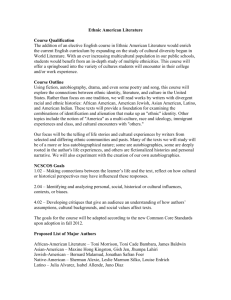

DRAFT - Metropolis Canada

advertisement