MGRS - Southwest Research Institute

Comments by Clark Chapman

CHAPTER 6: MOUNT GRAHAM RED SQUIRREL

If you equate the Earth’s 4.5 billion-year history with a single year, the end of the last Ice Age – some 11,000 years ago – occurs one minute and 17 seconds before the clock strikes midnight on December 31. At this point in our very recent past, when condors were feasting on the remains of North American sloths and elephants, the topography of Southeastern Arizona had the same contours it has today. A dozen or so mountain ranges jutted up into the sky. In between were broad valleys filled with eroded material that had washed down from the surrounding peaks. Today, these flatlands are home to cacti and creosote. Back then, the basins held shallow lakes lined with spruce, fir, pine and aspen trees. The tree squirrels that lived in these Ice Age forests had barely changed in appearance for several million years, leading modern biologists to call them

“living fossils.” One type of tree squirrel with a hint of red in its coat scampered around the forest floor in a perpetual search for food to support its hyperactive metabolism and a heart beating hundreds of times per minute. This 8-ounce squirrel scampered into the branches above to rip the scales off cones that had dropped from the coniferous trees, spinning them like cobs of corn in order to devour the calorie-rich seeds within.

As the planet began to warm up at the end of the last Ice Age and the glaciers started to recede to the poles, the vegetation in Southeast Arizona migrated both northward and toward the sky. Spruce and fir trees that were once able to survive in valleys along the current U.S.-Mexico border only found a suitable combination of temperature and rainfall near modern day Canada or at the very top of the Southwest’s tallest mountains. As the vegetation shifted, so did the squirrels. Once able to roam across much of the region, the red squirrels in Arizona and New Mexico were now stranded atop a handful of ranges like shipwrecked sailors. Unable to cross the intervening desert seas, the squirrels reproduced and evolved in isolation on these forested “sky islands,” their demeanor and DNA drifting from the appearance and genetic makeup of other nearby populations. Thousands of years later, the divergence in the beaks of finches living on

1

another set of islands, the Galápagos, would help Charles Darwin and others develop the theory of natural selection that guides modern biology.

The only sky island in the Southwest with any red squirrels left is 10,720-foot

Mount Graham, located about 75 miles northeast of Tucson. Soaring nearly 7,000 feet up from the desert in a matter of a few miles, Southern Arizona’s tallest range – and one of the Southwest’s steepest – is a jewel of biodiversity. Graham is home to some 900 types of plants, several found nowhere else, and it is believed to have a richer collection of species than any similarly sized mountain on the continent.

Biologists aren’t the only scientists who prize Mount Graham. The range is equally important to astronomers because it is one of the best places on the planet to build a telescope. The rarefied air above Mount Graham’s summit is relatively free of dust, clouds and water vapor, affording astronomers a sparkling view of the heavens. Similar conditions are found elsewhere on mountaintops in the Southwest, Hawaii and Northern

Chile’s Atacama Desert, but many prospective sites are either too snowy, spoiled by light pollution, too far from civilization, not open to development or so high that astronomers would need to wear oxygen masks. In the 1980s, a consortium of astronomers led by the

University of Arizona and the Smithsonian Institution began to zero in on Mount Graham as they searched for a location to build the first in new class of telescopes – an instrument able to peer so deep into universe and so far back in time that scientists could nearly see the Big Bang, some 14 billion years ago. It looked like Mount Graham would fit the bill and help usher in a golden age for astronomy. Managed as a national forest and surrounded by vacant public land, the range was still topped by dark skies and it only took three hours to drive from UA to the summit on an existing road that was paved almost the whole way. Other sky islands in Southern Arizona, most managed by the

Forest Service under the “multiple use” doctrine, already had observatories on top, so

Mount Graham seemed like the logical place to build a $200 million telescope complex

[The logic of this sentence isn’t totally clear to me. I don’t think you mean that because other observatories were on other mountains, there was no room for further development.

I think you are saying that the earlier observatories provided precedence. But the real

2

reason is that astronomers have, for many decades, been looking for the best sites around the world. Mountains with relatively clear weather are those sites. Then the would-be telescope projects need to address practical issues, and ownership is one of those]. The project would solidify the school’s position as a global leader in astronomy, bolster

Tucson’s bid to become “Optics Valley” and help scientists better understand the birth of galaxies, stars, planets, even life itself.

What stood in the astronomers’ way [I expect you address this later, but you should probably say “Arizona astronomers’ way” because the selection of Mt. Graham was a competition. The LBT’s website says that 280 different mountain-tops around the world were considered. I don’t know if that is right, but there were promoters for putting this project on several other mountains. While one might ideally hope that Mt. Graham was selected because it was objectively the best site, I think that is highly questionable. I think that a lot of politics was involved. Certainly astronomers at the Univ. of Hawaii were not striving to take-over the red squirrel habitat on Mt. Graham] was the Mount

Graham red squirrel, the Ice Age relict that had held on atop the range as the planet warmed. The rodent inherited the snail darter’s mantle as a charisma-challenged impediment to human “progress” by inspiring a new breed of activists to obstruct development they disliked by exploiting the Endangered Species Act’s strict protections.

In the two decades of tortured politics surrounding the squirrels versus scopes battle, we not only see environmentalists making hyperbolic claims to block a project that offended their sensibilities, but also crystal clear evidence of lawmakers and political appointees acting at the behest of UA as they squashed the recommendations of federal biologists.

The tempestuous fight for control of a mountaintop prized for its clear skies can blind us to the overarching and perhaps insoluble problem confronting Mount Graham’s squirrels: climate change. It was a natural epoch of global warming that put the squirrel in a precarious position some 11,000 years ago, and it is human-induced global warming that now threatens to finish off the remnant population. Our modern-day tampering with the planet’s weather may have helped set the stage for an insect outbreak in the 1990s that damaged thousands of acres of squirrel habitat and primed the creature’s home for an

3

inferno in 2004 during a drought that may have also been related to climate change. The bugs and the fire have had a far greater impact on the squirrels than the 9-acre telescope site. As temperatures continue to rise in the 21 st century – this time due to the carbon coming out of tailpipes and smokestacks around the globe, not just the climate’s natural ebb and flow – the Southwest’s vegetation is likely to keep shifting northward and upslope, just as it did at the end of the last Ice Age [Do you know that this is true? I don’t know myself, but I’m sure you do realize that models for the effects of global warming do not predict uniform warming everywhere. I think I’ve heard that one effect of global warming may be to enhance the warming of the eastern Pacific Ocean, which produces El Nino. And El Nino episodes often involve colder and wetter winters in the

American Southwest as the jet-stream moves southward, like we’re having now. I could imagine that the red squirrels habitat might even be favored by global warming.]. There are only about 200 red squirrels left on Mount Graham and at some point in the not too distant future, there might not be enough forest left around the telescopes for the subspecies to survive.

Mount Graham’s red squirrels were in jeopardy long before Anglos settled the

Southwest and humans began to change the earth’s climate. Since the last Ice Age, the squirrels have been trapped on a single mountain that is prone to wildfires and able to support no more than 1,000 of their kind. The outlook is similarly grim for other endangered species that are relicts of the Ice Age, such as desert pupfish that once lived in prehistoric lakes but now occupy a handful of pools and springs surrounded by thousands of square miles of bone-dry land. Stranded on forested sky islands and confined to water holes in the middle of desert oceans [I think “oceans” has the wrong connotation here], these species will probably never lose their endangered status, not because the ESA is ineffective, but because of their immutable natural history. Even with a relatively static climate, these inherently vulnerable creatures might succumb to disease or natural disaster. Now, with our hand on the planet’s thermostat, species like the Mount

Graham red squirrel serve as omens for what may befall the rest of creation. While the

ESA can do nothing to stop global warming, proper application of the law can better insulate endangered species against the changes to come.

