Pest Risk Assessment of Cucumber vein yellowing virus – D.R.

advertisement

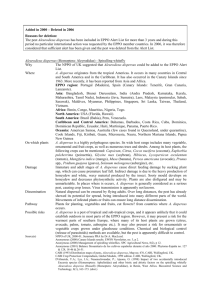

Pest Risk Assessment of Cucumber vein yellowing virus – D.R. Jones, CSL, York, UK, 21/11/01, PPP 9740 02/9152 PPM Point 6.2 SUMMARY PEST RISK ASSESSMENT 1. Name of Pest: Cucumber vein yellowing virus (CVYV) 2 (a) Does it occur in the UK/EU/EPPO region or arrive regularly as a natural migrant ? UK. CVYV is not present in the UK. EU/EPPO. The virus is present in Spain in the EU as well as Israel, Jordan and Turkey in the EPPO region. (b) Is there any other reason to suspect that the pest is already established in the UK ? No 3. EU Directive status ? None. 4. EPPO status ? None 5. What are its host plants ? CVYV naturally infects cucumber (Cucumis sativus) (Cohen and Nitzany, 1960) and melon (Cucumis melo) (Yilmaz et al., 1989). Wild cucurbits are also reported as natural hosts in Jordan (Mansour and Al-Musa, 1993). There are no reports of seed transmission. In artificial inoculation experiments, Citrullus colocynthis (bitter apple), Citrullus lanatus (watermelon), Cucumis melo (muskmelon), Cucumis melo var. flexousus (snake cucumber), Cucumis sativus (cucumber), Cucurbita foestidissima (buffalo gourd), Cucurbita moschata (pumpkin), Cucurbita pepo (squash), Lagenaria vulgaris (bottle gourd) were found to be susceptible. Those infected without symptoms were the ‘Alfa’, ‘Florida’ and ‘Mallali’ cultivars of C. lanatus, the ‘Aravi’ cultivar of C. melo and non-parthenocarpic cultivars of C. sativus. (Cohen and Nitzany, 1960; Mansour and Al-Musa, 1993; Al-Musa et al., 1984: Yilmaz et al., 1989) (a) Highlight the crop plants grown economically, including those of environmental or amenity value, in the UK (and EU/EPPO) (include figures for potential yield/quality losses): Cucumber and melon are seen as being at risk in the UK, EU and EPPO. In the UK, the protected cucumber crop of 1999 has been provisionally valued at £38,465,000 (Anon., 1999). If Bemisia tabaci, the vector of CVYV, becomes established in glasshouses in the UK, then these crops would be at risk. Yield losses are difficult to predict as this would depend on the percentage of plants initially infected and the level of infestation of the whitefly vector. In a ‘worst case’ scenario, all plants may be infected possibly resulting in a substantial drop in yield. Yield losses of individually infected plants have not been determined. 1 Pest Risk Assessment of Cucumber vein yellowing virus – D.R. Jones, CSL, York, UK, 21/11/01, PPP 9740 Cucumber is grown throughout the EU/EPPO region with melon most commonly grown in Mediterranean countries. (b) Are any of the host plants of Forestry importance ? No 6. What is its present geographical distribution ? Asia: No record Africa: No record North America: No record Central America and the Caribbean: No record South America: No record Oceania: No record EU: Spain (Cuadrado et al., 2001a, b) EPPO region: Spain (Cuadrado et al., 2001a, b), Israel (Cohen and Nitzany, 1960), Jordan (Al-Musa et al., 1985), Turkey (Yilmaz et al., 1989) 7. Does it appear capable of becoming established in the UK/EU/EPPO region ? (a) outdoors. Field grown crops of natural hosts may not be affected in the UK and other countries in the northern EU/EPPO region as B. tabaci, the vector of CVYV, is not expected to survive outdoors in the winter. However, CVYV would be expected to establish itself in the field in southern countries in the EU/EPPO region as the vector is present outdoors in the summer months. (b) on protected crops. Glasshouses are considered suitable environments for CVYV if B. tabaci becomes established. Bemisia tabaci, an EPPO A2 Quarantine Pest, is not established in the UK and interceptions on imports are eradicated. B. tabaci is established in glasshouses in some countries in northern Europe thus facilitating establishment should CVYV be introduced. Crops grown in polyethylene tunnel houses in countries in southern areas of the EU/EPPO region would also be expected to be at risk. The incidence of CVYV in cucumbers grown in protected environments would depend on the populations of B. tabaci and the number of plants initially infected with CVYV. Large, uncontrolled populations of B. tabaci would result in most plants eventually being infected independent of the number of initial inoculum sources. Smaller numbers of whitefly may not result in as many virus-affected plants, but could if there were a large number of initial inoculum sources. 