SOCIETY AND ENVIRONMENT

advertisement

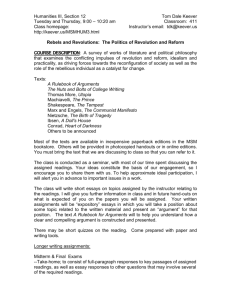

ENVR 201 – 001 SOCIETY AND ENVIRONMENT MWF 11:35-12:25 ENGMC 204 Fall 2004 Instructors: Madhav G. Badami (Urban Planning/MSE) – Course Co-ordinator Oliver Coomes (Geography) Renee Sieber (Geography/MSE) COURSE OUTLINE This course deals with how human activity interacts with and affects the environment, and how our choices as individuals and societies, our political institutions and economic arrangements, and technologies, mediate these interactions and effects. The course will discuss society-environment interactions and environmental issues in various sectors, including air, water, land, agriculture, forestry, fisheries, transport, and energy, and how issues of politics, equity, and how we value the natural environment are inextricably intertwined in the debates around environmental problems. The course deals with questions on which people tend to have strong opinions: What are the causes of human misuse or overuse of our environment? Are there too many people and not enough resources? Can technological fixes solve environmental problems? Can “getting the prices right” solve these problems? Are there limits to economic growth and/or human development? Can we (and how do we) live sustainably and equitably in a global community? The lectures will discuss the readings, raising additional questions and adding information about their significance for understanding society-environment interactions. An important function of the lectures is to critically discuss important but often contested concepts such as “sustainability”, “resources”, “carrying capacity”, and “development”. Wherever possible, case studies will be used, to ground our discussions in the lived reality of societies, and to help students gain a deeper appreciation of theoretical concepts. The lectures will discuss various environmental issues not only in various sectors, but also in different geographical contexts. This approach will allow us to make connections and investigate similarities and differences between environmental issues in different sectors and contexts, and explore the implications of these similarities and differences for addressing these issues in different sectors and contexts. Students will be expected to read extensively and carefully analyze the material in the lectures and readings. They will also need to understand interconnections among case studies and analytic issues presented in the lectures and readings. Be warned that the readings and lectures will not always agree. This reflects the character of the subject, which brings together ideas from many disciplines and stimulates sharp debates concerning environmental issues. 2 How does ENVR 201 intersect with the other three MSE core courses? The Global Environment, ENVR 200, addresses human impacts on global biogeochemistry, and global policy initiatives aimed at controlling them. While we share a concern about human impacts on ecosystems, ENVR 200 focuses more on global biogeochemical effects of industrial activity and international policies aimed at protecting the atmosphere and the oceans. In ENVR 201 we examine a broader range of demographic, socio-economic, technological and institutional processes underlying our impact on essential resources and ecosystem services, and how they can be used and managed in a manner that is sustainable on local and regional geographic scales. The Evolving Earth, ENVR 202, deals with how our environment evolved and how humans came to have such a disproportionate impact on it. We overlap with ENVR 202, for example, on the subject of human land use and its impacts. However, while their focus is on long-term origins and history, we are more concerned with recent land use, resource management, and how unsustainable practices can be reversed. Knowledge, Ethics and Environment, ENVR 203, deals with how people in different cultures think about the environment, and thus with the cultural and philosophical dilemmas encountered when people with different assumptions seek a common environmental ethic. The concern in ENVR 203 is with how people think about their environment, while we are mainly concerned with our material relationships with the environment. Requirements Students are required to attend the lectures, and to carefully study the assigned readings before each class. Students must buy the course pack (collected readings for ENVR 201) at the McGill Bookstore. Additional readings may be assigned as required. Master copies of these readings will be available for photocopying at Copies EUS on the mezzanine floor of the McConnell Engineering Building. Two mid-term exams (each worth 25% of the final mark) have been scheduled, in class, for Wednesday, October 6 and Wednesday, November 10. There will be a three-hour final exam (worth 50% and covering the entire course) sometime during the exam period (the Instructors have no control over the scheduling of the final exam). The