4

* * *

When some of the nation’s top forestry experts got together in February 2005 to talk about climate change, they didn’t waste any time debating whether the planet was getting warmer. In the conference room of the Sedona Hilton there was no back and forth about what share of the warming was due to emissions or natural variation. The accepted assumption was that the biggest climate shift since the end of the last Ice Age was under way. [This was confirmed on 2/2/07 by the latest IPCC report: http://www.ipcc.ch/SPM2feb07.pdf

. Glancing at the maps in this report, it looks as though southern Arizona is expected to get warmer, and – in some seasons – drier over the next century.] The question was how it would play out in the West’s forests and woodlands. So gloomy were the answers that many of the speakers felt obligated to apologize after their PowerPoint presentations.

The meeting began with an overview of the problem from Jonathan Overpeck, director of UA’s Institute for the Study of Planet Earth and a lead author for the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The IPCC, formed in 1988 by the United

Nations and World Meteorological Organization, is considered by many to be the most authoritative scientific voice on global warming. Overpeck told the crowd that computer models predict temperatures in the Southwest could rise 14, even 20 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the 21st century (in the 20 th century, the planet’s average temperature only rose about 1 degree). “Do I believe we’ll see a rise of 20 degrees?” Overpeck said. “No,

I wouldn’t put a lot of money on that, but I would put a lot of money on 10 degrees. It’s not going to be just a couple of degrees.”

While virtually all climate experts agree the Southwest and the rest of the planet will get hotter this century, the outlook for precipitation in the region is ambiguous. Some models suggest it’ll be drier; others predict it’ll be wetter; most experts believe the droughts and wet spells will become more extreme. Projections for atmospheric moisture are especially hazy in the Southwest because precipitation in the region is governed by two very different patterns. In Tucson, for example, the average annual rainfall of 12

5

inches is divided almost evenly between winter storms coming in from the Pacific and the summer monsoon, when a high pressure system sets up around the Four Corners and pulls moisture into the region from the south and east to produce violent thunderstorms.

Even though climate change may increase annual rainfall in the Southwest, many scientists at the meeting predicted global warming will reduce the region’s water supply.

Any additional rainfall may vanish as rising temperatures increase evaporation rates, while more vigorous plant growth will suck up more soil moisture. And because the mercury is projected to climb most in winter, more rain than snow will fall in the high country, thinning the snowpack that provides the vast majority of water in Western rivers, reservoirs and even many groundwater basins.

Even slight changes in temperature could have dramatic effects on the West’s vegetation and there was considerable evidence global warming is already making insect outbreaks and wildfires more common in the region. The region’s flora is so vulnerable because its deserts, savannahs, woodlands and coniferous forests lie so close together – in some cases, like Mount Graham, all of the plant communities are found in a single range.

To illustrate the issue, Ron Neilson, a bioclimatologist with the U.S. Forest Service, used the example of the Mogollon Rim, the escarpment that runs by Sedona’s red rock mesas and separates the saguaro cacti in Phoenix from the ponderosa pines around Flagstaff.

The Mogollon Rim, which stretches across central Arizona and west-central New

Mexico, is the topographical feature that the Rodeo-Chediski Fire took advantage of in

2002. When you drive north on I-17 from Phoenix to Flagstaff, the vegetation is so different below and above the Rim because only the higher-elevation terrain to the north sees freezing temperatures for more than 24 hours straight. “We’re subtropical in

Southern Arizona and temperate in Northern Arizona. What differentiates it is the hard frost,” Neilson said. “It doesn't take much imagination or much warming to see how that frost level will shift over that elevational scarp and rocket to the north.” In Northern

Arizona, the vegetation might convert to the brushy chaparral found along the California coast. On Mount Graham, desert plants could shift skyward and squeeze out the top layers of forest that the red squirrel depends on. The unique flora and fauna in national parks across the globe may migrate toward the poles and into less protected settings.

6

Exactly how the vegetation will move is anyone’s guess, because hotter temperatures may be accompanied by drier or wetter weather.

Uncertainty is unavoidable when you reduce the planet’s climate to a simulation in a supercomputer, but scientists need only observe today’s forests to record how global warming may be starting to alter ecosystems. Unprecedented insect outbreaks are one of the most troubling developments. In 1957, a cub reporter for the Santa Fe New Mexican named Tony Hillerman was writing about insects killing a million acres of piñon and ponderosa pine in the region. The trees succumbed to one of the worst droughts in centuries, according to Tom Swetnam, director of UA’s Laboratory of Tree-Ring

Research, but far more forest was damaged at the turn of the 21 st century during a less severe dry spell. By the end of 2003, there were 3.5 million acres of dead and dying piñon pine in the Four Corners region and 2 million acres of ponderosa pine affected by bugs. It’s possible, Swetnam said, that increasing temperatures are giving insects a leg up they didn't have in the 1950s.

Michael Wagner, a professor of forest entomology at Northern Arizona

University, was even more convinced that global warming was altering insect behavior.

“We're seeing new outbreaks we’ve never seen before, and we're seeing greater severity than we have in the past,” he said. “Even a single season of unusual weather can have a dramatic effect.” The spruce aphid, a native of Germany, had been confined to the maritime forests of the Pacific Northwest for decades but it’s now common in the

Southwest. “This is an exotic species that’s come in during the last eight or nine years and caused major mortality,” he said. “It’s probably related to wintertime temperatures since it does most of its feeding in winter.” The spruce aphid was one of several insects that went to work atop Mount Graham in the 1990s. By the end of the decade, nearly every spruce tree atop the mountain was dead. “Mount Graham is a bit of a microcosm of what we're seeing elsewhere in the Western U.S.,” Swetnam told me. “There's a synergism of disturbances going on up there with the drought, beetles and fire hazards all combined in one place.”

7

Many scientists believe global warming will increase the frequency of fires like

Rodeo-Chediski, Bullock and Aspen, even if the nation starts to thin overgrown forests.

In August 2006, Swetnam and other researchers reported in the journal Science that

“large wildfire activity increased suddenly and markedly” starting in the mid-1980s and most of the change was due to a warming climate, rather than misguided fire suppression

[I thought it was due to misguided arsonists, including Forest Service rangers, like the one who purposefully set the worst fire in Colorado’s history a few years ago; she’s now in jail.]. The scientists looked at 1,116 large blazes that broke out between 1970 and

2003. Compared to the 1970 to 1986 period, wildfires in the more recent era were four times as frequent and burned 6.5 times the acreage. The length of the wildfire season increased an average of 78 days. The most dramatic increases in fire activity transpired in the Northern Rockies, where warmer temperatures led to a thinner snowpack that melted earlier in spring and led to more flammable conditions in summer. The kicker: more forest fires around the globe may exacerbate the problem of global warming because their smoke plumes will emit even more heat-trapping greenhouse gases.

Swetnam and many of the other scientists at the 2005 meeting in Sedona were in

San Diego a year-and-a-half later for the annual meeting of the Association for Fire

Ecology, which produced a consensus declaration on global warming’s connection to wildfires. The scientists argued that shifts in vegetation caused by warmer temperatures and new precipitation patterns will only be compounded by the increased fire activity.

“For example,” their declaration said, “temperate dry forest could be converted to grasslands or moist tropical forest could be converted to dry woodlands. Following uncharacteristically high-severity fires, seedling reestablishment could be hindered by new and unsuitable climates. Plant and animal species already vulnerable due to human activities may be put at greater risk of extinction as their traditional habitat become irreversibly modified by severe fire.”

***

I’ve gained some insight into Mount Graham’s ecology, its history and its red squirrels by backpacking down the Ash Creek Trail. The path begins about 1,000 feet

8

lower than Mount Graham’s summit and around one mile west of the telescope complex.

The trail then follows the gurgling creek down the shady, north face of the range, plummeting 6,300 feet in nine miles, so the ache in your knees while going down matches the pain in your lungs while hiking back up.