8. What is its potential likely to be as a pest or as a vector of viruses in the UK/EU/EPPO region? UK. CVYV is transmitted by B. tabaci, which is not established in the UK. However, this whitefly is being intercepted regularly on imported plant material and is the subject of eradication when detected. Therefore, although CVYV is unlikely to cause a problem should it be introduced to the UK in cucumber seedlings today, there is a danger that it may become serious should B. tabaci become established in the future. If B. tabaci does become established, it is expected that it will be a glasshouse pest on 2 Pest Risk Assessment of Cucumber vein yellowing virus – D.R. Jones, CSL, York, UK, 21/11/01, PPP 9740 protected crops. The outside environment in the UK and the rest of northern Europe is considered to harsh in the winter for survival of the vector. EU/EPPO. Bemisia tabaci is found in glasshouses in many northern countries in the EU/EPPO region. However, there is no information to suggest that CVYV has been recorded in glasshouses in northern Europe. In the Netherlands, the main exporter of seedlings for the horticultural industry of the EU, the glasshouses used to produce cucumber or melon seedlings for export should be free of B. tabaci to prevent any chance of infection should CVYV become established. If control of B. tabaci breaks down due to a build-up of resistance to insecticides and CVYV is found, then there is a danger that CVYV could be introduced with vegetative propagating material. CVYV would be expected to become a problem in field crops of natural hosts (cucumber, melon) in southern countries in the EU/EPPO region. 9. What are the prospects for continued exclusion ? CVYV could gain entry to countries where the virus is not present, in cucumber or melon seedlings imported from countries with CVYV. Exclusion would be dependent on all imported cucumber and melon seedlings being produced under conditions which guarantee freedom from the virus. It is unlikely that CVYV would be introduced with viruliferous whitefly on non-host plants or produce for consumption. This is because CVYV is carried by B. tabaci in a semi-persistent manner and the whitefly loses the ability to transmit the virus after 4-6 hours (Harpaz and Cohen, 1965). 10. What are the prospects for eradication ? The prospects for eradication of CVYV would be good if outbreaks were confined to a few glasshouses. Field outbreaks in the southern EU/EPPO region would be almost impossible to eradicate. 11. How would eradication be achieved ? If infected plants were found in glasshouses where B. tabaci was not established eradication would be possible by destroying infected plants. If B. tabaci were to become established, eradication would still be possible if outbreaks were confined to a few glasshouses. However, immediate action would need to be taken to kill all whitefly in the glasshouses to prevent the migration of viruliferous B. tabaci. All host plants in the glasshouses would also need to be destroyed. Eradication of viruliferous B. tabaci would be very difficult in a field situation. Attempts to eliminate the virus would have to focus on crop destruction plus the eradication of whiteflies by insecticide spray. 3 Pest Risk Assessment of Cucumber vein yellowing virus – D.R. Jones, CSL, York, UK, 21/11/01, PPP 9740 12. Conclusion CVYV causes an important disease of cucumbers and melons in Israel, Jordan and Turkey. The virus has recently spread to Spain where action has been taken to limit incidence and spread by the destruction of affected crops of cucumber. CVYV is transmitted by B. tabaci, which is present in the field in southern Europe and in glasshouses in many countries in northern Europe. This whitefly is not yet established in the UK, but is regularly intercepted. Should CVYV be introduced to other countries, there is a strong possibility that it may become a serious problem within the EU and EPPO region. Consideration should be given to designating CVYV an EPPO A2 Quarantine Pest and to introducing regulations within the EU to prevent the spread of CVYV in cucumber and melon planting material. Name: David R Jones Address: Plant Health Group, CSL, Sand Hutton, York YO41 1LZ, UK Date: 21 November 2001 13. References Al-Musa, A.M., Qusus, S.J., Mansour, A.N. (1985). Cucumber vein yellowing virus on cucumber in Jordan. Plant Disease 69, 361. Anon. (1999). Basic Horticultural Statistics for the United Kingdom, Calendar and Crop Years 1988-1998. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, UK. Anon. (2000). Council Directive 2000/29/EC of 8 May 2000 on protective measures against the introduction into the Community of organisms harmful to plants or plant products and against their spread within the Community. Official Journal of the European Communities 43 no. L 169 pp. 1-112. Cohen, S. and Nitzany, F.E. (1960). A whitefly transmitted virus of cucurbits in Israel. Phytopathologia Mediterranea 1, 44-46. Cuadrado, I.M., Janssen, D., Velasco, L., Ruiz, L. and Segundo, E. (2001a). Cucumber vein yellowing virus (CVYV) now in Spain. EWSN Newsletter, January 2001, Issue No. 8. European Whitefly Studies Network, John Innes Centre, Norwich, UK, 4 pp. Cuadrado, I.M., Janssen, D., Velasco, L., Ruiz, L. and Segundo, E. (2001b). First report of Cucumber vein yellowing virus in Spain. Plant Disease 85, 336. Harpaz, I and Cohen, S. (1965). Semipersistent relationship between cucumber vein yellowing virus (CVYV) and its vector, the tobacco whitefly (Bemisia tabaci Gennadius). Phytopathologische Zeitschrift 54, 240-248. Mansour, A. and Al-Musa, A. (1993). Cucumber vein yellowing virus; host range and virus vector relationships. Journal of Phytopathology 137, 73-78. Yilmaz, M.A., Ozaslan, M and Ozaslan, D. (1989). Cucumber vein yellowing virus in cucurbitaceae in Turkey. Plant Disease 73, 610. 4