log (resulti / reali ) | (if resulti is negative we treat it as zero)

gives equal weight to errors in high and low concentration sequences. This

function measure multiplicative rather than additive error.

7

3. Relative error: ∑ ((resulti – reali) / reali) 2

gives equal weight to errors in high and low concentration sequences. This

measures the error relative to the original concentration.

2.1.2

Stage II – Yeast sequences data, quantitative signature

2.1.2.1

Data sets

We used real genes sequences (Yeast ORF sequences) taken from the Yeast

genome database.

SGD ftp site:

ftp://genome-ftp.stanford.edu/pub/yeast/

SGD web site:

http://www.yeastgenome.org/

2.1.2.2

Hybridization signature calculation

We used a temperature-dependent hybridization model. This model is not

completely realistic, but a rough approximation designed to understand the

phenomenon in general but not the details:

In case of mismatch - we write 0 (meaning no hybridization).

In case of match - we write the result of the following function:

f(t) =

f(t) is the hybridization affinity of two sequences in temperature t.

That means that in a mixture of two complementary sequences at temperature t,

we expect f(t) percent of the strands to be in the double-strand form, and the rest

in a single strand form.

The parameter Tm is defined to be the temperature where 50% of the RNA/DNA

strands are connected to the complementary oligonucleotides in the array cell, and

the parameter a controls

Melting curves for some 5-mers

1

0.9

This function is 1 at -∞,

0.8

0.5 at Tm and 0 at +∞.

In the figure we can see

the melting curves of

some pairs of sequences.

If we perform a

Precent of hybrid strands

the slope of the function.

TTTTT-AAAAA (Tm=10)

AAACT-TTTGA (Tm=12)

ACACA-TGTGT (Tm=14)

CCAAA-GGTTT (Tm=16)

GGGGT-CCCCA (Tm=18)

GGGGC-CCCCG (Tm=20)

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

hybridization experiment

0

5

10

8

15

Temperature

20

25

with a mixture of 5-mers, in a temperature of 15 degrees (dashed line), for

example, each pair of 5-mers will connect according to the value where its melting

curve cross the 15 degrees line. The difference in the melting curves arises from

the different Tm each pair of strands has.

To determine the Tm parameter we used the following simplistic rough estimate:

Tm(seq) = 4*[number of C/G bases] + 2*[number of A/T bases]

3

Results

3.1

Synthetic (Random) data

Figure 3.1 below shows the relation between the standard deviation (STD) of the

noise random variable X, and the error in the calculated concentration vector.

This experiment was done on 500 random genes of random lengths (500-1000

bases).

The hybridization signature was calculated with the melting curve function at a

temperature of 14 degrees.

The noise function is the exponential one. The quality of the solution is assessed

by least squares, normalized by number of genes (see equation 6.1).

Each point in the graph is a result of 30 experiments with random noise and

random concentration vectors. The top line is the maximum error out of the 30

experiments, the bottom line is the minimum error and the blue line is the average

error.

The average line is approximately linear as depicted, and we will use this fact later

in our experiments.

-4

5

x 10

Figure 3.1

Average

Linear fit for average

Max

Min

4.5

4

Data: 500 random sequences, each

one 500-1000 bases long.

3.5

Error

3

Signature matrix: melting curve

2.5

function on 14 degrees.

2

Additive Noise STD:

1.5

0.001, 0.003, 0.005,…,0.1

1

30 repeats for each STD value.

0.5

0

1

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

exp(STD of noise)

1.6

1.7

9

1.8

Figure 3.1

3.2

Yeast data

The final stage of our project was to try and use the methods we developed on

actual genomic data sequences.

3.2.1

Data set

We decided to use the Yeast ORF database as a model for our experiments

because it is widely used by many researchers; it is small enough for computing

resources (about 6000 ORF’s), and it is used by biologists as a model for the

Human genome.

We downloaded the Yeast ORF sequences from the SGD ftp site. We wrote a

simple parser and used it to convert the data from the original FASTA format to a

plain text format: each sequence in a single line.