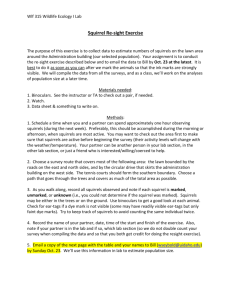

As you journey downhill on the Ash Creek Trail, you slice through a pyramidshaped layer cake of ecological zones, as shown in Figure 1. At the trailhead, around

9,500 feet elevation, the forest is in a transition between the top two layers. Uphill, there are a couple thousand acres of Engelmann spruce and corkbark fir. While this layer is the smallest, no other mountain in Southern Arizona has such an extensive spruce-fir forest because no other range has so much terrain so high up. This is probably why no other sky island besides Mount Graham still has red squirrels. Immediately downhill from the trailhead, there are about 11,000 acres with a mix of conifers that includes Douglas fir, southwestern white pine, ponderosa pine, plus aspen trees. When the red squirrel was first listed as endangered in 1987, biologists believed the animals were heavily dependent on the top layer, the spruce-fir forest zone, where the telescopes are located. However, subsequent surveys have frequently found the squirrels in the transition zone and the mixed conifer forest, even down to around 7,800 feet elevation. The telescope sites did provide excellent squirrel habitat, but they weren’t as vital to the species as initially believed.

9

Figure 1: Vegetation on Mount Graham

10,720 feet

Spruce-fir forest (squirrel critical habitat)

9,800 feet

Transition zone

9,000 feet

8,500 feet

Mixed-conifer forest

Ponderosa pine forest

6,500 feet

Oak/piñon/juniper woodland

4,500 feet

Desert scrub

3,500 ft

NOTE: Elevations are approximate and vary on north- vs. south-facing slopes

In May 2004, I started hiking down Ash Creek Trail and descended from the transition zone into the mixed-conifer forest. I passed by moss, ferns and mushrooms – welcome sights since Tucson was currently baking under triple-digit heat. In several spots along the trail, I saw the orange plastic flagging that helps biologists locate the piles of debris, known as middens, in which red squirrels cache their food. It was in this canyon in 1894 that scientists collected the specimen that J.A. Allen, curator at the

American Museum of Natural History, used to scientifically describe the Mount Graham red squirrel. The other two-dozen subspecies of red squirrel are found across much of

North America, from Alaska south through the Yukon, down the Rockies, across the upper Midwest and into the Northeast. The squirrels atop Mount Graham look virtually the same as the mongollonensis subspecies along the Mogollon Rim, but more than a century ago Allen thought Mount Graham’s squirrels were distinct enough to warrant classification as a separate type of red squirrel. Other biologists and telescope backers subsequently challenged Allen’s finding, but it was ultimately upheld by genetic studies.

About 1.5 miles down the Ash Creek Trail, I came to a historic mill site with a heavily rusted boiler, evidence of the logging that began on the mountain in the 1880s to

10

supply lumber for the mines and farming towns below. Around the turn of the century, settlers described the red squirrel as common atop Mount Graham, but as logging operations continued up through the 1970s, including considerable clear-cutting, the squirrel’s population declined. Even areas that were logged decades ago are still not suitable for the squirrel because the rodent – like its occasional predator, the threatened

Mexican spotted owl – prefers old-growth forests. In these relatively undisturbed woods, squirrels find an abundance of nest sites and hiding places in downed logs and standing dead snags. The closed canopy above creates a cool, moist microclimate that gives rise to fungi, another food source for squirrels, and prevents the spoilage of pine cones stored in the middens. The interlocking network of branches in an old-growth forest also provides cover from avian predators and runways for retrieving cones.

After another mile or so of hiking downhill, the creek glided over a tilted slab of metamorphic rock that’s so slick equestrians are advised to take a long detour. Soon I could hear 200-foot Ash Creek Falls, the tallest perennial waterfall in Southern Arizona.

At this point, around 8,000 feet elevation, I began to leave the mixed conifers and enter the ponderosa pines, where the woods were noticeably less shady and lush. This forest, which covers tens of thousand of acres on Mount Graham, is not suitable for red squirrels because the animals don’t like to eat ponderosa cones. The woods are also too dry and open, so the change in vegetation provides a downhill barrier as insurmountable as the ocean.

The ponderosa pines, however, are the preferred habitat for the introduced

Abert’s, or tassel-eared squirrel. In the early 1940s, the Arizona Game and Fish

Department sought to bolster varmint hunting on the mountain by relocating some

Abert’s squirrels from the Flagstaff area (until 1986, you could also get a permit from the state to hunt Mount Graham red squirrels). State game officials expected the Abert’s squirrels would remain between 6,000 and 8,000 feet elevation because the animals eat the cambium layer beneath the bark of ponderosas. But the Abert’s squirrel proved adaptable and began migrating upslope into the mixed conifer forest that lies above the ponderosa pines. It’s likely that competition for food from the Abert’s squirrels – plus

11

continued logging on Mount Graham – contributed to the sharp decline in red squirrels by the middle of the 20 th century. By 1966, no red squirrels had been found on Mount

Graham for eight years, leading some biologists to mistakenly conclude the subspecies had blinked out.

Another two miles down the trail I came to Oak Flat, an uncharacteristically level section that makes for a choice camping spot. Now at about 6,000 feet elevation – roughly halfway between Graham’s summit and its base – the ponderosa pines begin to give way to even drier, warmer woodlands with oaks, manzanitas, piñons, junipers and other shrubby plants. I stayed here for the night and retraced my steps the next day. Were

I to have kept descending the trail, the terrain would have become even drier and the vegetation would have grown even more sparse, ending in Chihuahuan Desert with yuccas, prickly pears and mesquite trees. In Thatcher, the town in the shadow of Mount

Graham where I attended the Congressional hearing on the ESA, average annual rainfall is about 10 inches; atop Mount Graham, it’s more than three feet.

The composition of Mount Graham’s layer cake has remained roughly the same for thousands of years, though suppression of fire has radically altered the character of many of the forests over the past century. Up on top, the spruce-fir forest is so cool and wet that fire is an infrequent visitor, even under natural conditions. With the canopy closed and the ground in shadows, very little fuel grows on the forest floor. The needles from spruce and fir trees are also smaller and less flammable than those that fall from the pines lower down the mountain. Like the lodgepole forests of the Yellowstone area, the spruce and fir atop Mount Graham will naturally grow for hundreds of years until a catastrophic fire wipes out the stand and resets the ecological clock. When UA astronomers began to plan their telescope complex atop Mount Graham, the spruce-fir forest surrounding their chosen site hadn’t burned for three centuries and was overdue for a big blaze. “The more and more time that goes on between fires, the more catastrophic and higher intensity the fire will be,” said Henri Grissino-Mayer, a tree ring expert at the

University of Tennessee who extensively studied Mount Graham’s fire history. “If humans don't do something about the fuels, nature will.”

12

Tree-ring studies by Grissino-Mayer, Swetnam and others have revealed that the layers beneath the spruce-fir forest burned frequently prior to the late 19 th century, when overgrazing began to remove the grasses that had carried fires into sky islands from below. “Almost every summer, people could see smoke coming out of at least one or more mountain ranges around Tucson and that’s born out in the old newspaper archives in the Star and Citizen ,” Swetnam said. “In the big years, when it was really dry, all of them would be on fire.” In historic times, the mixed conifers on Mount Graham burned as often as every four years, about as frequently as fire touched the ponderosa pines in the next layer down. Because the mixed-conifer forest burned so often, fuel loads there remained light, so when flames did arrive they usually stayed on the ground. This layer therefore served as a buffer that protected the spruce-fir forest on top of Mount Graham – as fires ascended through the oak woodlands, ponderosa pines, then mixed conifers, they almost never gained enough energy to spark a catastrophic, stand-replacing blaze in the red squirrel’s prime – though not exclusive – habitat near the range’s summit. Eventually, though, that forest would have to burn.

After climbing out of Ash Creek, I went to a Forest Service barn where state, federal and university biologists were preparing for the semi-annual red squirrel survey.