exams will consist of short answer questions ranging from definitions of terms and concepts (50-75 words) to problem-solving questions and short essay questions (150-250 words). Questions will stress comprehension of major concepts and issues rather than memorization of facts or details. As the course progresses there will be a gradual transition from questions that focus directly on special items covered in individual lectures and readings, to more general questions that integrate across subjects covered in different lectures, different readings, and even different sections of the course. Questions and (correct) answers will refer only to materials covered in the course. We will try to discuss sample questions before the mid-term exams. We have scheduled an inclass review session before each exam. After each mid-term exam has been marked, we will devote a class session to discussing questions and answers. A student who misses one mid-term exam, and who promptly presents a note showing a valid excuse (illness or family affliction), may receive credit for the course by writing the other mid-term and the final exam. In such cases, the other mid-term exam will be worth 3 33% of the final mark, and the final exam, 67%. Failure to write both mid-term exams means an automatic mark of “J” (“absent”) for the course, unless a student provides convincing evidence of illness or family affliction (“J” is equivalent to “F”). Any student who, due to illness or family affliction, fails to write the final exam must apply to the Associate Dean of his or her faculty for a “deferred” mark, with permission to write a supplemental exam in early May 2005. Otherwise, failure to write the final exam means an automatic “J” for the course. Students who receive a mark of D, F, or J for the course may apply (at the Student Affairs Office) to write the supplemental exam in May. In all other cases, there is no provision for writing make-up exams, nor for resubmitting work, nor for doing additional work to improve one’s mark. Teaching Assistants We have three Teaching Assistants this year: Rotem Ayalon, Philippe Crete, and Robin de Bled. Office Hours The Instructors and Teaching Assistants will be available for consultation during office hours which will be announced in class. Schedule of Lectures and Exams Introduction Sept. 1 The course will be discussed in general terms. Instructors will introduce themselves, discussing their backgrounds, disciplines, and research interests. Resources Are there enough resources to support the human population? There is much controversy over the future status of renewable and non-renewable resources, as well as ecosystem cycles and services that sustain us. Much of this controversy hinges on what we consider a resource to be, how we estimate its abundance, how we access our dependence on it, and whether the way we use it changes as it becomes scarcer. (1) What are “resources”? Are they running out? (Coomes) Sept. 3 Readings Dearden and Mitchell, 1998. “Energy Flows and Ecosystems”. Freedman, 1998. “Resources and Sustainable Development”. Labour Day Sept. 6 Population Does population growth threaten the biosphere? There is great controversy over the causes and environmental consequences of rapid population growth. To grasp the nature of the problem, we must understand: (a) historical and spatial variations in population density and rates of growth; (b) interactions and feedback loops among fertility, morbidity, migration & mortality; (c) 4 demographic trends over the last few millennia, centuries, and decades; and (d) population structure and growth trajectories. (1) (2) (3) (4) Why does population matter? Distributions and densities (Coomes) Population and growth: key factors (Coomes) Population and history; Demographic transition (Coomes) Issues of population policy (Coomes) Sept. 8 Sept. 10 Sept. 13 Sept. 15 Readings Bergman, 1995. “Human Population: The Distribution and the Pattern of Increase”. Raven, Berg, and Johnson, 1997. “Understanding Population Growth”. Raven, Berg, and Johnson, 1997. “Facing the Problems of Overpopulation”. Resource Use, Institutions, and Impacts (1) (2) Replumbing the Planet (Sieber) Water and Conflict (Sieber) Sept. 17 Sept. 20 It is almost preposterous to think of water as a resource in short supply. However, water will likely be one of the most critically stressed resources and the cause of major conflicts in the 21st century. In the above two lectures, we will cover humans rerouting and restructuring the water supply and then resource conflicts surrounding water. Resource conflicts exist between peoples but also between wildlife and humans. We also include issues of privatization and contamination (not necessarily linked) and de-salinization. Readings Reisner, 1993. “Chinatown” and “A Civilization, if You Can Keep It”. McKenzie, 2002. “Water-Resource or Commodity?”