3.2.2

Building the signature matrix

We wrote a C program to calculate the hybridization signature of the sequences.

This program read the sequences from the text file one by one, and calculates the

signature of each sequence for a defined Ck array in a given temperature.

The program is generic and can use any user-defined function to calculate the

expected hybridization in each cell of the Ck array. This user-defined function gets

two DNA strands as C-style strings, and returns a number between 0 and 1, which

reflects the percent of hybridization between the two strands.

The output of the signature program is a text file that contains the hybridization

signature matrix earlier referred to as A.

We used the generic signature program to get the hybridization matrices of 6-mers

array and 7-mers array, using both the zero-one hybridization model and the

melting-curve hybridization model in two different temperatures.

10

3.2.3

Calculating the pseudo-inverse of each matrix

We loaded each signature matrix in MATLAB and calculated the pseudo-inverse

using the built-in pinv function.

To avoid redundant columns in the matrix (duplicates of the same signature),

caused by duplicated genes in the DB, we used MATLAB's built-in unique

function before calculating the pinv.

In this stage we encountered a space complexity problem - MATLAB could not

perform the pinv function on our 7-mer signatures matrix array. We used a

pentium-4m computer with 512 MB of RAM, but the size of such a matrix is 47 *

genes = 16384 * 6000 = 98304000 double cells = 750 MB of memory. Moreover,

this calculation demands twice this size, for the pinv result is also a matrix of the

same size.

Thus we where limited to performing our experiments on 6-mers matrices, which

does not allow us to use all 6000 genes. This is because such the matrix would be

under-determined. We chose to do our experiments on a maximum of 3000 genes,

which we hope will serve as a good model also for the whole 6000.

3.2.4

Performing the experiments

In this stage we simulated a gene expression experiment using Ck array, and

measured the effect of noise on the calculated concentration vector.

We start with a hybridization signatures matrix A, and it's calculated pinv pA.

We used a 6-mer Ck array, on 2991 genes, so the size of A was 4096*2991.

1. We draw a concentration vector for the genes:

v = (e1, e2, …,e2991) where ei ~ U(0,1) + 0.000001

We added 0.000001 to prevent a case of non-expressed genes.

2. We calculated the hybridization signature of the gene mixture on the array:

s = Av

11

3. We choose a standard deviation value s, and draw a noise factor for each cell

in the signature array:

Noise = (n1,…n4096) where ni = Norm(0, σ2)

4. We get a noisy hybridization signature by multipling each cell with the

exponent of a random noise value:

s' : { s'i = si * eni | i = 1…4096 }

5. We calculate the concentration vector out of the noisy array, using the pseudoinverse of the original signatures matrix:

v' = pinv(A) * s'

6. Now we measure the quality of our solution with 4 different functions:

6.1

SQ1 = (1 / ∑i vi) * ∑i |vi - v'i|

( i=1…n, n = number of genes )

this is the average delta between the real and the calculated concentration

vector on each gene.

6.2

SQ2 =

(1 / ∑i vi2) * ∑i (vi - v'I) 2

this is the Euclidian distance between the real an calculated concentration

vectors.

6.3

SQ3 = (1 / n) * ∑i |vi - v'i| / vi

this is the average relative error of each gene's concentration vectors.

6.4

SQ4 = (1 / n) * ∑i |log (v’i / vi)|

this is the log of the relative errors of each gene's concentration vectors.

4

4.1.1

Analyzing the results

SQ1

SQ1 = (1 / ∑i vi) * ∑i |vi - v'i|

Lets look at an experiment on 1000 Yeast genes, with noise standard deviation of

0.01. The vector delta = v - v' is our prediction error. This vector values are

distributed normally with average = 0, and std = 0.0765 as shown in figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 is a histogram of the values in the delta vector.

12

The mean of absolute values of delta, was

150

0.0559 in this case. This is the average

100

concentration error we have for each gene.