To measure the population, surveyors visit a random sample of middens, the piles of debris in which squirrels will squirrel away their pine cones and other food. Each spring and fall they monitor about one-quarter of the 1,300 known middens – most of them abandoned for years – then extrapolate the results to come up with an estimate of the entire population. My group was assigned the G.P.S. coordinates of a dozen middens, but even with the assistance of satellites it was tough to locate the sites. The thick canopy of the old-growth forest kept interfering with the G.P.S. signals as we bushwhacked through the woods and crossed steep slopes covered by boulders balanced on their angle of repose. As a remedy, the biologists had to pull out the old-fashioned technology of map and compass. Once we arrived at the middens, it was common to see and hear the resident squirrels since they fiercely defend their caches (each midden typically provides a home base for just one squirrel). As we approached the middens, the squirrels bolted up

13

the trees, then started to chatter at us before leaping effortlessly from branch to branch in a forest swaying from a stiff breeze. Even without an actual squirrel sighting, researchers can determine if a midden is active by looking for signs of digging or freshly peeled shells from pine cones. “Everything is centered around their midden,” explained Tim

Snow, a Game and Fish biologist who organized the survey.” The colder temperatures inside the middens prevent the cones from opening up and spilling their seeds – the nutritional nuggets squirrels prize. “If you reach in,” Snow said, “it's like a refrigerator. ”

Cut down too many trees in a forest and the middens are exposed to more desiccating heat. It’s like unplugging the refrigerator: the food spoils.

Tree squirrels are constantly raiding the icebox and demand a continual supply of food because they have an internal motor that’s stuck in high gear throughout the year

(their heart rate ranges from 150 to 450 beats per minute). The squirrels, which do not hibernate in winter, are in a perpetual struggle to turn food into energy because their small bodies lose heat rapidly. As a general rule, smaller animals have more trouble staying warm because heat loss is proportional to an object’s surface area, while heat generation is proportional to an object’s mass (this is why timber wolves in Alaska are double the weight of Mexican wolves in Arizona). Finding and consuming food therefore occupies the largest share of a squirrel’s time. “The greatest single factor to influence the survival of squirrels is probably food availability,” write Michael Steele and John

Koprowski in their 2001 book, North American Tree Squirrels . Koprowski now heads the

Mount Graham red squirrel monitoring project. Cones and other food are abundant in fall, but nearly absent in winter, so a squirrel must store energy in its body as fat and also cache backup supplies of fuel in its midden. “For an animal that is literally walking an energetic tightrope without a net, squirrels are remarkably fit for such a challenge,”

Steele and Koprowski write. Many tree squirrels have hind feet that can rotate 180 degrees to allow them to scamper down trees headfirst. Their big bushy tails help them balance. To escape predators, the squirrels can run up to 17 mph and the

“countershading” of their fur camouflages them from natural enemies. While running on the ground, their darkened back blends in with the forest floor and when scampering in the trees, their light underside causes them to stand out less against the sky above.

14

The thick spruce-fir forest I was bushwhacking through felt primeval. Wind in the pines below sounded like surf on the shores of the sky island. The mud revealed abundant tracks of elk, bear and cougar. It was also impossible to see the telescopes. But even before the observatories were built atop Mount Graham, the range was hardly pristine.

About half the squirrel’s habitat had been lost by the 1970s. The mountaintop was already home to a state highway, plus a maze of dirt roads to support 12,000 acres of logging. There were campgrounds, parking lots, dozens of cabins, a Bible camp, an artificial lake, plus a forest of radio towers atop one of the tallest peaks.

The preceding winter had been relatively wet, so even in late May I found some snow on the shady, north-facing slopes. That moisture would soon be gone as Arizona entered the parched season that precedes the arrival of monsoon thunderstorms, typically around July 4. As the biologists and I lost elevation while searching for more middens, the fuel at our feet grew thicker and crunchier. It didn’t take much imagination for me to envision how flames could capitalize on the chimneylike canyons that were choked with trees wherever the soil could overcome gravity and erosion to maintain its purchase.

“Powder keg” is the phrase the top firefighter for the local ranger district had used to characterize the range. Many foresters describe Mount Graham as having the highest fuel load in the Southwest. Two years before, the 30,563-acre Bullock Fire had nearly wiped out Summerhaven on nearby Mount Lemmon and the next year the 84,750-acre Aspen

Fire had incinerated two-thirds of the 467 homes there, so with the drought wearing on,

Mount Graham and its squirrels seemed to be living on borrowed time. “That's everyone's fear and it's one of the few things that brings people together on the issue,” Koprowski told me a few days after I came down the mountain. “Every time I drive up there, I wonder if this is the last time I'll see the mountain in this condition. All kinds of gloom and doom scenarios keep me up at night.”

* * *

When astronomers sit down to design a telescope they face a fundamental problem: Bigger mirrors allow scientists to peer farther into space and further back in

15

time because they gather more light and bring fainter objects into focus. But the very weight of massive mirrors can cause their reflective surface to bend and warp the celestial light. A solid hunk of glass will also take ages to cool off once the sun goes down and the stars come out. That distorts incoming images because the warmer air above the mirror shimmers – think of the blurry waves of heat rising from a strip of sun-baked asphalt as you look down a desert highway. The problem had stymied astronomers for decades until

University of Arizona astronomer Roger Angel figured out a solution by melting Pyrex cups in his backyard kiln. Angel, a native of Lancashire, England who was educated at

Oxford University and the California Institute of Technology, devised a method for fashioning the glass into a hollow, honeycomb design that simultaneously made the mirror light, strong and well-ventilated. The innovation helped Angel win a $330,000

“genius grant” from the MacArthur Foundation in 1996 and solidified UA’s reputation as a leader in the field of astronomy.

The process has migrated from Angel’s backyard to the Steward Observatory’s cavernous mirror lab beneath the bleachers of UA’s football stadium. To make a honeycomb mirror, technicians first heat a rotating oven to near 2,200 degrees

Fahrenheit. They then melt 20 tons of glass that is made in Japan using white sand from

Florida and boron from Southern California’s Anza-Borrego Desert. The liquid glass cools around 1,800 hexagonal blocks, which are later removed to yield a mirror that’s 80 percent hollow and able to float on water. “It's about as light as balsa wood,” Angel told me during a tour of the facility. It’s unclear how many years of bad luck would ensue if one of the big mirrors cracked because the lab has yet to lose one of its creations.

Gingerly, technicians lift the unfinished mirror and set it down for the crucial next steps: polishing and testing. Month after month, a computer-guided disc buffs atoms off the glass so precisely that if the mirror were as wide as the United States, the biggest imperfection would be less than an inch tall.

Just one super-sized reflector would hold the promise of new astronomical discoveries, but UA astronomers magnified the technology’s potential in the 1980s by proposing a double-barreled telescope that would feature a pair of 27.6-foot-wide

16

mirrors, each costing $12 million. This Large Binocular Telescope, or LBT, would deliver images 10 times as sharp as those produced by the orbiting Hubble Space

Telescope.[This is not quite right. The factor of 10 is due to the mirror diameter alone, due to physics alone. The LBT would, in practice, be less sharp than the ideal due to the atmosphere. Adaptive optics is a technology that permits groundbased telescopes to more closely approach the ideal by lessening the effect of the atmosphere. Hubble has no atmosphere to contend with. So adaptive optics does not contribute to further improving the image sharpness; it restores some or most of the image degradation by the atmosphere. I also don’t understand this “ten times as sharp” number. Resolution of a telescope varies as its aperture whereas light-gathering power varies as the square of the aperture. HST has a 2.4 m primary mirror whereas LBT is somewhat over 11 m, so LBT would be 4 or 5 times as sharp. Of course, in the double-barrelled configuration, the resolution is sharper in one dimension than the other. The light-gathering power is superior to HST by about a factor of 25.] The LBT would also take advantage of another technology pioneered at UA – adaptive optics – that corrects for turbulence in the skies above. Even in the thin air atop Mount Graham, there is still plenty of atmosphere between the mirror and the stars than can blur images. To cancel out the aberrations, hundreds of tiny electro-magnetic actuators would bend the mirror thousands of times per second and distort its surface, nanometer by nanometer, so that celestial objects remain in focus.