. de Villiers, 2002. “Water and Sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa”. Dimitrov, 2002. “Water, Conflict and Security: A Conceptual Minefield”. (3) The Global Fisheries (Badami) Sept. 22 This lecture will discuss the role of open access regimes, technological evolution, and government intervention in the global fisheries crisis, by drawing on case studies in North America and India, and will explore ways in which the crisis may be resolved. Readings McGinn, 1998. “Promoting Sustainable Fisheries”. (4) International Treaties and Antarctic Fisheries (Ellis) Sept. 24 This is a guest lecture by Professor Jaye Ellis of the Faculty of Law and the McGill School of Environment. (5) Food production and livelihood in an Amazonian society (Coomes) Reading Miller, 1994. “Food Resources”. Sept. 27 5 (6) Landfills (Sieber) (7) A Particular Case: Computer waste (Sieber) Sept. 29 Oct. 1 What's waste got to do with it? Where does your garbage go? These two lectures take you beyond reduce, reuse and recycle to some of the thorniest issues in waste production and its management. Who should pay for waste? Polluter or consumer? Waste isn't necessarily viewed as a bad thing. Certain countries have built their economies around accepting and/or reprocessing waste. Reading CBC Marketplace on computer waste Questions, discussion, and review for exam Oct. 4 MID-TERM EXAM 1 Oct. 6 Conceptualizing Society-Environment Interactions (1) Introduction to Environmental Economics (Coomes) Oct. 8 Thanksgiving Holiday (2) Oct. 11 Demand, supply and equilibrium: concepts of economic efficiency, welfare and equity (Coomes) Oct. 13 Readings Field and Olewiler, 1995. “What is Environmental Economics?” Parkin and Bade, 1994. “Demand and Supply”. (3 and 4) Monetary Valuation of the Environment: Theory and Mechanics (Badami) Oct. 15 and 18 Return Mid-term Exam 1 and discuss Oct. 20 (5) Monetary Valuation Case Study: Air pollution (Badami) (6) Critique of Monetary Valuation, and Alternative Approaches (Badami) Oct. 22 Oct. 25 Environmental processes are essential for human life, and play a crucial role in the global economy, yet they have been taken for granted. How might the environment, and human health and life, be valued? The problem is that environmental values are intangible, and hard to define. Further, environmental values such as clean air are not traded on markets. However, economists have developed methods for monetary valuation of the environment. These methods can help account for and internalize environmental externalities and the environmental costs and benefits of public projects, and demonstrate the need for environmental policies, but are fraught with conceptual, technical, philosophical and ethical difficulties. Critics of monetary valuation argue that it is neither appropriate nor necessary to put price tags on nature, and that we can make wise environmental choices without prices. The above four lectures discuss these opposing positions, and suggest alternatives to monetary valuation. 6 Readings Harris, 2002. “Valuing the Environment”. The Economist, 2002. “Never the Twain Shall Meet: Why do economists and environmental scientists have such a hard time communicating?” O’Neill, 2000. “Markets and the Environment: the Solution is the Problem”. (7) Calculating Inputs to the Ecological Footprint and other issues related to the politics of data sources (Sieber) (8) Analysis and Activists (Sieber) Oct. 27 Oct. 29 An ecological footprint is defined as the bioproductive area (land and sea) that would be required to sustainably maintain a region or community's current consumption, using prevailing technology. It is one of several alternatives to cost-benefit analysis and a method of measuring resource use. How are the values for ecological footprint derived? What has been the “footprint” of the ecological footprint calculation? Readings Chambers, Simmons and Wackernagel, 2001. “Footprinting Fundamentals”. Hansson and Wackernagel, 1999. “Rediscovering place and accounting space: how to re-embed the human economy”. Sustainability – Prospects, challenges and strategies We return to the basic questions raised at the start: for example, are there too many people and not enough resources? If so, how can these problems be addressed? We examine fundamental debates: Is the earth threatened by over-population, by poverty, or by excessive consumption? Can dire poverty be eradicated? Can several billion humans live sustainably on this planet? What challenges do we face, and what information, actions, policies, and ethics may be required to increase our chances of a sustainable future? And how do we reconcile the inevitable conflicts and trade-offs? (1) An economist’s perspective on sustainability (Coomes) Nov. 1 Can an economic perspective help us to operationally define what sustainability means? The reading by Solow provides the theoretical background for this lecture. Readings Solow, 1993. “Sustainability: An Economist’s Perspective”. Daily and Ehrlich, 1992. “Population, Sustainability, and Earth’s Carrying Capacity”. (2) Urbanization, Human