50

To normalize this value, we divide this number

0

-0.4

by the average concentration value:

-0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

Figure 4.1

(1/n) *∑i vi = 0.5075

so the SQ1 score in this case is 0.0559 / 0.5075 = 0.1101

this gives us the SQ1 value:

(1 / ((1/n) * ∑i vi ))) * (1/n) * ∑i |vi - v'i| =

(1 / ∑i vi) * ∑i |vi - v'i| = SQ1

so SQ1 is the average concentration error, normalized by the average of the

concentration values.

In figure 4.2 we see a graph of SQ1 values for different standard deviation of the

noise. For each noise STD, we ran 50 experiments. The graph shows the

maximum, average and minimum SQ1 values, out of the 50 experiments.

1000 genes, 50 experiments

1.2

Avg

Linear fit (slope = 11.79)

Max

Min

1

Figure 4.2

Data: 1000 Yeast genes

Error (SQ1)

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

0.8

melting curve function calculated

at 18 degrees.

0.6

Noise STD:

0.4

0.001, 0.003, 0.005,…,0.1

50 repeats for each STD value.

0.2

0

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

STD of noise

0.08

0.1

Figure 4.2

We see that there is a linear relation between the STD of the noise, to the SQ1

average score. In the 1000 genes example shown in figure 4.2, the slope of the

linear fit to the average line, is 11.79.

Based on this result, we can say that when we perform a gene expression assay

13

with our model on 1000 genes and a 6-mer array, the expected average error we

will get equals: expected average error = 11.79 * STD of noise

So if we want, for example, to calculate the expression vector of 1000 genes, using

6-mer Ck array, with an average error of 0.1 (at SQ1 normalized units), we should

lower our noise factors STD to at most 0.1 / 11.79 = 0.00848.

Figure 4.3 shows the results of the same experiments but for 3000 genes.

9

Figure 4.3

Avg

Linear fit (slope = 83.25)

Max

Min

8

7

Data: 3000 Yeast genes

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

melting curve function calculated

5

at 18 degrees.

4

Noise STD:

3

0.001, 0.003, 0.005,…,0.1

2

50 repeats for each STD value.

1

0

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

STD of noise

0.08

0.1

Figure 4.3

The relation is still linear but with a much stronger slope of 83.25 .

This result probably relate to the larger condition number of the signatures matrix

(see appendix B – future work).

Figure 4.4 shows the relation between the number of genes in the concentration

vector (and signatures matrix), and the slope of average SQ1 score. These are the

results from experiments made on a 6-mer Ck array.

Figure 4.4

80

70

Data: 500 - 3000 Yeast genes

Slope of SQ1 average score

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

60

Slope

Error (SQ1)

6

melting curve function calculated at

50

18 degrees.

40

Noise STD:

30

0.001, 0.003, 0.005,…,0.1

20

50 repeats for each STD value.

10

0

500

14

1000

1500

2000

Number of genes

2500

3000

4.1.2

SQ2

SQ2 =

(1 / ∑i vi2) * ∑i (vi - v'I) 2

Using the SQ2 score we get similar results. In figure 4.5 we show the results on

1000 genes. On figure 4.6 are the slopes for different sizes of gene sets.

The SQ2 results are a little different from SQ1 results, maybe because SQ2 function

gives more weight to larger errors. We should remember that in order to get the

concentration vector back from the hybridization signature vector, we used the

pinv method – that guarantees an optimized solution in the least square sense. So

1000 genes, 50 experiments per STD

1.5

Figure 4.5

Data: 500 - 3000 Yeast genes

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

1

SQ2

melting curve function calculated

at 18 degrees.

Noise STD: 0.001…0.1

0.5

Avg

Linear fit (slope = 14.32)

Max

Min

0

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

STD of noise

0.08

50 repeats for each STD value.

0.1

Figure 5.5

Figure 4.6

150

Slope of SQ2 average score

Data: 500 - 3000 Yeast genes

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

Slope

100

melting curve function calculated at

18 degrees.