To Angel and other astronomers, the LBT would be the first of a new generation of observatories, an instrument that could shift paradigms and unlock existential mysteries. In the 17th century, shortly after the invention of the telescope, Galileo had used his own device to discover four new moons surrounding Jupiter and jettison the belief that the universe revolved around the Earth. In the early 20th century, Edwin

Hubble used a new 8-foot-wide mirror atop Mount Wilson in Southern California to propose the concept of an expanding universe. With the LBT, astronomers would be able to peer 90 percent of the way back to the Big Bang and gather light that began its journey toward Earth 12 billion years ago. No other instrument would be more valuable in the search for planets harboring life, one of Angel’s other areas of research. “What's

17

incredible about astronomy,” Angel told me, “is that here we are at the beginning of the

21st century and there are still huge unknowns out there. We don't know what most of the matter is in the universe. We don't know whether there is life anywhere else . . . We're not just dotting the I's and crossing the T's. We're uncovering vast areas of ignorance.”

Telescope opponents believe UA astronomers oversold the astronomical value of

Mount Graham and claim the site will be bedeviled by cloud cover and air turbulence. A

2-year study by the National Optical Astronomy Observatory did find that the view from

Graham’s summit was inferior to the vantage atop Hawaii’s Mauna Kea – the dormant volcano whose lower [above 11,000 feet, Mauna Kea is not vegetated...it is like the moon. Wild pig hunters have objected to the Mauna Kea Observatory as well as natives who regard it as sacred] forested slopes are home to the endangered palila bird that has figured prominently in ESA court cases. UA scientists counter that observations from the scopes on Mount Graham have already proved it is a world-class location for astronomy.

“Sure, I can think of better sites,” said Peter Strittmatter, director of UA's Steward

Observatory. "My favorite is the moon. There's no clouds and there's no air, so there's no turbulence. The only problem with the moon is, it's kind of expensive to get there."

[There is no question that Mauna Kea, and probably other very remote sites, are superior to Mt. Graham. Mt. Graham is a good but not great site. It is practically useless in July and August. The relative proximity to Tucson is a major advantage, especially for

Arizona astronomers.]

As UA astronomers performed optical tests on Mount Graham in the early 1980s, state and federal biologists conducted more wildlife surveys atop the range. The results of the two inquiries would soon put the telescopes and the squirrels on a collision course, and drive a wedge between most of the school’s astronomers and nearly all of the region’s environmentalists – two groups who put faith in science, believe in conserving dark skies and tend to be liberal in their politics. In 1982, Fish and Wildlife ruled that the squirrel might deserve federal listing, pending further studies, and two years later UA gave the Forest Service its proposal for a telescope complex with up to 18 instruments on

Mount Graham. When Congress passed the Arizona Wilderness Act in 1984, the Forest

18

Service declared 3,500 acres atop the range as a potential observatory site. Environmental studies related to the telescope proposal further convinced biologists that the red squirrel was imperiled, even without construction of the observatories. The Arizona Game and

Fish Department, a frequent foe of hard-line environmentalists since it often caters to the demands of the hook-and-bullet crowd, suggested that the squirrel be listed as endangered in 1985, an era when activists had yet to grasp the power of petitions. At the time, biologists estimated there were around 300 squirrels left.

With the squirrel on the verge of being declared an endangered species, UA officials pushed for the creation of a habitat conservation plan in lieu of listing, but that bid failed. In retrospect, such a deal may have produced the most satisfying outcome for astronomers and environmentalists by facilitating the telescope project while also preserving squirrel habitat – and doing so without two decades of lawsuits and civil disobedience. Such conservation plans, however, were uncommon back then and seen by anti-scope activists as creating loopholes in the ESA. After lengthy delays and under the threat of litigation, Fish and Wildlife finally listed the squirrel as endangered in June

1987. The notice in the Federal Register made no mention of global warming or insect outbreaks, and included just one passing reference to wildfires – a reminder that biologists are sometimes clueless about threats to a species when it is listed.

Because of the squirrel’s listing, UA’s telescope plans would have to pass through the ESA’s fine filter. Fish and Wildlife biologists looked at UA’s proposal to build seven telescopes atop the two tallest peaks on Mount Graham – High and Emerald – and concluded that the tree-cutting and increased, year-round human activity would jeopardize the squirrel’s continued existence. As required by the ESA, Fish and

Wildlife’s August 1987 draft biological opinion offered two “reasonable and prudent alternatives”: move the project off the mountain entirely, or restrict it to a relatively degraded portion of High Peak, leaving the more pristine Emerald Peak untouched. That wasn’t acceptable to UA astronomers, so school officials pressured the regional directors of the Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife. In June 1988, Fish and Wildlife biologist

Leslie Fitzpatrick was ordered by her supervisors to create a third alternative: allow three

19

telescopes on nine acres of Emerald Peak, a site she and other government biologists had said couldn’t withstand any new development. Although the footprint of the complex was only nine acres, biologists estimated that a total 47 acres of squirrel habitat would be rendered unsuitable since the forest adjoining the clearing would become too dry and open. As part of this third alternative, the Forest Service would close and reforest a road leading up to High Peak (though return of the spruce-fir forest could take centuries). The

Coronado National Forest would also bar the public from the upper reaches of Mount

Graham and the UA would fund an extensive monitoring program for the squirrels. The third alternative also left open the possibility of four more telescopes on 15 additional acres on Emerald Peak if UA could prove the first three hadn’t harmed the squirrel.

When investigators with the non-partisan Government Accounting Office (now

Government Accountability Office) looked into the allegations of political interference with the biological opinion, they found solid proof that it had occurred. Fitzpatrick told the GAO that her supervisor informed her that if the biological opinion didn’t include a third alternative that allowed for telescopes on Emerald Peak, the document would be prepared by another office. “In a biologically based biological opinion,” Fitzpatrick would later tell Congress, “the Emerald Peak alternative would not have appeared.” A number of studies prior to the 1988 biological opinion, including the draft document, had concluded that development on Emerald Peak posed an unacceptable risk to the squirrel’s survival. A 1985 Arizona Game and Fish Department study recommended that no habitat be modified in the mountaintop area where the telescopes were planned. Fish and

Wildlife itself had argued in the draft that the squirrel was so imperiled that “the loss of even a few acres could be critical to the survival and recovery of this species.”

Fish and Wildlife’s Regional Director, Michael Spear, told the GAO he wasn’t convinced by those studies. Instead, Spear said he considered other factors, such as the need to make an expeditious decision, pressure from UA officials, his belief the school would probably win in court and his favorable view of the telescopes’ scientific value.

“He said the challenge of the Endangered Species Act is to devise compromises that accommodate both needed projects and endangered species,” the GAO reported. As a

20

political matter, that may be true, but on legal grounds Spear was running afoul of the

ESA, which says only the God Squad [what’s that?] is supposed to perform such balancing acts. The GAO report, performed at the request of Arizona’s two senators,

Republican John McCain and Democrat Dennis DeConcini, concluded that the federal government “would have had difficulty in demonstrating to a court” that the third alternative passed muster with the ESA. “The alternative is not supported by prior biological studies of Mt. Graham,” the GAO said. “These studies indicated that any development on Emerald Peak posed an unacceptable risk to the red squirrel’s survival.”

The GAO had found similar tampering with scientists’ findings the year before in the government’s refusal to list the Northern spotted owl. Investigators concluded that a

Fish and Wildlife Regional Director in Portland, Oregon had also considered nonbiological factors as he bowed to pressure from headquarters. In response to a listing petition from environmentalists, Fish and Wildlife officials had asked scientists to review the owl’s status. They then took hold of the biologists’ report and rewrote the science by including more information from the timber industry and removing the pessimistic assessment of Forest Service timber policies. “The revision had the effect of changing the report from one that emphasized the dangers facing the owl to one that could more easily support denying the listing petition,” the GAO found. “None of the changes made subsequent to the [initial] draft were peer reviewed, even though they contradicted and replaced information that had been endorsed by outside spotted owl experts.”