Activity and Environment (Badami) (3) The Urban Environmental Challenge in Poor Countries (Badami) Nov. 3 Nov. 5 In these two lectures, we will address: the importance of cities from the point of view of local environments and ecological sustainability; global urbanization trends; urbanization, the urban environmental situation, and the ability to deal with urban environmental problems, in rich and poor countries; why the urban environmental challenge is the most serious in the poor countries, despite their low share of global resource consumption; and finally, why, although human activity in cities has significant local, regional and global environmental impacts, cities are likely the optimal scale at which environmental problems may be addressed effectively. 7 Readings Rees, 1992. “Ecological footprints and appropriated carrying capacity: what urban economics leaves out”. Douglass and Lee, 1996. “Urban Priorities for Action”. Questions, discussion, and review for exam Nov. 8 MID-TERM EXAM 2 Nov. 10 (4) Transport in North America: Problems, Prospects, Remedies (Badami) Nov. 12 In this lecture, we will discuss how cultural, economic, technological and politicalinstitutional forces have shaped (and continue to shape) the transport system in North America, how transport and energy subsidies, and externalities, have contributed to sprawl and excessive reliance on cars, and how transport planning to provide for growing automobile use has created a vicious circle in which automobile reliance and inefficient land use patterns reinforce each other. We will then discuss how this vicious circle may be broken through “full-cost” pricing and other policies, and the potential benefits of these approaches, by drawing on the European experience. Readings Hanson, 1992. “Automobile Subsidies and Land Use: Estimates and Policy Responses” Pucher, 1988. "Urban Travel Behavior as the Outcome of Public Policy: the Example of Modal Split in Western Europe and North America." (5) Hydrogen and all That … (Badami) Nov. 15 The transport sector has serious implications for climate change and energy security, in addition to producing adverse local and regional impacts. Transport accounts for a quarter of energy consumption and carbon dioxide emissions, and nearly half the petroleum consumption worldwide. North America alone accounts for 35-40% of the energy consumed and carbon dioxide emitted worldwide by the transport sector, with just 5% of the population. Finally, energy consumption is growing the most rapidly in the transport sector in North America. The need to increase the use of alternatives to oil in the transport sector is therefore highly desirable, but this sector is also the most challenging from this perspective. This lecture will discuss these challenges, and explore the potential of alternative fuels to contribute to energy security and air pollution and carbon dioxide emission reductions, by means of a case study focused on hydrogen. (6) The roots of environmental racism (Sieber) (7) Movement interactions (Sieber) (8) Women and the environment (Sieber) Nov. 17 Nov. 19 Nov. 22 This set of three lectures focuses on environmental equity, social justice, race, class and gender. From Cancer Alley to Sacrifice Zones, we explore the source of the Environmental Justice/Racism movement. We also interrogate the uneasy peace between the environmental justice and the environmental/conservation movements in terms of race, class and gender. This leads into a lecture on the disproportionate effects of environmental degradation on women as well. It also charts the links between women's welfare and population and between gender equity and sustainability. 8 Readings Bullard, 1994. “Environmental justice for all”. Wright, Bryant and Bullard, 1994. “Coping with Poisons in Cancer Alley”. Return Mid-term Exam 2 and discuss (9) The trade-off between social equity and sustainability in Peru (Coomes) (10) Political economy and ecology: causes of tropical deforestation (Coomes) Nov. 24 Nov. 26 Nov. 29 Reading Johnson, 2000. “Population, food and knowledge”. (11) Poverty, human development and environment (Badami) Dec. 1 To round off this set of lectures, we will address, in the context of the challenges discussed, the following questions: can a world population that could stabilize at around 10-11 billion be provided for, and can we alleviate mass poverty, while preserving our environment? Can human development be attained at moderate per capita resource consumption? What obstacles and challenges might we face, and how might we meet these challenges? What technological, institutional, and economic approaches might we apply to address environmental impacts due to human activity in both rich and poor countries? What can we learn from cross-national and historical comparisons in meeting these challenges? Readings Dasgupta, 1995. “Population, poverty and the local environment”. Smil, 1993. “Effective Strategies”. Wrap-up, review for Final Exam Dec. 3