50

Noise STD:

0.001, 0.003, 0.005,…,0.1

0

500

1000

1500

2000

Number of genes

Figure 4.6

2500

3000

15

50 repeats for each STD value.

the SQ2 method is the natural way for measuring our results quality.

4.1.3

SQ3

SQ3 = (1 / n) * ∑i |vi - v'i| / vi

We are now interested in measuring the relative error of our solution.

vi - v'i is the delta between the real concentration of the i-th gene and it’s

calculated concentration. So |vi - v'i| / vi is this error divided by the real

concentration, in other words: the relative error of the calculated concentration.

The sum of all relative errors divided by the number of genes (n) is the average

relative error.

So the SQ3 score represent the average relative error of a calculated

concentration vector.

note that: |vi - v'i| / vi = | 1 - v'i / vi | (when vi and v'i are positive), so Ri = v'i / vi is

the value we are interested in.

Ri є [0, ∞), and Ri = 1 when v’i = vi .

Let’s look at another example of an experiment, calculating the concentration

vector of 1000 Yeast genes using a 6-mers signatures matrix, built using the

melting curve function on 18 degrees, with noise STD of 0.01 .

80

Figure 4.7

Histogram of vi / v'i values

60

Grouped by logarithmic centers.

40

Data: 1000 Yeast genes

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

20

melting curve function calculated at

0

-0.2

10

-0.1

10

0

10

0.1

0.2

10

10

18 degrees.

Noise STD: 0.01

Figure 4.7

We see that on a logarithmic scale, R values are distribution is approximately

normal, with mean of 1. About 13% of the values of R are smaller than 2/3 or

larger than 3/2 = 1.5 . We consider these large relative errors, and it is interesting

to look at the concentrations in which these errors occurred.

The average concentration in the concentration vector is 0.4829 .

But when we calculate the average concentration only on the places in the vector

that have 2/3<Ri<3/2 we get a mean concentration of 0.1385 . This points to the

fact that the small concentrations are those who get a large relative error.

In our example, the SQ3 score, which is the average relative error, is 0.74 (74%).

The SQ3 score of the concentrations larger than 0.1 (which populate 88% of the

concentration vector) was 0.14 (14%).

The problem of large relative error in small concentrations is bound to happen

when we use the least squares norm pseudo-inverse in our calculations and this

16

norm gives more weight to large absolute errors, ignoring the relative errors. It is

possible to create a pseudo-inverse matrix based on a different norm that will

consider the relative error (see appendix B – future work).

Figure 4.8 shows SQ3 scores for different noise STD on 3000 genes.

30

SQ3 score

Figure 4.8

25

SQ3 scores vs. noise STD

20

Data: 3000 Yeast genes

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

15

melting curve function

10

calculated at 18 degrees.

Avg

Linear fit (slope = 403.25)

Max

Min

5

0

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

STD of noise

0.05

0.06

Noise STD: 0.001...0.07

50 repeats for each STD value

0.07

Figure 4.8

Figure 4.9 shows the slopes for different numbers of genes.

500

Figure 4.9

Slope

Slope of SQ3 average score

400

Data: 500-3000 Yeast genes

300

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

melting curve function calculated

200

at 18 degrees.

100

0

500

Noise STD: 0.01

50 repeats for each STD value

1000

1500

2000

Number of genes

2500

3000

Figure 4.9

17

4.1.4

SQ4

SQ4 = (1 / n) * ∑i | log (v’i / vi ) |

Another way of exploring the relative error of our solution is to look on the log

of R.

log Ri = log |v'i / vi |

Like in the example from the previous section, we see that the distribution of the

values of log R is approximately normal, with mean 0. the maximum value in

this example is 4.6, and minimum is -5.7, this gives us another perspective on

the data, in which we can measure the relative error.

A histogram of log R values is shown in figure 4.10 .

200

Figure 4.10

Histogram of Log(CV’i / CVi)

150

values.

100

Data: 1000 Yeast genes

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

50

melting curve function calculated

at 18 degrees.