Environmentalists went to court over Fish and Wildlife’s decision not to list the spotted owl, a federal judge agreed that it was “arbitrary and capricious” and the bird was eventually declared threatened after the God Squad was convened. Even though the GAO had found just as much evidence of political shenanigans with the biological opinion for the Mount Graham telescopes, by the time the GAO released its report, in June 1990, construction on Emerald Peak was a fait accompli . Two years before, UA officials decided that Congress should write the project into law, rather than have it dissected by more biological studies. To convince lawmakers to go along with the plan, UA paid more than $1 million to the swank D.C. lobbying firm of Patton, Boggs and Blow (the money

21

came from a taxpayer-funded federal research grant [this statement should be backed up; if it is true, as I strongly doubt, people should be in jail]). DeConcini, Arizona’s

Democratic senator, tacked a special provision sanctioning the Mount Graham project onto a land-exchange bill known as Arizona-Idaho Conservation Act. The rider passed a week later, on the last day of the 100th Congress, without any public hearings.

Environmentalists decried the sneak attack as the most significant undermining of the

ESA since the Tellico Dam case a decade earlier.

UA’s collusion with top officials in Congress, the Forest Service and Fish and

Wildlife produced a legislative victory in 1988, but the strong-arm tactics enraged many on campus and the schools’ seeming disregard for the rule of law hardened opponents’ resolve to stop the project by any means necessary. Just a few weeks before the rider passed in 1988, Dave Foreman, a founder of the Earth First! radical environmental group, vowed that like-minded activists would destroy the telescopes. “There are people who are prepared to make them put the scopes up there several times – which means a telescope doesn’t see the stars very well if its mirror is broken,” he told Jim Erickson of the Arizona

Daily Star . “It’s certainly not something I would do myself, but anybody with any sense has to realize that’s something that will happen.” As Erickson pointed out, Foreman had already written a 1985 manual on sabotage, Ecodefense: A Field Guide to

Monkeywrenching.

The 185-page illustrated manual teaches readers how make stink bombs, destroy billboards, and spike trees with metal that can ruin saws (and potentially injure lumberjacks). The book advised embedding trees with ceramic rods to avoid metal detectors, though the practice of tree-spiking was renounced in 1990 by Earth First! leaders protesting logging of redwood forests in Northern California.

It’s unclear if Earth First! did spike trees on Mount Graham, but they and other anti-scope activists surely tried just about everything else to impede the construction and make UA astronomers’ lives miserable. They shot out a window at the Steward

Observatory, mailed a dead squirrel to its director, they plastered the campus with “No scopes” bumper stickers, they stormed the UA administration building and fought with police clad in riot gear, they locked themselves to the cattle guards in the road that

22

corkscrews up Mount Graham, they spray painted equipment at the observatory site with obscene graffiti, they put an abrasive compound inside a snowblower and front-end loader, they clogged locks with super-glue, they camped out in trees slated for cutting and they robbed $20,000 worth of electronic equipment from the mountain. The Tucson

Police Department tried to infiltrate Earth First! with an agent provocateur , but the instigator blew his own cover in 1992 during a Columbus Day protest on campus. After the portly policeman-cum–protestor and his ostensible allies charged into the offices of the Steward Observatory, the long-haired cop-in-disguise accidentally dropped his 9millimeter semiautomatic pistol on the floor. After flashing his badge and identifying himself as a police officer, the nark slunk out of the building. When it came time for the

UA to truck a $1 million mirror from the campus to Mount Graham for installation in a telescope sponsored by the Vatican, the highway patrol provided an armed escort and closed off the overpasses on I-10 so saboteurs couldn’t use them as platforms for launching attacks. During a Earth First! rally on the mountain, the state Department of

Public Safety deployed a phalanx of 96 officers wearing helmets and shields to defend the two observatories that had already been built, costing taxpayers $208,304.

UA only generated more animosity in 1993, when it moved the site of the LBT slightly outside the congressionally designated 9-acre footprint – from 600 feet to the west of the other two telescopes to 600 feet east of the instruments. Fish and Wildlife initially balked at this move – even though it appeared that the trees would be cut in a less valuable area for squirrels and in a better place for viewing the heavens – then the agency suddenly reversed itself. In the first week of December, an acting state director OK’d the switch without any public hearings or chances for environmentalists to appeal. On

December 6, the Forest Service assented to the decision and the next day, on the 52 nd anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 250 old-growth trees were felled on less than an acre on Emerald Peak so engineers could drill test holes in the ground.

Although the forest was cleared before any activists could ensconce themselves in the trees, UA’s seeming subterfuge prompted even more lawsuits that delayed the LBT’s construction for several more years. It would take another rider, this time a one-sentence provision attached to a $160 billion spending bill signed by President Clinton in April

23

1996, to finally sanction the LBT. UA had prevailed, but as the project neared completion it lacked the moral support and financial backing of many academic powerhouses stung by the controversy, including Harvard, Cal Tech and the University of Chicago. In 2001, with the centerpiece LBT under construction, vandals used sledgehammers and crowbars to do $200,000 worth of damage to vehicles, construction equipment and the underground powerline feeding the site.

In addition to hyping the project’s threat to the Mount Graham red squirrel, antiscope activists also enlisted Native Americans in their cause. Some Apache Indians claimed Graham was sacred to them and said the telescope project was blasphemous.

Franklin Stanley, a spiritual leader of the San Carlos Apache tribe, equated Graham with an altar and said UA’s project was akin to “taking an arm and a leg off the Apache.”

Apaches’ complaints opened up new avenues for litigation and added an air of cultural imperialism to the UA’s plans, but the claims of the indigenous may have been disingenuous. “The mountain itself was subject to only the most casual and ephemeral use by the tribe, as documentary and archeological evidence clearly shows,” wrote

Charles Polzen, curator of ethnohistory at the Arizona State Museum in Tucson. “The reality is that no Apache bothered to take up this cause until non-Indians coaxed certain long-term political dissidents to block construction of the telescope.” At a public forum in 1992, the chairman of the San Carlos Apaches from 1974 to 1978 and 1980 to 1991, discounted Graham’s importance to the tribe. “To be blunt,” former chairman Butch

Kitcheyan said, “I can safely say, with the support of my elders and the medicine people of the tribe, that there’s absolutely no religious or sacred significance to Mount Graham.”

[One has to be skeptical of such testimony. There is a history of conflict within Native

American communities about whether to oppose telescopes, for spiritual and other reasons, or to support them because of the jobs they create, the opportunities for bringing tourists to the local areas, etc.] The next year, Kitcheyan spoke in favor of the project at the dedication for the first two telescopes, just a week after he’d been indicted in federal court on embezzlement charges (in 1994 he was sentenced to 6 months in prison for

24

stealing more than $63,000 from his tribe). Subsequent research has established that

Mount Graham was, in fact, important to at least some Apaches as a prayer site, home to spirits and source of medicinal plants. In 2002, it was made eligible for listing on the

National Register of Historic Places, which would force federal officials to consult with the tribe on future projects in the range.

The civil disobedience by Apaches and Earth First! made for engaging political theater and exciting newspaper copy. But it probably backfired by making the public even less sympathetic toward the activists’ goals atop Mount Graham and the ESA itself

As the controversy was starting to heat up, a 1987 poll of Tucson-area registered votes commissioned by telescope supporters found that 62 percent supported construction of the telescopes, but a majority didn’t want to see any logging or a ski resort atop Mount

Graham. Nine years later, when the LBT’s construction was stalled by litigation, another astronomer-funded survey found that about three-quarters of Tucsonans (and about the same percentage in the much more conservative Phoenix area) favored completion of the project and an equal percentage said “building a telescope and an observatory on Mount

Graham is an appropriate use of public land.”

The mountaintop fight drew national media attention that generally played into the hands of ESA opponents at a time when the act was under assault. In 1990, when the

Northern spotted owl was proposed for listing and preemptive logging restrictions were already roiling the Pacific Northwest, the first President Bush’s Interior Secretary,

Manuel Lujan, Jr. responded to the Mount Graham controversy by asking “Do we have to save every subspecies?” “The red squirrel is the best example,” Lujan said. “Nobody’s told me the difference between a red squirrel, a black one or a brown one.” Describing the ESA as “too tough,” Lujan called for injecting economic considerations into endangered species policymaking and encouraged Congress to weaken the law.