0

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

Noise STD: 0.01

Figure 4.10

res-file: sign-6-orf-coding-hyb-18-3000.mat genes:2991 repeats:50

7000

Figure 4.11

6000

Data: 3000 Yeast genes

ESQ4 score

5000

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

4000

melting curve function calculated

3000

at 18 degrees.

2000

1000

0

Noise STD: 0.001 … 0.1

Avg

Max

Min

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

STD of noise

0.08

50 repeats for each STD value

0.1

Figure 4.11

18

5

5.1

Dealing with under-determined matrices

The problem

When we try to get a concentration vector of m genes, using a hybridization array

of n = 4k cells, and m > n, we face the problem of an under-determined matrix. It

is like trying to solve an algebric problem of 3 variables, with only 2 equations.

The solution space for such a problem is infinitely large.

5.2

The solution

The proposed solution to this problem, is to produce another set of “equations” by

building a second hybridization signatures matrix, at a different temperature.

For example, lets say we have a mixture of 6000 genes. We want to use a 6-mers

array, to get the concentration vector of our genes, so we calculate the

hybridization signatures matrix at a temperature of 18 degrees. We got an underdetermined matrix A18 with N x M = 4096 x 6000. Then we produce another

matrix A15 at a temperature of 15 degrees. To get our concentration vector, we use

the vertical concatenation of the two matrices:

[A15]

A15, 18 =

[A18]

the size of A15, 18 is 8192 x 6000, and we can use this matrix to get our

concentration vector.

We tested this idea on concentration vectors of 2000 genes, using a 6-mers array.

This way we could compare our results to the previous experiments with 2000

genes. The reason for not using more genes was again the space complexity

limitation: MATLAB could not load two 4096 x 6000 matrices, and compute their

pinv, and could not even perform this operation on two 4096 x 3000 matrices.

19

Figure 5.1 shows a comparison between a regular 18 degrees hybridization matrix

SQ1 scores shown before, and the 2 temperatures (15, 18 degrees) matrix SQ1

scores. We can see a nice improvement in the quality of the results when using the

2 temperatures matrix.

3

2.5

SQ1 score

Figure 5.1

Normal Average (slope = 33.5)

2 temp Average (slope = 23.3)

Data: 2000 Yeast genes

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

2

melting curve function

1.5

calculated at 18 degrees, and

1

15 degrees.

0.5

0

Noise STD: 0.001…0.01

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

STD of noise

0.08

0.1

Figure 5.1

Figure 5.2 shows the relative error comparison using SQ4 (log) scores.

It is evident that the use of the 2 temperatures matrix improved the result quality

also in the relative error sense.

Figure 5.2

1.2

Data: 2000 Yeast genes

SQ4 score

1

Signature matrix: 6-mer array,

0.8

melting curve function

0.6

calculated at 18 degrees, and

0.4

15 degrees.

Normal Average

2 temp Average

0.2

0

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

STD of noise

0.08

Figure 5.2

20

Noise STD: 0.001…0.01

0.1

References

1. Serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) is a tool that allows the analysis of

overall gene expression patterns with digital analysis. Because SAGE does not

require a preexisting clone, it can be used to identify and quantitate new genes

as well as known genes.

http://www.sagenet.org/

2. Alon, U., Barkai, N., Notterman, D., Gish, K., Ybarra, S., Mack, D. & Levine,

A. J. (1999), ‘Broad patterns of gene expression revealed by clustering

analysis of tumor and normal colon tissues probed by oligonucleotide arrays’,

Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 6745–6750.

3. DeRisi., J., Iyer, V. & Brown, P. (1997), ‘Exploring the metabolic and genetic

ontrol of gene expression on a genomic scale’, Science 282, 699–705.

4. Lockhart, D. J., Dong, H., Byrne, M. C., Follettie, M. T., Gallo, M. V., Chee,

M. S., Mittmann, M., Want, C., Kobayashi, M., Horton, H. & Brown, E. L.

(1996), ‘DNA expression monitoring by hybridization of high density

oligonucleotide arrays’, Nature Biotechnology 14, 1675–1680.