To telescope opponents, the case of the Mount Graham red squirrel may have exemplified how political appointees favor economic expediency over ecological

25

integrity. To ESA critics and many opinion leaders, the fight illustrated how endangered species were being used as surrogates to carry out a left-wing agenda. Shortly after

Lujan’s comments in 1990, the liberal editorial page of the New York Times said environmentalists fighting the Mount Graham telescopes were on the “wrong side of a silly debate.” “There is an unattractive absolutism in the environmentalists’ arguments,” the Times said. “To invoke this helpful act in frivolous causes is to invite its demise.” Six days earlier, the conservative Wall Street Journal had cited activists’ “holy war on

Arizona’s Mount Graham” as an example of the ESA’s excesses. “The law shouldn’t make absolute protection a form of worship if the same animals are found elsewhere, have many subspecies or can be relocated,” the Journal said. Even the ESA’s architects –

Michigan Congressman John Dingell and his chief counsel Frank Potter – had recognized early on that the ESA’s far-reaching provisions could create a backlash. “They may even reach too far,” they wrote in 1978. “If they were to be used in the wrong case, to impose actions which would offend the wrong court, the clear mandate of the statute could well precipitate a repeal of this statutory language through overwhelming pressure upon

Congress.”

Telescope opponents were right that bureaucrats had trumped biologists in approving the construction on Emerald Peak and they were justifiably outraged that

Congress had done the bidding of the UA by circumventing the nation’s premiere environmental law. Still, as opponents’ rhetoric grew more heated, the needs of the squirrel were sometimes subsumed to a messianic campaign against the observatories and their sponsors. “It’s not biology,” one UA graduate student and squirrel expert said about her fellow telescope opponents when interviewed by the New York Times in 1990. “It’s esthetics. They’re tired of all these white things on the tops of mountains. Pretty much the only legal way they’ve got to save an area from development is to find an endangered species and it looks like they’ve got one.”

The fight atop Mount Graham would influence a generation of conservationists in the Southwest. Many leaders of the Center for Biological Diversity and other powerful environmental groups in the region cut their eyeteeth defending the red squirrel,

26

sometimes while allied with Earth First! The controversy also taught practitioners of conservation biology – a field described as a “crisis discipline” by one its founders,

Michael Soulé – that ignoring the political environment could render their science academic. Writing in the journal Conservation Biology in 1994, Peter Warshall, the UA scientist in charge of the 1986 environmental impact statement on Mount Graham, argued that “good conservation biologists must be part lawyer, part teacher, and part biogladiator as well as scientist.”

When biologists approach a policy issue with an agenda, it raises serious questions about whether they’re abiding by objectivity of the scientific method. And one wonders if someone who devotes their professional life to an obscure creature can really be regarded as an honest broker of information on that species. But with UA scientists also stretching the truth and sometimes lying outright, it was probably impossible for any biologist working on the issue to examine the situation dispassionately. In 1995, Michael

Cusanovich, a biochemist who served as vice president for research at UA during the height of the controversy, told High Country News that “we’re in the age of factoids, pseudoscience and Luddites.” In the preceding paragraph, he proved his own point by asking “Is using 8.6 acres in a forest of 400,000 acres appropriate land use?” Mount

Graham encompasses no more than 250,000 acres and nearly all of the range is too low in elevation to be described as a forest. In total, Graham has about 12,000 acres of suitable red squirrel habitat, and some of that is marginal.

At least a few biologists who looked at the effect of the Emerald Peak alternative that Congress had mandated thought it provided a net benefit for Mount Graham’s red squirrels. One of those scientists was Conrad Istock, chairman of UA’s Department of

Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. To Istock, who received a death threat in the mail in return for supporting the telescope project, the squirrel certainly exemplified the ecological costs of human development: inherently at risk due to its isolation on a single mountain, the subspecies had also suffered from decades of logging, grazing, camping, snowmobiling, road construction, cabin building and Christmas tree cutting, even legal hunting until 1986. But for a species that had already survived the destruction of some

27

11,000 acres of its habitat, the loss of another couple dozen acres to telescopes was a minor insult, especially since the project was predicated on a number of conservation measures. There would never again be logging on the mountain (though others feel that by the 1980s it was no longer economical to harvest timber in the rugged range). The

Forest Service would cancel plans to build recreational sites and communications towers.

And the public would be barred from a 1,700-acre squirrel refugium around Mount

Graham’s summit. The upshot, according to Istock, was that Mount Graham had “greater protection, and a more concerted effort at ecosystem restoration, than any of the other

Southwestern mountain islands.” What’s more, the UA was obligated to fund a $200,000a-year monitoring program, which revealed that some of the initial assumptions about the squirrel were wrong: the rodents don’t, in fact, depend on the spruce-fir layer at the very top of the mountain where the telescopes are located and can do quite well in the transition zone and mixed conifer forest below.

* * *

The red squirrel’s ability to survive below the spruce-fir level was turned into a biological imperative in the late 1990s, after the protests and legal fight against the scopes had all but ended. Starting in 1992, a cascade of insect infestations began to ravage the forest near Mount Graham’s summit and invite a stand-replacing fire. In 1992, an ice storm and subsequent winds knocked down a large number of spruce trees and the resulting supply of dead timber provided a boost to the bark beetle population. From

1996 to 1998, an obscure moth caterpillar defoliated the spruce and fir around the telescopes. With the trees weakened by the caterpillar, the bark beetles did even more damage. By 1998, scientists recorded a new insect on the mountain, the spruce aphid, that had possibly gained a foothold because of global warming. The aphid thrived in the relatively dry, warm winters of 1998 through 2000, defoliating the spruce by sucking juice from their needles and making the trees even more vulnerable to the native spruce beetles, which kill their host by boring into the tree and laying eggs in cambium layer beneath the bark. Even without a warming climate, spruce beetles would have eventually attacked the forest atop Mount Graham – they are part of the natural cycle – but the spruce aphids may have accelerated the process. The onslaught of insects had profound

28

effects on the squirrel’s distribution atop Mount Graham. In 1996, there were 184 animals recorded in the spruce-fir habitat; five years later, UA biologists found fewer than 10.

As the squirrels retreated down the mountain into the transition zone and mixedconifer forest, they initially did just fine. By 1999, the total population was nearly 600 – triple the estimate prior to the telescope construction and the highest level ever recorded

(though part of the increase was due to more intensive surveys). UA astronomers didn’t claim their telescopes were responsible for the population increase, but a 10-year study of the observatories’ impact conducted by UA biologists did conclude in 2000 that the project had no negative effect on the subspecies – there was no difference in the behavior or reproductive success between the squirrels close to the scopes and those on other parts of the mountain. As it had for thousands of years, the squirrel population had waxed and waned with the crop of pine cones. So when the spruce aphid began to spread into the transition zone starting in 1999 and other trees produced fewer cones due to the drought, the squirrel population began to fall. By 2002, the overall population was down to about

300, about the level when the subspecies was listed 16 years earlier.

As precipitation disappeared from the Southwest in 2002 and the drought spurred both the Rodeo-Chediski Fire on the Mogollon Rim and the Bullock Fire on Mount

Lemmon, UA astronomers grew increasingly concerned about what would happen when major blaze began on Mount Graham. An inferno could fulfill the prophecy emblazoned on an Earth First! bumper sticker: “Nature bats last.” Given the history of sabotage on the mountain, an activist might even load up the bases for Mother Nature by setting fire to the forest. A hint of the danger had come in April 1996, when the human-caused 6,716acre Clark Peak Fire burned within 200 yards of the two smaller telescopes [I recollect, from discussions with an astronomer colleague who helped battle that fire, that it came

MUCH closer to the Vatican Observatory. I observed with the Vatican telescope a couple months before the fire.] that had already been built. It took 1,200 firefighters and

$7.9 million to stop a blaze that generated 250-foot flames. The Forest Service estimated

29

at least 27 squirrels died during the fire, with a minimum of 15 killed by the suppression tactics.

Six years later, as the 2002 Rodeo-Chediski Fire was winding down, Forest

Service crews quietly began to prune trees and remove “down-and-dead” wood some 200 feet out from Mount Graham’s telescopes. Some environmentalists complained, others said that if that’s all the UA was doing they didn’t care. By May 2004, when I hiked down Ash Creek Trail and went on the squirrel survey, the UA had done more than clean up the forest floor and trim low-hanging limbs near its telescopes. Crews had removed

850 dead trees 100 feet out from the buildings and UA now wanted to extend that work another 100 feet. The plan was based on advice from the Forest Service’s Jack Cohen, the expert on defending structures from wildfires who had concluded many of

Summerhaven’s cabins had burned because their owners hadn’t removed fuel from around the buildings. The 13-story steel and concrete building that houses the LBT is a formidable shield and is built to withstand 150 mph winds, but Cohen said that without clearing fuel 200 feet from the building’s perimeter, the equipment inside might be damaged by heat. “When you get something sticking up in the air 130 to 150 feet, 200 feet away is not that huge,” he said. On its own, the UA could install double-paned windows in the telescope building and screens on the air intakes to defend against embers. But to thin 100 feet deeper into the squirrel refugium, where neither telescope workers nor the public were allowed, UA needed the Forest Service’s blessing. Even though there were no active squirrel middens where UA wanted to thin – the squirrels had fled the area around the telescope years ago when the spruce-fir forest was wiped out by bugs – the Forest Service wouldn’t grant approval without extensive studies.

Environmentalists vowed they would fight the plan. The attitude seemed to be: UA made its bed, now it was time to sleep in it.

The additional thinning hadn’t been completed by June 22, 2004, when the first hint of monsoon moisture had arrived in Southern Arizona. As the sun baked the desert and gave rise to convection currents, water vapor boiled up into the sky like steam rising from a griddle sprayed with water. Thunderheads that resembled cauliflower florets

30

billowed several miles into the sky above Mount Graham and the other sky islands. The drops grew fat enough to overcome the updrafts and fell to earth, but most evaporated before reaching the ground, creating wispy curtains of almost-rain known as virga.

Within the cumulonimbus clouds, the rising and falling air generated friction, then forks of lightning that stabbed at Mount Graham and the other ranges. One bolt sparked a fire on Graham’s thickly vegetated north slope, about five miles east of where I’d hiked in

Ash Creek Canyon a month before and about six miles from the telescopes. The Gibson

Fire, named for the canyon in which it began, smoldered for a few days as relatively light winds and elevated humidity kept the flames in check. Forest Service officials didn’t even publicize the fire’s start and at times the blaze didn’t even put up any smoke. Four days after the Gibson Fire began, another lighting bolt started a fire in Nuttall Canyon, about fives miles to the west of the Ash Creek Trail and also about six miles from the scopes. Two days later, with rain occasionally falling, the Nuttall Fire was still only 150 acres. When photographer David Sanders and I went up the mountain to cover the story, we didn’t even know about the Gibson Fire and firefighters were so relaxed they played horseshoes in a lakeside campground. Both fires were in such steep, rugged terrain that fire crews couldn’t attack them directly to dig fuel breaks around their perimeter and instead relied on helicopters to drop water and flame retardant. Observatory officials kept an eye on the smoke, but business proceeded as usual atop the mountain.

Everything changed on July 2 with the resurgence of hot, dry, windy weather.

Both the Nuttall and Gibson fires roared to life and 11 firefighters nearly died. With burning embers raining down upon them, the members of two elite “hotshot” crews deployed their fire shelters – which look like silver pup tents when unfolded – and hid beneath the heat shields for 15 minutes. The shelters’ limited effectiveness in saving people caught in firestorms has earned them the nickname “shake and bakes,” but none of the firefighters was injured. As observatory workers fled the telescopes that evening, they turned on sprinklers outside, hoping the artificial rain would temper the flames’ inevitable charge toward the scopes. Federal officials assigned Dan Oltrogge’s management team to the blaze, along with 10 more hot shot crews.

31

On Independence Day, I flew over the mountain with David Sanders. Our Cessna circled around a column of milky white smoke that occasionally became dirty grey, even jet black, as the fires – now merging to cover more than 12,000 acres – churned through heavy timber. From the air it was clear that nothing could stop the flames from ascending toward the telescopes and the red squirrel’s home. Two military C-130 tankers swooped down to nearly skim the treetops and the LBT as they extended a belt of rust-colored flame retardant along the mountain’s crest. Once on the ground in Tucson, where it was

103 degrees, I called Swetnam, the tree-ring researcher. “It’s the one we’ve all been watching and waiting for,” he said. Koprowski, head of the squirrel monitoring project, told me “it’s what all of us connected to the biology end of this have feared.” Oltrogge conceded there was little the 805 firefighters under his command could do. “The only thing that will put this fire out,” he said, “is the weather and the lack of fuel as it moves down into the desert.” Privately, longtime telescope foes said they were rooting for the fire to overtake the scopes. Apache activists claimed the lightning bolts were divinely inspired. “We believe that this fire was not accidental, but a warning that the mountain can defend itself,” said Raleigh Thompson, a former tribal council member. “One of our

32 sacred songs mentions that the end of the world, of the universe itself, will be in fire, which will consume everything. This mountain was quiet until they began disturbing it to build the telescopes.”

Over the next two days, the Nuttall and Gibson fires doubled in size, became known as the Nuttall Complex and edged ever closer to the $200 million telescope complex. Firefighters thinned trees beside the state highway that runs along the spine of the mountain, then set intentional burns to rob fuel from the wildfires so they wouldn’t cross over the crest and scorch Graham’s southern face. Some of the best forest for the squirrels was situated in between the highway and the blazes, but firefighters had no choice: it was either burn that acreage intentionally or risk losing even more of the squirrel’s habitat.

At the telescope complex, as fire crews braced for an inferno that was 319 years in the making, they cut down 1,000 to 1,500 trees around the congressionally designated

32

nine-acre footprint, completing in a few days the thinning proposal many environmentalists vowed to fight for months, if not years. “If anything, they've done a little bit more than we would have,’ a Steward Observatory official told me. Even on the one of the nation’s most heavily litigated patches of land, the ESA would not stand in the way of emergency firefighting measures, nor does the act hinder other suppression efforts around the country. Fish and Wildlife may do an emergency consultation while a fire is in progress, but firefighter safety and protection of property take precedence.

The Nuttall Complex was spreading from treetop to treetop in a seemingly unstoppable crown fire on the evening of July 6. When it reached the area around the telescopes that had been thinned, the flames reportedly dropped to the ground. Jack

Cohen, the Forest Service expert on fireproofing structures, said that if the trees had not been removed, the inferno would have come within 50 feet of the LBT and “would very likely have caused at least some external damage.” Naturally, activists who’d fought the telescopes for two decades argued that the suppression tactics had further imperiled the squirrel. “This once again proves the university was wrong when they said the telescopes wouldn't harm the squirrels,” said Scotty Johnson, a longtime scope opponent who now worked for Defenders of Wildlife.

Based on my review of the fire maps and discussions with both firefighters and biologists, I believe that the telescopes’ presence atop Mount Graham actually would up helping the squirrel’s cause. The Nuttall Complex was burning at the peak of the region’s wildfire season, when incident commanders were competing for helicopters, hotshot crews and other firefighting resources. For several days, the Nuttall Complex was deemed one of the nation’s top priority fires and allocated more than 1,000 personnel, even the first air tankers in the country to be recertified for flying after the nation’s entire fleet was grounded over safety concerns. It was the telescopes atop Mount Graham, plus dozens of cabins, that added urgency to the suppression effort, not the squirrels. In their effort to defend the scopes, fire crews wound up protecting hundreds, if not thousands of acres of squirrel habitat.

33

By July 7, the scopes had been saved, but Ash Creek Canyon, one of my favorite spots on earth and one of the red squirrel’s strongholds, lay right between the Nuttall and

Gibson fires. For several days I watched anxiously as the blazes grew closer and closer on the north face of Mount Graham. Miraculously, monsoon rains arrived just as flames were licking at the upper reaches of the canyon. When the final maps were drawn for the