21

Appendix A - Work Stages summary

** proposed as future work

Data Sets:

-

Random sequences. Length 500-1000.

-

Yeast ORF sequences. ~6000 sequences.

Signature Calculation:

-

match / mismatch (1 / 0)

-

Hybridization function: 1 / (exp(a(x-Tm))+1)

Noise modeling:

Let X be a random variable with normal distribution: X ~ Normal (0, σ2)

Let W be the real hybridization signature of a mixture, then W’ is the

experimented hybridization signature, which is the real signature with some noise.

-

noise = X

-

noise = eX

W’ = W + noise

W’ = W * noise

Pseudo-inverse norm:

-

Least squares: sum(Wi – Wi') ^ 2

-

** Percentage: sum (Wi – Wi' / Wi) ^ 2

-

** Logarithmic: sum | log |Wi / Wi’| |

Result quality measurement function:

-

Least squares: sum(Wi – Wi') ^ 2

-

Normalized least squares: sum(Wi – Wi’) ^ 2 / number of genes

-

Percentage: sum (Wi – Wi’ / Wi) ^ 2

-

Logarithmic: sum | log |Wi / Wi’| |

Results

Draw graphs for all experiments.

Compare results with different parameters:

-

Number of genes

-

Ck size (3-mer = 64, 4-mer = 256, 5-mer = 1024, 6-mer = 4096, 7-mer =

16384, 8-mer = 65536)

-

Random / Yeast data.

22

Appendix B – Future work

Solve under-determined matrix equation by using 2 temperatures on same set of

genes, and getting a double length array. Compare results of this method to the

regular method.

Pseudo-inverse norms:

We saw that using the basic pseudo-inverse norm (L2) does not give us good

results on relative error measurements. If we are interested in lowering the relative

error, it is possible to define a different norm that will give more weight to larger

relative errors. This norm would look something like | vi – v’i | / vi which is

actually a family of norms. We can use these norms to create a pseudo-inverse

matrix that will minimize the relative error of the result.

More research can lead to a norm that will lower the values of |log v’i / vi |.

Differential expression

Compare expression vector delta (can we discover the genes that were over/under

expressed)

Condition number

Explore the connection between the signature matrix condition number and the

results.

Extending the hybridization model

Improve the hybridization model by taking mismatches into account and refine the

melting curve function.

23

Appendix C – Hardware & Software specifications

Hardware

We used an HP mobile computer, with a Pentium - 4m processor, running at 1.6

GHz, with 512 MB of RAM.

Software

We used MATLAB 6.1 for all the experiments.

We wrote some C programs to produce the signature matrices, and to convert the

Yeast ORF files from FASTA format to plain text files.

Space requirements

Here are some examples:

File

Size

7-mers signatures matrix of 6000 genes

915 MB (zipped: 15 MB)

6-mers signatures matrix of 6000 genes

228 MB (zipped: 6 MB)

4096 x 3000 matrix loaded in MATLAB

96 MB of RAM

Time

It took MATLAB about 5 minutes to calculate the pinv of a 4096 x 6000 matrix.

C Programs

Signature maker

C program used to build signature matrices.

input: The program read a plain text file that contain one gene in each line.

Output: a text file with each gene’s hybridization signature, based on the generic

definitions of Ck array (K-mer), hybridization function and temperature.

Fasta parser

C program used to convert FASTA files to the format readable by the Signature

maker.

input: a text file in FASTA format.

Output: a text file with one gene in each line.

24

MATLAB scripts

Analyze signature

run the concentration experiment on some noise STD.

input: signature matrix, pinv of that matrix, STD vector (the script perform the

experiments on each value in the vector), repeats (how many experiments to

perform for each noise STD)

Output: a res construct that contains the results of all the experiments.

Plot results

Plot the results of a series of experiments.

Input: res construct and number of quality measurement function.

Output: a graph of the average, max and min results vs. the STD vector.

25